Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

Executive Summary

- Thirty states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) allow a broad category of tax subsidies known as itemized deductions. In most of these states, taxpayers can use these deductions to reduce their taxable income. Only two states structure these policies as tax credits that directly reduce tax liability. (For brevity, both types of policies will be referred to as “itemized deductions” in this report.)

- Every state offering itemized deductions allows deductions for mortgage interest and charitable gifts and most also allow deductions for property taxes and extraordinary medical expenses. Far fewer states allow deductions for sales or income taxes paid. Most states also offer their own varying menus of lesser-used deductions, such as those made available for gambling losses, investment interest, or losses resulting from natural disasters.

- State itemized deductions are typically based on federal tax law. Recent changes to federal law in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) have reshaped state itemized deductions by shrinking them in some ways and expanding them in others. For example, 19 states offering a property tax deduction conformed to new federal limitations on that deduction while 26 states and D.C. conformed to tighter limits on the mortgage interest deduction. On the other hand, 20 states recently lost a long-standing limit on the deductions claimed by high-income earners because they chose to remain coupled to the TCJA’s repeal of the “Pease” phase-down. In the wake of Pease’s demise, 18 states—a majority of those offering itemized deductions—now fail to apply broad limits to the itemized deductions claimed by high-income taxpayers. As recently as 2017, only two states had lacked such a limitation.

- Itemized deductions are regressive. These policies offer the largest benefits to higher-income taxpayers and little if any benefit to low- and middle-income families. Homeowners also tend to gain more from these deductions than renters because mortgage interest and property taxes are two of the largest deductions.

- Black and Hispanic families tend to receive smaller tax cuts from itemized deductions than White families. On average, households of color have lower incomes and lower homeownership rates than White households due to historic and current inequities in access to education and capita. This makes these groups less likely to itemize and more likely to claim smaller deductions even when they are able to itemize.

- State itemized deductions are often touted as tools for incentivizing certain behaviors, such as giving to charity or purchasing a home. But design flaws, combined with the inherent limits of using state tax policy to shape behavior, conspire to make these deductions ineffective means of achieving these goals.

- State lawmakers wishing to rein in itemized deductions have many options including outright repeal, applying broad-based phase-outs or caps, and limiting specific deductions such as for mortgage interest on second homes or for charitable gifts constituting a small percentage of income. This report discusses these options and identifies the states in which each could be enacted.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

Introduction

Thirty states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) allow a broad category of tax subsidies known as itemized deductions. These include tax preferences for charitable gifts, home mortgage interest, medical expenses, certain state and local taxes paid, and various other expenses. Typically, these subsidies take the form of a deduction that reduces taxable income but two states (Utah and Wisconsin) offer an itemized deduction credit instead that directly reduces tax liability. For brevity, this report will often use the term “itemized deductions” to refer both to traditional deductions and itemized deduction credits.

Itemized deductions are defined by the choice they require: the taxpayer must choose between claiming a standard deduction amount specified in state law or claiming a package of itemized deductions instead.[1] Typically, higher-income taxpayers are more likely to opt for itemization while lower- and middle-income taxpayers tend to claim the standard deduction.

While a few states offer some tax subsidies that resemble itemized deductions (for example, property taxes are partly deductible in Indiana, as are medical expenses in Massachusetts), this report focuses on the states offering a larger package of itemized deductions.

State itemized deductions are generally patterned after federal law, though nearly every state makes significant changes to the menu of deductions available or the extent to which those deductions are allowed. This report summarizes the key details of each state’s itemized deduction policies and discusses various options for reforming those deductions with a focus on lessening their regressive impact and reducing their cost to state budgets.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

Who Claims Itemized Deductions?

Because state itemized deductions are patterned after federal law, federal tax return data can provide some insights into who is most likely to claim state itemized deductions. At both the federal level and in the states, taxpayers claiming itemized deductions tend to have much higher incomes than taxpayers claiming the standard deduction.

Figure 2 shows that just 5.7 percent of households with income under $100,000 claimed federal itemized deductions in Tax Year 2018.[2] Nearly half (49.7 percent) of filers with income over $200,000 claimed itemized deductions, by contrast. Among filers with income in excess of $1 million, more than seven in ten (71.1 percent) claimed itemized deductions.

Before a taxpayer receives any benefit from itemized deductions, they need to muster enough deductions to make itemization worthwhile relative to claiming the standard deduction. At the federal level, the standard deduction in Tax Year 2019 (the year for which most households are currently preparing to file their returns) is $12,200 for single taxpayers, $18,350 for heads of household, and $24,400 for married couples. This means that a single taxpayer would need to pay more than $12,200 per year in mortgage interest, deductible state and local taxes, charitable gifts, and other deductible expenses to make itemization worthwhile. For a married couple these expenses would need to exceed $24,400 annually. Most families’ household budgets do not allow for this magnitude of spending in these categories, and thus most families receive no benefit from itemization.

These data show that high-income taxpayers are far more likely than any other group to clear these hurdles and claim itemized deductions. This is partly because they are more likely to be homeowners (mortgage interest and property taxes are two of the largest itemized deductions) and partly because they have more disposable income with which to make charitable contributions and pay state income and sales taxes.

High-income itemizers also tend to claim much larger amounts of federal itemized deductions than other itemizers. Looking just at those households claiming itemized deductions, Figure 2 shows that in 2018 the average itemizer earning less than $100,000 per year claimed $28,362 in itemized deductions whereas the average itemizer earning above $200,000 claimed $44,957. Itemizing households earning over $1 million per year claimed an average itemized deduction amount of $130,870.

Taken together, these numbers make two things very clear. First, lower- and middle-income families are much less likely to itemize than high-income households. And second, even in the rare instances where ordinary families do itemize, the deductions they claim tend to be much smaller than the deductions claimed by upper-income itemizers.

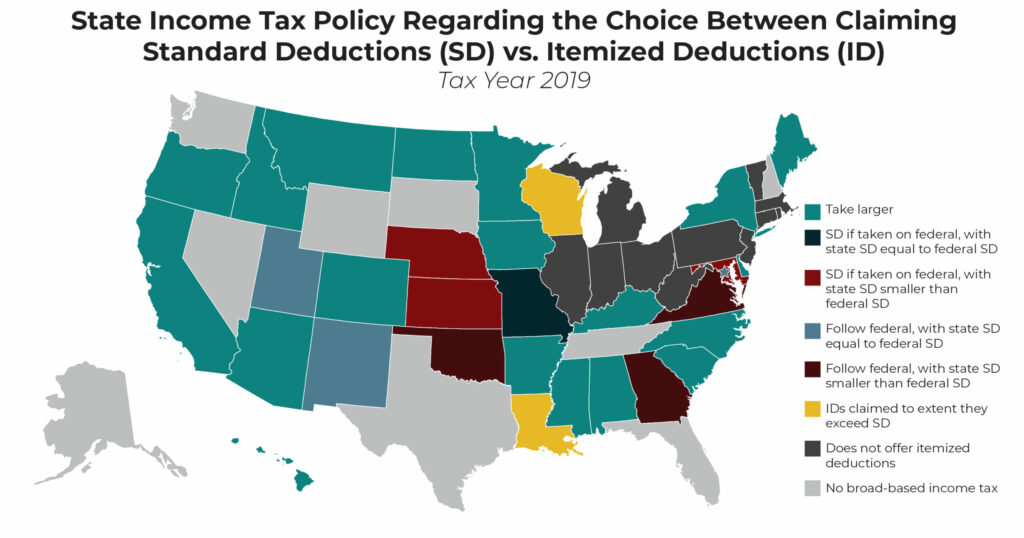

These general patterns hold true at the state level as well, though there are some important differences in the ways that states determine who will benefit from itemized deductions. States take one of four approaches in setting up the choice between claiming standard or itemized deductions. Each of these approaches results in slightly different itemization patterns:

- Take larger. The taxpayer compares their potential state standard deduction to their potential state itemized deductions and claims whichever results in a lower tax bill. This is the same type of process that taxpayers use when deciding whether to itemize on their federal returns. In states where the state standard deduction is lower than the federal standard deduction, this structure will tend to lead to more itemizers at the state level than at the federal level. On the other hand, many states offer a menu of itemized deductions that is somewhat less generous than the federal menu (denying the deduction for state income taxes paid is common, for example) and that can make it somewhat more difficult for taxpayers to muster enough itemized deductions to make itemization on their state returns worthwhile.

- Standard deduction if taken on federal. In these states, taxpayers who itemize on their federal returns can choose whether to itemize or claim the standard deduction on their state forms.[3] Taxpayers who claim the standard deduction on their federal forms, by contrast, are required to also do so on their state forms even when the state standard deduction is lower than the federal amount (which is usually, but not always, the case). While this arrangement has been in place for many years, its significance was recently amplified by the TCJA which significantly increased the federal standard deduction. In states using this approach, many of the taxpayers newly claiming the federal standard deduction because of the TCJA are finding that they must now claim the state standard deduction even though itemizing would have resulted in a lower state tax bill.[4] Generally speaking, these states should see itemization patterns similar to those occurring under federal law as the large federal standard deduction puts itemization out of reach for the vast majority of middle-income households.

- Follow federal. Some states require taxpayers to make the same decision on their state forms that they made on their federal forms. Federal standard deduction claimants must claim the state standard deduction and federal itemizers must itemize on their state forms as well. These states will see itemization patterns identical to those observed in federal law, under which high-income taxpayers are far more likely to itemize than other groups.

- Itemized deductions claimed to the extent they exceed standard deduction. Two states use different versions of this structure. In Louisiana, there is no state standard deduction, but taxpayers may claim state itemized deductions equal to the amount by which their federal itemized deductions exceed the federal standard deduction. The result is that federal itemizers receive (pared back) state itemized deductions in Louisiana, while federal standard deduction claimants receive no state deduction at all. In Wisconsin, any taxpayer earning under $106,000 (single) or $124,279 (married) can claim a state standard deduction. Taxpayers choosing to also claim the state’s itemized deduction credit, however, must subtract the state standard deduction they received from their itemization-eligible expenses in order to avoid receiving two tax subsidies on the same expense. Upper-income Wisconsin residents receive no state standard deduction and can therefore claim all their eligible expenses under the state’s itemized deduction credit.

Figure 4 provides an overview of the states taking each of these four broad approaches. The most common approach, used in 19 states, is to allow taxpayers to claim whichever deduction affords them the larger tax cut.

Four states require taxpayers to claim the standard deduction if they did so in their federal forms. This requirement is more consequential in Kansas, Maryland, and Nebraska than it is in Missouri because the first three states listed offer standard deductions that are significantly smaller than the federal standard deduction. In these states, taxpayers can find themselves being forced to claim the standard deduction on their state forms even though itemization would have resulted in a lower state tax bill.

FIGURE 4

Note: North Dakota’s forms appear to require that the taxpayer claim the type of deduction at the state level that they claimed at the federal level, but since North Dakota’s package of itemized deductions is identical to the federal package, in practice this functions as a “take larger” choice.

Note: North Dakota’s forms appear to require that the taxpayer claim the type of deduction at the state level that they claimed at the federal level, but since North Dakota’s package of itemized deductions is identical to the federal package, in practice this functions as a “take larger” choice.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

Five states and D.C. require taxpayers to claim the same type of deduction they claimed on their federal forms. This is most significant in Georgia, Oklahoma, and Virginia because these states offer smaller standard deductions than the federal government. New Mexico and D.C., by contrast, offer standard deductions equal to the federal amount and thus most taxpayers would choose to make the same itemization decision on their federal and state forms even if they were not required to do so.[5] In Utah, taxpayers receive a state itemized deduction credit calculated based on either the standard deduction they claimed on their federal forms, or the federal itemized deductions they claimed less the deduction for state and local income taxes.

Finally, two states use the more unusual choice structure described above where only eligible expenses in excess of either the federal standard deduction (in Louisiana) or the state standard deduction (in Wisconsin) can be claimed as an itemized deduction.

Broadly speaking, the details of state law are important in determining precisely who will claim itemized deductions and how much they will claim. The details vary but the clear overall pattern is that higher-income households are much more likely to itemize than other families and are likely to claim much larger amounts of itemized deductions when they do itemize.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions

The previous section offered a glimpse into the distributional impact of itemized deductions using federal tax return data. While a full revenue and distributional analysis of every state’s itemized deduction policies is beyond the scope of this report, the following discussion and data further illustrate those effects by looking at the impact of current policy in Maryland, a state that offers a fairly typical package of itemized deductions linked to federal rules.

Maryland follows most other states in disallowing the deduction for state or local income taxes paid. Because of its linkage to federal law, Maryland caps its own state and local tax (SALT) deductions for property and sales taxes paid at $10,000 per year. Similar to the federal government and most states, Maryland does not apply a phase-down or other broad-based limit to its itemized deductions.

Taxpayers claiming the standard deduction on their federal tax forms must also do so on their Maryland tax forms (that is, Maryland falls into the second group of states described in the previous section). Maryland’s standard deduction (ranging from $1,500 to $4,500 depending on filing status and income level) is much lower than the federal amount (ranging from $12,200 to $24,400). Because of this, many Maryland taxpayers who are required to claim the state standard deduction would have seen a lower state tax bill if they had been allowed to itemize on their state tax forms. Limiting state itemized deductions to only those taxpayers who itemize on their federal forms skews the benefits of state itemization even more heavily in favor of high-income earners than would otherwise be the case, as high-income taxpayers are more likely to itemize on their federal forms than any other income group.

Using the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model, we estimate that roughly one in four Maryland taxpayers will claim state itemized deductions in Tax Year 2019 while the other three will claim the standard deduction. Among the bottom 80 percent of households, just 16 percent will itemize on their state returns.[6] Among the top 5 percent of Maryland households, by contrast, 70 percent are expected to itemize on their state tax forms.

We estimate that itemized deductions will reduce Maryland’s state personal income tax collections from Maryland residents by $869 million in Tax Year 2019.[7] This amounts to a roughly 8 percent reduction in state personal income tax revenue. While the analysis contained in this section focuses on state tax impacts, it is important to note that itemized deductions also drain hundreds of millions of dollars from local coffers because Maryland’s local income taxes are applied to the state’s definition of taxable income after itemized deductions are subtracted.

Figure 5 shows that more than two-thirds (69 percent) of the state tax cuts associated with itemization in Maryland flow to the top 20 percent of earners, a group composed of households earning at least $135,000 per year. Expressed as a percentage of income, the average tax cut (0.39 percent) is largest for households earning between $135,000 and $278,000. In raw dollars, the largest average tax cuts ($4,257 per household) go to the top 1 percent of earners, a group composed entirely of households earning more than $613,000 per year. The maximum state tax cut provided by the standard deduction, by contrast, stands at $259 per year.[8]

Expressed as a percentage of income, the distribution of Maryland’s itemized deductions is regressive throughout the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution and therefore exacerbates the regressivity of the state’s overall system.[9]

The lopsided distribution of Maryland’s itemized deductions also leads to starkly different impacts by race and ethnicity.[10] Figure 6 shows that while 56 percent of households in Maryland are headed by White individuals, this group receives an outsized 69 percent of the tax cuts associated with state itemized deductions. Among this group, the benefits are overwhelmingly geared toward higher-income earners. White households earning over $135,000 per year receive half (50 percent) of the benefits of state itemization, despite composing just 14 percent of households in Maryland.

Asian households also receive outsized benefits, getting 6 percent of the benefits of itemization despite composing just 5 percent of households. Meanwhile, Black households make up 30 percent of all households in the state but receive just 20 percent of the tax cuts associated with itemization. Similarly, Hispanic households represent 6 percent of all households but receive just 4 percent of the benefits of itemization.

Historic and current inequities in access to education and capital have caused Black and Hispanic households to have lower incomes and lower rates of homeownership than White households, on average. Both these outcomes negatively affect these groups’ ability to make use of itemized deductions.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

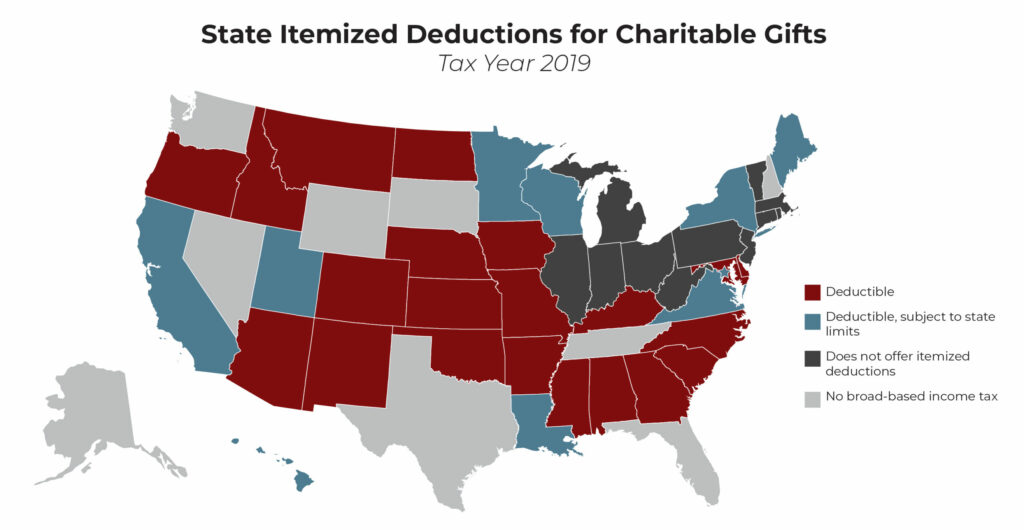

Charitable Gifts Deductions

Every state allowing itemized deductions (30 and D.C.) allows a deduction for charitable gifts. Broad tax subsidies for all types of charitable giving are rare outside of these states although Vermont, which recently eliminated itemized deductions, does allow a 5 percent credit on up to $20,000 in charitable gifts per year. Higher-percentage tax credits are also offered in many states for donations to specific causes selected by lawmakers for special treatment: most often private K-12 school vouchers, conservation easement donations, and community development funds.[11]

Itemized deductions for charitable gifts are often touted as encouraging philanthropy and its attendant societal benefits. But it is doubtful that state deductions are succeeding in this regard. Because state tax rates are relatively low, the incentive effect of offering a deduction from state taxable income is modest. The average top income tax rate among states offering itemized deductions is just 6.7 percent, meaning that a state itemized deduction will typically provide just one dollar in tax cuts for every 15 dollars donated. Most state charitable deductions are undoubtedly claimed for donations that would have occurred even if these state deductions were not offered. These windfall benefits undercut the efficiency of state charitable deductions as tools for spurring philanthropic behavior.

Another troubling reality of charitable gift deductions is that they are usually put out of reach for middle-class families, as those families are unlikely to claim itemized deductions.[12] High-income families, by contrast, can access the charitable deduction by donating even just a very small fraction of their earnings to charity. As a result, state charitable deductions offer a partial state match on donations to causes favored by high-income households but not to the causes that families with more modest incomes deem to be important. This also leads to troubling differences in the treatment of donations made by households headed by people of different races and ethnicities, as Black and Hispanic households are far less likely than White or Asian ones to earn enough income to itemize and qualify for a tax subsidy on their charitable gifts.

FIGURE 7

Notes: Charitable deductions are typically limited to 50 or 60 percent of the taxpayer’s income, but these limitations are not described above. Instead, “state limits” refers to the provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs. Note that some states offer tax benefits for charitable giving in the form of something other than an itemized deduction. Vermont, for example, offers a tax credit equal to 5 percent of the first $20,000 donated to charity.

Notes: Charitable deductions are typically limited to 50 or 60 percent of the taxpayer’s income, but these limitations are not described above. Instead, “state limits” refers to the provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs. Note that some states offer tax benefits for charitable giving in the form of something other than an itemized deduction. Vermont, for example, offers a tax credit equal to 5 percent of the first $20,000 donated to charity.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

The good news is that states that wish to continue offering an itemized deduction in return for charitable gifts have options for lessening this unfairness. Much of the bias toward high-income families built into the charitable deduction is related to the fact that the main hurdle to accessing the deduction is a flat-dollar standard deduction. That hurdle can be cleared much more easily by high-income families than by lower- or middle-income families. Figure 8 illustrates that a married couple earning $5 million annually, for instance, can claim the charitable deduction even if they donate just a tiny fraction—one half of one percent—of their earnings to charity. A middle-class couple, by contrast, may not see their charitable gifts matched with a state charitable deduction even if they are twenty times as generous and donate 10 percent, or more, of their earnings to charity.

Some of this unfairness could be addressed by reforming charitable deductions to include a floor that varies based on taxpayer income level. By mandating that only charitable gifts above 5 percent of income are deductible, for instance, states could put middle-class and upper-income families on a more even footing. Families of both types would need to make a financial sacrifice that is meaningful, relative to their income, before the charitable deduction potentially becomes available.[13]

Such an approach may also improve the efficiency of the deduction as a tool for shaping behavior, as smaller gifts that were likely to occur even without the deduction would no longer be subsidized.

And this approach could also rein in the deduction’s cost, freeing up room in state budgets to invest in other essentials.

While no state uses this type of floor in its charitable deduction calculations today, nearly every state uses a floor in administering its medical expense deduction (discussed later in this report). Moreover, states impose a variety of other limits on the charitable deduction (such as caps on the maximum deduction claimed and phase-downs or phase-outs of the deduction for high-income earners) that also lessen the deduction’s tilt toward upper-income families. Those limits are described later in this report.

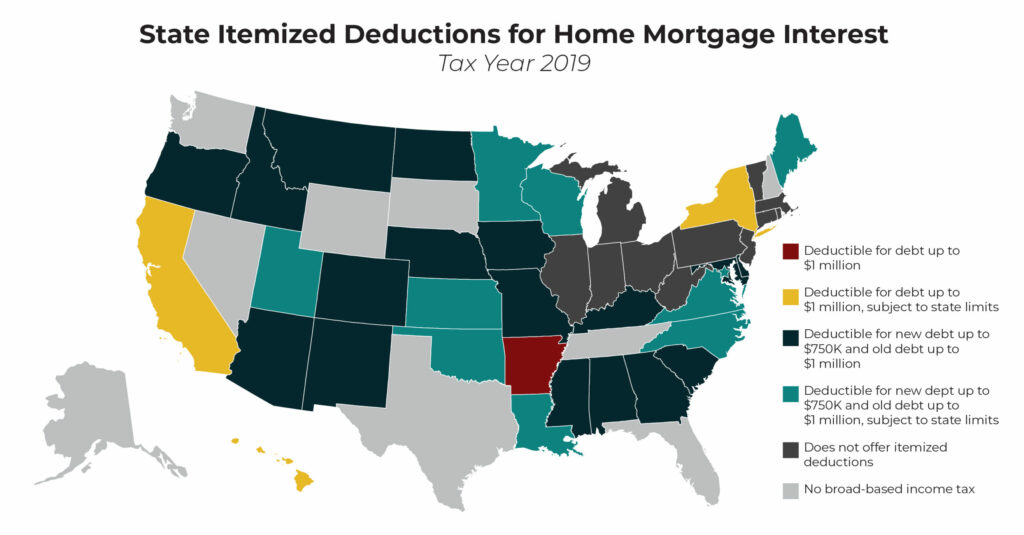

Home Mortgage Interest Deductions

Every state allowing itemized deductions (30 and D.C.) allows a partial deduction for home mortgage interest. In four of these states (Arkansas, California, Hawaii, and New York), the deduction is available on mortgage debt of up to $1 million. In the remaining 26 states and D.C., that debt limit is reduced to $750,000 for debt incurred after December 14, 2017. This reduced limit was inherited from recent changes to federal law contained in the TCJA.

The home mortgage interest deduction has long been touted as a tool for boosting homeownership rates and the societal benefits (financial security, healthier neighborhoods, etc.) that are claimed to flow from a higher rate of homeownership. But there is no clear economic evidence that the mortgage interest deduction is succeeding in accomplishing these goals. Indeed, some studies have suggested that the deduction might reduce homeownership by driving up housing prices.[14] Higher housing prices make the most significant barrier to homeownership—the initial down payment—even more daunting.

FIGURE 9

Notes: Generally, mortgage debt up to $1 million is eligible for the deduction if the debt was incurred before Dec. 15, 2017. The federal government and most states have reduced that threshold to $750,000 for debt incurred after that date. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs.

Notes: Generally, mortgage debt up to $1 million is eligible for the deduction if the debt was incurred before Dec. 15, 2017. The federal government and most states have reduced that threshold to $750,000 for debt incurred after that date. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

While the TCJA technically left the home mortgage interest deduction intact, it put the federal deduction out of reach for most families who previously claimed it by making itemization less attractive.[15] That is, by doubling the standard deduction and capping the state and local tax (SALT) deduction at $10,000, the TCJA caused far fewer families to itemize and eliminated the incentive effect of the federal mortgage interest deduction for most families—especially those in the middle of the income distribution. Less than four percent of families earning under $100,000 in 2018 benefited from the federal mortgage interest deduction, and one in five (21.4 percent) families earning between $100,000 and $200,000 benefited.[16]

Interestingly, this de facto repeal of the federal deduction for most middle-class families does not seem to be deterring home buyers.[17] And if the federal mortgage interest deduction has an unclear relationship to homeownership, as the post-TCJA experience of the housing market thus far suggests, then smaller state tax deductions are also likely to do far less than their proponents claim.

For context, a family buying a $300,000 home and facing a 7 percent state income tax rate could expect to save no more than $63 per month during their first year of homeownership from a state mortgage interest deduction—an amount that will rarely be enough to tip the scales in favor of owning instead of renting. In reality, the savings could be significantly lower than this amount even in the first year for a middle-income family and will decline over time as the interest is paid off.[18]

In almost all cases, a state home mortgage interest deduction serves as a subsidy to taxpayers who would have owned their homes even in the absence of such a deduction. Because of this, the deduction tends to offer little benefit to moderate-income families unable to afford homeownership. It also offers undersized benefits to people of color, who are less likely than White families to own a home even after controlling for differences in income.[19] A long history of racist housing policies, including restricting Black home buyers to deliberately devalued neighborhoods through redlining, has depressed the ability of communities of color to acquire wealth and achieve homeownership.[20]

Moreover, some aspects of the mortgage interest deduction have no connection at all to the goal of boosting homeownership rates. For instance, the federal deduction and every state deduction are available not just for principal residences, but for vacation homes as well (mortgage interest on rental properties is typically deductible as a business expense under a separate section of the law). Wisconsin is the only state that partly reins in the deduction available for vacation homes, denying it for second homes purchased outside the state.[21] Lawmakers in Oregon have contemplated a somewhat broader measure that would deny the deduction for all second homes—a change that the Legislative Revenue Office estimates would raise $5 million in state income tax revenue per year.[22]

Given the regressivity and ineffectiveness of the mortgage interest deduction, outright repeal is an appealing policy option. For states that wish to retain the deduction but want to focus its impact more squarely on people trying to achieve homeownership, limiting the deduction only to primary residences and reducing the deductible debt limit to $750,000 or less are logical places to start.

Additionally, states could consider capping the amount of mortgage interest that taxpayers can deduct. For example, Oklahoma and North Carolina apply caps of $17,000 and $20,000, respectively, to the combined amount of mortgage interest and property tax that can be deducted each year.

Medical Expense Deductions

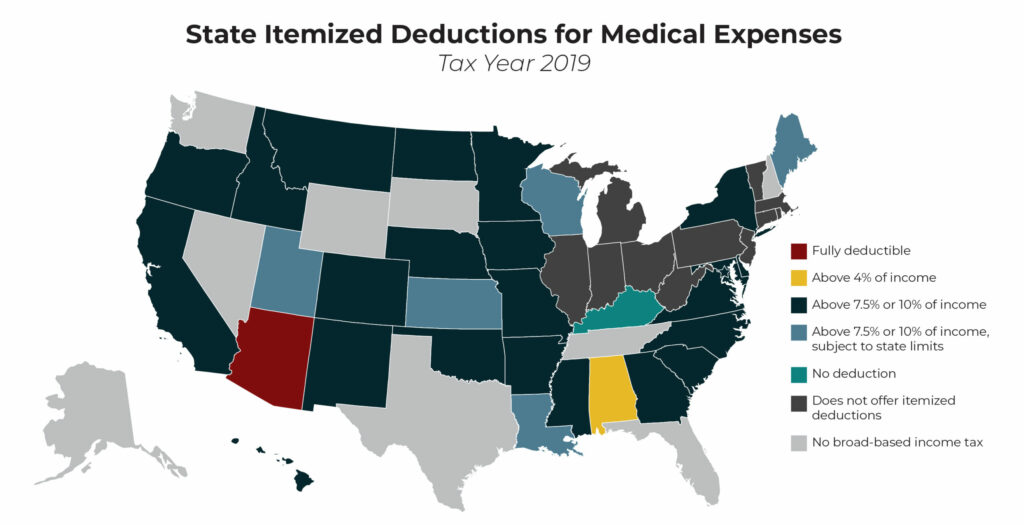

Twenty-nine states and D.C. allow an itemized deduction for certain medical expenses. Kentucky is the only state that allows for itemization but specifically denies the deduction for medical expenses. In some states, such as Massachusetts and New Jersey, partial deductions for medical expenses are allowed even though itemization is unavailable. In New Mexico, a supplementary medical expense deduction is available beyond the state’s ordinary itemized deduction.

Except for Arizona, every state allowing a medical expense deduction imposes a floor on the deductible amount, meaning that only amounts in excess of a specific percentage of income can be deducted. These floors are intended to limit the deduction to people facing extraordinary medical expenses that create genuine financial hardship. Alabama uses a 4 percent floor while every other state uses a floor of either 7.5 or 10 percent.

The federal floor was scheduled to rise from 7.5 to 10 percent starting in Tax Year 2019, but legislation enacted in December 2019 delayed that increase until Tax Year 2021. As a result of their linkages to federal tax law, most states with medical expense deductions have seen their own floors remain at 7.5 percent for the time being. Figure 10 does not distinguish between the states with 7.5 versus 10 percent floors because, as of this writing, some states are still updating their tax forms and others are debating whether to retroactively conform to the federal change. Additional information on state medical expense deduction floors is available in Appendix A.

FIGURE 10

Notes: This map combines the 7.5% and 10% percent categories because debates over the 2019 level are ongoing in some of these states. A more detailed summary of what appears on state tax forms as of this writing is available in Appendix A. The income floors used to determine the amount of expense eligible for a deduction are typically based on Federal Adjusted Gross Income (FAGI), except in the following states where they are based on a state-specific AGI definition instead: Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii, and Montana. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, including phase-outs in Maine and Utah, a credit in lieu of deduction in Wisconsin, Louisiana’s allowance only for itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction, and Kansas’s allowance for only 75 percent of expenses exceeding 10% of income. Note that some states also allow above-the-line deductions (not shown here) for medical expenses, including Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New Mexico.

Notes: This map combines the 7.5% and 10% percent categories because debates over the 2019 level are ongoing in some of these states. A more detailed summary of what appears on state tax forms as of this writing is available in Appendix A. The income floors used to determine the amount of expense eligible for a deduction are typically based on Federal Adjusted Gross Income (FAGI), except in the following states where they are based on a state-specific AGI definition instead: Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii, and Montana. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, including phase-outs in Maine and Utah, a credit in lieu of deduction in Wisconsin, Louisiana’s allowance only for itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction, and Kansas’s allowance for only 75 percent of expenses exceeding 10% of income. Note that some states also allow above-the-line deductions (not shown here) for medical expenses, including Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New Mexico.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

Taxpayers with potentially deductible medical expenses must clear two hurdles before those expenses trigger any state tax reduction: they need to muster enough itemized deductions overall to make itemization worthwhile while also paying medical expenses that exceed the income floor set by their state. Because of this, the medical expense deduction is not always available to taxpayers facing medical hardships. Moreover, because state tax rates tend to be low (top tax rates average 6.7 percent among the states offering itemized deductions), even taxpayers who claim the deduction will only see a small fraction of their medical expenses offset by these policies.

Relative to most itemized deductions, the distributional impact of the medical expense deduction is much less skewed toward higher-income earners. At the federal level, the medical expense deduction is the only major category of itemized deduction that middle-income earners are more likely to claim than high-income earners (see Appendix C).[23] It is also the only major itemized deduction for which most claimants (73 percent) earn under $100,000 per year. This is because high-income taxpayers are more likely to have high-quality health insurance and because the floor on deductible expenses makes the deduction less important as income rises (for a family with $1 million in income, for example, a 10 percent floor only allows deductions for expenses above $100,000 per year).

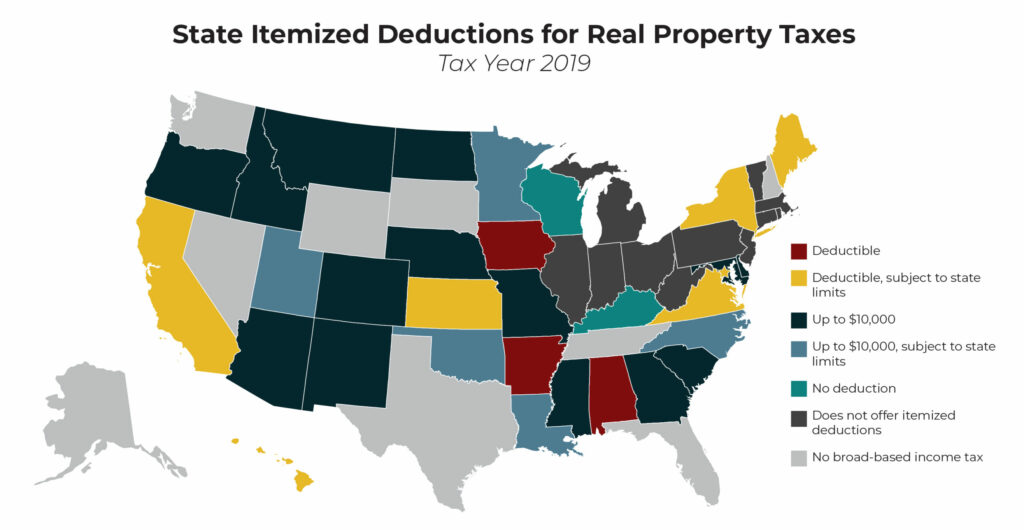

Real Property Tax Deductions

Twenty-eight states and D.C. allow an itemized deduction for real property taxes paid on taxpayers’ homes.[24] Kentucky and Wisconsin are the only states to allow itemization without offering a deduction (or credit, in Wisconsin’s case) for real property taxes.

Nineteen of the states offering a real property tax deduction now subject it to the same $10,000 cap that applies to state and local tax (SALT) deductions claimed at the federal level. Like at the federal level, the states with a $10,000 cap apply it to the full complement of SALT payments that the taxpayer chooses to deduct: real and personal property taxes, and sometimes sales or income taxes as well.

Only ten jurisdictions allow an itemized deduction for property taxes without applying the $10,000 cap (Alabama, Arkansas, California, DC, Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, New York, and Virginia), although most of these states apply other limitations to the deduction such as phase-outs for higher-income earners (see Figure 20 later in this report). Alabama, Arkansas, and Iowa are the only states that allow an uncapped real property tax deduction without any state limitation of this type.

While Indiana and New Jersey do not allow for itemization, both states offer their own partial deductions for real property tax payments to anyone who pays state personal income tax. Many states also offer tax credits of various types designed to partly offset property taxes paid.

FIGURE 11

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap usually applies to some combination of real property taxes, personal property taxes, income taxes, and/or sales taxes. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs. Note that while Indiana and New Jersey do not offer itemized deductions, they provide standalone property tax deductions for some taxpayers. Additionally, many states offer tax credits (not shown here) designed to partly offset property tax payments.

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap usually applies to some combination of real property taxes, personal property taxes, income taxes, and/or sales taxes. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs. Note that while Indiana and New Jersey do not offer itemized deductions, they provide standalone property tax deductions for some taxpayers. Additionally, many states offer tax credits (not shown here) designed to partly offset property tax payments.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

The two main rationales for offering an itemized deduction for real property taxes paid are to reduce the cost of property taxes for homeowners and to aid local governments in raising revenue. But these deductions are largely ineffective at achieving both these goals.

For lawmakers concerned with property tax affordability, itemized deductions are unappealing because they are not targeted toward the families most likely to have difficulty paying their property tax bills. Most families do not earn enough to itemize, meaning that the deduction is typically out of reach for homeowners with moderate incomes. Moreover, by structuring the subsidy as a deduction rather than a credit, the tax savings associated with each dollar of property tax deduction are often higher for upper-income families who find themselves in higher state tax brackets. And renters paying the property tax indirectly through their rent payments receive no benefit at all.

By contrast, an alternative state tax policy known as a “circuit breaker” tax credit can be tailored to ensure that property taxes do not exceed taxpayers’ ability to pay.[25] These credits work by steering tax cuts only to taxpayers facing property tax bills in excess of a specific percentage of their income. If property taxes grow too large relative to income, a circuit breaker credit can intervene to prevent a property tax overload. This can be particularly useful to people recently laid off from their job, living in a gentrifying area with rapidly increasing housing values, or who are retired and on a fixed income.

For states concerned about property tax affordability, eliminating or scaling back itemized deductions for real property tax payments can be a straightforward way to fund new or expanded circuit breaker credits, which tend to be much better targeted toward solving this problem.

Another rationale sometimes advanced in favor of state deductions for local property tax payments is that the deductions make it easier for localities to raise revenue. By allowing taxpayers to write off their local property taxes on their state tax forms, the state government is effectively paying a portion of each itemizer’s local property tax bill.

Since state tax rates tend to be low, however, the portion paid by the state is also low (a taxpayer facing a seven percent marginal state tax rate, for example, will see no more than seven percent of their property tax bill paid by the state).

More importantly, using this mechanism to provide aid to local governments tends to skew such aid in favor of wealthier communities that need it the least. Communities with higher incomes and property values tend to have more residents able to take advantage of itemization. Communities where residents tend to have more moderate incomes, including many communities where people of color are disproportionately likely to live, tend to see more of their residents claim the standard deduction and therefore see undersized benefits from state deductions for real property tax payments.

One of the most important goals that states should pursue in aiding local governments is ensuring that even those communities with sparse resources are able to provide a high-quality education to local children. Real property tax deductions do exactly the opposite by steering most aid into those areas that need it the least.

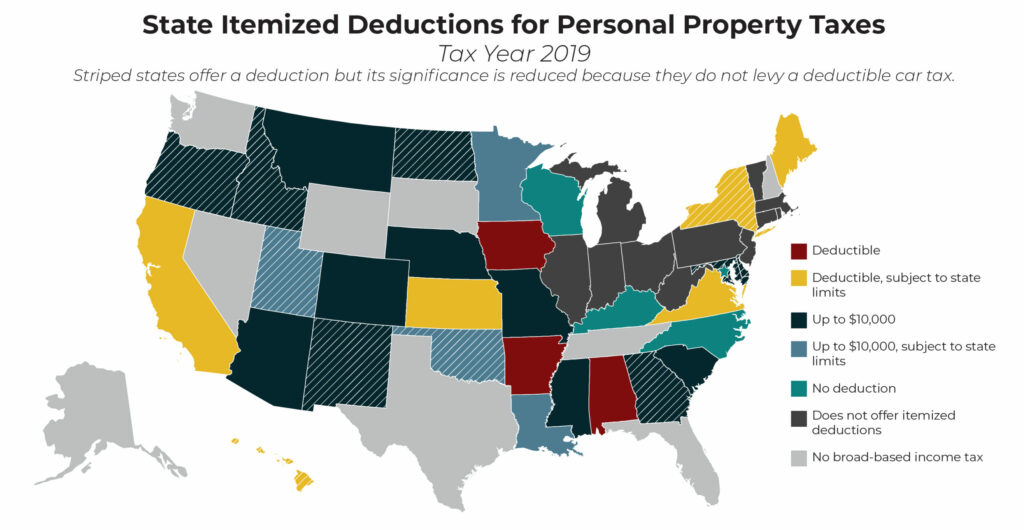

Personal Property Tax Deductions

Twenty-seven states allow itemized deductions for personal property tax payments. Alabama, Arkansas, and Iowa are the only states that allow such a deduction without subjecting it to the $10,000 SALT cap or any other broad-based limit such as a phase-out for taxpayers at higher incomes.

The most prominent type of personal property tax is levied on the value of motor vehicles (registration fees unrelated to a vehicle’s value are not considered to be personal property taxes). The average itemizer living in states levying motor vehicle property taxes deducted $392 in personal property taxes on their federal tax returns in 2017, compared to an average deduction of just $93 among itemizers living in states without such taxes.[26]

Aside from motor vehicles, other forms of personal property often subject to taxation include mobile homes and boats. Business personal property is also sometimes taxed, although these taxes are usually deducted as business expenses rather than as itemized deductions.

FIGURE 12

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap usually applies to some combination of real property taxes, personal property taxes, income taxes, and/or sales taxes. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs.

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap usually applies to some combination of real property taxes, personal property taxes, income taxes, and/or sales taxes. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, such as flat dollar caps and phase-outs.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

Deductions for motor vehicle taxes may be somewhat less regressive than deductions for real property since vehicles constitute a larger share of the net worth of lower- and moderate-income families. In practice, however, itemized deductions for personal property taxes provide little benefit to the families most likely to have difficulty affording their car taxes because those families are unlikely to earn enough income to claim itemized deductions and, even if they do itemize, will often find themselves in lower tax brackets where the tax savings from a deduction are lower than the savings flowing to high-income families.

Kentucky and North Carolina are the only states that levy a car tax, allow itemization, and yet specifically disallow the personal property deduction at the state level. Wisconsin and the District of Columbia also do not offer personal property tax deductions, though this choice is made less consequential by the fact that both these jurisdictions lack car taxes and the average itemizer therefore pays very little in personal property tax.[27]

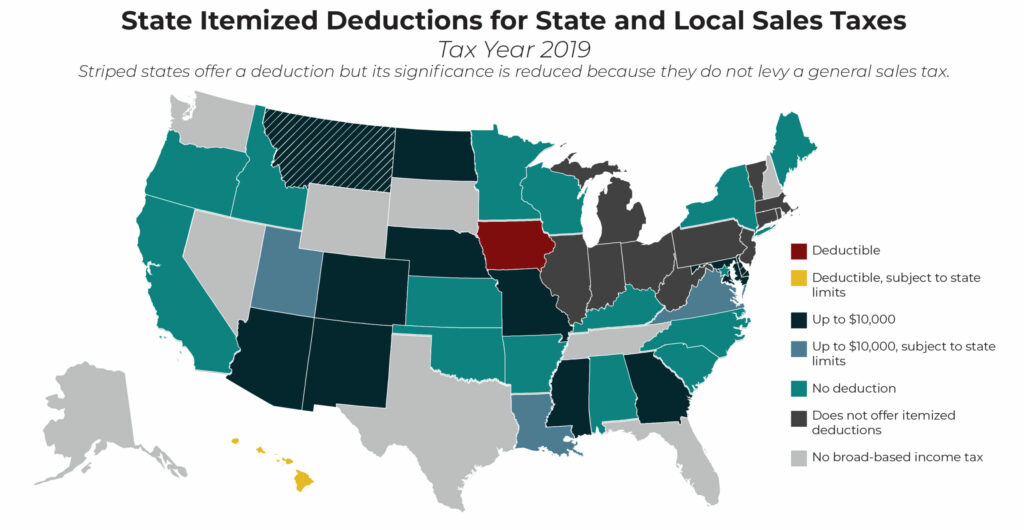

State and Local Sales Tax Deductions

Sixteen states allow taxpayers the option of deducting state and local general sales tax payments, as shown in Figure 13. All but two of these states (Iowa and Hawaii) subject the deduction to the $10,000 SALT cap, meaning that taxpayers may not deduct more than $10,000 in combined property and sales taxes per year.

FIGURE 13

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap applies to the taxpayer’s combined deduction of both sales and property taxes. “State limits” refers to the provisions described in Figure 20, including phase-downs or phase-outs in Hawaii, Utah, and Virginia, as well as Louisiana’s allowance only for itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction.

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap applies to the taxpayer’s combined deduction of both sales and property taxes. “State limits” refers to the provisions described in Figure 20, including phase-downs or phase-outs in Hawaii, Utah, and Virginia, as well as Louisiana’s allowance only for itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

At the federal level, the sales tax deduction has historically been used most frequently in states that lack personal income taxes (and therefore lack state itemized deductions as well) because taxpayers must choose between deducting either income or sales taxes—not both. For the upper-income households who tend to claim itemized deductions and who live in states with income taxes, their state and local income tax liability typically exceeds their state and local sales tax payments.

Nonetheless, the sales tax deduction is still used by some taxpayers in states with income taxes. In the sixteen states allowing this deduction, more than 1 million households claimed the deduction on their federal tax forms in Tax Year 2017, the most recent year for which IRS data are available.[28] While the recent increase in the federal standard deduction will likely cause this number to fall for 2018 and beyond, other factors will create some upward pressure on the use of this deduction.

Specifically, the interaction between federal and state itemization rules has created an increased incentive for some households to claim the sales tax deduction. To understand why, consider a hypothetical, high-income taxpayer living in Montgomery County, Maryland who pays $20,000 in state and local income taxes, $8,400 in property taxes, and $1,900 in deductible sales taxes each year.[29] Prior to implementation of the $10,000 SALT cap, this taxpayer would have deducted $28,400 on federal tax forms (income and property tax) but just $8,400 on state forms since Maryland does not allow a deduction for state and local income tax payments.

Under the new cap, however, this taxpayer will only be allowed to deduct $10,000 on federal and state tax forms and will now choose to meet that cap by deducting their entire property tax bill ($8,400) and most of their sales tax payments ($1,600). Since Maryland allows sales taxes—but not income taxes—to be deducted against taxpayers’ state income tax liability, the taxpayer’s deduction on state tax forms will rise to $10,000, compared to just $8,400 under the previous scenario. The result may be counterintuitive, but in this case capping the SALT deduction at $10,000 actually caused this taxpayer’s state-level SALT deduction to increase.

State lawmakers’ best course of action is to repeal the deduction for sales taxes outright, as about half the states offering itemized deductions have already done. At the federal level, the main purpose of the sales tax deduction is to provide aid to state and local governments, albeit in a crude way, as the deduction allows the federal government to essentially pay a portion of taxpayers’ sales tax liabilities. Because there is little point in a state paying taxes to itself, however, this rationale cannot be used to support state income tax deductions for state sales taxes paid. In other words, the deduction is largely pointless at the state level.

While states could decide to retain the sales tax deduction only for payments of local-level general sales taxes, it is hard to see any meaningful advantages to such a policy. A deduction for local sales tax payments could be viewed as a form of state aid to local governments, but the fact that most localities levy very low sales tax rates makes the deduction a weak tool for this job. Moreover, because almost nobody saves all receipts from purchases made throughout the year, it is impossible to administer the deduction with any precision. In most cases taxpayers do not deduct their actual sales tax payments to local governments, but rather a very rough estimate of those payments based on basic characteristics like income level and family size. In other words, taxpayers with similar incomes tend to receive similar sales tax deductions even when their consumption habits and local sales tax payments are drastically different.

States that are unwilling to repeal the sales tax deduction outright also have other options for chipping away at the deduction, such as subjecting it to the $10,000 SALT cap (which only Hawaii and Iowa currently fail to do) or applying broad-based itemized deduction limits to the deduction such as phase-outs or phase-downs.

Of all the states allowing a general sales tax deduction, repeal should be least controversial in Delaware and Montana. Despite their lack of general sales taxes, more than 1,500 taxpayers in each of these states deducted general sales taxes on their federal tax forms in 2017 and may have done so on their state forms as well. Presumably, many of these taxpayers were deducting general sales taxes they paid while living in, or visiting, other states during 2017.[30] There is no benefit to Delaware or Montana from offering a state tax deduction for such payments to other states.

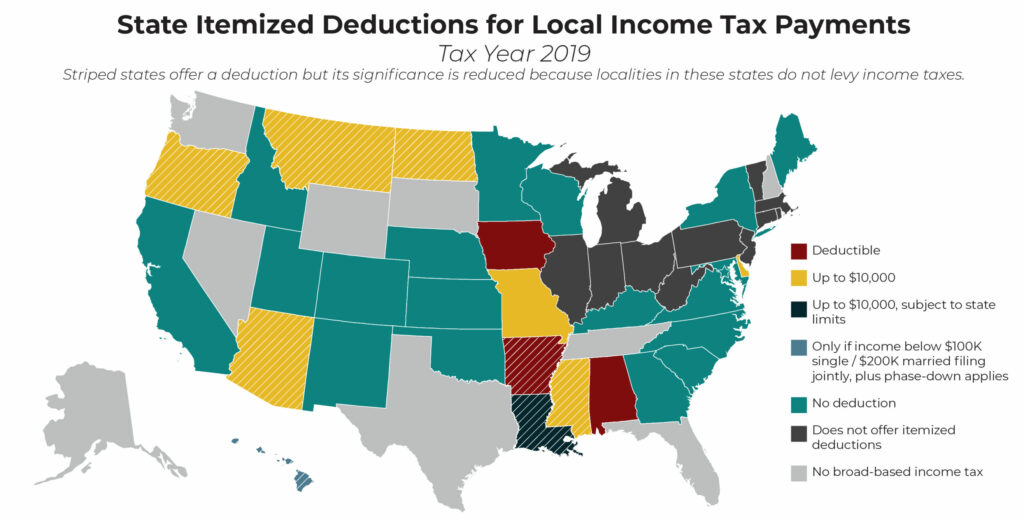

Local Income Tax Deductions

Twelve states allow a deduction for local income taxes paid, although only four of these states allow their localities to levy such taxes on individuals: Alabama, Delaware, Iowa, and Missouri. Among these states, Alabama and Iowa allow full deductions for such tax payments while in Delaware and Missouri the combined amount of property tax and local income tax deducted cannot exceed $10,000 per year.

State deductions for local income taxes paid can be viewed as a way of aiding local governments because the state forgoes an amount of income tax revenue in proportion to the amount of local tax paid by state residents. And such deductions are far easier to administer than deductions for local sales taxes paid since, unlike with sales taxes, residents can easily determine how much local income tax they paid each year.

But state deductions for local income tax payments are far from the ideal way to provide aid to local governments. Because states often prohibit many of their localities from levying income taxes, this subsidy often does not reach many areas within a state. Delaware, for example, only allows local income taxation in its largest city (Wilmington) while in Missouri, only St. Louis and Kansas City levy such taxes. The rural areas of these states are largely shut out of the benefits of these deductions.

Even in states such as Iowa where a broader group of localities levy income taxes, the benefits of this deduction tend to skew toward higher-income areas since these areas have residents who are more likely to earn enough income to claim state itemized deductions. Upper-income taxpayers also tend to derive more benefit from each dollar deducted since, under a graduated rate system, they tend to claim those deductions against higher tax rates. For instance, deducting $100 in local tax payments against Iowa’s top state income tax rate can save a taxpayer $8.53, while deducting the same amount against the state’s middle bracket would save just $5.63 in state tax.

Repealing local income tax deductions and using the savings to provide direct state aid to localities most in need would be better targeted. Short of this, Alabama and Iowa could consider subjecting their local income tax deductions to the $10,000 SALT cap, and all four states offering meaningful local income tax deductions could apply broad-based limits on their scope, such as phase-downs or phase-outs.

Finally, the eight states that offer such deductions despite the lack of local income taxes within their borders likely forgo little in tax revenue, but should repeal such deductions nonetheless in order to prevent part-year residents from writing off local income taxes they paid while living in other states. The eight states falling in this category are Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, and Oregon.[31]

FIGURE 14

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap applies to the taxpayer’s combined deduction of both income and property taxes. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, including Louisiana’s allowance only for itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction.

Notes: In the states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap applies to the taxpayer’s combined deduction of both income and property taxes. “State limits” refers to provisions described in Figure 20, including Louisiana’s allowance only for itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

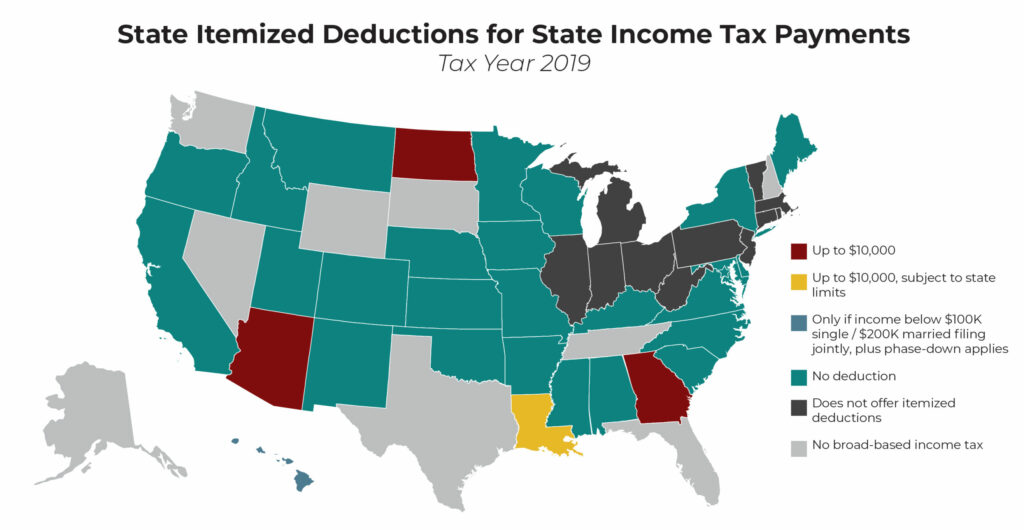

State Income Tax Deductions

The least defensible state itemized deduction is also one of the rarest: state income tax deductions for state income taxes paid. Of the 31 jurisdictions that offer itemized deduction, 25 states and D.C. have chosen to disallow the deduction for state income taxes paid.[32] Only five states allow a partial itemized deduction for state income taxes paid. But there is no policy rationale for allowing taxpayers to deduct a tax from itself.

State income tax deductions have become increasingly rare in recent years. Rhode Island and Vermont each offered such a deduction before repealing them as part of broader reform efforts that eliminated itemization entirely. Oklahoma and New Mexico also offered such deductions in the recent past, though both states have since repealed them.

Even in the states that continue to offer such deductions, their scope has been dramatically reduced relative to just a few years ago. Hawaii, for instance, now denies the deduction entirely for single taxpayers earning over $100,000 and for married couples earning over $200,000 per year. More recently, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, and North Dakota each adopted the federal government’s $10,000 SALT cap, meaning that combined income and property tax amounts above $10,000 are no longer deductible.

FIGURE 15

Notes: In the four states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap applies to the taxpayer’s combined deduction of both income and property taxes. Hawaii’s deduction is uncapped, but is only available to taxpayers below the income levels described and, for married couples earning between $166,800 and $200,000, the deduction is reduced further via a phase-down. Note also that Louisiana only allows itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction.

Notes: In the four states capping this deduction at $10,000, the cap applies to the taxpayer’s combined deduction of both income and property taxes. Hawaii’s deduction is uncapped, but is only available to taxpayers below the income levels described and, for married couples earning between $166,800 and $200,000, the deduction is reduced further via a phase-down. Note also that Louisiana only allows itemized deductions in excess of the federal standard deduction.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

While all these developments are welcome steps forward, the best course of action is to repeal this deduction entirely—ideally in combination with repeal of sales tax deductions in order to prevent taxpayers from claiming sales tax deductions in lieu of income tax deductions (as discussed above). While the federal deduction for state income tax payments exists primarily to aid state governments, such a rationale is inapplicable at the state level as a state cannot provide aid to itself.

As evidence of this, Hawaii tax and budget officials have argued that the deduction amounts to “irrational,” “nonsensical,” and “poor tax policy.”[33] A special tax reform council created by the Georgia legislature informed lawmakers that the state income tax deduction “does not appear to have economic justification.”[34] And prior to repeal of the New Mexico deduction, the state’s legislative finance committee found that while “the federal deduction can be justified as a way of cost-sharing for the cost of state and local government services. The justification for allowing the same deduction for state income tax purposes is less clear.”[35]

Other Itemized Deductions

This report focuses on the most significant itemized deductions—measured by use and revenue impact—offered by the states. It is not a comprehensive account of all deductions that states offer.

Losses associated with theft, natural disasters, or gambling are sometimes deductible, for example, as are investment interest and certain employee businesses’ expenses. Some of these were scaled back or eliminated at the federal level starting in 2018 but not all states conformed to those changes.

Also notable are Alabama and Missouri’s itemized deduction for various types of federal payroll taxes and Montana’s deduction for up to $10,000 of federal income tax payments ($5,000 for single taxpayers). Like itemized deductions in general, the benefits of these deductions tend to skew toward higher-income taxpayers.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

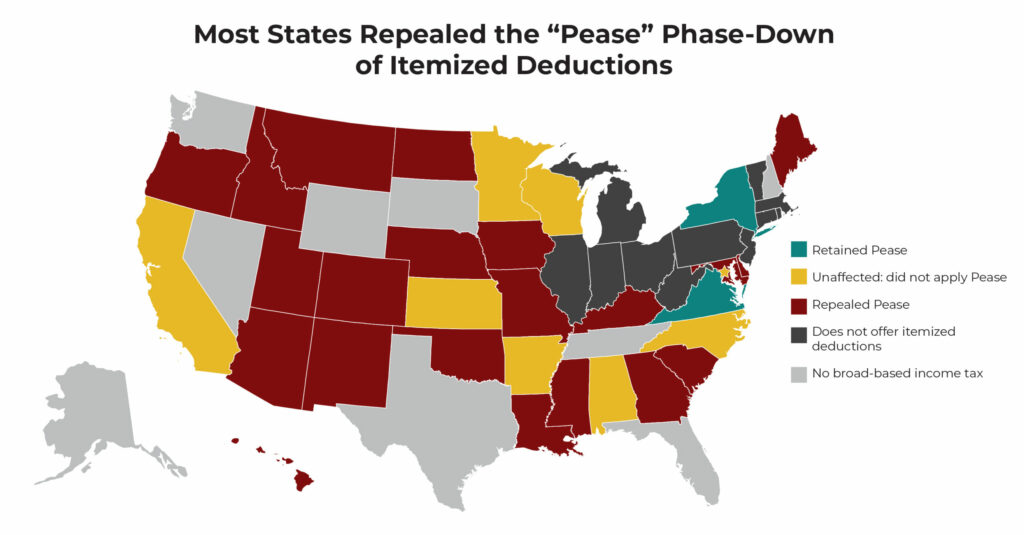

Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions

In addition to paring back specific itemized deductions (e.g., placing a floor under the charitable deduction or eliminating the mortgage interest deduction for second homes), state lawmakers also have options for implementing broader limits on multiple types of deductions.

As recently as 2017 such limitations were the norm in states allowing itemization—only Alabama and Arkansas opted not to apply a high-income phase-down or other limit on deductions in that year.

Fast forward to 2019 and now 18 states—a majority of those that offer itemized deductions—fail to apply broad limits to those deductions when claimed by high-income taxpayers. This rapid change was brought about by the TCJA, which repealed a long-standing limitation on itemized deductions for high-income earners known as the “Pease” phase-down—a provision named after its Congressional sponsor, Rep. Donald Pease.[36] Twenty states lost their own versions of Pease when they coupled their tax codes to that provision of TCJA.

Pease worked by eliminating three cents of most itemized deductions for every dollar of income taxpayers earned above a predetermined level (in 2017, those levels were $261,500 for single filers and $313,800 for married couples). Medical expenses were exempted from the phase-down. A maximum of 80 percent of the affected itemized deductions could be eliminated through Pease (thus making the provision a phase-down, rather than a complete phase-out).

New York and Virginia are the only states that specifically retained Pease in 2019 despite federal repeal, though some other states have their own phase-downs or phase-outs in effect that were not specifically tied to Pease.

FIGURE 16

Note: Reflects policy changes occurring in Tax Years 2018 and 2019. While Maine and Utah both saw Pease disappear, these two states each still apply other types of phase-downs to itemized deductions.

Note: Reflects policy changes occurring in Tax Years 2018 and 2019. While Maine and Utah both saw Pease disappear, these two states each still apply other types of phase-downs to itemized deductions.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

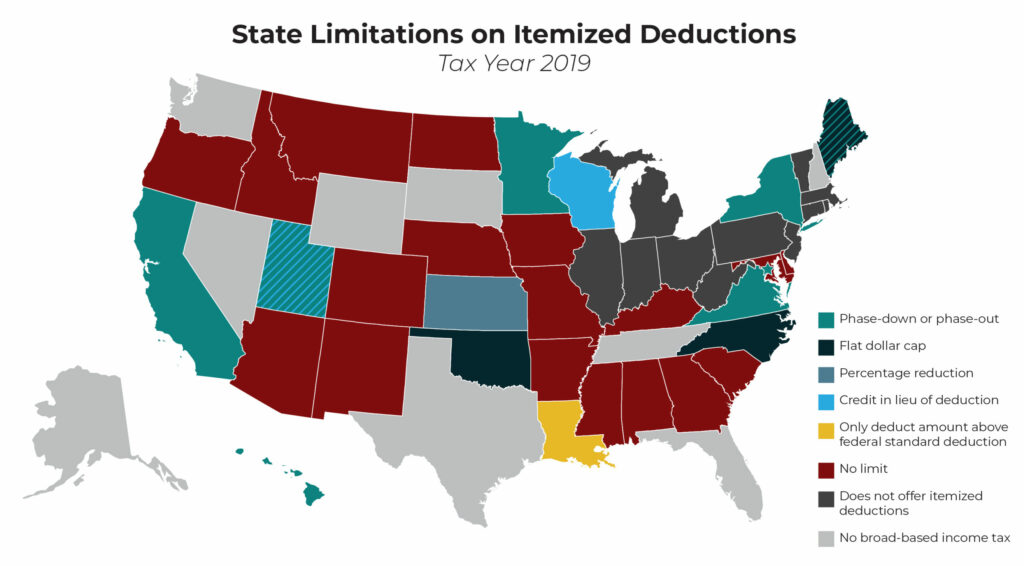

FIGURE 17

Note: Map summarizes itemized deduction limitations that apply to multiple categories of deductions. It, therefore, excludes the $10,000 cap applying only to state and local taxes (SALT) in some states.

Note: Map summarizes itemized deduction limitations that apply to multiple categories of deductions. It, therefore, excludes the $10,000 cap applying only to state and local taxes (SALT) in some states.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) review of state tax forms and recently enacted legislation.

As of Tax Year 2019, 12 states and D.C. still apply a broad limitation to itemized deductions (Kansas’s limitation expired at the end of 2019, however). Itemized deduction limits in place in Tax Year 2019 take six broad forms: phase-downs, phase-outs, flat dollar caps, percentage reductions, credits in lieu of deductions, and only allowing itemized deductions in excess of the standard deduction. Each of these limitations is described below.

- Phase-down: California, Hawaii, Minnesota, New York, and Virginia each apply itemized deduction phase-downs that reduce, by up to 80 percent, certain itemized deductions. All these provisions are applied broadly to the major deductions for charitable giving, home mortgage interest, and state and local taxes, but they exclude medical expense deductions from their scope. New York and Virginia’s phase-downs are based on the Pease provision as it existed prior to the TCJA while the other states’ limitations seem to be based, to varying degrees, on earlier iterations of Pease. Phase-down rates are set at 3 percent in most states, meaning that every dollar of income earned above the specified threshold triggers a 3 percent cut in itemized deductions. California, however, uses a steeper 6 percent phase-down rate. The starting points at which phase-downs begin to take effect vary from a low of $166,800 for married couples in Hawaii to a high of $401,072 for married couples in California, as of 2019.

- Phase-out: Maine, Utah, and the District of Columbia apply itemized deduction phase-outs. These work in much the same way as the phase-downs just described except that they can eliminate the affected deductions entirely for high-income earners, rather than reducing them by up to 80 percent. While D.C. exempts medical deductions from its phase-out, Maine and Utah apply their provisions to all major deductions. Utah phases out itemized deductions (and some other tax reductions) at a very low 1.3 percent phase-out rate, though its phase-out also starts at a much lower income level than in other states ($29,202 for married couples in 2019). Maine, by contrast, applies a more aggressive 20 percent phase-out rate, though it does not begin to take effect until income exceeds $162,950 for married couples.[37] In D.C., a 5 percent phase-out rate takes effect starting at $200,000 of income.

- Flat dollar cap: The most prominent flat dollar cap is the $10,000 SALT deduction cap that exists both at the federal level and in most states allowing SALT deductions. But three states apply other types of flat caps to varying packages of itemized deductions. Maine caps its taxpayers’ maximum itemized deductions at $29,550 in 2019 (this amount rises with inflation each year), though medical expenses are exempt from the cap. North Carolina applies a $20,000 cap to the combined amount of real property tax and mortgage interest deducted by its taxpayers. Oklahoma caps property tax and mortgage interest deductions at a combined $17,000 per year.

- Percentage reduction: In 2019, Kansas allows its residents to deduct just 75 percent of their property taxes, home mortgage interest, and otherwise deductible medical expenses. This limitation has been gradually phasing out and disappears starting in Tax Year 2020.

- Credit in lieu of deduction: Wisconsin and Utah each require taxpayers to convert their itemized deductions into credits before claiming them on their state tax forms. Utah’s credit is worth up to 6 cents per dollar. Because Utah levies a flat income tax rate of just 4.95 percent, this credit makes the subsidies somewhat more valuable than they would be otherwise (a deduction claimed against Utah’s flat tax rate would be worth no more than 4.95 cents per dollar). The choice to offer a credit in lieu of a deduction is more consequential in Wisconsin because that state uses a system of graduated tax brackets with rates ranging from 4 percent to 7.65 percent. If Wisconsin offered a deduction, the tax savings per dollar deducted would be higher for taxpayers in higher tax brackets. By offering a flat 5 percent tax credit, the tax savings per dollar deducted is equalized for itemizing families throughout the income distribution.

- Deduct only amount above standard deduction: Louisiana is unique in limiting itemized deductions by allowing taxpayers only to deduct those itemized deductions that exceed their federal standard deduction.[38] This reduces the cost of itemization but is not well-targeted, as shown in Figure 19. In practice, middle-income taxpayers are unlikely to claim any itemized deductions under this system. Upper-middle-income taxpayers with moderate amounts of itemized deductions will often see their deductions reduced significantly. And very-high-income earners with itemized deductions far in excess of the federal standard deduction will be least affected.

Figure 20 surveys the landscape of state itemized deduction limitations and identifies the deductions to which each limitation applies. While mortgage interest and state and local taxes are always subject to broad-based limits in these states, charitable gifts are occasionally exempt (10 out of 13 jurisdictions apply limits to these deductions) and medical expenses are usually exempt (just 5 out of 13 jurisdictions limit these deductions).

Each of these policy options has different advantages. Phase-downs and phase-outs, for instance, can be calibrated to guarantee that only families with incomes above certain levels will be affected. Percentage reductions, like in Kansas, can preserve some incentive effect for itemizers by reducing deductions rather than eliminating them (though as this article has explained, state itemized deductions offer very little value as incentives anyway). Tax credits can prevent high-income taxpayers in higher tax brackets from reaping a larger tax savings per dollar deducted than middle-income families. And flat dollar caps can narrow the gap between itemizers and standard deduction claimants by ensuring that itemized deductions cannot far exceed the standard deductions claimed by lower- and middle-income families.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

Conclusion

State itemized deductions are regressive tax subsidies that come with a high price tag for state budgets. While many of these deductions are defended as incentivizing desirable behavior (charitable giving, homeownership, school funding, etc.), there is little reason to think that they accomplish these goals in a cost-effective manner.

Recent developments in state itemization have been mixed, with deductions being reduced in some ways and expanded in others. On the one hand, 19 states allowing itemization reined in their property tax deductions by subjecting them to the same $10,000 cap that now applies at the federal level. And 26 states, plus D.C., have pared back the home mortgage interest deduction for recently acquired, highly valued homes. On the other hand, 20 states recently lost the “Pease” phase-down of itemized deductions for high-income earners.

Outright repeal of these regressive, costly, and ineffective policies is an attractive reform. Short of that, states could implement narrow refinements such as putting a floor on the charitable deduction, eliminating the home mortgage interest deduction for second homes, or applying a phase-out or other limitation on itemized deductions broadly. There is no shortage of options for improving on current state itemized deduction policy.

Table of Contents: Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Claims Itemized Deductions? | Revenue and Distributional Effects of State Itemized Deductions | Types of Deductions | Broad Limitations on Itemized Deductions | Conclusion | Appendices

Appendices

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Aidan Davis, Lisa Christensen Gee, and Dylan Grundman for their help in researching this report.

[1] Note that some states require that taxpayers make the same choice on both their state and federal forms even though the package of deductions offered may differ substantially between these two levels of government.

[2] These figures omit households that did not file a return.

[3] Historically, having this choice mattered most for taxpayers who saw the deduction for state income taxes paid tip the scales in favor of itemizing at the federal level. Because state income taxes are usually not deductible at the state level, these taxpayers would sometimes find that the state standard deduction was more beneficial than the package of state itemized deductions available to them. With the capping of the federal SALT deduction at $10,000 starting in Tax Year 2018, however, this situation has become less common.

[4] Taxpayers in this situation can itemize on their federal tax forms in order to make itemization possible at the state level as well, but this is relatively rare in practice. It is unusual that accepting fewer federal deductions in return for more state deductions would result in a net tax cut because federal income tax rates are significantly higher than state tax rates.

[5] Taxpayers for whom the state and local income tax deduction tipped the scales in favor of itemizing at the federal level are the exception, as this deduction is not available in New Mexico or D.C.

[6] The ITEP Model actually groups people into tax units (meaning, in most cases, groups of people that file one tax return), but this report uses the word “households” to describe these groups as it is more familiar to most readers.

[7] A discussion of the ITEP Model methodology is available online at https://itep.org/itep-tax-model. This calculation was performed by estimating the impact of repealing Maryland itemized deductions while leaving the standard deduction in place. It therefore reflects the fact that current itemizers would switch to claiming the standard deduction instead. These figures omit the impact of itemized deductions on local income tax revenues as well as the revenue loss associated with itemized deductions flowing to nonresidents.

[8] This is the potential benefit of claiming a $4,500 standard deduction (the maximum for married couples) against the state’s top income tax rate of 5.75 percent.

[9] Meg Wiehe et al., “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, 6th Edition,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Oct. 2018.

[10] While differences between these racial and ethnic groups are the focus here, it is important to acknowledge that each group itself includes people of diverse backgrounds and economic conditions, and intersects with other dimensions of inequality such as gender and sexuality.

[11] Joseph Bankman et al., “State Response to Federal Tax Reform,” State Tax Notes, May 7, 2018, p. 557-589.

[12] Arizona is a rare exception, though even there non-itemizers can only deduct one-fourth of their charitable contributions (see Arizona Revised Statutes, Section 43-1041(I)).

[13] In this example, neither taxpayer would access the deduction. Taxpayer 1 would receive no charitable deduction because their giving amounted to less than 5 percent of their income. Taxpayer 2 would continue to find that claiming the standard deduction would result in a lower tax bill than claiming the charitable deduction and other itemized deductions.

[14] Kamila Sommer and Paul Sullivan, “Implications of US Tax Policy for House Prices, Rents, and Homeownership,” 2018, American Economic Review, 108 (2): 241-74.

[15] The TCJA also led to state mortgage interest deductions being put out of reach for many families in states that require federal standard deduction claimants to claim the state standard deduction, and in states that opted to increase their own standard deductions because of the new federal law.

[16] A more thorough compilation of IRS data pertaining to the mortgage interest deduction is available in Appendices C through E.

[17] Jim Tankersley and Ben Casselman, “As Mortgage-Interest Deduction Vanishes, Housing Market Offers a Shrug,” The New York Times, Aug. 4, 2019.

[18] This assumes that the buyer made a 10 percent down payment on a $300,000 home and has a 30-year mortgage of $270,000 at an interest rate of 4 percent. In this case, interest payments in the first year should be $10,713. Deducting this amount against a 7 percent tax rate would yield $749.91 in annual tax cuts or $62.49 per month. The actual tax cut would be lower if the buyer’s itemized deductions exceed their potential standard deduction by less than $10,713.

[19] Kerwin Kofi Charles and Erik Hurst, “The Transition to Home Ownership and the Black-White Wealth Gap,” Feb. 2002, Review of Economics and Statistics 84(2): 281-297.

[20] Misha Hill et al., “The Illusion of Race-Neutral Tax Policy,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Feb. 2019.

[21] Wisconsin Statutes Section 71.07(5)(a)(5).

[22] Estimate prepared by Kyle Easton, Oregon Legislative Revenue Estimate, on Feb. 21, 2019.

[23] This is also true of the casualty and theft deduction at some points in the income distribution, but we do not consider it to be a major deduction since preliminary IRS data suggest that less than 16,000 returns claimed that deduction in Tax Year 2018.

[24] Property taxes on business property are typically deductible as business expenses under separate provisions in state law.

[25] Aidan Davis, “Property Tax Circuit Breakers in 2019,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Sep. 26, 2019.

[26] Author’s analysis of IRS data for Tax Year 2017 contained in Historic Table 2 (SOI Bulletin).

[27] Ibid. The average itemizer in Wisconsin claimed $50 in personal property tax deductions on their federal tax forms in 2017, while in D.C. the comparable figure was $59.

[28] Ibid.

[29] A family of four earning over $300,000 and living in the 20879 zip code would be allowed a general sales tax deduction of $1,965 in 2019 if they used the IRS’s sales tax deduction calculator.

[30] See supra note 26. It is also possible that some of these taxpayers were not residents of Delaware or Montana in 2017, as a footnote accompanying the IRS’s Historic Table 2 indicates that some taxpayers may be classified based on “the address of a tax lawyer, or accountant, or the address of a place of business.”

[31] Note that some Oregon localities levy income taxes that are paid by employers rather than employees. These taxes cannot be claimed as itemized deductions by Oregon individuals.

[32] To be clear, the District of Columbia does not allow a D.C. tax deduction on income taxes paid to D.C. or to any state.

[33] Frederick D. Pablo, “Testimony of the Department of Taxation Regarding SB 570 SD1,” delivered before the Senate Committee on Ways & Means, March 3, 2011. See also Dean Hirata, deputy director of the Department of Budget and Finance, as quoted in: Derrick DePledge, “Tax deduction repeal would pinch majority,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Feb. 17, 2011.

[34] Recommendations of the Special Council on Tax Reform and Fairness for Georgians (2011).

[35] Legislative Finance Committee, “Fiscal Impact Report for HB 270/aHTRC,” Feb. 7, 2010.