Who Pays?

Minnesota stands apart from the rest of the country with a moderately progressive tax system that asks slightly more of the rich than of low- and middle-income families. Recent reforms signed by Gov. Tim Walz have contributed to this reality.

There are a variety of factors that affect teacher pay. But one often overlooked factor is progressive tax policies that allow states to raise and provide the funding educators and their students deserve.

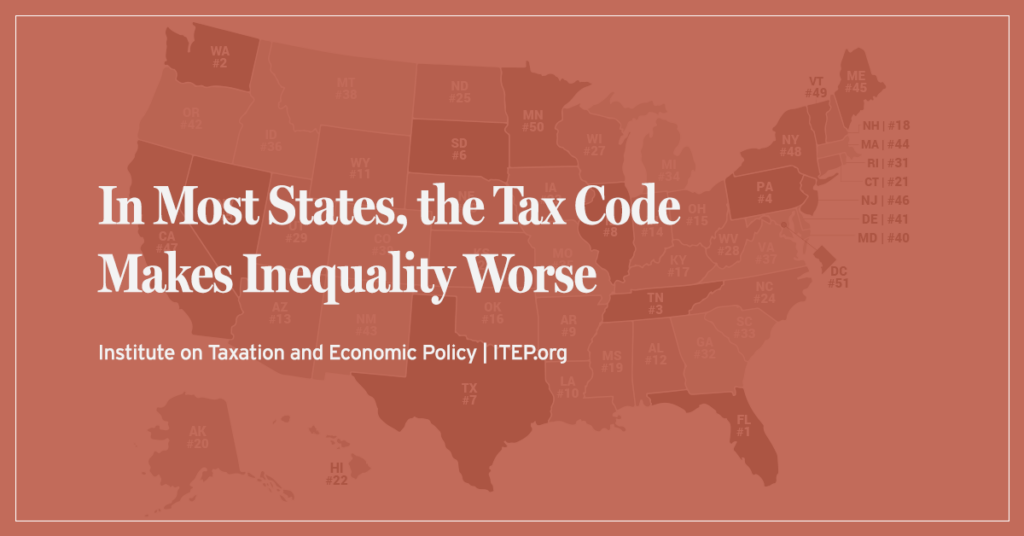

The Case for More Progressive State and Local Tax Systems, in Charts

April 17, 2024 • By Dylan Grundman O'Neill, Eli Byerly-Duke

In a new chart book, Fairness Matters, we further explore our Who Pays? data with new graphics that reinforce the findings in the main report and demonstrate how state-level tax decisions shape economic divides for better and worse.

While many state lawmakers have spent the past few years debating deep and damaging tax cuts that disproportionately help the rich, more forward-thinking lawmakers have improved tax equity by raising new revenue from the well-off and creating or expanding refundable tax credits for low- and moderate-income families.

The ‘Low-Tax’ Lie: States Hyped for Low Taxes Usually Only Low-Tax for the Rich

February 20, 2024 • By Jon Whiten

It’s hard to go a week without seeing a politician or a news article hype up a state as the place that everyone is moving to – or should move to – because of low taxes. However, there’s a big problem with these proclamations: they aren’t true.

The findings of Who Pays? go a long way toward explaining why so many states are failing to raise the amount of revenue needed to provide full and robust support for our public schools.

The vast majority of state and local tax systems are upside-down, with the wealthy paying a far lesser share of their income in taxes than low- and middle-income families. Yet a few states have made strides to buck that trend and have tax codes that are somewhat progressive and therefore do not worsen inequality.

U.S. Average: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

U. S. Average Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 state and local tax law, presented at 2023 income levels. These figures depict taxes paid by residents to their home states. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.7 percent) state and local tax revenue collected […]

Utah: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Utah Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Utah, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.5 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Utah. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Wyoming: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Wyoming Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Wyoming, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.8 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Wyoming. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Wisconsin: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Wisconsin Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Wisconsin, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.4 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Wisconsin. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

West Virginia: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

West Virginia Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in West Virginia, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.3 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in West Virginia. These figures depict West Virginia’s personal income tax at […]

Virginia: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Virginia Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Virginia, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (98.8 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Virginia. These figures depict Virginia’s standard deduction at its 2024 levels of $8,500 […]

Washington: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Washington Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Washington, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.3 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Washington. As seen in Appendix D, the state’s new Working Families Tax Credit […]

Vermont: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Vermont Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Vermont, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.7 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Vermont. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Tennessee: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Tennessee Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Tennessee, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.3 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Tennessee. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Texas: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Texas Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Texas, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.5 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Texas. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

South Dakota: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

South Dakota Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in South Dakota, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.6 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in South Dakota. State and local tax shares of family income Top […]

Rhode Island: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Rhode Island Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Rhode Island, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly 100 percent of state and local tax revenue collected in Rhode Island. State and local tax shares of family income Top […]

South Carolina: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

South Carolina Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in South Carolina, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.8 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in South Carolina. These figures depict South Carolina’s top income tax rate […]

Oregon: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Oregon Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Oregon, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.5 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Oregon. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Pennsylvania: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Pennsylvania Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Pennsylvania, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.6 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Pennsylvania. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Oklahoma: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Oklahoma Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Oklahoma, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.6 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Oklahoma. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

Ohio: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

Ohio Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in Ohio, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.6 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in Ohio. State and local tax shares of family income Top 20% Income Group […]

North Dakota: Who Pays? 7th Edition

January 9, 2024 • By ITEP Staff

North Dakota Download PDF All figures and charts show 2024 tax law in North Dakota, presented at 2023 income levels. Senior taxpayers are excluded for reasons detailed in the methodology. Our analysis includes nearly all (99.9 percent) state and local tax revenue collected in North Dakota. State and local tax shares of family income Top […]

Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States is the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s flagship report. First published in 1996, and updated most recently in 2024, Who Pays? shows the distributional impact by income level of all major state and local taxes in each state, as well as in the District of Columbia. This section highlights related Who Pays? resources, articles and information.