This year millions of American families are finding that their refunds are much smaller than last year—or that they even owe taxes back to the government. And not because of filing mistakes or changes in income but because of the expiration of the expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) that were in effect in 2021. Many lawmakers attempted to extend these credits at least for 2022 to no avail. The lapse of the expanded credits affects a majority of the middle class, but lower-income households are particularly likely to feel the sting.

The EITC and the CTC, created in 1975 and 1997, together reduce child poverty, boost incomes of families raising kids, and inject income into communities that need it, all good things. What the pandemic-era policies showed us is that more of a good thing is sometimes better. The expanded credits slashed poverty and helped young workers and families get their feet on the ground in an uncertain economy. They were well-designed policies to assist the middle class and the most vulnerable in our country.

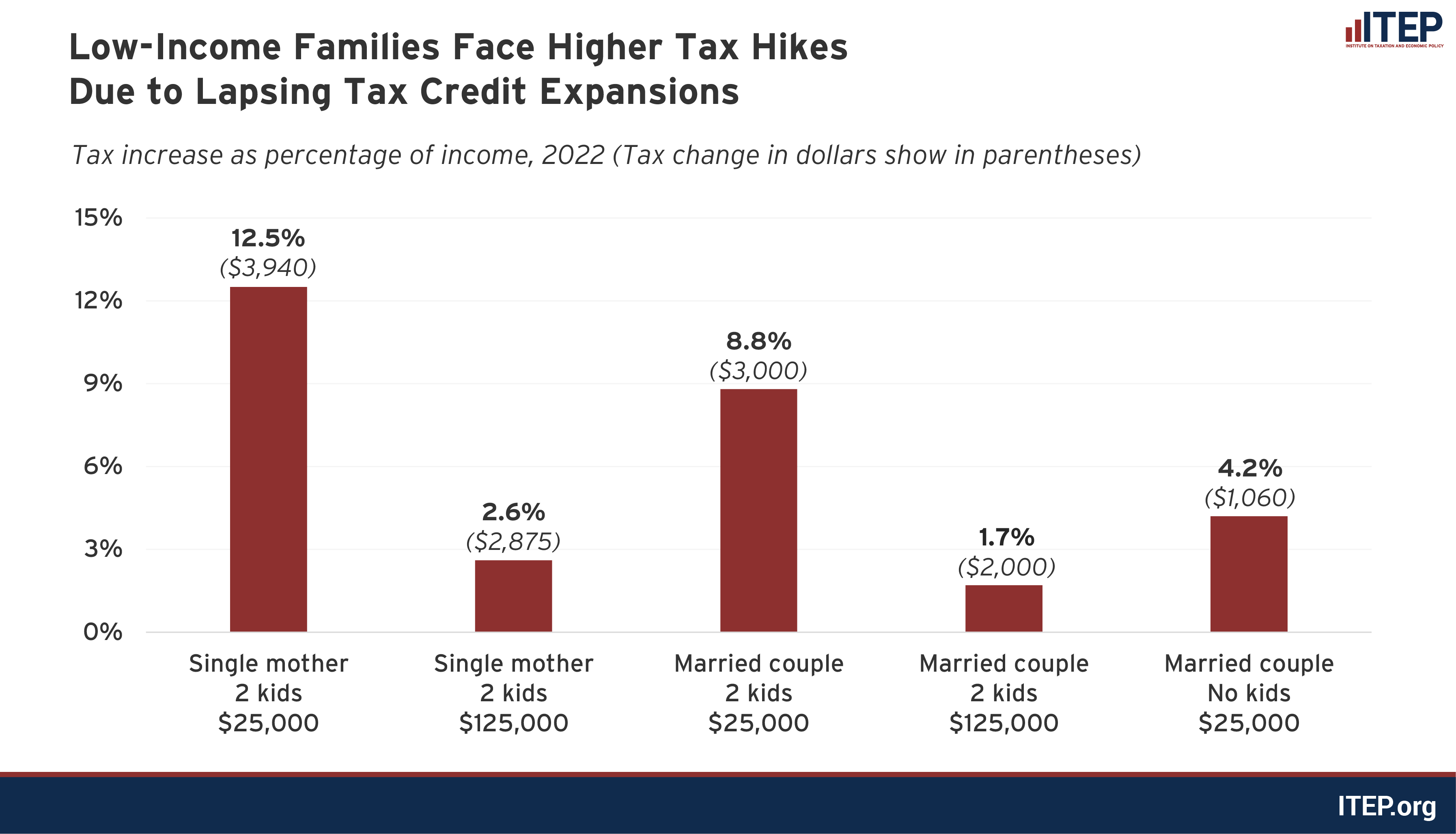

This filing season, a single mother with 2 kids who earned $25,000 owed nearly $4,000 more in taxes than if the CTC enhancement had been extended into 2022. Her after-tax income would have been 12.5 percent higher had Congress made the tax credit expansions permanent. That compares to a tax increase of $2,000—or 1.7 percent of after-tax income—for a married couple with 2 kids earning $125,000.

And although the EITC income limits remained low for childless individuals even with the temporary expansion, a married childless couple earning $25,000 will see a 4.2 percent decrease in their after-tax income due to the lapse.

The CTC and EITC are permanent fixtures of the tax code that provide assistance to low- and middle-income households. Known to be effective programs for income support and poverty reduction, many lawmakers and family advocates had supported their expansion for years. When Congress needed to urgently provide economic assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic, expanding the CTC and EITC were natural choices. As a result, when Americans filed their 2021 taxes a year ago, many received larger tax refunds than they expected due to the credit increases. (Some households also received Economic Impact Payments, or “stimulus checks,” at this time if they had not received them in the mail, further increasing their tax refunds.)

Middle-income families with children benefited from the 2021 increase in the CTC amount from $2,000 per child to $3,600 for children under six and $3,000 for those between six and 17. Lower-income families benefited from the credit increase as well as removal of two limits on the refundable portion of the credit. (Families who earn too little to owe income taxes before credits only benefit from a tax credit if it is refundable, meaning it can result in negative personal income tax liability.) The first limit on the refundable child credit is a rule that caps it at a lower level than the full $2,000 per child. The second limit is a rule capping the refundable credit to a percentage of earned income.

Congress lifted both limits on the refundable Child Credit for 2021, which particularly helped low-income families. The same families also benefited from the credits being distributed each month for the second half of the year, more closely matching a typical household budget than a lump sum tax refund.

Low-income workers without children also benefited from an increase in the EITC in 2021. The EITC—a tax provision designed to provide income assistance while also encouraging participation in the labor force—has been around since the 1970s but has been expanded and restructured through the years. The permanent EITC now mostly benefits workers with children. For 2022, the maximum credit a single individual with no children can receive is $570 and is unavailable if they made more than $16,480. That compares to a maximum credit of $3,733 and an income limit of $43,492 for a single individual with one child. The credit amount and maximum income for childless individuals were both increased in 2021, allowing a maximum credit of $1,502 for childless workers with income limits of $21,430 for single filers and $27,380 for married filers.

While the credit enhancements were enacted as part of the pandemic response package, the results demonstrated that the changes were successful economic policies and should be made permanent. Child poverty was cut nearly in half in 2021—a remarkable success given the economic disruptions during the pandemic. And despite concerns from some lawmakers that the changes would discourage people from entering the workforce, real world labor data from 2021 have repeatedly shown that those concerns did not materialize. The changes in the EITC supported young workers and students and made the credit more closely resemble its original intent—to provide income support and increase the economic security of low-paid workers.

Many lawmakers attempted to extend those expansions. The House-passed Build Back Better Act included a one-year extension of the expanded EITC and a four-year extension of the expanded CTC, but it did not pass the Senate. And more recently, President Biden included both credit expansions in his annual budget proposal. ITEP analyzed the effects of the White House’s CTC expansion plan here.

The credit expansions were good policy. They helped real people, and they lifted the economy. Rather than letting the credits fade into the past, Congress should enact the expansions in the President’s budget proposal.