Key Findings

- States can levy Wealth Proceeds Taxes based on the federal Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), which applies to the proceeds or profits generated by the wealth holdings of high-income households. The federal NIIT was implemented in 2013 to fund health care reforms and address disparities in the tax treatment of earned income from work versus passive proceeds derived from wealth. It applies to types of income that can only be generated from wealth such as interest, dividends, and capital gains, and it applies exclusively to high-income households.

- Most proceeds generated from wealth are tax-preferred at the federal level, facing effective rates roughly 40 percent lower than earned income. More than three quarters of the Wealth Proceeds Tax base proposed in this report is derived from long-term capital gains and qualified dividends, which are taxed at preferential federal rates ranging from 0 to 20 percent, while ordinary earned income is taxed at rates between 10 and 37 percent. Capital gains are also tax deferred, which provides an additional advantage over income from work. These disparities create inequities in the tax system as wealthier households see their income taxed much more lightly than individuals relying on wages.

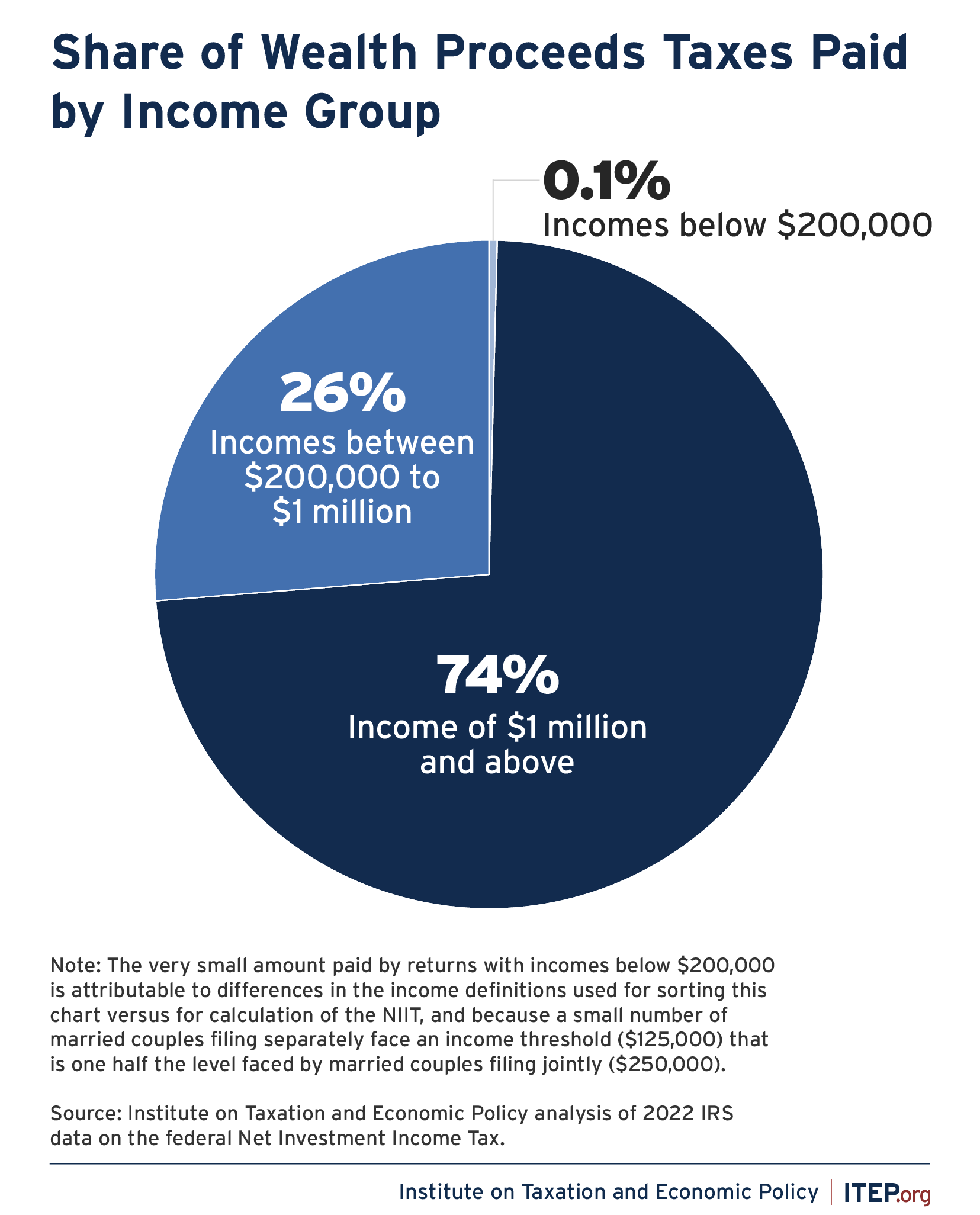

- Approximately three quarters of state Wealth Proceeds Taxes would fall on millionaires. Only 4.4 percent of taxpayers paid any amount of the applicable federal tax in 2022. Households with incomes under $250,000 for married couples or $200,000 for single filers do not pay this tax. Households with incomes over $1 million, on the other hand, account for 73 percent of all revenue collected by the federal tax.

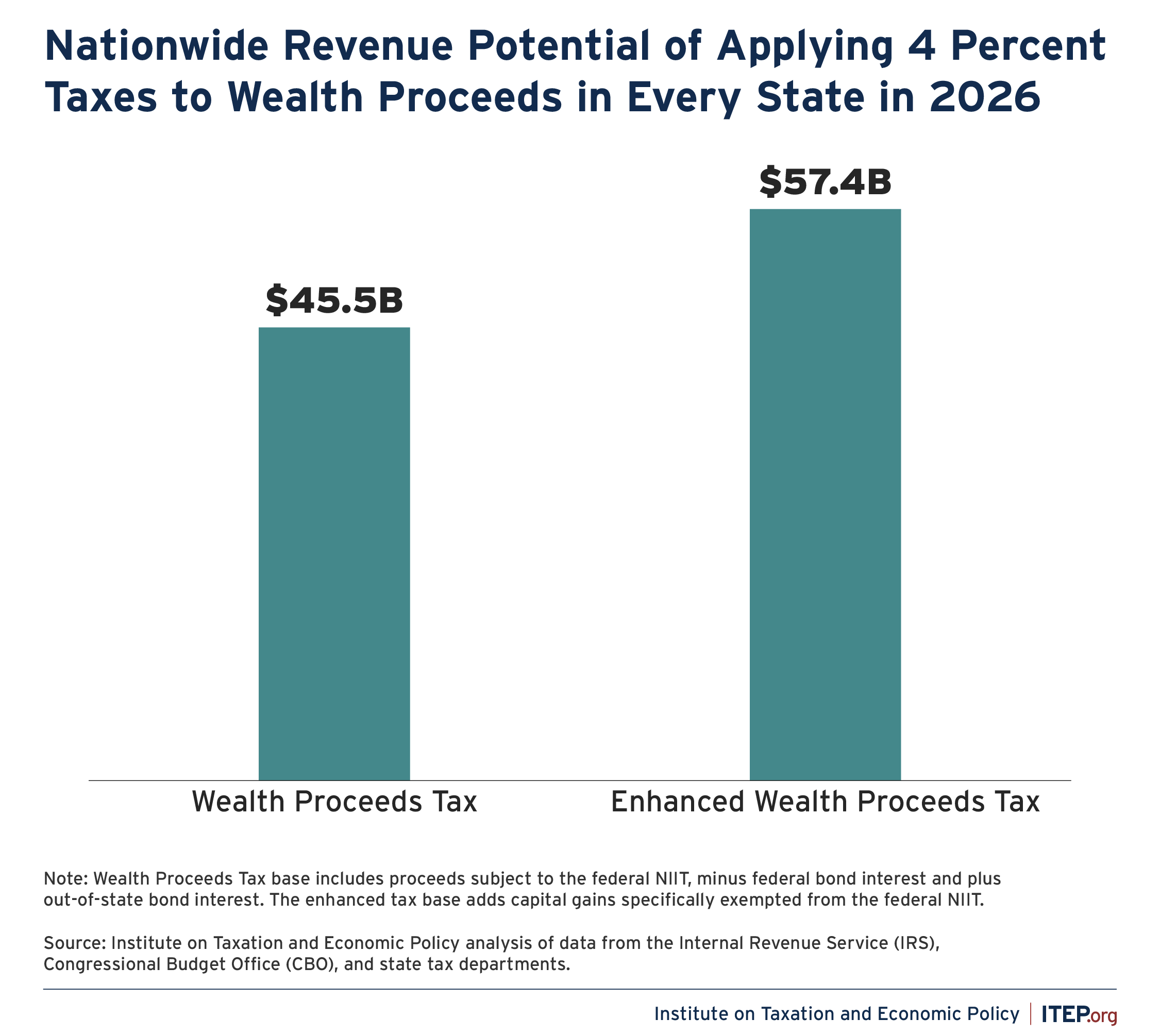

- State Wealth Proceeds Taxes could raise substantial revenue. Universal adoption of a modest 4 percent tax on wealth proceeds, for instance, would raise $45 billion for states in 2026 if they chose to structure their taxes to largely mirror federal rules. Under our preferred approach to create a more robust Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax, which makes one simple modification to more comprehensively tax high-income individuals’ capital gains, that same 4 percent rate would raise $57 billion a year.

- State Wealth Proceeds Taxes would be straightforward to administer for taxpayers and tax departments. States can use federal tax filings as the starting point for their Wealth Proceeds Taxes, reducing the need for complicated worksheets or for writing new definitions. In Minnesota, the first state to adopt such tax, the statute is just 223 words long and the form that taxpayers file with the state fits on a single page.

Overview

The federal tax code offers a shovel-ready definition of passive proceeds derived from wealth—such as capital gains, dividends, interest, and certain business profits—that states can use as the starting point for levying their own Wealth Proceeds Taxes on wealthy families.

These taxes have the potential to raise considerable revenue. If all states enacted a modest 4 percent Wealth Proceeds Tax, for instance, state revenues would rise by more than $45 billion a year. Under our preferred approach to apply that rate to an enhanced tax base that covers realized capital gains more comprehensively, state revenues would rise by more than $57 billion a year.

Background

The federal government has applied a 3.8 percent tax to the passive income —that is, the proceeds generated from wealth holdings — of high-income households since 2013. This tax, the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), is targeted toward wealthy households in two ways. First, it applies to types of income that can only be generated from wealth and that therefore disproportionately flow to the wealthiest households. And second, the tax applies only to income that exceeds a relatively high threshold.

The federal NIIT base is made up of passive wealth proceeds including capital gains, dividends, interest, and certain types of rent, royalty, business, and annuity income. The tax applies to married couples with income exceeding $250,000 and individuals with income exceeding $200,000, and only the portion of wealth proceeds that exceeds those income thresholds is subject to the tax. For example, an individual with $150,000 in salary income and $75,000 in capital gains would owe NIIT on just $25,000 of their capital gains.

The federal NIIT is a general fund revenue source that was enacted both to offset some of the cost of expanding access to health care and to advance parity in the taxation of wealth and work.1 States can create their own Wealth Proceeds Taxes, piggybacking on the federal NIIT, to fund their priorities and diversify their revenue streams to include more deliberate taxation of the wealthy.

Minnesota Enacts the Nation’s Most Comprehensive State Wealth Proceeds Tax

Minnesota became the first state to enact a law piggybacking on the federal NIIT in 2023.2 Minnesota’s levy assesses a 1 percent tax and applies only to the portion of wealth proceeds that exceed $1 million. We expect this tax to raise more than $60 million next year.

Other states also apply higher rates to certain types of proceeds generated from wealth. In Massachusetts, filers pay a tax rate on short-term capital gains that is 3.5 percentage points higher than the ordinary income tax rate.3 In 2025, Maryland enacted a 2 percent surcharge on both long-term and short-term capital gains for households with income over $350,000.4

The Case for a State Wealth Proceeds Tax

Economic inequality in the U.S. is large, growing, and highly unpopular. A large majority of Americans across the political spectrum are concerned about the rising gap between wealthy people and average Americans.5 Meanwhile, the U.S. tax code is failing to live up to its potential in addressing this urgent concern, and many aspects of the tax system are making inequality worse.

There is growing awareness, and frustration among many, that current federal and state tax laws are not well suited to taxing wealthy families in a way that genuinely reflects their ability to pay. This shifting understanding has been informed by a mix of careful economic analysis and reporting of leaked IRS data showing that wealthy families often pay exceptionally low tax rates when measured relative to a comprehensive measure of economic income.6

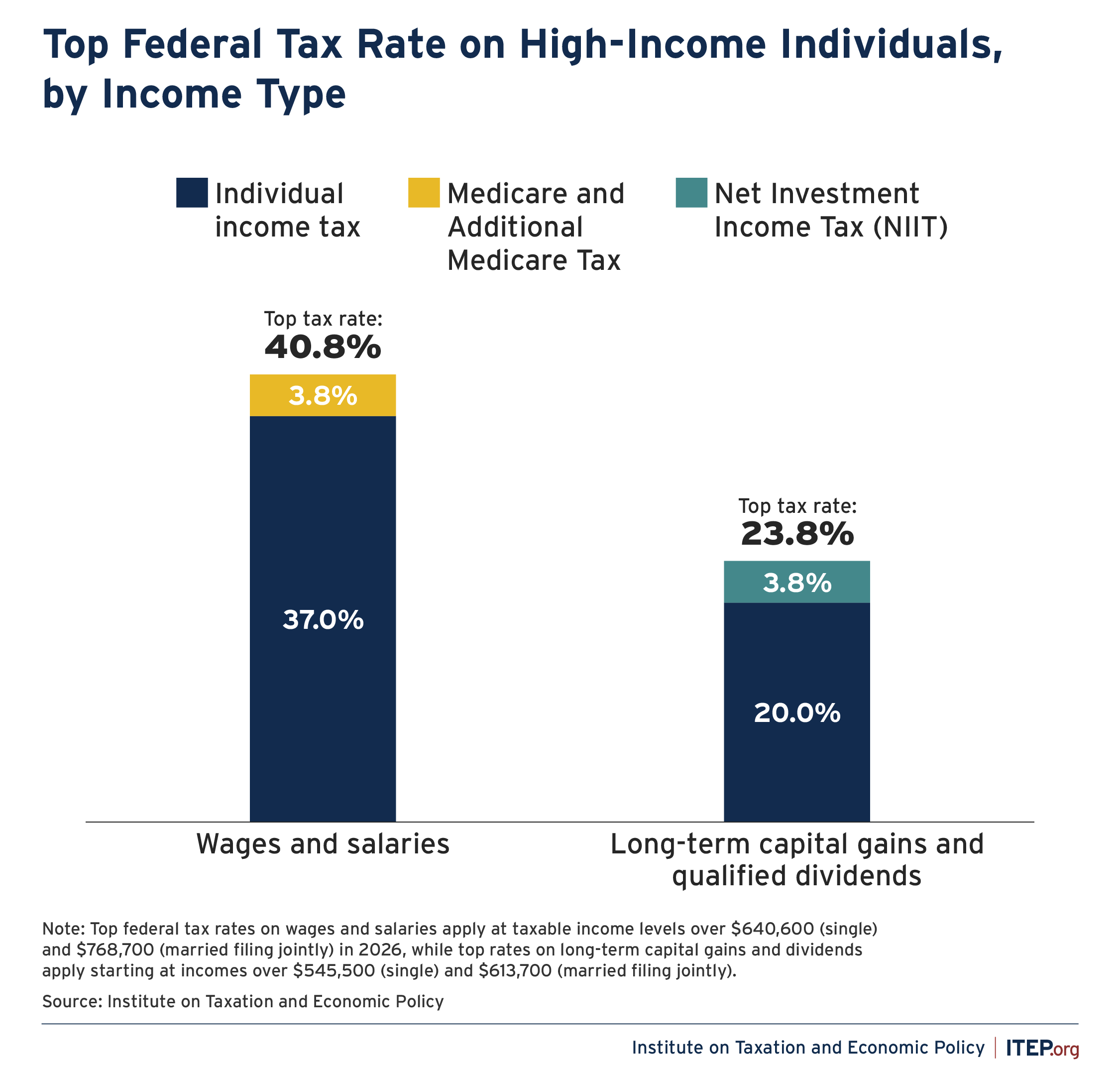

Part of the reason that wealthy families pay so little federal tax is that the passive forms of income created by their wealth are usually subject to much lower rates than earned income such as salaries and wages.7 Under federal law, regular income tax rates applying to workers span from 10 to 37 percent whereas long-term capital gains and qualified dividends enjoy preferential income tax rates of 0 to 20 percent. Some states also apply a lower income tax rate to certain wealth-related income, such as capital gains.8

Before 2013, the federal government’s Medicare payroll tax worsened the disparity in taxes on income from wealth and work by taxing earned income at 2.9 percent while entirely exempting unearned income derived from wealth. But the Affordable Care Act and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act largely resolved this imbalance in the context of federal health care taxes.9 Specifically, those bills boosted high-earners’ Medicare payroll tax rate to 3.8 percent and created a parallel structure—the NIIT—with an identical 3.8 percent rate on income derived from wealth.

As Figure 1 shows, the combined effect of these reforms is that high-income families face a top federal tax rate of 40.8 percent on their labor income while paying just 23.8 percent on most income generated by their wealth. Moreover, wealthy families typically pay comparatively little in Social Security and unemployment payroll taxes, as most of their labor income is exempt from these levies and unearned, passive income created by their wealth is exempt entirely.10

Figure 1

For state lawmakers concerned about under-taxation of the wealthy, Wealth Proceeds Taxes that piggyback on the federal NIIT offer a practical and effective path forward.

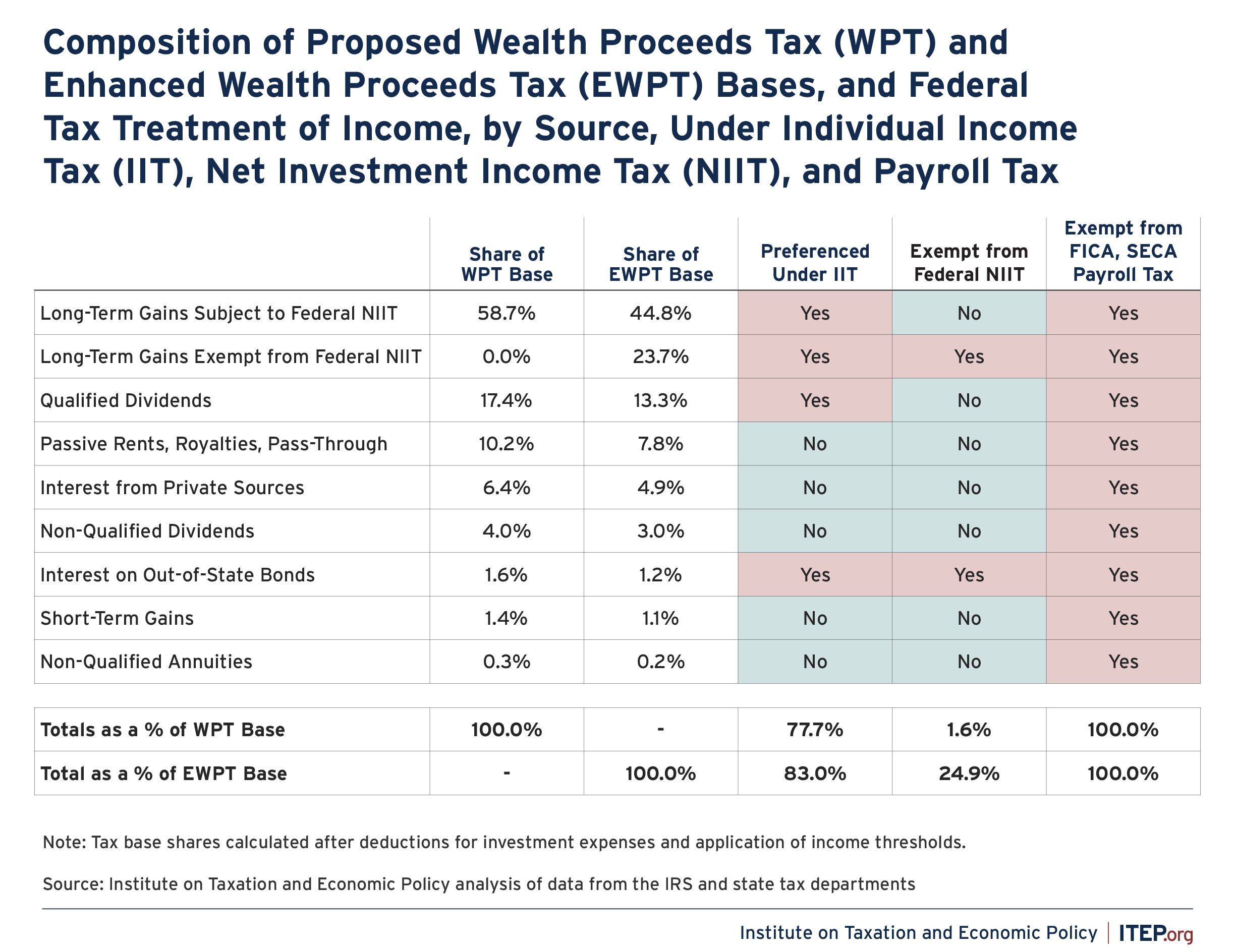

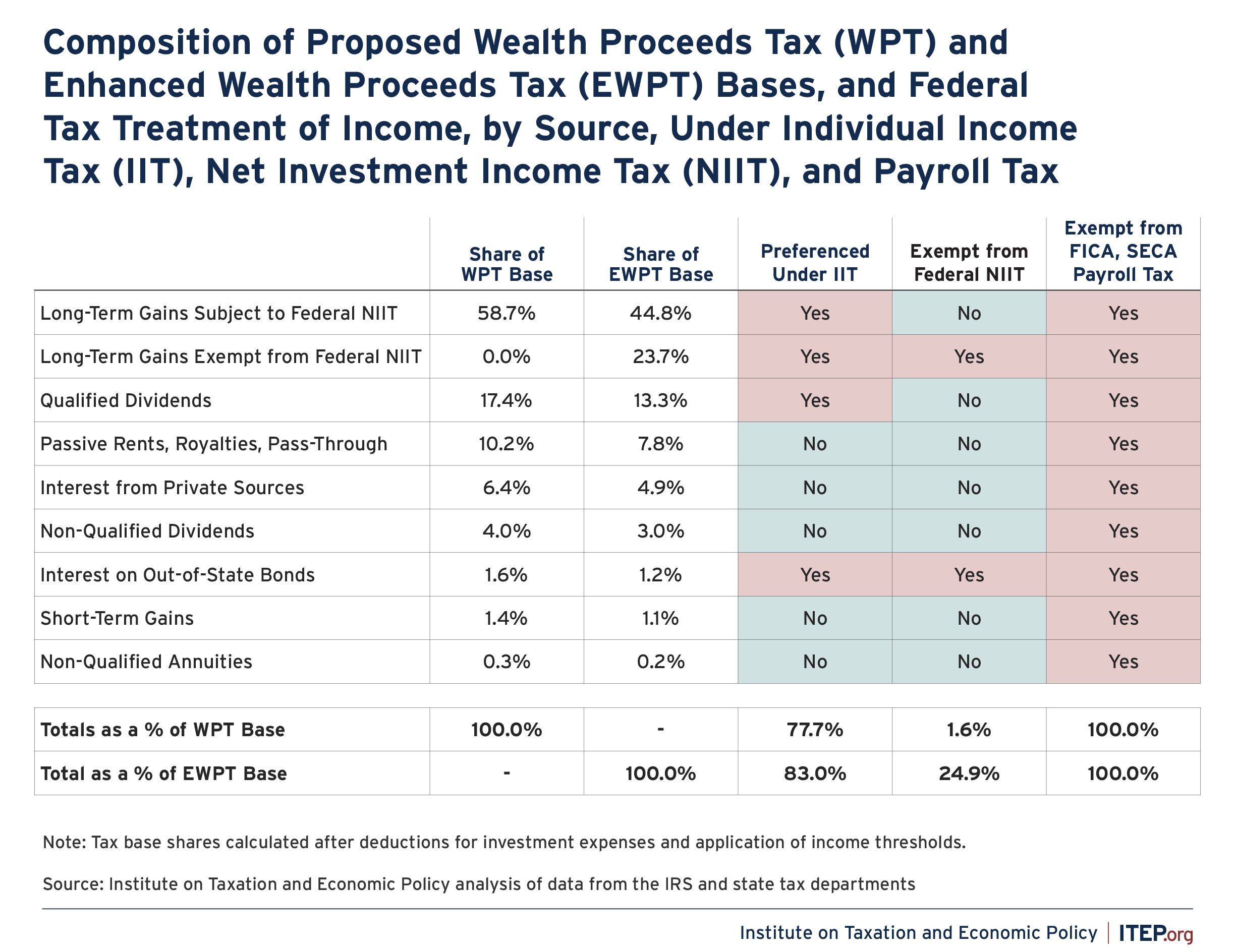

The federal definition of net investment income offers a simple way for states to identify proceeds derived from the ownership of wealth and make progress toward equalizing the tax treatment of those proceeds with how earned income is currently taxed. Nearly 78 percent of the tax base that would be subject to a Wealth Proceeds Tax is granted preferential treatment under the federal individual income tax. Under our preferred proposal for a more robust Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax, fully 83 percent of the tax base is granted special treatment under the federal income tax (see Appendix Table C.2).

A state Wealth Proceeds Tax would be simple to implement and would not require a large amount of administrative effort by taxpayers or state tax departments. Taxpayers potentially subject to the federal NIIT are already required to fill out a one-page federal tax form (Form 8960) calculating the amount of wealth proceeds subject to the NIIT, and the IRS is responsible for auditing those forms to ensure their accuracy.

Our recommended version of a state Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax would make just three simple adjustments to the amounts reported on that federal form:

- Subtract interest generated by U.S. federal bonds, as states are legally prohibited from taxing this interest. In states with income taxes, the filer will already know this amount as this subtraction already exists under state income tax law. This routine adjustment is a necessary part of adopting a state Wealth Proceeds Tax.

- Add interest generated by municipal bonds issued by other states or its localities. Again, in states with income taxes the filer is likely to already know this amount as states generally tax this interest.

- Add capital gains that are exempt from the federal NIIT but that the state wishes to include in its Wealth Proceeds Tax. Using the 2024 version of federal Form 8960 as the starting point, for example, the taxpayer would simply need to copy the amounts found on lines 5b and 5c to their state forms and add those amounts to their pool of taxable wealth proceeds. For states looking to tax realized capital gains even more comprehensively, federally excluded gains associated with so-called “Qualified Small Business Stock” could also be added to the base.11

While Minnesota’s state tax on wealth proceeds does not precisely follow this model, it does make a handful of adjustments to the federal NIIT base and, even so, its statute clocks in at just 223 words long. The relevant Minnesota tax form also fits onto a single page.12

Components of Wealth Proceeds

Wealth Proceeds Taxes would be tied to the federal definition of passive incomes subject to the federal NIIT. The federal tax code defines five major components of wealth proceeds subject to the NIIT: capital gains, dividends, interest, and annuities, along with certain kinds of rents, royalties, and business income.

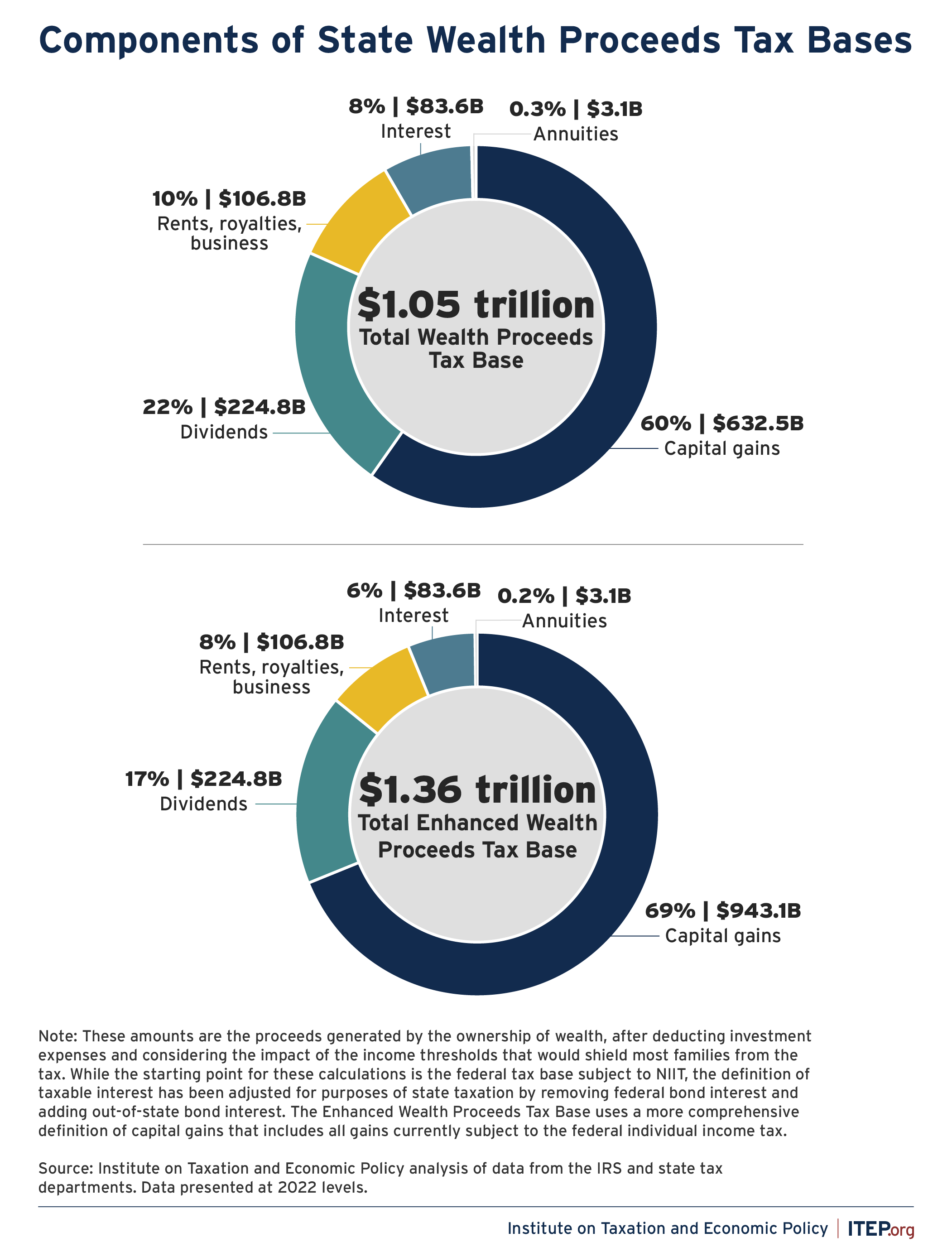

The bulk of these proceeds are made up of capital gains and dividends, which together comprise between 82 and 86 of the state tax bases proposed in this report, depending on which proposal is being examined (see Figure 2). The remainder is comprised of certain rents, royalties, and business income (8-10 percent of the base), interest (6-8 percent), and annuities (0.2-0.3 percent). Generally, these components are passive income sources and the tax base does not include income derived from active participation in a business or retirement income such as Social Security, pensions, 401(k)s, and IRAs.

This section describes the components of a Wealth Proceeds Tax base, and Appendix C offers a summary breakdown of the tax base and its current treatment under federal law.

Figure 2

Capital Gains

Capital gains are profits generated from the increase in value of assets such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and other property. Under a provision known as “deferral,” federal and state income tax on capital gains is paid only when an asset is sold. Thus, a stockholder who owns a stock over many years does not pay any tax as it increases in value each year. If the stock is sold during the investor’s lifetime, the “realized” capital gain is calculated by taking the difference between the original purchase price, or “basis,” and the sale price. Around two-thirds of capital gains are generated from the sale of corporate stocks.13

Most of the gains from the sale of a primary home would not be subject to a Wealth Proceeds Tax. Home sale profits (that is, increases in home value relative to what the owners paid for the home) up to $250,000 for single filers and $500,000 for joint filers are excluded from federal and state personal income taxes as well as the federal NIIT, and would be excluded from a state Wealth Proceeds Tax as well. Capital gains generated in tax-preferred retirement accounts such as 401(k)s and IRAs are also generally exempt.

While the federal NIIT includes most realized capital gains income in its base, it does allow for some sizeable exemptions of dubious merit that we propose including in the tax base of an Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax.

Most significantly, gains arising from certain sales of businesses or shares in a business partnership or pass-through entity are exempted from the federal NIIT if the seller actively participated in the business. Because wealthy individuals receive much higher returns on their business sales than the average business owner, this exemption is likely to be particularly skewed toward the wealthiest families.14 In one instance, this carveout allowed the owner of a sports team to avoid the NIIT on roughly $2 billion in gains generated by the sale of that team.15 In addition to avoiding the federal NIIT, many of the gains in question are also subject to preferential capital gains rates under the federal individual income tax that are significantly lower than the tax rates on wages—a fact that strengthens the case for including those gains in the base of a state Wealth Proceeds Tax.

Separately, a significant amount of capital gains associated with the sale of so-called Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) is exempted from both the federal individual income tax and the federal NIIT. Despite being billed as a benefit for “small businesses,” this arcane provision of federal law is inaccessible to most of the general public and tends to be used most heavily by venture capitalists. Roughly 94 percent of gains excluded from tax by the QSBS provision flow to households with annual incomes over $1 million per year.16 It would be straightforward for states to add these QSBS gains to the base of their Wealth Proceeds Taxes.

Capital gains are divided into short-term and long-term gains for tax purposes. Short-term gains are those derived from assets held for less than one year and are taxed at the same ordinary federal income tax rates as salaries and wages. Our analysis of IRS data suggests that just 2.4 percent of capital gains subject to NIIT are short-term in nature. The other 97.6 percent are long-term gains on assets held for one year or more. These long-term gains are subject to a top federal income tax rate of just 23.8 percent, including the basic 20 percent federal personal income tax and the 3.8 federal NIIT. This is 17 percentage points lower than the federal income tax rate that applies to salary and wage income, as seen earlier in Figure 1.

Dividends

Dividends are business profits distributed to the shareholders of that business. More than four in five dividend dollars flowing to federal NIIT filers are subject to preferential federal income tax rates.17These dividends, known as qualified dividends, are those associated with stock holdings that the filer owned for at least 61 days of the 120-day period surrounding the date of the dividend payout.

Less than one in five dollars of NIIT filers’ dividend income is associated with stock held for 60 days or fewer, and these dividends are taxed as ordinary income.

Both qualified and non-qualified dividends are subject to the federal NIIT and would be taxed under a state Wealth Proceeds Tax. The qualified dividends that account for the bulk of all dividends flowing to NIIT filers are taxed by the federal government at a maximum rate of just 23.8 percent, including the preferential 20 percent federal personal income tax and the 3.8 percent federal NIIT. Just as with long-term capital gains, this rate is 17 percentage points lower than the federal income tax rate that applies to salary and wage income.

Rents, Royalties, Partnerships, S Corporations, and Trusts

The federal NIIT base includes a variety of income sources from passive business involvement. For each of these income types, the income is excluded for filers who can show they materially participated in the business that produced the income. What remains are the passive proceeds created by asset ownership, including:

- Rental income from real estate properties

- Royalty income from the authorized use of property such as copyrights, patents, or mineral rights

- Income from passive ownership in partnerships and S corporations

- Income from trusts

Business owners do not owe federal NIIT on their active business income because the intent of the NIIT is not to tax the income derived directly from the work that a business owner puts into their business. To screen out active business income, the IRS uses a test of “material participation” that can be established under several criteria, but the most common test is whether the filer spent at least 500 hours, or roughly 10 hours per week, working on the business in the given tax year.18 This generous test ensures that even business owners who are only working at their business in a very part-time capacity are not paying NIIT on their business income. This income would also be exempted from a state Wealth Proceeds Tax.

Taxable Interest

Most interest payments received from bank accounts, as well as savings instruments such as Treasury and corporate bonds and Certificates of Deposit, are taxable income. Interest generated by these savings vehicles is taxed as ordinary income at the federal level and is also subject to the NIIT.

Adapting the federal NIIT to state tax purposes requires at least one adjustment to the taxation of interest. While the federal NIIT applies to federal bond interest, states are legally prohibited from taxing federal bond interest and states must therefore carve out this interest from their Wealth Proceeds Taxes.19

On the other hand, the federal government does not tax state and local bond interest under the individual income tax or the NIIT. As a result, a state that chooses to use the federal NIIT as the starting point for its Wealth Proceeds Tax will automatically exempt this form of interest unless it chooses to selectively decouple from the exemption. A state exemption may be prudent in the context of bonds issued by that state or its localities, but there is little reason for a state to exempt interest paid on bonds issued by other states and their localities. Most states already tax out-of-state bond interest under their individual income taxes and would presumably wish to also do so under a state Wealth Proceeds Tax.

Our analysis of data reported by state revenue agencies indicates that modifying the federal NIIT base to remove federal bond interest but add out-of-state bond interest would slightly expand the taxable base overall and increase the revenue yield of a Wealth Proceeds Tax. The revenue estimates contained in this report reflect these modifications.

Non-Qualified Annuities

Annuities are investment products that individuals or their employers pay into upfront. In return, individuals receive guaranteed payments later in life or upon the individual’s death. For tax purposes, annuities are broken into two categories: qualified and non-qualified.

Most annuities are qualified annuities, meaning three things. First, they are subject to an annual limit on the amount individuals can contribute toward the annuity each year. Second, they are funded with pre-tax dollars, meaning the income used to fund the annuity is not taxed in the year it is contributed and instead owners pay taxes on the annuity income when it is distributed later in life. And third, once an individual reaches age 73, they are required to draw down minimum distributions from the account.

Non-qualified annuities, on the other hand, are paid for with after-tax income and allow for unlimited contributions. Once the annuity begins to pay out, individuals owe tax on the portion of the payout that exceeds their initial contribution. For example, if someone invested $1 million in a non-qualified annuity but is expected to eventually receive $1.5 million in payouts from that annuity, then two-thirds of every dollar paid out would be a considered a tax-exempt withdrawal of their initial investment.20

Only non-qualified annuity income is subject to the federal NIIT. A state Wealth Proceeds Tax would apply to these annuities.

Wealth Proceeds Tax Effects by Income Level and Race

State Wealth Proceeds Taxes would affect a relatively small number of affluent households. Just 4.4 percent of people filing federal tax returns in 2022 owed any NIIT, and very high-income people contributed the bulk of the tax dollars collected under this tax.

According to the IRS, almost three-quarters (73 percent) of all federal NIIT payments in 2022 came from the highest-income 0.5 percent of filers, or those with incomes over $1 million.21 An even more detailed breakdown of NIIT liability by income level is available from the IRS for 2019, and it shows that a third of the NIIT was paid by the top 0.01 percent of households by income, or those with income over $10 million.22

Figure 3

While IRS data do not allow for examination by wealth level, the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances underscores that the wealth that generates passive income is highly concentrated. In 2022, the wealthiest 10 percent of households received 44.7 percent of pre-tax income and controlled 73 percent of all wealth. Meanwhile, the top 1 percent captured 15 percent of all income and held 35 percent of the nation’s wealth. Because the NIIT applies exclusively to proceeds generated from wealth, it is clear that ultrawealthy families are paying a large share of this tax.

The concentration of wealth is more pronounced than income in part because of the multigenerational nature of wealth accumulation. Recent estimates suggest that more than a third of all wealth owned in the U.S. was acquired through inheritance.23 Because inheritance represents the transfer of wealth from one generation to another, it tends to solidify inequality and reduce opportunity by imposing the wealth inequality of the previous generation on the current generation.24

Estate taxes on very large wealth transfers have historically helped curb this entrenchment of intergenerational inequality, but aggressive tax avoidance and repeated cuts to these levies by federal and state lawmakers have greatly reduced their effectiveness in this regard.25

As a result, large inheritances are tending to lock in historical policy and economic realities, many of which stood in the way of allowing historically marginalized populations to build wealth.26 As evidence of this, consider that ownership of corporate stocks in ordinary taxable accounts—which is responsible for generating most of the income included in the federal NIIT base—is highly concentrated among white Americans.27Eighty two percent of stock held by people with incomes high enough to be subject to the NIIT is held by white families, even though white families make up just 67 percent of households overall.28

Revenue Potential of State Wealth Proceeds Taxes

Wealth Proceeds Taxes have significant revenue potential for states.

Appendix Table A.1 presents state-by-state estimates of the revenue potential of levying a Wealth Proceeds Tax in its simplest form, with a single rate applied to a tax base that closely resembles federal rules (that is, federal net investment income minus federal bond interest but including out-of-state bond interest). Applying a 4 percent tax to this base in all states could raise more than $45 billion in new revenues a year.

Higher rates could also be considered, especially in states that have no income tax, low-rate income taxes, flat income taxes, or preferential treatment of capital gains. Applying a higher rate would do more to equalize the tax treatment of earned and unearned income. The top federal income tax rate on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends is 17 percentage points lower than the top federal income tax rate on salaries and wages—and capital gains and dividends are exempt from federal payroll taxes that fund Social Security and unemployment insurance as well.

Figure 4

For states interested in a more robust and comprehensive tax on proceeds generated from wealth, we also examine a proposal for an Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax in Appendix Table A.2. Among high-income families filling the relevant NIIT forms, current federal rules exempt roughly one-third of their realized capital gains income from the NIIT. For instance, gains derived from selling a business in which the owner actively participated are exempt from the federal NIIT. A state Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax would discard this exemption in favor of a more robust and comprehensive tax base that captures all capital gains currently subject to the federal individual income tax.

Rolling these capital gains back into the tax base would boost the revenue-raising potential of taxing wealth proceeds at the state level. Applying the same 4 percent tax rate to this enhanced definition of wealth proceeds would yield more than $57 billion a year across all states, or 26 percent more than what could be raised by the narrower tax tied more closely to federal law. Such a tax would also be less prone to aggressive tax avoidance or evasion, as wealthy people could no longer seek to sidestep the tax by claiming to have actively participated in the businesses they are selling.

The methodology underlying these calculations is described in Appendix D.

Revenue Stability of Wealth Proceeds Taxes

States considering adopting Wealth Proceeds Taxes may wish to consider the stability of the revenue stream generated by those taxes. This tax base will fluctuate over time due to changes in the economy and decisions investors make regarding whether to sell or hold assets.

While the revenue potential of a state Wealth Proceeds Tax is substantial, it would still represent only a small fraction of state budgets, meaning that swings would not meaningfully threaten the stability of state general fund revenues.29

If policymakers intend to earmark Wealth Proceeds Tax revenue to a specific program, on the other hand, careful planning is warranted to ensure the funds are allocated sustainably. One possible approach is to limit spending from such a fund to 90 percent of the average revenue collected by the tax over the past five years.30 Historical data on the last decade of federal NIIT collections show that such a condition would have resulted in sustainable funding streams in every state except for Arkansas, which appears to be an outlier in its volatility level because of its unusually high concentration of wealth in the hands of a small number of extraordinarily wealthy people.31

Protecting Wealth Proceeds Taxes from Tax-Avoiding Trusts

It is no secret that high-income and wealthy individuals often employ tax accountants and lawyers to help them avoid paying taxes in ways that circumvent the spirit of the law. Tax avoidance is an issue affecting virtually every tax in existence, and the Wealth Proceeds Tax is no exception.

Of particular concern are trusts established with the purpose of shifting wealth proceeds, on paper, into low-tax states. Incomplete non-grantor trusts (ING trusts), for example, are often used with this purpose in mind and have attracted significant scrutiny from state tax authorities in recent years.

Fortunately, California and New York have shown that this problem can be fixed by treating ING trusts as grantor trusts instead. In short, these states assign the income of the trust to the grantor—or the person who created the trust—rather than to the trust itself.32 The effect is to tax the person based on where they actually live, rather than attempt the futile task of taxing a trust housed in a tax haven state such as Delaware, Nevada, South Dakota, or Wyoming.

States can also promote greater stability in their Wealth Proceeds Taxes by taking care not to design them with direct, active linkages to federal law. The federal NIIT has proven to be a durable reform, having been in effect for nearly 12 years as of this writing. But there is always a risk that a future Congress could chip away at the NIIT base or repeal the tax entirely. To safeguard against this outcome, states can use what is known as “fixed date” conformity under which they link their tax rules to the federal tax code as it exists on a certain fixed date. Under this approach, which many states already use in their income tax codes, if Congress decides to change the NIIT, the changes will not affect state Wealth Proceeds Taxes unless and until state lawmakers review the federal change and vote to adopt it in their state tax code by updating their conformity date.33 The result is that states can retain most of the simplicity benefits of federal conformity without putting their tax laws on an autopilot system that is vulnerable to disruption by Congress.

Conclusion

State Wealth Proceeds Taxes are a clear opportunity to generate substantial revenue by diversifying state tax systems with a measure tailormade to ask more of the wealthy. The simplicity of administering Wealth Proceeds Taxes based on federal filings, along with the promise of increased parity in the treatment of earned and passive income, make this an attractive option for states. By enacting their own Wealth Proceeds Taxes, states can advance more equitable taxation of wealth relative to work, reduce income and wealth inequality, and secure funding for essential programs.

Note: This report was updated in January 2026 to reflect revisions to revenue estimates in Alabama and Ohio, which in turn slightly affected the national results.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix Table C.1

Appendix Table C.2

Appendix D: Revenue Estimation Methodology

The starting point for the revenue calculations performed for this report is the amount of federal Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) paid by each state’s residents in 2022, as reported in IRS Historic Table 2 (HT2). Dividing that figure by 3.8 percent yields the amount of Taxable Net Investment Income (TNII) received by each state’s residents that year—defined here as Total Investment Income (TII) minus deductible investment expenses and income exempted by the NIIT’s income thresholds. TNII by state is an important target used in our revenue calculations.

To estimate the revenue potential of state Wealth Proceeds Taxes, it is necessary to disaggregate TNII into its various components because capital gains realizations are somewhat responsive to changes in tax rates. In other words, the size of this component of the tax base depends in part on the rate of the Wealth Proceeds Tax being analyzed.

We separate the portion of the tax base comprised of capital gains from the rest of the base using a method that allows us to account for the fact that capital gains make up a larger share of high-income tax units’ income in some states than in others. Specifically, we first examine the relevant sources of income in HT2, by state, flowing to tax units with Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) of $200,000 or more per year. These are the tax units most likely to be impacted by the NIIT and they account for 99.9 percent of all federal NIIT revenues. Each income source from HT2 is then scaled using a ratio derived by comparing the IRS line item estimates for Form 8960 to the HT2 data to determine the expected share of each income source that will appear in TII. For instance, most income from rent, royalty, partnership, and S corporation profits is not derived from a passive activity and thus is not included in TII. Our analysis reveals that, for tax units with AGI above $200,000 per year, just 11 percent of the total income derived from these sources is included in TII.

After deriving this preliminary estimate of the composition of TII in each state we must make two adjustments to whittle this income definition down to the narrower TNII category actually subject to tax. The first adjustment involves deducting relatively minor amounts of investment expenses from the rent, royalty, partnership, S corporation, and capital gains categories, which we do in proportion to the share of each of those income sources included in TII. The second adjustment is more complex and involves estimating the ways in which the federal NIIT’s income thresholds are shielding various forms of TII from tax.

Our review of the IRS line item estimates indicates that 13 percent of TII, net of investment expenses, received by Form 8960 filers is ultimately exempted because of the NIIT’s income thresholds. Among tax units receiving incomes high enough to file Form 8960, the thresholds are most beneficial to tax units whose incomes are derived almost entirely from passive sources included in TII. A single filer with $200,000 or more of salary or active business income, for example, derives no benefit from the thresholds and sees the entirety of their TII subject to tax. On the other hand, a single filer who does not earn a salary or generate active business income, and whose entire income is comprised of TII, can exclude the first $200,000 of their TII from tax. Because tax units living primarily or solely off passive investment income can be found at various points throughout the top of the income scale, we distribute the total tax savings associated with the income thresholds (as measured in the IRS line item report) to each income band, in each state, in accordance with the number of federal NIIT returns found in that band. In doing so we take into account the ways in which income composition varies by band to determine the degree to which various categories of TII are excluded from TNII as a result of the income thresholds.

At this point we have a preliminary estimate of TNII, by income source, for each state and nationally that we can compare to the more authoritative TNII target described at the outset of this methodological writeup. While the preliminary estimate is on target nationally, it deviates somewhat from the target in each state which is unsurprising because the share of business and capital gains income that is passive and thus potentially includable in TII varies across states. We now take this variation into consideration by adding or subtracting the amount of income needed to bring us in line with our state-by-state targets. Those adjustments are made entirely from the business and capital gains income categories and are done in proportion to those sources’ relative importance to the income composition of tax units with AGI above $200,000.

The result of the work up to this point is an estimate of TNII by source that matches the authoritative TNII aggregate targets, by state, derived from HT2 for 2022. We then make two slight adjustments to adapt these estimates for state tax purposes. First, we use state tax expenditure report data in conjunction with HT2 to estimate the amount of taxable interest income associated with federal government bond interest and we remove this income from the state Wealth Proceeds Tax base because 31 U.S. Code § 3124 prohibits states from taxing this income. Second, we again use state tax expenditure report data along with HT2 to estimate the share of federally tax exempt interest that each state’s residents derive from their investments in out-of-state bonds, and we add this income to the base in expectation of the fact that states are likely to include this income in their Wealth Proceeds Tax bases just as they already typically include it in their personal income tax bases.

With 2022 estimates of the Wealth Proceeds Tax base, by state, now in hand we age those amounts to 2026 levels using the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecast for growth in federal NIIT collections from 2022 to 2026.

Calculating the revenue yield of a Wealth Proceeds Tax on income sources other than capital gains is then a straightforward exercise of multiplying that portion of the tax base by the applicable tax rate. For realized capital gains the calculation is considerably more complicated, as increases in the tax rate on realized gains cause investors to reduce the extent to which they sell appreciated assets, thereby reducing the size of the applicable tax base.

We estimate that behavioral response using an equation preferred by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) to adjust capital gains realizations based on the elasticity response to rate changes.34 The equation takes into account current combined federal, state, and local capital gains tax rates in each state, which we obtain by reviewing state tax forms and recently enacted legislation. It also requires the use of a realization coefficient, which we take to be 2.28—representing a balance among the range of estimated coefficients found in the credible economic literature reviewed by CRS. Although our estimates provide useful guideposts, we note that there may be features of specific state tax systems that have not been fully accounted for in this analysis.

We have now estimated the level of capital gains realizations under various levels of state Wealth Proceeds Tax rates. Multiplying those realizations by the applicable state rate yields the expected revenue gain from subjecting those gains to a new state Wealth Proceeds Tax. And adding the more straightforward non-capital gains revenues mentioned above to that total yields the grand total revenue estimates found in Appendix Table A.1. The revenue gain estimates presented in that table are reported net of any reduction in state and local personal income tax revenue resulting from changes in capital gains realization levels.

As a supplement to our analysis, we also present estimates for a more expansive policy proposal in Appendix Table A.2, which we call an Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax. This tax would include all the same income components as the Wealth Proceeds Tax analyzed in Appendix Table A.1, plus capital gains that are subject to federal individual income tax but specifically exempted from the federal NIIT, such as those derived from the sale of company stock in an employer-sponsored retirement plan or from a business in which the owner actively participated. (One could imagine an even more expansive version of the tax that also included federally exempt gains such as those derived from Qualified Small Business Stock, or QSBS, though we do not quantify the revenue potential of that more expansive version in this report.35) The IRS line item estimates reveal that around 35 percent of capital gains reported by filers of Form 8960 are exempted from TII.

We then adapt the analytic framework that we used to estimate the amount of capital gains included in the basic Wealth Proceeds Tax base to the task of estimating the amount included in our Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax base. That is, we estimate the state-by-state impact of adding gains that are exempted from the federal definition of TII to the base of our proposed Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax.

The amount of gains exempted from the basic Wealth Proceeds Tax is estimated by starting from total capital gains flowing to tax units with $200,000 or more of AGI, making relatively modest adjustments to remove certain investment expenses and income shielded by the federal NIIT’s income thresholds, and then subtracting gains previously estimated to be included in the base of the basic Wealth Proceeds Tax. The result is a value for gains exempt from the federal NIIT, by state, that is then aged from 2022 to 2026 levels using the CBO’s forecast for growth in realized capital gains income between these years. The revenue yield of taxing this broader base under an Enhanced Wealth Proceeds Tax is calculated in the same manner as described above for the basic Wealth Proceeds Tax, with separate estimation techniques employed for realized capital gains versus other sources of income generated from owning wealth.

Endnotes

- 1. McClelland, Robert, Bowen Garrett, Eugene Steuerle, and Gordon Mermin (2025). “Net Investment Income Tax: A Primer.” Urban Institute.

- 2. 2024 Minnesota Statutes, Section 290.033. “Net Investment Income Tax.” Accessed October 2025 at: https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/290.033

- 3. Massachusetts Department of Revenue. Massachusetts tax rates. Accessed October 2025. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massachusetts-tax-rates.

- 4. Maryland Statute section 10-105 a (3). Accessed October 2025 at: https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Laws/StatuteText?article=gtg§ion=10-105&enactments=true.

- 5. Young, Clifford and Bernard Mendez (2025). “How Americans Feel About the U.S.’ Rising Income Inequality.” Ipsos.

- 6. Yagan, Danny (2023). “What is the average federal individual income tax rate on the wealthiest Americans?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 39 (3), 438-450. Eisinger, Jesse, Jeff Ernsthausen, and Paul Kiel. “The Secret IRS Files: Trove of Never-Before-Seen Records Reveal How the Wealthiest Avoid Income Tax.” ProPublica. June 8, 2021. Kiel, Paul, Ash Ngu, Jesse Eisinger, and Jeff Ernsthausen. “America’s Highest Earners and Their Taxes Revealed.” ProPublica. April 13, 2022.

- 7. Other provisions such as deferral and stepped-up basis also play a role.

- 8. Ten states offer broad carveouts for capital gains (Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaiʻi, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin) while several others offer more narrowly tailored preferences exclusively for gains generated by certain assets located within their borders.

- 9. Both pieces of legislation were enacted in 2010 and their tax changes took effect starting in 2013.

- 10. In 2025, workers and their employers each pay 6.2 percent in Social Security tax on income up to $176,000. For federal unemployment taxes, employers owe 0.6 percent tax on the first $7,000 in wages paid. As a result, high-income earners typically pay Social Security and unemployment taxes on just a fraction of their overall labor income.

- 11. Austin, Sarah and Nick Johnson (2025). “Quite Some BS: Expanded ‘QSBS’ Giveaway in Trump Tax Law Threatens State Revenues and Enriches the Wealthy.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

- 12. 2024 Minnesota Statutes, Section 290.033. “Net Investment Income Tax.” Accessed October 2025 at: https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/290.033. Minnesota Department of Revenue. “2024 Schedule NIIT, Net Investment Income Tax.”

- 13. IRS. Table 1A. Short-Term and Long-Term Capital Gains and Losses, by Asset Type, Tax Year 2015.

- 14. As the Washington Center for Equitable Growth explains: “Richer individuals own businesses that sell for higher multiples: the average S-corp Enterprise Value (EV) to EBITDA ratio for the top 1% is 9.0, compared to 5.8 for the middle 40; for partnerships, the top 1% EV/EBITDA is 8.6 compared to 5.9 for the middle 40.” Campbell, Cole, Jacob A. Robbins, and Sam Wylde (2025). “The distribution of capital gains in the United States.” Washington Center for Equitable Growth Working Paper Series.

- 15. Kiel, Paul. “How Billionaires Have Sidestepped a Tax Aimed at the Rich.” ProPublica. December 18, 2024.

- 16. See note 11.

- 17. Analysis of the 2015 IRS Public Use File by ITEP Senior Data Analyst Emma Sifre indicates that qualified dividends account for 81.5 percent of all dividends flowing to NIIT filers.

- 18. Internal Revenue Service (2023). “Publication 925 – Passive Activity and At-Risk Rules.”

- 19. 31 U.S. Code § 3124.

- 20. IRS Publication 939 offers a helpful overview of how this “exclusion ratio” is calculated. It is currently available online at: https://www.irs.gov/Pub939

- 21. IRS. Historic Table 2. Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2022.

- 22. IRS. Table 3.3. All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2019 (Filing Year 2020).

- 23. The estimates of inherited wealth as a percent of all wealth are 35-45 percent, 43 percent, 20-25 percent, 19 percent, and 60 percent from the following sources, respectively: Davies, James B. and Anthony F. Shorrocks. “The Distribution of Wealth,” in A.B. Atkinson and F. Bourguignon (eds.) Handbook of Income Distribution. North-Holland: Elsevier (1999): 605-75. Available at: https://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/course/Davies,Shorrocks(2000).pdf DeLong, Bradford J. “A History of Bequests in the United States,” in Alicia Munnell & Annika Sunden (eds.) Death and Dollars: The Role of Gifts and Bequests in America. Brookings Institution Press (2004): 33-63; Brown, Jeffrey R. and Scott J. Weisbenner, “Intergenerational Transfers and Savings Behavior,” In David A. Wise (ed.) Perspectives on the Economics of Aging, University of Chicago Press (2004): 181-203; Wolff, Edward N. and Maury Gittleman, “Inheritances and the Distribution of Wealth or Whatever Happened to the Great Inheritance Boom?,” Journal of Economic Inequality 12(4) (2014): 439-68; Piketty, Thomas and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth and Inheritance in the Long Run,” in A.B. Atkinson and F. Bourguignon (eds.) Handbook of Income Distribution Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2015): 1303-68.

- 24. Researchers find between 5 and 14 percent of the Black-White wealth gap is explained by inheritance. McKernan, Singe-Mary, Caroline Ratcliffe, Margaret Simms, and Sisi Zhang (2012). “Do Financial Support and Inheritance Contribute to the Racial Wealth Gap?” Urban Institute. Shapiro, Thomas, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro. (2013). “The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide.” Institute on Assets and Social Policy. Sabelhaus, John and Jeffrey P. Thompson (2023). “The Limited Role of Intergenerational Transfers for Understanding Racial Wealth Disparities.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Current Policy Perspectives.

- 25. Steverman, Ben, Anders Melin, Devon Pendleton, and Chris Nosenzo. “The Hidden Ways the Ultrarich Pass Wealth to Their Heirs Tax-Free.” Bloomberg Businessweek. October 21, 2021. Simani, Ellis, Robert Faturechi, and Ken Ward Jr. “How These Ultrawealthy Politicians Avoided Paying Taxes.” ProPublica. November 4, 2021.

- 26. McKay, Lisa Camner (2022). “How the racial wealth gap has evolved and why it persists.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Maye, Adewale A. (2023). “Chasing the dream of equity.” Economic Policy Institute.

- 27. Stock ownership accounts for two thirds of capital gains according to the IRS and is the primary driver of dividends payments. Dividends and capital gains made up more than 80 percent of federal net investment income in 2022 according to the IRS. Taken together, these findings suggest stock ownership generates the majority of federal net investment income.

- 28. Analysis of the Federal Reserve Board’s 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances by ITEP Senior Data Analyst Emma Sifre. Comparable figures (stock holdings share / household share) are: Black (0.5 percent / 11.5 percent), Hispanic (0.5 percent / 9.4 percent), Asian (15.5 percent / 3.9 percent), and multiracial or other race (1.2 percent / 8.4 percent).

- 29. At rates of 1 or 2 percent, revenues would be less than 5 percent of own-source revenues for all states. Only Florida would see its Wealth Proceeds Tax revenues exceed 5 percent of state revenues with a tax rate of 3 percent, and only Florida and Wyoming would meet this threshold when applying tax rates of 4 or 5 percent. This calculation compares the revenue estimates presented in Appendix Table A.1 to U.S. Census Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances data of own source revenues for 2022, inflated to 2026 dollars using national GDP projections from the Congressional Budget Office.

- 30. For the first five years following implementation, before a sufficient track record of revenue collections is established, these amounts could be estimated using federal and state tax filings from prior years.

- 31. Davis, Carl, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini (2022). “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Swaim, Kyler. “Eight Billionaires with Arkansas Ties Make Forbes List of Richest Americans.” Northwest Arkansas Homepage. October 8, 2024.

- 32. Griswold, Don and Michael Mazerov (2023). “States Should Follow New York’s Lead and Shut Down Tax-Avoiding ‘ING Trusts.’” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- 33. The Federation of Tax Administrators provides a list of conformity practices by state, as of January 2023, available at: https://taxadmin.org/wp-content/uploads/resources/tax_rates/stg_pts.pdf

- 34. Gravelle, Jane (2021). “Capital Gains Tax Options: Behavioral Responses and Revenues.” Congressional Research Service.

- 35. See note 11 for ITEP’s examination of the impact of the QSBS exemption in the states.