Even as the nation recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, we cannot turn away from the inequities on which it shone a bright light. The richest among us grow richer by the day, but far too many families cannot make ends meet.

Fortunately, a growing group of state lawmakers are recognizing the extent to which low- and middle-income Americans are struggling and the ways in which their state and local tax systems can do more to ensure the economic security of their residents over the long run.

To that end, lawmakers across the country have made strides in enacting, increasing, or expanding tax credits that benefit low- and middle-income families. Here is a summary of those changes and a celebration of those successes.

New or Newly Funded Credits

Washington state has had an Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) on the books since 2008. But it wasn’t until this year that lawmakers took steps to improve its structure and fully fund its implementation. The state’s Working Families Tax Credit is modeled after the federal EITC and enhanced through added improvements: the inclusion of immigrant families and effectively eliminating the phase-in so that all families with any amount of earned income can qualify for the full value of the credit.

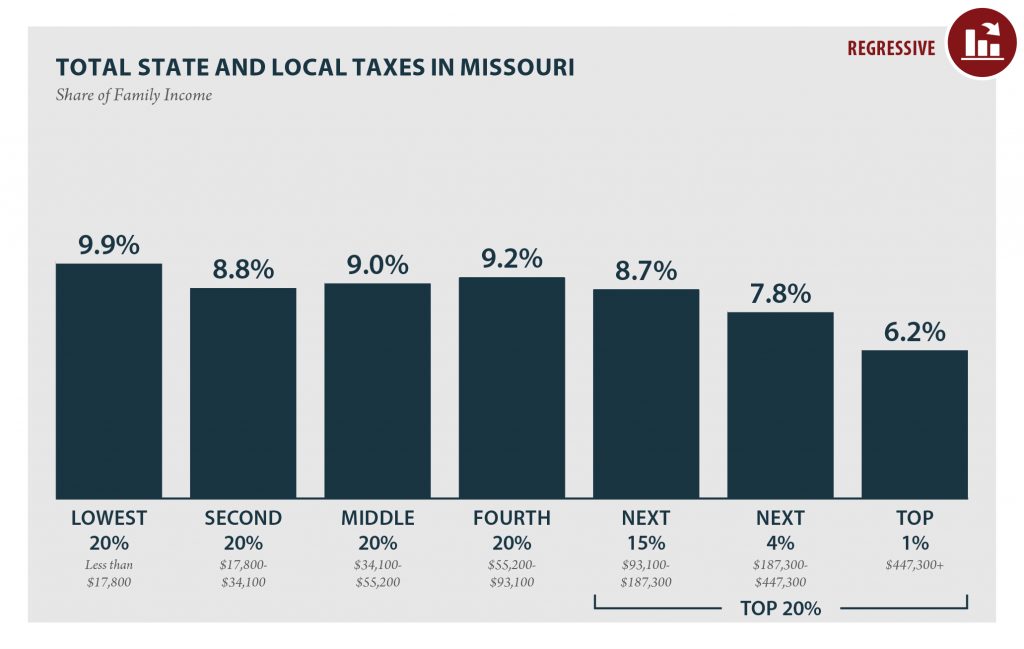

In Missouri—following 25 years of sustained advocacy—organizers and beneficiaries celebrated the legislature’s passage of a state-level EITC, set to go into effect in 2023. Missouri will join 29 other states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico in offering such a credit. While this is a major policy success, the state credit is non-refundable and lower-income taxpayers will not receive a refund for the portion of the credit that exceeds their income tax bills. This limits the ability of the credit to offset the Show-Me State’s regressive state and local taxes and should be reformed in the years ahead.

Increased Credits: More of a Good Thing

Colorado increased its state-level EITC to 20 percent (up from 15 percent) starting in 2022. The credit will temporarily increase even further (to 25 percent) between 2023 and 2025, before reverting to a 20 percent credit in 2026. The higher credit amount is coupled with an age expansion, lowering eligibility to permanently include adults without children in the home who are between the ages of 19 and 24.

Colorado also funded a targeted state-level child tax credit (CTC) for single filers making less than $75,000 and joint filers making less than $85,000. The credit will be available to children who do not have Social Security numbers (a requirement that limited the CTC’s reach under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act). Even in its enhanced form, the federal CTC continues to leave behind non-citizen children.

Maryland lawmakers enacted possibly the most robust, albeit temporary, enhancements to their state-level EITC. They increased the credit to 50 percent of the federal credit, with full refundability. The state also extended its EITC to immigrant workers who file taxes using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) and previously expanded it to workers without children in the home aged 18 through 24.

Lawmakers in New Mexico increased their state credit, known as the Working Families Tax Credit, from its current 17 percent to 25 percent by 2023. They also extended eligibility to ITIN filers and younger workers, 18 through 24, without children in the home.

Connecticut lawmakers took steps this session to restore their state-level EITC to 30 percent (up from 23 percent). And Indiana increased its credit from 9 to 10 percent.

In Oklahoma, lawmakers restored refundability to their state-level EITC. The credit, set at 5 percent of the federal, was made non-refundable in 2016 in response to a budget shortfall. Restoring refundability goes a long way in ensuring that recipients can receive their full credit, regardless of whether it exceeds the personal income taxes they owe.

Enhanced Eligibility

States have also made headway in expanding their EITC credit eligibility to include families left out of the federal credit. This includes younger and older workers without children in the home who receive no benefit from the permanent federal EITC. It also includes immigrants who file their taxes usingITINs, who were largely left out of the federal stimulus relief, and who are too often left behind when it comes to key policies that aim to mitigate poverty.

Age Expansion

Seven states have now recognized the need to allow young workers to enjoy the benefits of the EITC.

Maryland and New Mexico took steps this year to lower the age of their existing credits to include 18 through 24-year-old workers without children in the home. These states join California, Colorado, Maine, Minnesota, and New Jersey, all of which have made permanent enhancements—with eligibility beginning between ages 18 to 21—to lower age eligibility for workers without children in the home. New Jersey, in its recent budget agreement, lowered the age eligibility from 19 to 18 and expanded the credit to those 65 and older. California led the way on removing the age cap for older workers, making the state-level credit available to older workers who remain in the workforce past age 64.

ITIN Inclusion

Last year, California and Colorado became the first states to expand their state-level EITCs to include immigrant families who work and pay taxes but are excluded from the federal credit (PDF). These families file taxes using Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITIN). Four additional states have since followed their lead. Just this year, Maryland, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington state expanded their EITC payments to include ITIN filers.

While there is always more work to be done, there is plenty to celebrate this year in terms of permanent enhancements to state-level EITCs that will have long-term impacts on improving the economic security of families across the country. A far more worthy goal than the ill-targeted tax cuts under consideration across the country.