Tennessee lawmakers are giving serious consideration to repealing their state’s “Hall Tax” on investment income (so named for the state senator who sponsored the legislation creating the tax more than eighty years ago). But the Hall Tax is an important revenue source for both state and local governments, and is a rare progressive feature of a tax system that falls disproportionately on the poorest Tennesseans.

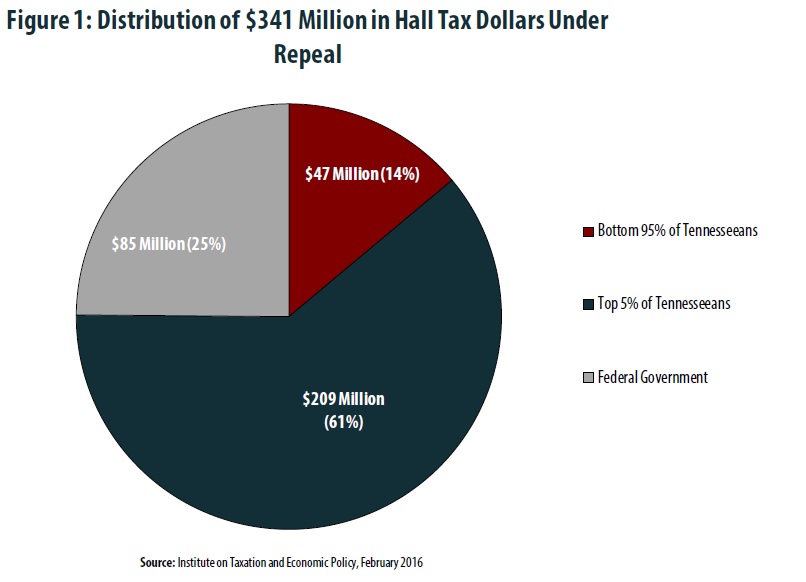

A new analysis performed using the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model shows that the vast majority of Tennesseans would see very little benefit from Hall Tax repeal. Over 60 percent of the tax cuts would flow to the wealthiest 5 percent of Tennessee taxpayers, while another 25 percent would actually end up in the federal government’s coffers. Moreover, if localities respond to Hall Tax repeal by raising property taxes, some Tennesseans could actually expect to face higher tax bills under this proposal.

How the Hall Tax Works

Tennessee is one of nine states that do not levy a broad-based personal income tax on their residents’ earnings, but the state does collect a 6 percent tax on dividends, interest, and some capital gains income. The first $2,500 of investment income ($1,250 in the case of single filers) collected by Tennesseans each year is exempt from the tax, meaning that most Tennesseans pay nothing in Hall Tax each year. In order to ensure that low- and middle-income senior citizens who may be living off their investments are not impacted by the Hall Tax, taxpayers over age 65 who earn less than $68,000 per year in total income (or $37,000 for single filers) are also exempt from paying the tax.

For Fiscal Year 2017, Tennessee officials estimate that the Hall Tax will generate $341 million in revenues. (1) Of that amount, more than a third, or roughly $118.5 million, will go to local governments. (2)

Who Benefits from Hall Tax Repeal?

Because the vast majority of investment income subject to the Hall Tax is collected by high-income taxpayers with large amounts of accumulated wealth, most Tennesseans would see little if any direct benefit from repealing the tax.

Figure 1 shows that the bottom 95 percent of Tennessee residents would receive just $47 million (or 14 percent) of what would amount to a $341 million tax cut overall.

Nearly two-thirds (61 percent, or $209 million) of the tax cuts would go to the wealthiest 5 percent of Tennesseans alone. According to the 2015 edition of ITEP’s Who Pays? study, members of this group already pay a much lower effective state and local tax rate than their less affluent neighbors. (3) High-income Tennesseans face a combined state and local tax rate of between 3.0 and 4.1 percent once sales, excise, property, and income taxes are taken into account. Lower-income taxpayers, by contrast, can find themselves devoting as much as 10.9 percent of their income to paying state and local taxes. This lopsided distribution is enough to earn Tennessee the unfortunate distinction of having the seventh most regressive tax system in the entire country. (4) Repealing the Hall Tax would only exacerbate this regressivity.

Finally, the remaining $85 million of the $341 million proposal to repeal the Hall Tax would not go to Tennesseans at all, but would rather flow into the federal government’s coffers in the form of higher federal income tax payments by Tennessee residents. Since Tennesseans can write off their Hall Tax payments on their federal tax returns, each dollar in Hall Tax paid can generate substantial federal tax savings for those taxpayers who itemize their deductions. (5) Eliminating the Hall Tax would cause Tennesseans to lose any benefit from this federal deduction, and would essentially force them to claim the (generally less lucrative) deduction for state sales taxes instead. The end result of this “federal offset” effect is to negate 25 percent of the tax savings that Tennesseans might have expected to result from Hall Tax repeal.

How Would Different Taxpayers Fare?

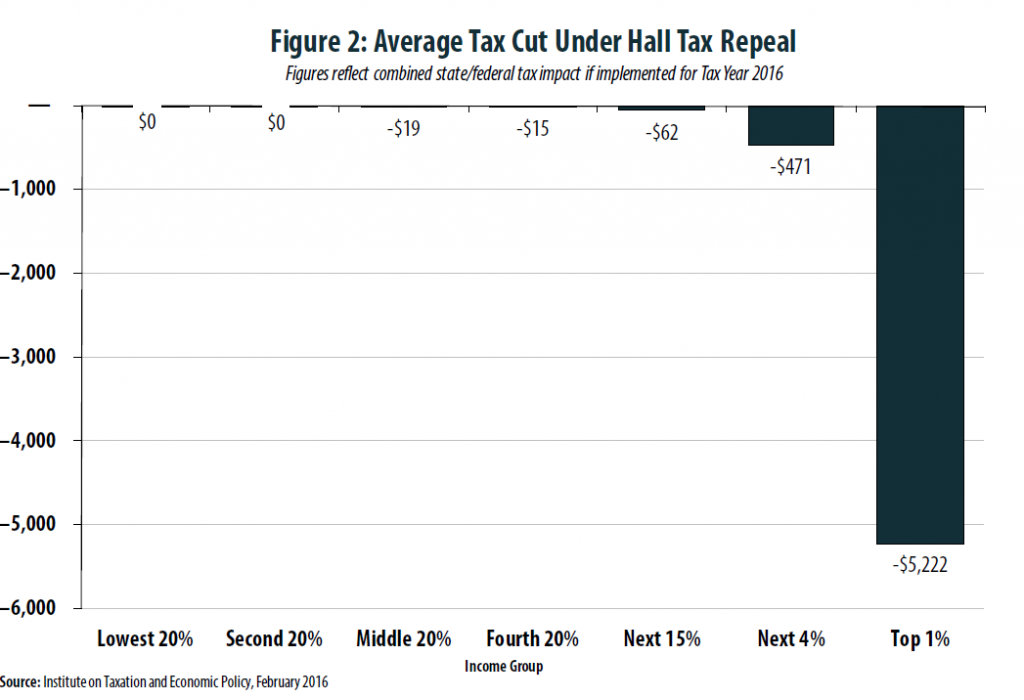

Figure 2 shows that the vast majority of Tennesseans could expect to receive well under $50 per year from repeal of the Hall Tax, and that many Tennesseans would see no tax benefit at all. The wealthiest 1 percent of Tennesseans (earning an average income of $1.2 million), by contrast, could expect to see more than $5,000 in tax cuts per year.

It is important to note, however, that these figures assume local governments would respond to the loss of Hall Tax revenue exclusively by cutting spending on local services like schools, roads, and fire protection. If localities instead opt to raise property taxes in order to compensate for some of the revenue loss, many Tennesseans (particularly those with low levels of interest or dividend income) would actually see their overall state and local tax bills increase as a result of Hall Tax repeal.

Conclusion

Repealing the Hall Tax would significantly reduce the revenues available to fund state and local public services and would tilt Tennessee’s highly regressive tax system even more heavily in favor of the wealthy. Moreover, this proposal produces a relatively low bang-for-the-buck in terms of getting tax cuts into the hands of Tennesseans. One out of every four dollars in foregone revenue would ultimately flow to the federal government because Tennesseans would lose the ability to write-off their Hall Tax payments on their federal tax returns.

(1) State of Tennessee. The Budget: Fiscal Year 2016-2017. Available at: https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/finance/budget/attachments/2017BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

(2) Local governments currently receive 34.75 percent of the Hall Tax payments made by their residents.

(3) Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States. January 2015. Available at: http://www.whopays.org.

(4) Ibid.

(5) For more on this “federal offset” effect, see Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. How State Tax Changes Affect Your Federal Taxes: A Primer on the Federal Offset. August 2011. Available at: https://itep.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/pb7off.pdf.