During his first State of the Union address in January 1964, Lyndon Baines Johnson declared a War on Poverty in response to a national poverty rate of more than 19 percent.

The legislative result of this war was an early education program, expanded funding for secondary education, job training and work opportunity programs and the creation of Medicare and Medicaid. In other words, there was a clear recognition that society had a moral obligation to help its most vulnerable. There was also an understanding that reducing poverty in a nation in which nearly one in five were poor required addressing basic human needs such as health care while also providing opportunities to move out of poverty.

By 1973, the federal poverty rate had dropped to 11.1 percent; since then, it has varied between 11.2 to 15.2 percent and, based on the latest data available, is currently 12.7 percent. But the current poverty rate alone doesn’t paint a clear picture of what has happened to Americans’ economic status.

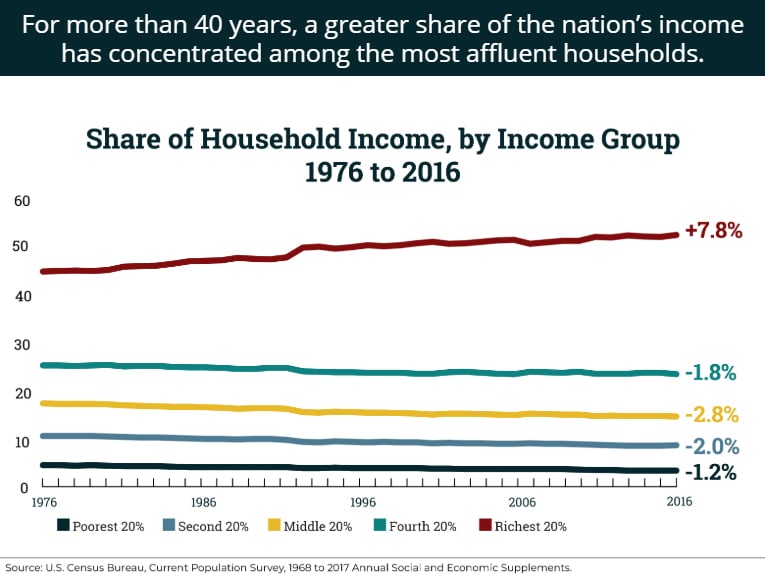

The income divide between rich and poor has grown continually since 1974. The richest 20 percent now capture 8 percent more of the nation’s income than it did then, and the middle-income quintile now collectively has 3.2 percent less of the nation’s income. At the same time, those with the fewest economic resources have fallen deeper into poverty. Between 1996 and 2011, extreme poverty, that is living on less than $2 per person per day, doubled for families with children. For the poorest 10 percent of female-headed households with children, average family income has declined since 1995, while income for other similarly situated families rose. The changes in income distribution and concentration of wealth at the top are the result of policy choices.

While President Johnson didn’t articulate a vision for an acceptable poverty rate, his landmark 1964 address and Great Society goals surely didn’t envision a society in which the rich captured even more of the nation’s wealth while real wages for poor, low- and middle-income workers stagnated or even declined. Even as the nation’s economy has grown over the years, the benefit of that has concentrated at the top. In other words, the pie is growing, but the wealthy are the only group whose slice has grown larger.

It is in this context that the Trump Administration’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) issued a July 2018 report boldly declaring that the nation’s War on Poverty is “largely over and a success,” and calling for more stringent work requirements for families receiving public assistance. The report asserted that the majority of recipients of Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) and federal housing assistance worked fewer than 20 hours per week. But the report relies on data from 2013 when the national unemployment rate was significantly higher. Separate reports using more recent data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Kaiser Family Foundation each found that the majority of recipients of SNAP and non-disabled Medicaid beneficiaries work while receiving benefits.

The CEA report came three months after an April executive order in which the president instructed federal agencies to strengthen existing work requirements and implement new requirements for means-tested assistance programs.

If President Johnson made it clear in his 1964 address to the nation that “lack of jobs and money is not the cause of poverty, but a symptom,” this White House is making it clear that it believes government spending is a root cause of poverty–in spite of evidence that reveals government programs have a measurable impact on reducing poverty. The administration’s public releases touting personal responsibility are not-so-subtle nods to longstanding, erroneous and racist stereotypes about who receives public benefits. Such disparaging tropes about the willingness of poor people to seek employment are a smokescreen designed to both obscure the real reasons policymakers want to cut social service programs and avoid tougher questions about who benefits most in our current economy.

The White House and its allies in Congress may tout work requirements as an essential measure to help the economically disadvantaged “reclaim their independence.” But the true intent of such policies is to cut spending on programs that conservatives hold in ill regard.

Current calls to cut spending on education assistance, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, food assistance and other programs are particularly egregious because they aim to address a budgetary shortfall created in part by the recent deficit-financed tax law, which overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy and corporations. In fact, before the law passed, Speaker Paul Ryan and other GOP leaders admitted that the caucus would seek to shave domestic programs in the wake of the tax cuts to address the deficit.

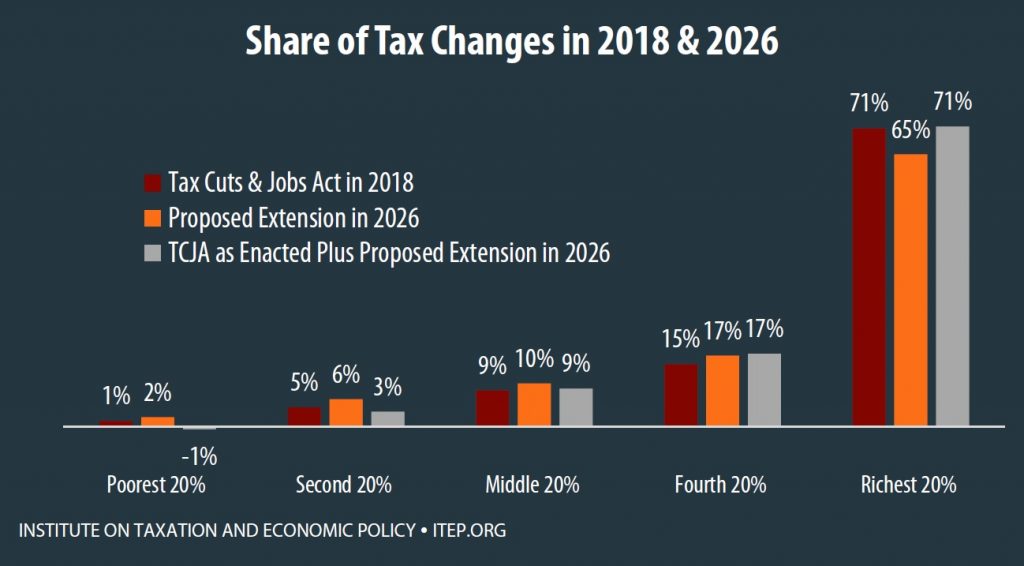

Nearly half of the benefit from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will go to the top 5 percent of households in 2018; 71 percent will go to the top 20 percent. The richest 1 percent of households will receive an annual cut averaging $55,000. The costly tax law’s individual provisions are set to expire after 2025, but the White House and GOP leaders have proposed extending the temporary provisions of the law, expanding the preferential tax treatment of capital gains income, and making permanent the preferential treatment of pass-through income. Each of these proposals would overwhelmingly benefit the wealthiest—and further increase annual deficits.

Too many elected officials have made it clear that they have separate sets of rules for rich people and poor people. In their view, deficits are okay to finance tax cuts mostly for the rich and corporations. But the nation has to carefully consider whether it can pay for programs such as health care, Social Security, education, etc. And, furthermore, poor people must prove they are meeting work requirements in exchange for government assistance. ITEP’s federal policy director, Steve Wamhoff, wrote about this double standard in No Work Requirements for the Richest 1 Percent. Of the $70 billion in tax cuts in the TCJA that go to the richest 1 percent, $39 billion, or 56 percent, are due to corporate tax cuts which ultimately flow to wealthy, stock owning households. This means the richest 1 percent of tax payers will receive a $39 billion tax cut for income for which they did not work. Further, income derived from capital gains is taxed at a special low rate. The nation’s tax policies seek to preserve and grow wealth for the rich at any cost, without regard for how to maintain an adequately funded government.

Additionally, the median white family has almost 10 times as much wealth as the median black family—meaning policies that favor unearned income from wealth over earned income from work further exacerbate the racial wealth gap.

Work requirements are tied to a fundamental misunderstanding of the causes of poverty. Evidence shows that work requirements aren’t effective. In 1996, so-called welfare reform drastically changed the federal cash assistance program and, among other changes, implemented strict work requirements. A comprehensive review of work requirement policies for cash assistance programs found the programs do not decrease poverty or lead to long-term employment. Work requirements are effective at creating a barrier for vulnerable families and limiting their access to assistance. In 1996, 68 out of every 100 families in poverty received Aid to Families of Dependent Children (AFDC), the federal cash assistance program. But 20 years later AFDC’s replacement, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), only served 23 out of every 100 families in poverty.

After President Johnson initially declared an unconditional War on Poverty, he followed up with programs intended to address the root causes of poverty. Within a decade, his actions proved fruitful. Poverty declined by 41 percent from 1964 to 1974. A lot has changed since then, however. Fewer workers are part of collective bargaining units, which are known to boost wages. Corporations have allowed CEO and other executive compensation to skyrocket while wages for ordinary workers have remained stagnant. The federal minimum wage has not risen at the same rate as inflation and has less buying power today than it did in the 1960s. And tax policies over the last two decades have boosted after-tax income more for the rich than any other income group. These policies have proven most damming for those with the fewest resources.

Work requirements for the poor, many of whom are already employed but cannot make ends meet in this economy, will not fix these structural problems. Instead of talking about these longstanding challenges, the White House and congressional leaders are focused on work requirements and policies that lavish the rich and punish the poor.

Jenice Robinson, Communications Director, contributed to this post.