Impact Of Kamala Harris’ Tax Proposals by Income Group

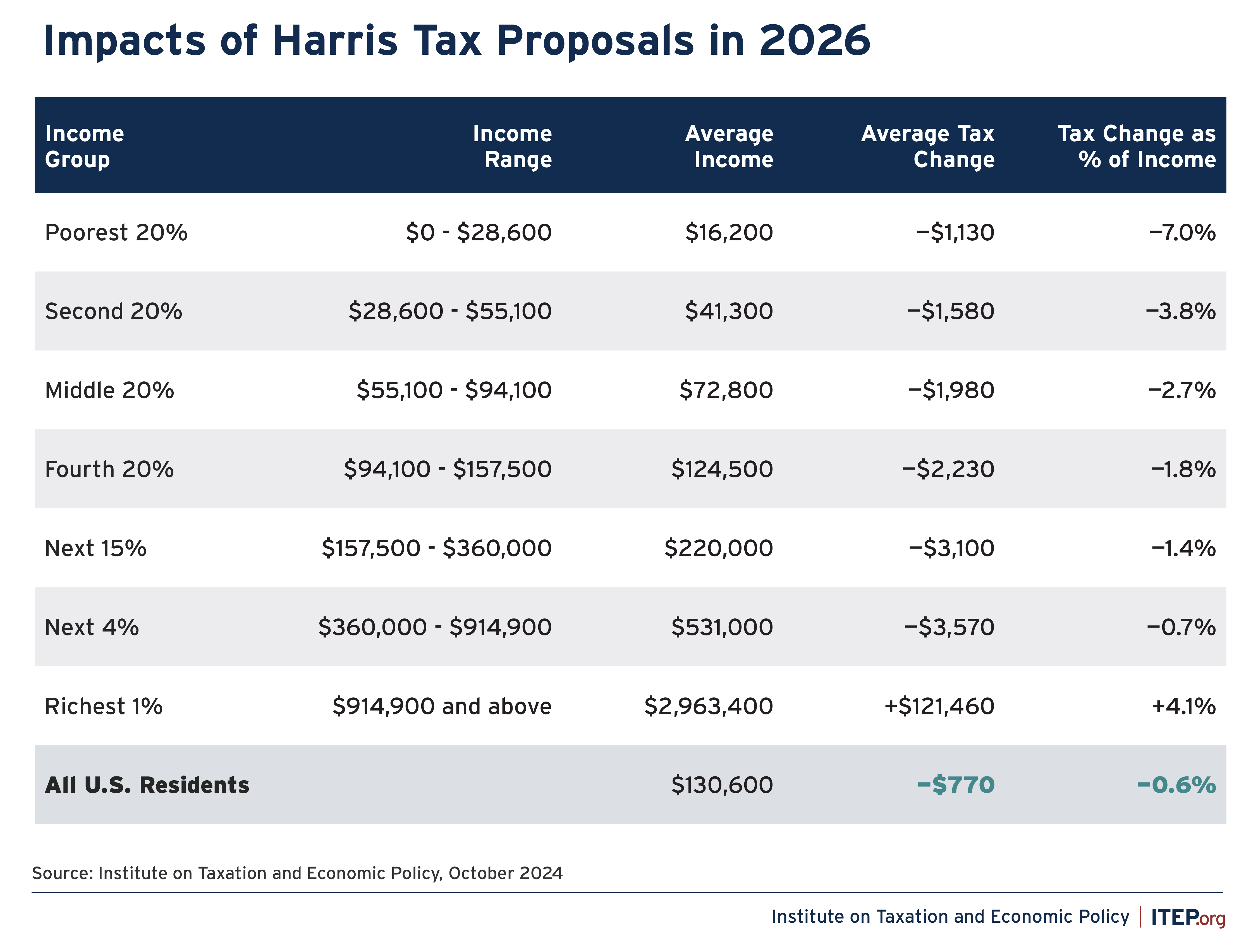

Taken together, the tax changes proposed by Vice President Kamala Harris would raise taxes on the richest 1 percent of Americans while cutting taxes on all other income groups.

If these proposals were in effect in 2026, the richest 1 percent of Americans would receive an average tax increase equal to 4.1 percent of their income. Other income groups would receive tax cuts, including an average tax cut equal to 2.7 percent of income for the middle fifth of Americans and an average tax cut equal to 7 percent of income for the poorest fifth of Americans.

FIGURE 1

This analysis includes tax proposals Harris has explicitly announced and others that are major pieces of President Biden’s tax agenda, which Harris has said she would pursue and which are consistent with her campaign pledges:

- Extending the temporary provisions in the 2017 tax law fully for those with incomes of less than $400,000 but with strict limits on benefits for those with incomes above $400,000

- Helping workers and families with proposals related to raising children and obtaining health coverage, assisting service workers, and making housing more affordable

- Reforming the taxes that fund Medicare, which would raise taxes on those with incomes of more than $400,000

- Scaling back existing tax breaks on capital gains and dividends for those with incomes of more than $1 million (and in some cases far more)

- Reforming the corporate tax code to scale back recently enacted breaks and long-standing loopholes that have been shown to increase income inequality and racial inequality[1]

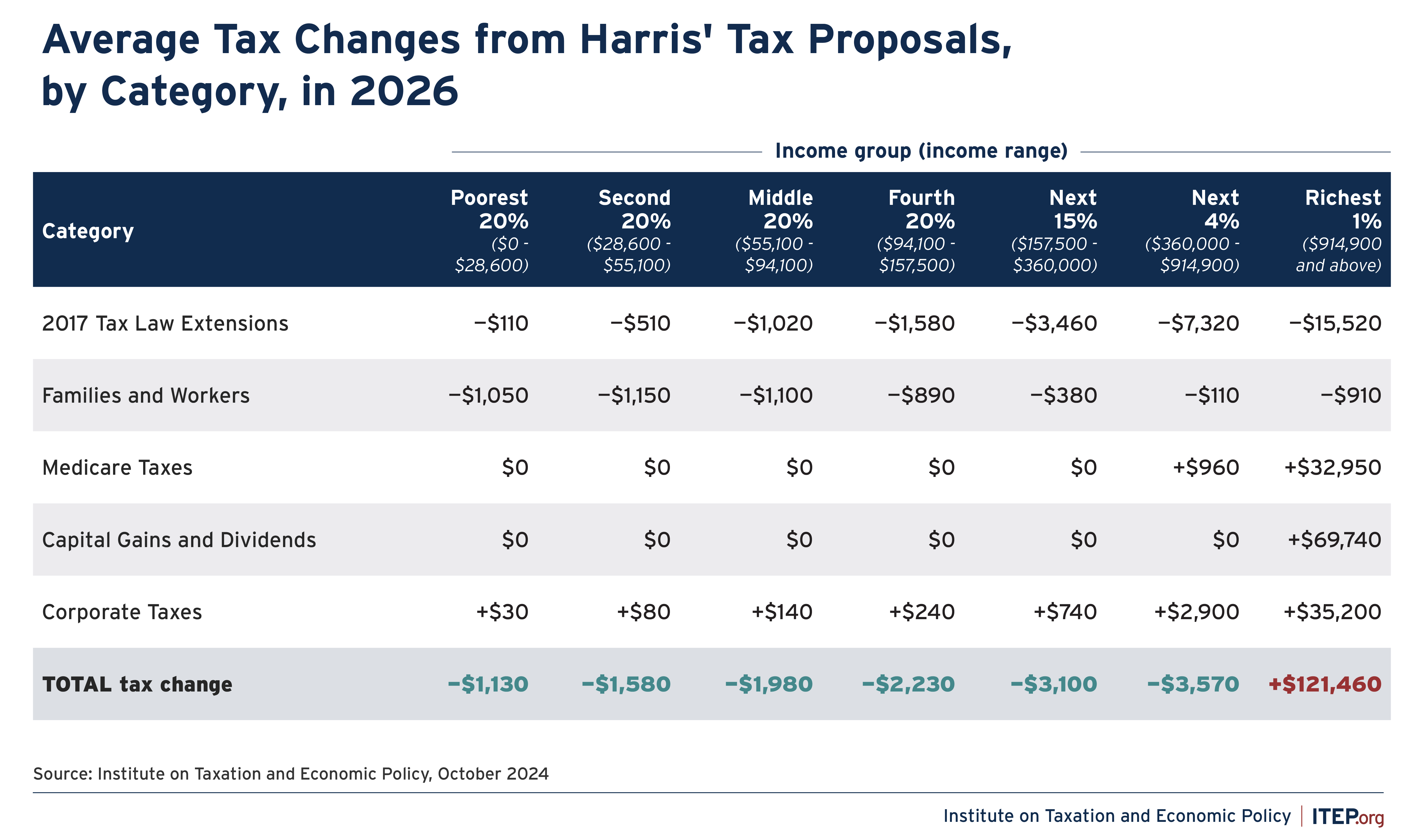

As illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, the different parts of Harris’ tax plan affect income groups quite differently.

For example, Harris’ proposal to extend the temporary 2017 tax provisions – aside from those that mainly benefit taxpayers making more than $400,000 – would cut taxes for all income groups but would provide the smallest tax cut, as a share of income, for the richest 1 percent.

Her proposals for workers and families – including a large expansion of the Child Tax Credit – would be very targeted to those who most need help and would, for example, provide the poorest fifth of Americans with tax cuts equal to 6.5 percent of their income.

Other proposals – reforming Medicare taxes, scaling back tax breaks for capital gains and dividends, and reforming corporate taxes – are all designed to raise taxes on very well-off households.

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 3

This analysis includes tax changes proposed by Harris with explicit details as well as the tax proposals offered by President Biden for which she has expressed support since becoming a candidate for President. For any of her

proposals that lack detail, this analysis interprets them in the most straightforward manner possible. The analysis looks first to how Vice President Harris and her campaign have described the proposals. In addition, to the extent the proposals align with proposals in Congress, the details of those proposals are used to inform the analysis.

Different interpretations of the proposals are possible. The appendix details how the different proposals are distributed by income in our analysis. Within the range of plausible interpretations, the overall conclusion that the Harris tax plan would raise taxes on the richest Americans and cut taxes on the rest overall is unaffected.

FIGURE 4

Overview of Vice President Harris’ Tax Proposals

The appendix at the end of this report includes estimates that are broken down into each category described here.

Partly extend the temporary 2017 tax provisions

- Extend the changes in income tax brackets and rates while restoring the top rate of 39.6 percent for high-income taxpayers as spelled out in President Biden’s budget plans.[2] (The top rate of 39.6 percent would apply to single filers with taxable income of more than $400,000 and married joint filers with taxable income of more than $450,000, adjusted for inflation.)

- Extend the increase in the standard deduction and Child Tax Credit and the provision that offsets most of the costs by repealing personal exemptions.

- Extend the more generous exemption from the Alternative Minimum Tax but phase the benefit out rapidly for those with incomes above $400,000.

- Extend the elimination of some itemized deductions. Also extend the elimination of the overall limit on itemized deductions (often called Pease) but only for those with adjusted gross income below $400,000. This analysis assumes that Harris would not extend the cap on deductions for state and local taxes (SALT).

- Extend the special 20 percent deduction for pass-through business income, but rapidly phase out the deduction for those with taxable income beyond $400,000.

- Allow the provision cutting the estate tax to expire completely.

Proposals for families and workers

- Expand the Child Tax Credit. This includes reviving the expansion that was in effect in 2021, which increased the credit from $2,000 to $3,000 for children ages 6 through 17 and to $3,600 for children ages 0 through 5. This also includes Harris’ proposal to increase the credit to $6,000 for babies in their first year.

- Make permanent a recent expansion of tax credits subsidizing health care insurance premiums under the Affordable Care Act.

- Exempt tips for service and hospitality workers making up to $75,000 from income tax.

- Expand access to affordable housing by creating a tax credit for first time homebuyers, expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), and creating a Neighborhood Homes Tax Credit that would incentivize building and rehabilitating owner-occupied homes.

Reforms to the taxes that fund Medicare

- Close loopholes in the additional Medicare tax on wages and the Net Investment Income Tax, which were both intended to ensure that well-off people pay a 3.8 percent tax on most types of income to help finance Medicare. This proposal would close loopholes that currently allow certain business profits to escape both taxes.

- Raise the top marginal rate on both taxes from 3.8 percent to 5 percent for income exceeding $400,000.

Reforms to the taxation of capital gains and dividends

- Reduce, but not eliminate, the special break that taxes certain investment income at lower rates than income from work. Harris’ proposal would raise the top personal income tax rate on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends from 20 percent to 28 percent for taxable income in excess of $1 million.

- Tax unrealized gains in excess of $5 million (in excess of $10 million for a married couple) on assets passed on to heirs.

- Impose a new minimum tax of 25 percent on extremely wealthy taxpayers’ annual income including unrealized capital gains. This is the Billionaires’ Minimum Income Tax, proposed by President Biden, which would be phased in for taxpayers with a net worth between $100 million and $200 million.

Corporate tax reforms

- Raise the statutory corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent.

- Raise the rate of the corporate minimum tax (enacted as part of the Inflation Reduction Act) from 15 percent to 21 percent.

- Strengthen the existing limit on deductions that corporations take for compensation in excess of $1 million paid to any executive or other employee.

- Enact reforms that would ensure offshore profits of U.S. corporations are taxed at a rate of at least 21 percent, block corporate inversions, and enact an undertaxed profits rule for profits of foreign corporations operating in the U.S.

- Increase the excise tax rate on stock buybacks (enacted as part of the Inflation Reduction Act) from 1 percent to 4 percent.

Appendix: Methodology

ITEP uses the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model to analyze most proposals to modify the personal income tax or social insurance taxes.

The model combines data from the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, and numerous other sources to create a valid representation of the U.S. population, including federal filers and nonfilers.[3]

Its structure mirrors models at the federal level maintained by the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, the U.S. Treasury Department, and the Congressional Budget Office, and at the state level by the Minnesota Department of Revenue and other state agencies. Microsimulation modeling is widely regarded as the best approach to tax policy analysis because of its ability to account for overlapping and interacting tax provisions and to produce results that are representative of the full population.

In some instances, this analysis also incorporates other data sources. For example, the housing related provisions were analyzed using data from the American Housing Survey in conjunction with the ITEP Microsimulation Model. In addition, for the Low-Income Housing Credit expansion, data on that program from the Department of Housing and Urban Development was used.

As Congress’ official revenue estimators, the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) assume that changes to the income tax rates applying to long-term capital gains cause well-off people to change their behavior in certain ways to avoid any rate increase or exploit any rate cut. While recent research suggests that JCT is currently underestimating how much revenue can be raised by increasing income tax rates on capital gains, this analysis nonetheless adopts an approach that we believe is similar to that of JCT in order to have estimates consistent with those used by lawmakers.[4] Like JCT and other analysts, we do not include these behavioral impacts in our estimates of how particular income groups are affected but we do incorporate them into our estimates of revenue impact when they are significant. Among Harris’s plans, only her proposal to raise the top income tax rate on capital gains might have a behavioral impact significant enough to include in this analysis.

For Harris’ proposals to change corporate taxes, ITEP generally begins with revenue estimates from the Department of the Treasury for the most significant proposals in President Biden’s budget submissions to Congress, which Harris has said she generally supports.[5]

While corporate taxes are paid directly by corporations, they are indirectly paid by individuals, most of whom are relatively well-off holders of corporate stocks and bonds. To estimate how the corporate tax changes would indirectly affect individuals across different income groups, we adopt the approach used by the Joint Committee on Taxation and assign the full impact to owners of capital as our analysis examines the immediate impact of such a change in the first year it would be in effect.[6] This includes foreign owners of stocks in U.S. corporations.

Today it is unclear what fraction of U.S. stocks are assumed to be foreign owned under JCT’s analyses, but others find it is now much higher than previously believed. Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke at the Tax Policy Center estimated in 2019 that foreign investors owned 40 percent of the shares in American corporations.[7] (This figure has recently been updated to 42 percent, but ITEP uses the 40 percent estimate for simplicity and because the difference between these figures is small.)[8]

Appendix Data

Endnotes

[1] Steve Wamhoff and Emma Sifre, “Corporate Tax Breaks Contribute to Income and Racial Inequality and Shift Resources to Foreign Investors,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 16, 2024.

[2] Department of the Treasury, “General Explanation of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2025 Revenue Proposals,” March 11, 2024, page 78.

[3] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “ITEP Tax Microsimulation Model Overview.”

[4] Congress’s official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and some other analysts assume that wealthy people respond to higher income tax rates on capital gains by selling fewer assets, and therefore “realizing” fewer capital gains, which in turn can dramatically reduce the revenue increase that would otherwise result from the higher tax on capital gains. The Congressional Research Service has explained that the assumptions used by JCT may be overly pessimistic about how dramatically wealthy people would reduce their realizations of capital gains (and thus overly pessimistic about how much revenue can be raised from capital gains). Congressional Research Service, “Capital Gains Tax Options: Behavioral Responses and Revenues,” Updated January 19, 2021. Several prominent economists, including a former Treasury official and former Treasury Secretary, have argued that JCT’s assumptions are too pessimistic and are based on studies that are out of date. Natasha Sarin, Lawrence H. Summers, Owen M. Zidar, Eric Zwick, “Rethinking How We Score Capital Gains Tax Reform,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 28362, January 2021. This analysis nonetheless takes a conservative approach in that it uses the same assumptions as JCT when analyzing the long-term impact of tax changes on capital gains realizations. This analysis also incorporates an approach used by the Tax Policy Center that assumes the proposal to tax some unrealized gains at death, which Harris also proposes, would lessen the behavioral response and increase the overall revenue impact. See Mermin et al., “An Analysis of Former Vice President Biden’s Tax Proposals,” Tax Policy Center, March 5, 2020, footnote 1.

[5] Department of the Treasury, “General Explanation of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2025 Revenue Proposals,” March 11, 2024.

[6] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Modeling the Distribution of Taxes on Business Income,” October 16, 2013, JCX-14-13.

[7] Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” Tax Policy Center, October 27, 2020.

[8] Steven M. Rosenthal and Livia Mucciolo, “Who’s Left to Tax? Grappling With a Dwindling Shareholder Tax Base,” Tax Notes, April 1, 2024.