Key findings

• The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act would reform the taxes that Americans pay to finance these two important programs so that the richest 2 percent of Americans pay these taxes on most of their income the way that middle-class taxpayers already do.

• Most working Americans receive all or nearly all their income in the form of earnings from work and pay taxes on all these earnings to finance Medicare and Social Security. But the same is not true for high-income people.

• First, the Social Security tax only applies to earnings up to a capped amount (which is projected to be $170,400 next year) and high-income individuals can have earnings far exceeding this threshold. Earnings above this threshold are subject only to taxes meant to finance Medicare, which are smaller than the Social Security tax.

• Second, high-income people are likely to receive much more of their income from investments, which is not subject to Social Security taxes at all and is only subject to a much smaller tax meant to finance Medicare.

• The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act would address this and would increase taxes for just 2 percent of Americans to improve the finances of these programs.

• Virtually no one outside of the richest 5 percent of taxpayers would pay more under the proposal and 93 percent of the total tax increase would be paid by the richest 1 percent alone in 2024.[1]

How Taxes Pay for Social Security and Medicare

Social Security is currently financed by a 12.4 percent tax on earnings, up to the cap (which is projected to be $170,400 next year). The tax is technically split in half, with 6.2 percent paid by the employee and 6.2 percent paid by the employer. But analysts generally believe the employer share of the tax is passed on to the employee in the form of reduced compensation, so ultimately employees are paying the entire tax. For self-employment earnings, the entire 12.4 percent tax applies.[2]

Medicare is financed mostly by a 2.9 percent tax on earnings, although an “additional Medicare” tax of 0.9 percent effectively provides a second bracket, with a rate of 3.8 percent, for married couples making more than $250,000 and others making more than $200,000.

The regular Medicare tax of 2.9 percent is technically split in half when paid on employment earnings, so that 1.45 percent is paid by the employee and the other 1.45 percent is paid by the employer. Again, analysts believe the employer share of the tax is ultimately paid by the employee in the form of reduced compensation. (The additional Medicare tax of 0.9 percent on earnings is all paid directly by the employee with no employer-employee split.)

While middle-income Americans do not pay any Medicare tax on investment income, high-income people pay a Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) of 3.8 percent on investment income that pushes their Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) beyond $250,000 for married couples and beyond $200,000 for others. While NIIT revenue technically is not directed to Medicare under current law, the general idea is that well-off people will pay a tax with a top rate of 3.8 percent on their income to help pay for Medicare, whether that income is earned income or investment income.

Taken on their own, the taxes that finance Social Security are regressive because they only apply to earnings (not investment income) and because these earnings are capped at a level far below what the best-compensated Americans make every year.[3]

However, the Social Security program as a whole is progressive because the benefits replace a larger share of earnings for low-income people than for high-income people. Under the formula used to calculate benefits, there is a maximum limit on benefits that can be paid to high earners just as there is a maximum limit on Social Security taxes paid by high earners.[4]

There are strong reasons to make the financing of these programs more progressive. For one thing, as the share of earnings flowing to the highly compensated grows, the share of total earnings in the U.S. that are subject to Social Security taxes has fallen. According to the Congressional Budget Office, 90 percent of earnings in the U.S. were subject to Social Security taxes in 1983, but now the share has fallen to 83 percent.[5]

How the Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act Would Change These Taxes

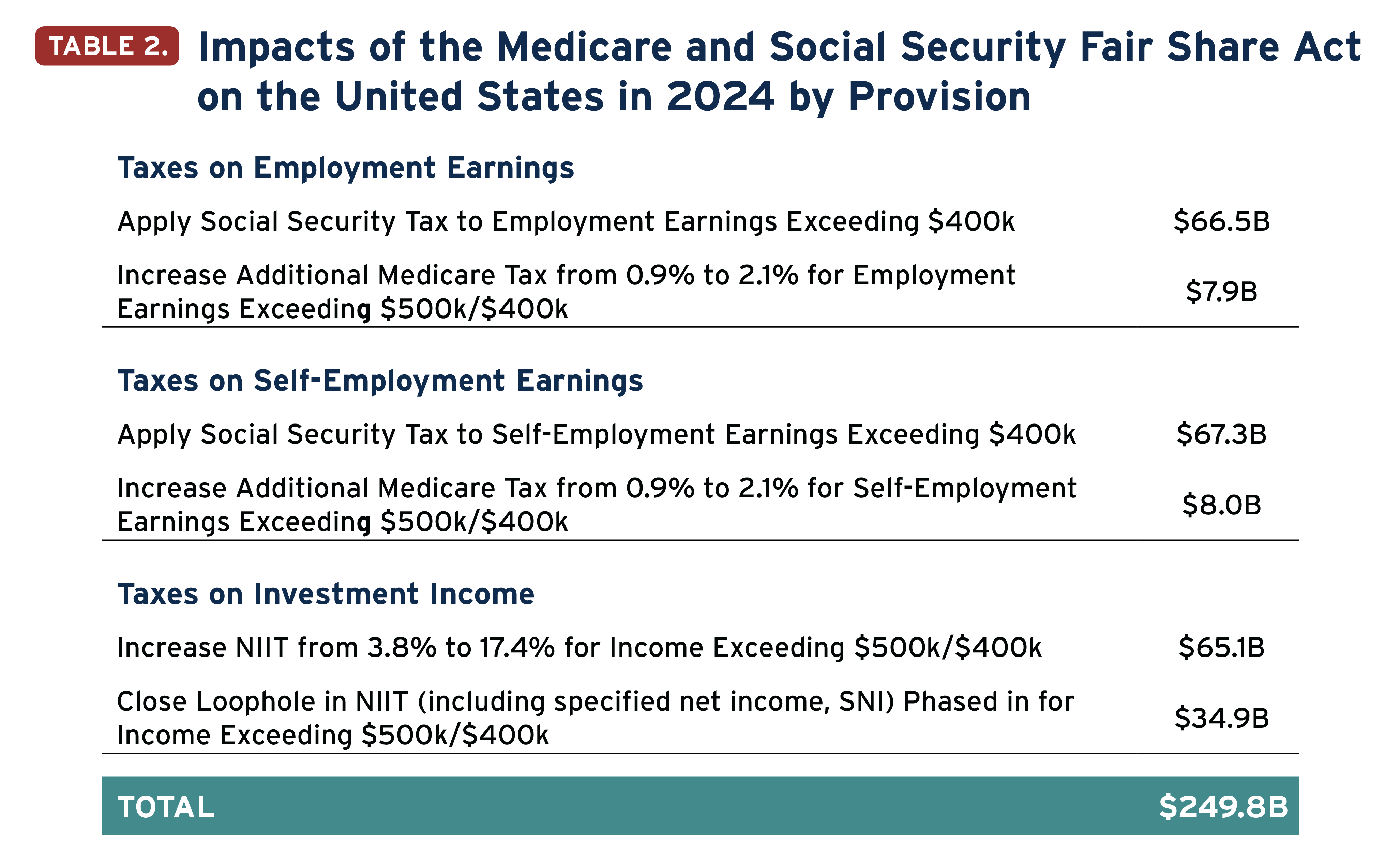

The Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act introduced by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse would increase these taxes in several ways to ensure that well-off people pay a tax of 17.4 percent on their income to fund Medicare and Social Security, whether that income is earned or generated from investments. Table 2 lists the estimated revenue impact of each change in 2024.

First, the 12.4 percent tax that funds Social Security would apply to most employment earnings of the rich – not on all earnings above the current cap but on earnings exceeding $400,000.[6],[7]

Second, the “additional Medicare tax,” which effectively creates a top rate of 3.8 percent on earnings to fund Medicare, would have a new bracket to effectively create a top rate of 5 percent.

Third, the 12.4 percent Social Security tax would also apply to self-employment income.

Fourth, the increase in the “additional Medicare tax” on earnings would also apply to self-employment earnings.

Fifth, the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), which currently has a rate of 3.8 percent and is meant to ensure that well-off Americans pay taxes on their investment income to finance Medicare at the same rate as is paid on earned income, would be increased to 17.4 percent for married couples with AGI exceeding $500,000 and others with AGI exceeding $400,000.[8] This would ensure that the richest Americans are paying tax on their investment income to finance both programs at the same rate as they pay on their earned income. (For earned income, the 12.4 percent Social Security tax and the 5 percent Medicare tax would come to 17.4 percent.)

The effects of these changes on the total social insurance tax rates paid by the well-off are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 below.

A sixth and final change in the bill would close a loophole that allows certain income to escape the regular Medicare tax on earnings, the additional Medicare tax on earnings, and the NIIT. It would do this by requiring taxpayers to calculate the tax increase they would pay if they calculated the NIIT with an expanded definition of investment income (including income that usually escapes these taxes) and then phases in the resulting tax increase for married couples with AGI exceeding $500,000 and other taxpayers with AGI exceeding $400,000. President Biden has included this proposal in his budget plans.[9]

Endnotes

[1] There would technically be some rare exceptions to this. For example, there were years when Donald Trump is likely to have reported earnings or investment income high enough to be affected by this proposal, even though the business losses he reported had the effect of making him "poor” for purposes of the personal income tax. Russ Buettner, Susanne Craig and Mike McIntire, “Long-Concealed Records Show Trump's Chronic Losses and Years of Tax Avoidance,” New York Times, September 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/27/us/donald-trump-taxes.html

[2] Self-employment taxes apply to 92.35 percent of self-employment income rather than the whole amount. The idea is that employers can deduct the payroll taxes they pay on behalf of the employee and this is meant to provide similar treatment to the self-employed.

[3] Medicare taxes do not have these problems, at least not to the same extent. The earnings cap applied to the Medicare tax as well until 1994 when Congress made all earnings subject to the Medicare tax. The additional Medicare tax of 0.9 percent, which was introduced as part of the Affordable Care Act, made the Medicare tax on earnings more progressive by effectively giving it a second bracket of 3.8 percent for high-earners. And the NIIT, which was also introduced as part of the Affordable Care Act, ensured that investment income, at least for well-off Americans, is taxed at the same rate of 3.8 percent.

[4] Congressional Budget Office, "Is Social Security Progressive?," December 15, 2006. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/109th-congress-2005-2006/reports/12-15-progressivity-ss.pdf

[5] According to CBO, the share fluctuated over time but was 92 percent at the start of the program in 1937. Congressional Budget Office, “Options for Reducing the Deficit, 2023 to 2032, Volume I: Larger Reductions.” https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/58630

[6] This would leave a “donut hole,” meaning the wages between the existing cap of $170,400 next year and the $400,000 threshold would remain untouched by this tax. However, the donut hole would eventually close because the existing cap of $170,400 is indexed for wage inflation while the $400,000 would not be indexed, meaning the lower cap would keep rising until eventually surpassing $400,000.

[7] It is not clear how exactly employers would respond to this change but the employer-side payroll tax must either be borne by employers (which would mean employers report smaller profits and thus pay less taxes) or passed on and borne by employees in the form of reduced compensation (which would mean that the taxes employees pay under current law would be reduced somewhat). Because this proposal would make a permanent change in the tax system, this analysis takes the long-term view and assumes that the employer side of the payroll tax would be ultimately borne by employees in the form of reduced compensation. This results in a small decrease in the taxes that apply under current law, like the personal income tax and the “additional Medicare tax” on earnings. But the revenue impact of this reduction in reported earnings is relatively small. This analysis finds that in 2024, the resulting reduction of reported earnings of the rich would cause revenue to fall by $16 billion but the revenue increase from applying the Social Security tax to earnings exceeding $400,000 would generate about $83 billion in new revenue, for a net revenue impact of $66.5 billion in 2024 as shown in Table 2.

[8] Much of the investment income that would be subject to the increased NIIT is capital gains, the profits that investors receive from selling assets for more than they paid to purchase them. Congress’s official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and some other analysts assume that wealthy people respond to such changes by selling fewer assets, and therefore “realizing” fewer capital gains, which in turn can dramatically reduce the revenue increase that would otherwise result from the higher tax on capital gains. The Congressional Research Service has explained that the assumptions used by JCT may be overly pessimistic about how dramatically wealthy people would reduce their realizations of capital gains (and thus overly pessimistic about how much revenue can be raised from capital gains). Congressional Research Service, “Capital Gains Tax Options: Behavioral Responses and Revenues,” Updated January 19, 2021. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41364. Several prominent economists, including a former Treasury official and former Treasury Secretary, have argued that JCT’s assumptions are too pessimistic and are based on studies that are out of date. Natasha Sarin, Lawrence H. Summers, Owen M. Zidar, Eric Zwick, “Rethinking How We Score Capital Gains Tax Reform,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 28362, January 2021. http://www.nber.org/papers/w28362

This analysis nonetheless takes a conservative approach in that it uses the same assumptions as JCT when analyzing the long-term impact of tax changes on capital gains realizations. Like JCT and other analysts, we do not include these behavioral effects in our distributional tables, which is why Table 1 shows a total tax change of $316.9 billion for 2024, larger than the total in our revenue estimates in Table 2, which comes to $249.8 billion. The difference, a reduction in revenue of $67 billion, is the estimated impact of the behavioral responses to the higher NIIT applying to capital gains. In other words, the revenue reduction of $67 billion is the result of wealthy people holding onto their assets longer to avoid the tax increase, based on the assumptions used by JCT.

[9] Joe Hughes, “Key Reform in Build Back Better Act Would Close Loophole Used by the Rich To Avoid Funding Healthcare,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, November 18, 2021. https://itep.org/key-reform-in-build-back-better-act-would-close-loophole-used-by-the-rich-to-avoid-funding-healthcare/