On the surface, census poverty and income data released Tuesday reveal the nation’s economic conditions are improving for working families. The federal poverty rate declined for the second consecutive year and is now on par with the pre-recession rate. For the first time, median household income surpassed the peak it reached in 1999 and is at the highest level ever recorded at $59,039.

But a deeper look at the numbers reveals the worrying, 40-year trend of stagnant income and widening inequality persists. The increase in median household income is nothing to sneeze at, but in truth it isn’t substantially higher than its 1999 level of $58,665 when adjusted for inflation. Ordinary families more or less have the same buying power today as they did two decades ago.

Further, the 2016 data reveal that average incomes among the bottom 20 percent of earners were nearly $600 less in 2016 than a decade ago ($12,943 today v. $13,514 in 2006). The poor literally have grown poorer over the last 10 years [See Income and Poverty in the United States: 2016, page 31]. Meanwhile, average household income for the top income quintile grew to $213,941 in 2016 from $200,192 a decade prior—a nearly 7 percentage-point jump. Not only did income for the top 20 percent grow more substantially than for other income quintiles, the top group also captured a slightly larger share of income in 2016 than it did the previous year. In other words, more of the nation’s income concentrated among top-earning households.

Robert Greenstein, executive director of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, wrote a summary of the census data that puts the mixed bag in perspective. He noted, “The challenge for policymakers now is to build on the last few years’ progress and not worsen poverty, inequality, and health coverage.”

This means that as our elected officials debate legislation that affects economic conditions, they should keep the census data in mind.

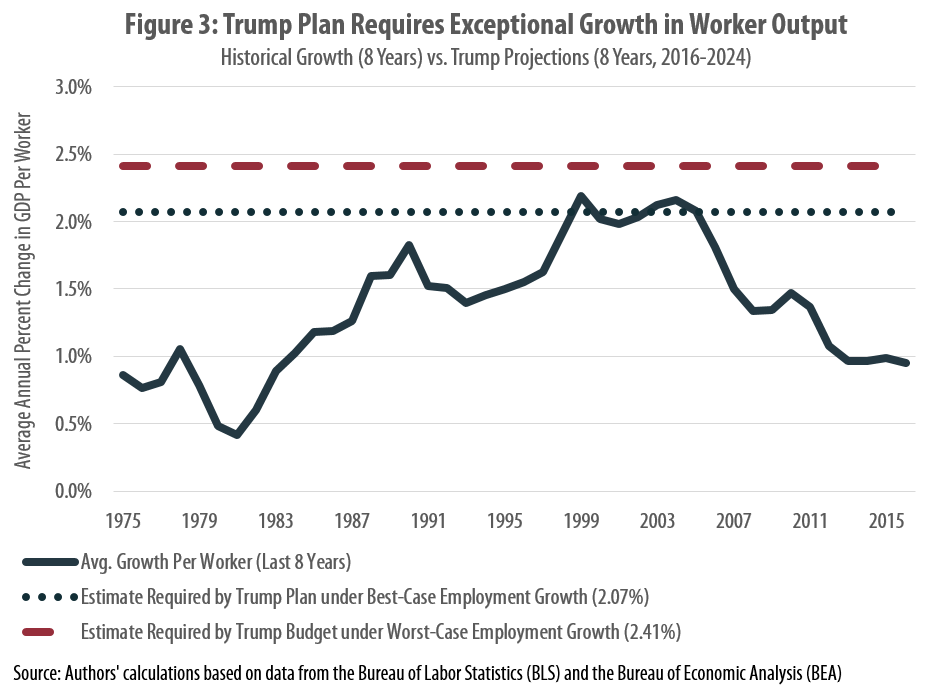

The data are particularly relevant to the current debate over the federal tax code. GOP leaders, the White House and anti-tax advocates have launched a well-coordinated public relations campaign to convince the public that tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy will spur the economy and benefit the middle class. Such supply-side economic theories, which claim that tax cuts will unleash economic growth and thus make up for revenue loss due to tax cuts, are unproven.

And with marginal economic progress for working families, the nation simply cannot talk about tax cuts in a vacuum. Less tax revenue means less money for programs and services that are vital to  families’ financial health. Handing out tax cuts for all (but mostly for the rich) today will mean less revenue to fund those services tomorrow—unless trickle-down economic theories magically work this time.

families’ financial health. Handing out tax cuts for all (but mostly for the rich) today will mean less revenue to fund those services tomorrow—unless trickle-down economic theories magically work this time.

GOP leadership has said it will release a consensus tax plan later this month. The plan will have to be a radical departure from the proposals outlined by President Trump in April (not to mention previous tax and budget plans released by GOP leadership) if it is to be anything other than a giveaway to the wealthy and corporations. Multiple ITEP analyses have made clear that the White House’s tax proposals so far would use the guise of “tax reform” to redistribute wealth to those who are already rich on an unprecedented scale.

ITEP’s first analysis of the White House’s tax proposal revealed that the top 1 percent of taxpayers would receive 61.4 percent of the proposed tax cut, worth an average $145,400. The bottom 20 percent of earners, by contrast, would receive an average of just $130. A second ITEP analysis broke down the numbers further to households earning at least $1 million annually and found that millionaires would receive nearly half of the president’s proposed cuts, increasing their after-tax income by more than $217,000.

Put another way, Trump would use the tax code to deliver an annual income boost to millionaires that is worth nearly four times the nation’s median household income.

But that’s not all. A new analysis released Wednesday by ITEP examines effective total (combined federal, state and local) tax rates paid by each income group under current law and compares them to taxes people would pay under the president’s proposals.

The Trump tax plan would shred the U.S. tax code’s moderate progressivity by reducing taxes on the rich so drastically that their overall rate would be on par with middle-income families and fall below rates paid by upper middle-class families. This sharp cut also would redistribute the responsibility of paying taxes in a major way, effectively increasing the share of the nation’s total tax bill paid by every group except the top 1 percent of earners.

A recent report by the Institute for Policy Studies dispels the myth that cutting the corporate tax rate would spur jobs creation. Using ITEP data on corporate tax rates, the study examines corporations that were consistently profitable over eight years and paid an average effective rate of less than 20 percent (GOP leaders are seeking a tax rate in this range). It found that firms with lower effective tax rates paid their already wealthy executives more but did not create jobs. In fact, some downsized jobs.

The reality is that the GOP’s approach to tax policy would hardly be a boon for the middle class as the White House, its emissaries and Republican leaders are claiming. Instead, it would give an even bigger share of the pie to those who already had the biggest piece in the first place.

Polls show that the vast majority of Americans do not want tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. Yet the White House and GOP leaders persist, essentially covering a bitter tax-cut pill with peanut butter and force feeding it to the public.

With little growth in wages for many households, it’s morally reprehensible for the nation’s lawmakers to consider any tax proposal that would redistribute the nation’s wealth upward by boosting after-tax income for the very richest and shifting the responsibility for the nation’s tax bill to hardworking people who have barely recovered from the 2007-2009 economic recession. Census data tell an important story about long-term poverty and income trends and how families are financially faring. If policymakers’ true goal is to boost the lot of working families, they cannot ignore these data as they consider tax changes.