Note: Estimates for the Working Families Tax Relief Act were revised on September 10, 2019.†

Read as PDF

Data available for download

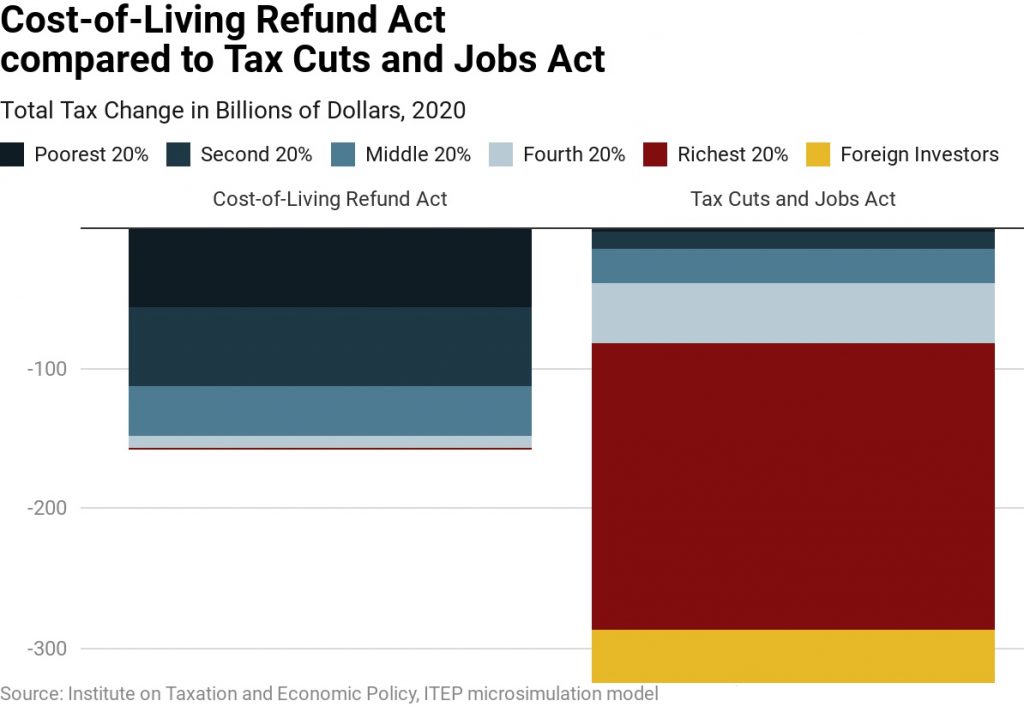

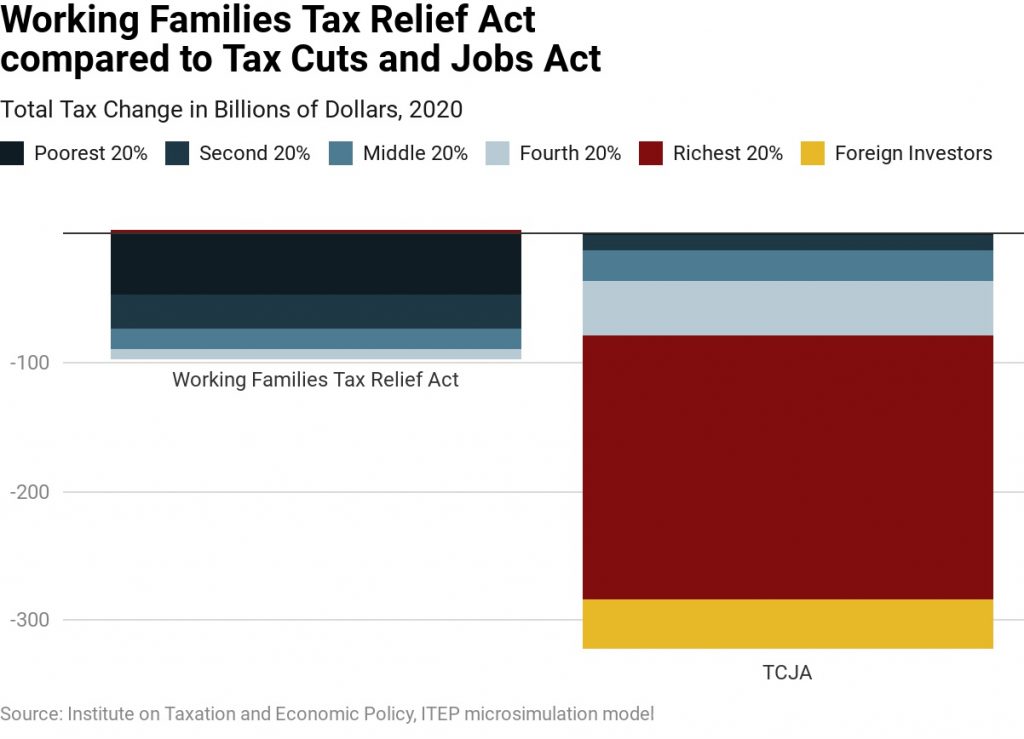

Federal lawmakers have recently announced at least five proposals to significantly expand existing tax credits or create new ones to benefit low- and moderate-income people. While these proposals vary a great deal and take different approaches, all would primarily benefit taxpayers who received only a small share of benefits from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

The Five Tax Credit Proposals

Economic inequality, stagnating wages for working people and child poverty are recognized as some of the defining challenges for America today.[1] One possible response to these challenges is to use the tax code to supplement incomes of low- and moderate-income people. This report examines five proposals to create or expand tax credits to accomplish this goal, explains how they differ from each other and provides estimates of their impacts using the ITEP microsimulation model.[2]

This report focuses on the big picture to help policymakers and the public understand and distinguish between the five proposals. ITEP has generated supplemental data providing more detail for each proposal, which you can find at the following links:

Cost-of-Living Refund Act American Family Act

Working Families Tax Relief Act

LIFT the Middle Class Act Rise Credit

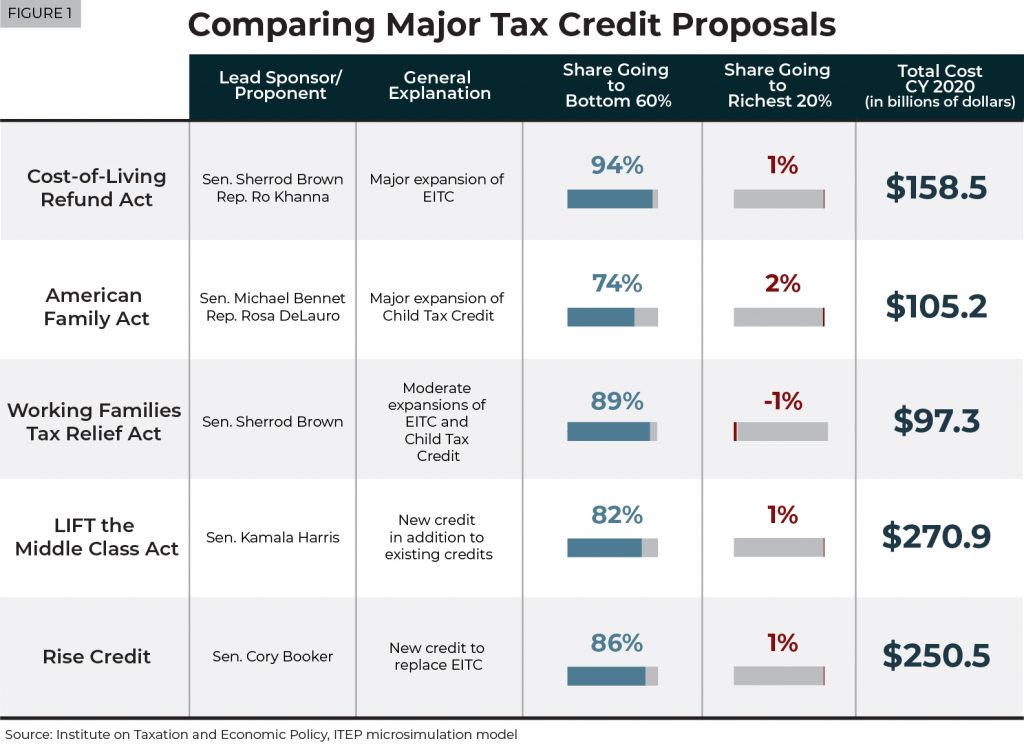

As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposals vary a great deal in their approach. The Cost-of-Living Refund Act would expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) while the American Family Act would expand the Child Tax Credit. The Working Families Tax Relief Act makes less dramatic changes to both credits and combines them in one bill.

The LIFT the Middle Class Act and the Rise Credit would create new tax credits. The Rise Credit initially seems more generous because it is larger than the credit provided by the LIFT Act; however, the Rise Credit would replace the current EITC while the LIFT Act would coexist alongside the EITC.

Each proposal takes a different approach to using tax credits to boost incomes of low- and moderate-income families, makes distinct choices about where to target the benefits, and varies in the size of the investment. For example, the Working Families Tax Relief Act is most targeted to low-income taxpayers and has the lowest cost ($97.3 billion in 2020, as shown on Figure 1). The American Family Act has a similar cost but targets resources toward children, which is motivated by research showing that expanded child tax benefits would have a significant impact on reducing child poverty.[3] The Cost-of-Living Refund Act provides the largest expansion to the EITC and, therefore, arguably provides the greatest increase in work incentives for its cost.

The costliest of the proposals are the LIFT the Middle Class Act (estimated to cost $270.9 billion in 2020) and the Rise Credit (estimated to cost $250.5 billion in 2020). As a result, these two proposals provide the most generous benefits to most households, but this is not true across the board, as this report will explain.

This analysis is inevitably incomplete because these tax credit proposals would certainly, if enacted, be paired with other tax provisions that raise revenue to offset the costs and possibly other provisions that benefit households in certain situations. The goal of this report is not to evaluate one proposal as being more favorable than others but to understand how they differ from each other and from current law based on what we know about them so far.[4]

All Five Proposals Target Groups that Benefited Little from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

One thing is true about all these proposals—they are far more targeted toward low- and middle-income people than the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).[5]

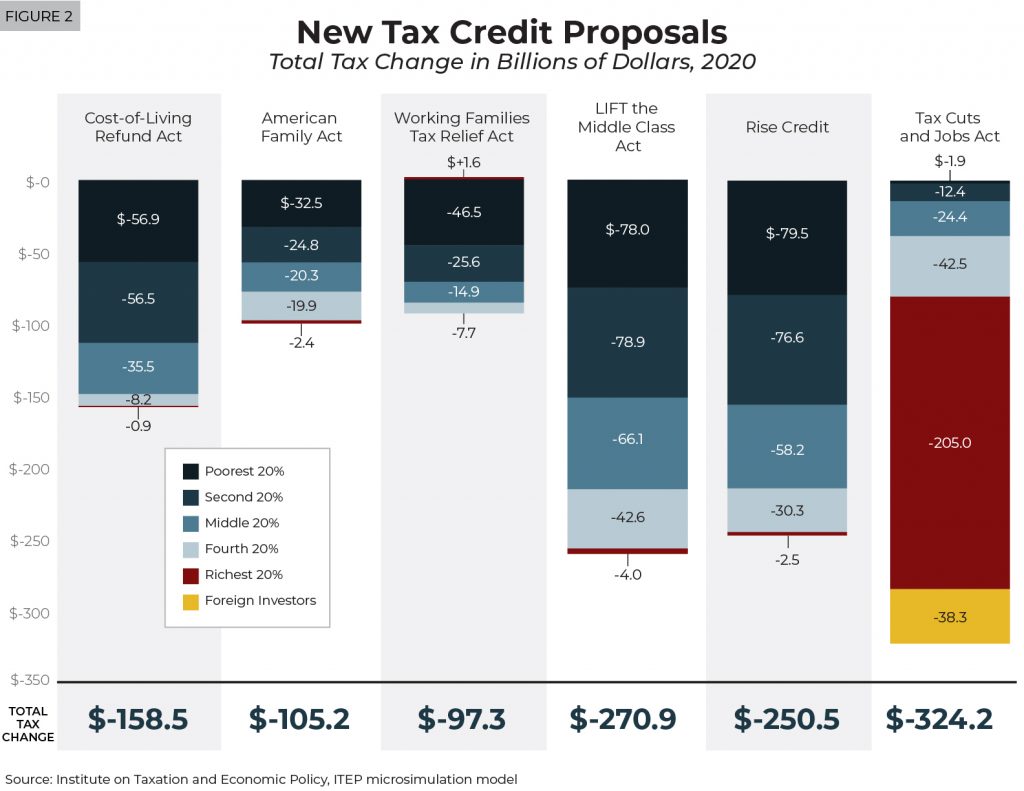

Figure 2 compares the cost and distribution of benefits of each of the five proposals in 2020 to the cost and distribution of benefits from TCJA.

ITEP uses its microsimulation model to estimate the benefits for tax units in each income group. A tax unit includes all the people who are listed on a personal income tax return, not counting returns filed by dependents. A tax unit includes an adult or two married adults and also includes the adults’ dependents (usually children).[6]

As illustrated in Figure 2, TCJA provided the vast majority of its benefits to the richest fifth of tax units, which will have incomes greater than $119,000 in 2020. It also provided significant benefits to foreign investors, who gain from TCJA’s cuts in the corporate income tax. By contrast, all five tax credit proposals examined in this report focus the vast majority of their benefits on the bottom three-fifths of tax units, which will have incomes of less than $69,800 in 2020.

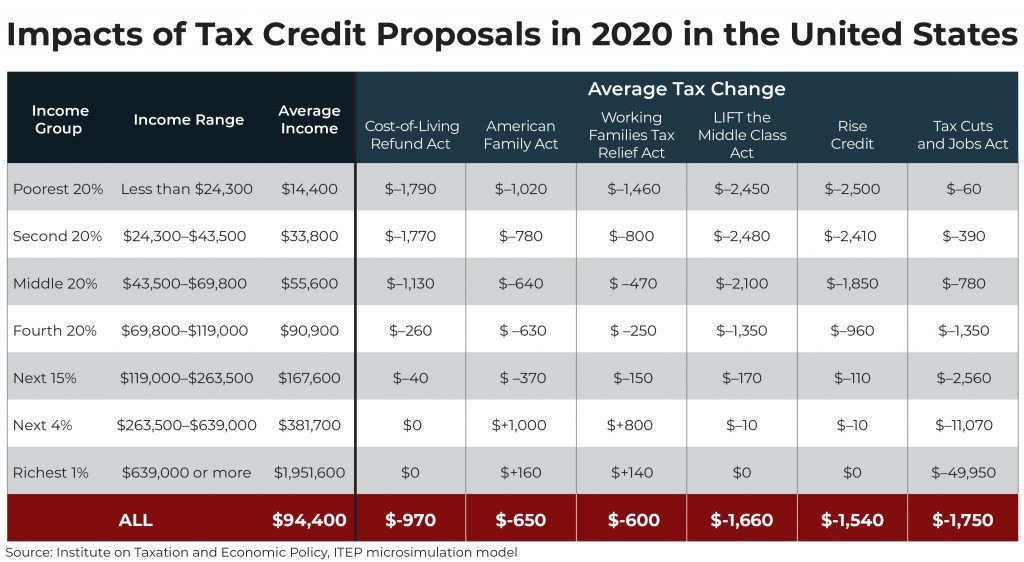

Figure 3 provides the estimated average tax cut for each income group under each proposal and under TCJA. As already mentioned, these estimates are incomplete. If lawmakers enacted one of the tax credit proposals, it would likely be paired with other tax provisions to raise or cut taxes, so the total effect of such a package of tax changes is impossible to know right now. For example, one of the tax credit proposals could be enacted along with repeal of part or all the TCJA, as well as other provisions, to raise revenue.[7]

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of each tax credit proposal on its own and compares that to TCJA. For example, it demonstrates that the tax break received by the typical family in the bottom two-fifths of tax units under any of the tax credit proposals would be larger than the tax breaks they received under TCJA.

On the other hand, the tax credit proposals would provide almost nothing to well-off families and in some cases would raise their taxes.

The details of the five tax credit proposals make clear how they benefit low- and moderate-income Americans rather than the well-off.

Proposals to Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit

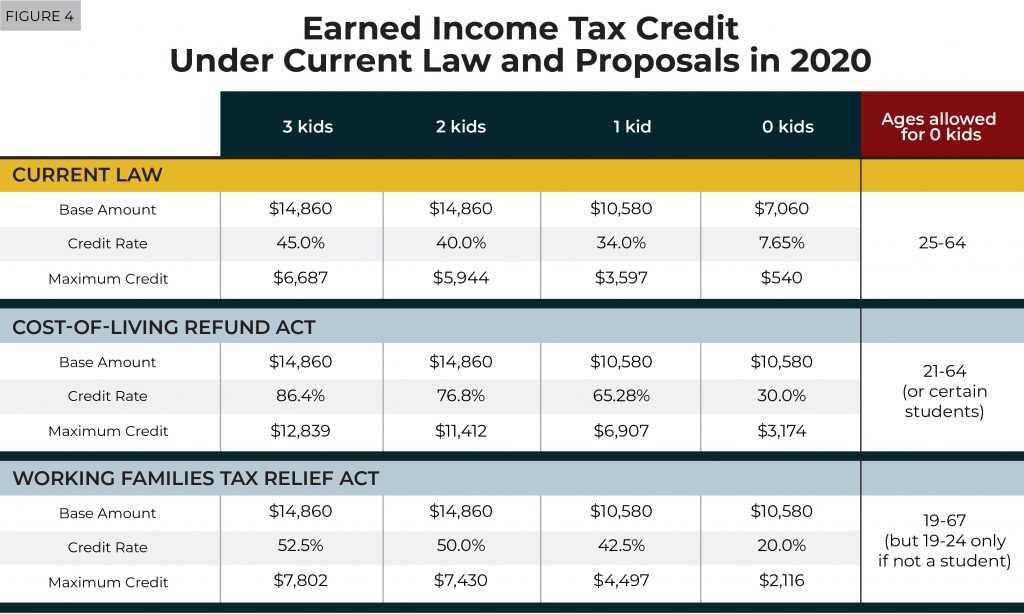

The EITC is a tax credit equal to a certain percentage of earnings up to a maximum amount. The EITC in its current form is most helpful to working people with children. For example, those with one child in 2020 will be allowed an EITC equal to 34 percent of their earnings, up to a likely maximum of $10,580 in earnings, resulting in a maximum credit of $3,597.[8] The credit will begin to phase out if the family’s income exceeds $19,410 (or $25,310 in the case of a married couple). The credit rate and the earnings amount to which it applies is higher for families with two children and still higher for families with three or more children.

As Figure 4 illustrates, families with children would see their maximum EITC nearly doubled under the Cost-of-Living Refund Act and increased by smaller amounts under the Working Families Tax Relief Act.

For families with children, neither proposal would directly change the phaseout rules, but because the maximum credit would be larger, it would phase out at higher income levels, meaning more people would benefit from the EITC.

The most significant changes under both proposals would be for individuals or married couples with no children living with them. Under current law, the maximum EITC for this group will be roughly just $540 in 2020. Under the Cost-of-Living Refund Act, the maximum EITC for this group would be nearly six times that amount; and under the Working Families Tax Relief Act it would be nearly four times that amount, as illustrated in Figure 4. Both proposals would allow more people without children to benefit from the EITC by phasing it out at higher income levels compared to current law and by loosening age restrictions, as illustrated in Figure 4.

The Cost-of-Living Refund Act also provides an EITC of $1,200 to certain students and those with children under age seven even if their earnings fall below what would otherwise qualify them for that amount.

More details on the proposed changes to the EITC are provided in the appendix.

Proposals to Expand the Child Tax Credit

Under current law, taxpayers are allowed a Child Tax Credit (CTC) of up to $2,000 per child.[9] Limits on the refundable portion of the CTC prevent about a third of low- and moderate- income children and families from receiving the full credit.[10] A smaller number of children and families do not receive the full credit because their incomes are too high. The CTC starts to phase out for married couples with incomes over $400,000 and other families with incomes over $200,000.

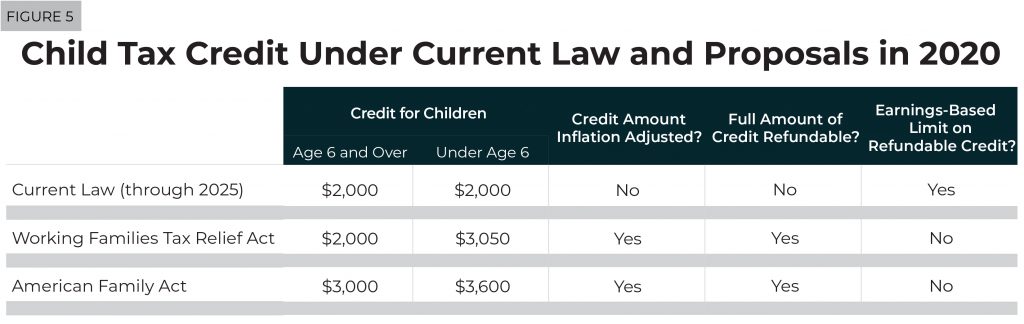

Both the American Family Act and the Working Families Tax Relief Act would increase the credit, remove the limits on refundability that prevent low- and moderate-income families from benefiting and lower the income limits that prevent well-off people from receiving the full credit.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the American Family Act would increase the CTC to $3,000 in 2020 and provide an additional $600 for each child under 6 years old. The Working Families Tax Relief Act would maintain the $2,000 credit and provide an additional $1,000 for children under 6. (The figures shown in Figure 5 include inflation adjustments for 2020 where they apply.)

In many cases, tax credits benefit low-income people only to the extent that they are refundable. Both of these proposals would remove the two limits on the refundable part of the CTC that prevent low-income families from accessing the full credit under current law.

First, under current law the credit is limited to a percentage of earnings, not counting the first $2,500.[11] This means that families with very low earnings will not receive the credit or receive only a partial credit. Superficially this resembles the way the EITC is calculated as a percentage of earnings, but the CTC’s earnings-based limit is more difficult to justify. While the EITC is thought of as tax break designed to encourage work, the CTC is a per-child credit, designed mainly to help families with the costs of raising children. The earnings-based limit is inconsistent with this overall design because it restricts the value of the credit for each child in a low-income household. Also, the CTC is allowed for families at very high income levels compared to the EITC, meaning it is not designed to be a work incentive for the vast majority of households who benefit from it.

Second, under current law, the refundable part of the CTC is also subject to a dollar cap that will likely be $1,400 in 2020.[12] This provision has no apparent rationale other than to restrain the overall cost of TCJA, which provided the vast majority of its benefits to the well-off, as already explained.

Both the American Family Act and the Working Families Tax Relief Act would eliminate these limits on the refundable part of the CTC.

In addition, both proposals would lower income levels at which the CTC begins to phase out. The American Family Act would reduce those thresholds from $400,000 to $180,000 for married couples and from $200,000 to $130,000 for other families. The Working Families Tax Relief Act would lower those thresholds from $400,000 to $200,000 for married couples and from $200,000 to $150,000 for other families.

The changes to income limits in the CTC are the reason Figure 3 shows that these two proposals would increase taxes on some high-income Americans (but not among the richest 1 percent, who are already generally ineligible for the CTC under current law).

More details on the proposed changes to the CTC are explained in the appendix.

Proposals to Enact New Tax Credits

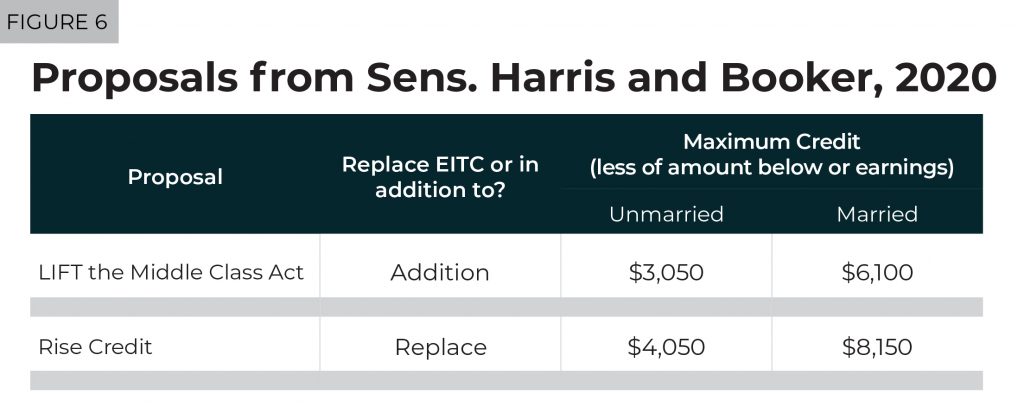

The LIFT the Middle Class Act and the Rise Credit both create new refundable credits. The LIFT Act would provide a maximum credit of $3,000 for unmarried people and $6,000 for married couples. The Rise Credit would be a maximum of $4,000 for unmarried people and $8,000 for married couples. (The amounts shown in Figure 6 include inflation adjustments for 2020.)

The Rise Credit is larger and therefore seems like the more generous of the two, but this is not always true because the Rise Credit is designed as a replacement for the EITC, whereas the credit provided by the LIFT Act would supplement the EITC.

Similar to existing tax credits, both proposals can be thought of as having two types of limits: a low earnings-based limit and a high-income limit.

Under the LIFT Act and the Rise Credit, the low earnings-based limit bars most people from receiving a credit exceeding their earnings. For example, the maximum credit allowed under the LIFT Act in 2020 is likely to be $3,050 for unmarried people. The maximum credit would effectively be $3,050 or the unmarried person’s earnings, whichever is less. The same type of rule applies under the Rise Credit. This is similar to how the EITC is phased in based on earnings, except that the credit rate in the case of the LIFT Act and Rise Credit is 100 percent.

The LIFT Act provides an exception to the earnings-based limit by allowing students to count their Pell Grants as earnings for the purposes of calculating their credit. (Figures in this report do not include the impact on such students.)

The Rise Credit provides two exceptions to the earnings-based limit. It allows caregivers of certain dependents (elderly or disabled dependents and children under 6 years old) and certain students to receive the full credit regardless of their earnings. (Figures in this report do not include the impact on such students.)

The other limit on both credits is the high-income limit. In 2020, the LIFT Act’s credit would start to phase out, generally, for single, childless people as their income exceeds $30,550 and for other families as their income exceeds $61,150. The Rise Credit would begin to phase out for married couples as their income exceeds $50,950 and for other families as their income exceeds $30,550 in 2020.

The Rise Credit has an additional feature. Its basic credit ($4,000/$8,000, adjusted for inflation) does not take children into account. Because it would replace the EITC (which does take the number of children a family has into account) the basic credit would provide little or no benefit to single parents with two or more children. For this reason, the Rise Credit includes an additional component that effectively is like a small EITC for these families.[13]

More details about these proposed credits are provided in the appendix.

All Five Tax Credit Proposals Target the Bottom 60 Percent, But Impacts Depend on Family Structure

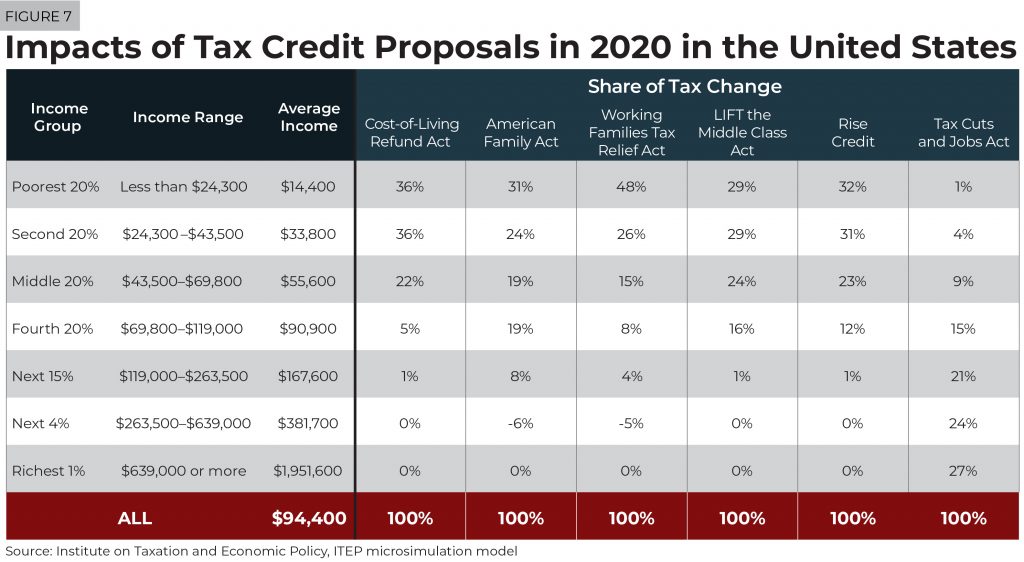

Given the details of the tax credit proposals, it is clear that they are intentionally designed to target benefits to low- and moderate-income people rather than the well-off. Figure 7 provides the share of benefits going to each income group under each proposal and TCJA.

These estimates demonstrate that the proposals are intended to benefit those in the bottom three-fifths of tax units.

These proposals are also designed to help families with working age adults. To be eligible for tax credits under any of these proposals, one must either have earnings or have dependents. While many seniors have earnings and some seniors have dependents (for example, those with custody of grandchildren), most retirees do not benefit from these tax credit proposals.[14]

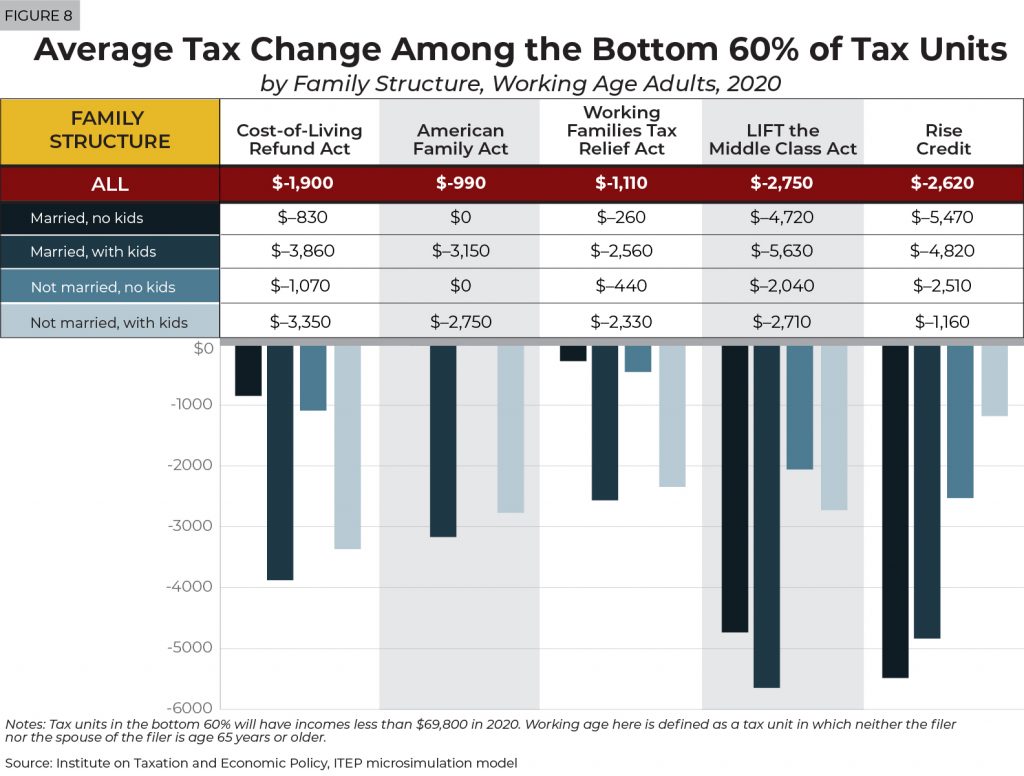

To get a better sense of how the intended beneficiaries of these proposals are affected, Figure 8 focuses on tax units that meet two conditions. One, they are among the bottom three-fifths of tax units overall. Two, they are tax units with working age adults.

Figure 8 shows the average tax change under each proposal in 2020 for those tax units among the bottom three-fifths with working age adults.[15] In other words, this graph shows the average tax change among those whom the proposals are designed to help.

The largest average tax breaks are provided by the LIFT Act and Rise Credit, which is not surprising because these two proposals are, by far, the most expensive, as illustrated in Figure 1 in the beginning of this report.

Figure 8 also illustrates the average tax change for the same group—those among the bottom three-fifths and including working age adults—but separated into different family structures.

Again, this analysis is incomplete because we do not know what other tax provisions would be enacted along with these proposals. Nonetheless, this analysis demonstrates that the impacts of the tax credit proposals alone would vary greatly by family structure.

For example, it shows that those without children (married couples with no children and unmarried people with no children) would receive the largest average tax break from the Rise Credit. This is not surprising given that the basic Rise Credit is $4,000 for unmarried people and $8,000 for married couples, with only a small adjustment based on the number of children in the family.

The situation is different for people with children. Married couples with children would receive the largest average tax break under the LIFT Act, partly because the LIFT Act is one of the most generous proposals across the board. Single parents with children would receive the largest average tax break under the Cost-of-Living Refund Act, which expands the EITC and continues the policy of providing a larger EITC to larger families.

As explained earlier, the proposals vary in how they reach a similar goal of targeting tax cuts to low- and middle-income taxpayers. For example, some proposals are more generous than others, but come with higher costs. While the American Family Act does not provide the largest benefits across taxpayers, it is less costly than most of the other proposals, and it directs resources entirely to families with children especially very low-income families.

Tax Credit Proposals Would More Equitably Target Their Benefits By Race and Ethnicity

Research shows that tax policy can exacerbate racial and ethnic gaps in income, wealth, and opportunity, which reflect the legacy of a variety of injustices and continued discrimination.[16]

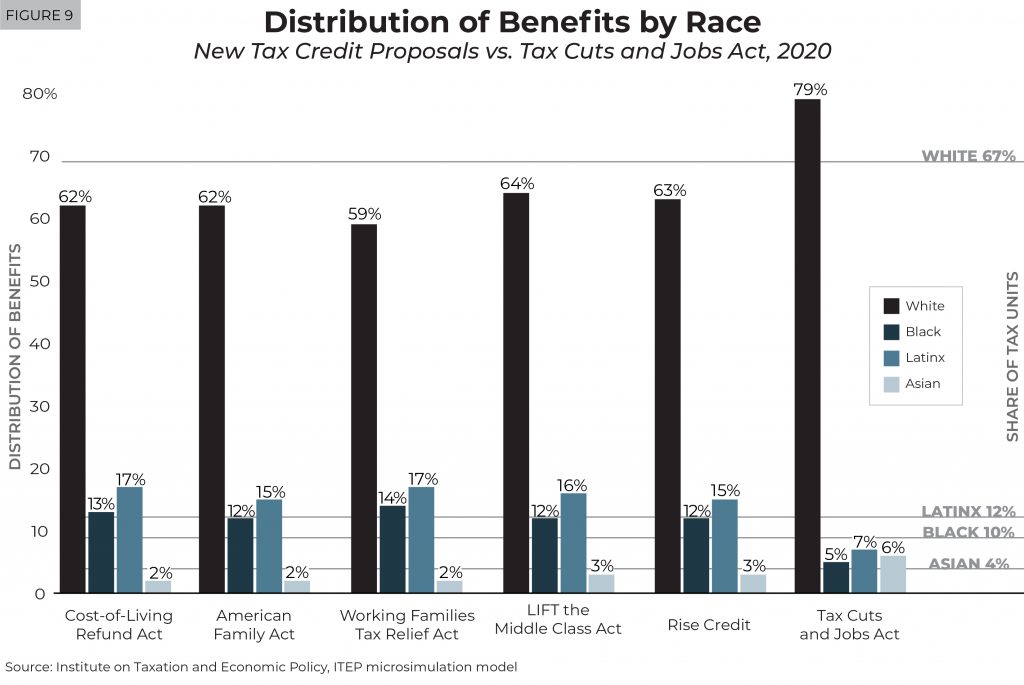

The TCJA, for example, showered 79 percent of its benefit on white taxpayers (see Figure 9) and rewarded their existing wealth by concentrating the greatest share of its cuts on corporations and the highest-income households, exempting even more of the nation’s richest families from the estate tax, and leaving in place provisions that tax investment income at lower rates.[17]

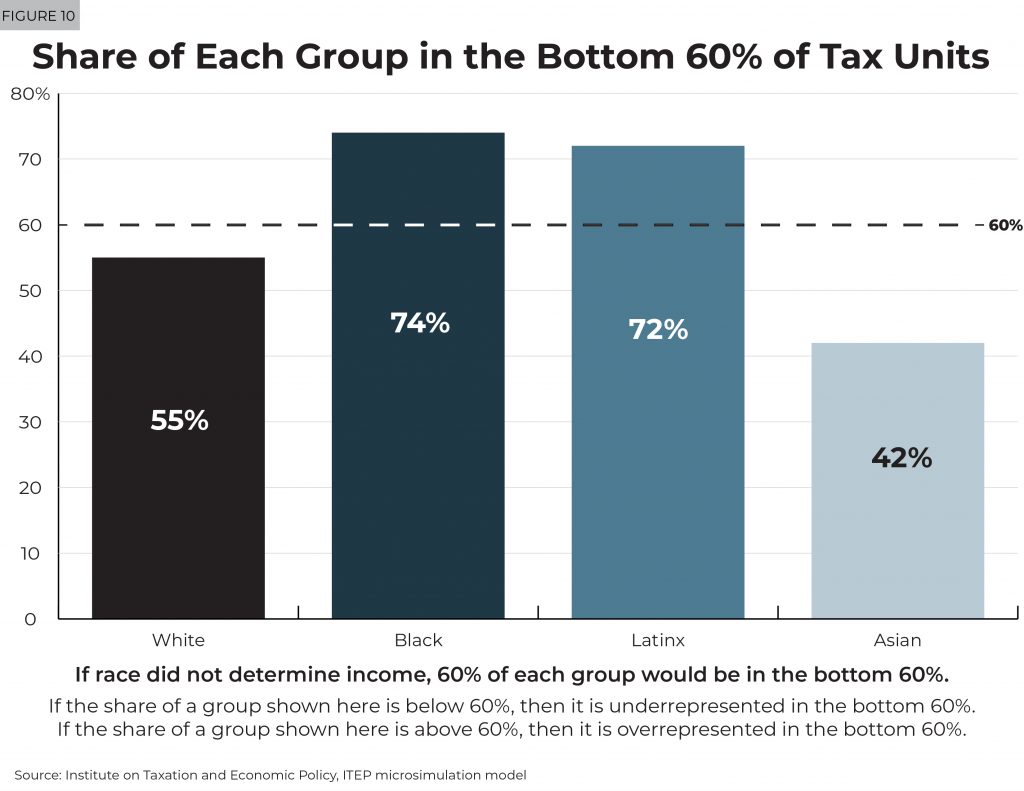

The five tax credit proposals examined in this report would, to some degree, help to mitigate existing racial disparities in income and the tax code. All five of the tax credit proposals are designed to target benefits to and boost the incomes of the bottom 60 percent of taxpayers, and Black and Latinx make up a disproportionate share of these income groups due to historic and continuing systemic injustices.

Figure 10 illustrates the share of each racial and ethnic group that is among the bottom 60 percent of tax units. For example, 74 percent of Black tax units and 72 percent of Latinx tax units have incomes that place them in the bottom 60 percent of tax units, meaning both groups include a greater share of taxpayers that the tax credit proposals are designed to help. However, only 55 percent of all white non-Hispanic taxpayers have incomes that place them in this group.

Conclusion

Policymakers have several tools to address economic inequality, stagnating wages and child poverty. One of those tools is the tax code. As this report makes clear, the five major tax credit proposals that have been offered so far would all do this to different degrees and in different ways. The proposals meet different goals and have different costs, but all of them target the vast majority of their benefits to the bottom 60 percent of Americans, who only receive a small share of the benefits from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Whereas TCJA disproportionately benefited the richest fifth of Americans, the benefits of these proposals would be distributed more equitably.

Appendices

† The revisions made on September 10 for the Working Families Tax Relief Act were relatively small. For example, our estimate of the bill’s cost in 2020 changed from $99.2 billion to $97.3 billion.

[1] For information on rising wage inequality and wage trends, see Elise Gould, “State of Working America Wages 2018: Wage inequality marches on— and is even threatening data reliability,” Economic Policy Institute, February 20, 2019. For an overview of the disparate frequencies of child poverty by race and ethnicity, see Valerie Wilson and Jessica Schieder, “The rise in child poverty reveals racial inequality, more than a failed War on poverty,” Economic Policy Institute, June 8, 2018.

[2] The ITEP microsimulation model estimates the impacts of tax policies on a representative sample of taxpayer records. For more information, see the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model Overview, https://itep.org/itep-tax-model.

[3] See National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. 2019. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC

[4] When possible, this analysis is based on the legislative text for each proposal. One of the proposals, the Rise Credit, is not fleshed out in legislative text but was announced by Sen. Cory Booker’s presidential campaign. However, it is based on a proposal from the Economic Security Project, which has provided sufficient detail for this analysis.

[5] It is worth keeping in mind that the TCJA follows a longer trend whereby recent tax cuts have disproportionately benefited the highest-income Americans. Since 2000, tax cuts have reduced federal revenue by $5.1 trillion, and 65 percent of the value of those breaks has gone to the top 20 percent of tax payers. See Steve Wamhoff and Matthew Gardner, “Federal Tax Cuts in the Bush, Obama, and Trump Years,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 11, 2018.

[6] A tax unit is often the same thing as a household, but not always. For example, three unmarried, unrelated adults might live in a house together and be considered a household, but they would likely each file separate tax returns and therefore be considered three different tax units.

[7] For a description of several policy options to raise significant revenue, see Steve Wamhoff and Mathew Gardner, “Progressive Revenue-Raising Options,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, February 5, 2019. https://itep.org/progressive-revenue-raising-options/

[8] Because this report analyzes the effects of proposals in 2020, many dollar amounts given are projections of what the inflation-adjusted amounts will likely be.

[9] The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act increased the CTC from $1,000 to $2,000 and made other changes. Like many other provisions in TCJA, the CTC changes will expire at the end of 2025 if Congress does not extend them.

[10] Aidan Davis, Meg Wiehe, Sophie Collyer, David Harris, Christopher Wimer, “The Case for Extending State-Level Child Tax Credits to Those Left Out: A 50-State Analysis,” April 17, 2019. https://itep.org/the-case-for-extending-state-level-child-tax-credits-to-those-left-out-a-50-state-analysis/

[11] Under current law, the refundable portion of the CTC is limited to 15 percent of earnings in excess of $2,500.

[12] This cap is inflation-adjusted annually but does not change in some years because the inflation-adjusted amount is rounded.

[13] The basic Rise Credit for single people (with or without children) is $4,050 in 2020, while the current EITC for single people with children can be larger than that. To prevent such families from losing benefits, the Rise Credit, which replaces the EITC, would include an additional component specifically for single parents with two or more children. It would be structured like a small EITC. For a single parent with two children, the additional component would equal 12.5 percent of earnings, up to $14,860 in earnings, for a maximum of $1,858 in 2020. For a single parent of three or more children, it would equal 18.75 percent of earnings, up to the same $14,860 of earnings, for a maximum of $2,786. This would be allowed in addition to the basic Rise Credit of $4,050 for single people and would be phased out similarly to the current EITC but over a longer income range. Under the Rise Credit, the Child Tax Credit would also continue to exist unchanged.

[14] Seniors with earnings could benefit from the provision in the Working Families Tax Relief Act that would raise the maximum age for the childless EITC from 64 to 67. Seniors with earnings could also benefit from the LIFT Act and Rise Credit. Seniors with dependent children could benefit from the expansion of the Child Tax Credit in the American Family Act and the Working Families Tax Relief Act.

[15] Working age here is defined as a tax unit in which neither the filer nor the spouse of the filer is age 65 years or older.

[16] See Misha Hill, Alan Essig, Meg Wiehe, Jenice Robinson, Steve Wamhoff and Carl Davis, “The Illusion of Race-Neutral Tax Policy,” February 14, 2019. https://itep.org/the-illusion-of-race-neutral-tax-policy/

[17] Meg Wiehe, Emanuel Nieves, Jeremie Greer, David Newville, “Race, Wealth and Taxes: How the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Supercharges the Racial Wealth Divide,” October 11, 2018. https://itep.org/race-wealth-and-taxes-how-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-supercharges-the-racial-wealth-divide/