Revenue-Raising Proposals Provided in Appendix (Jump to Appendix)

The United States needs to raise more tax revenue to fund investments in the American people. This revenue can be obtained with reforms that would require the richest and wealthiest Americans to pay their fair share to support the society that makes their fortunes possible. Different versions of the Build Back Better plans debated over the past several months contain many of these reforms, including proposals from President Biden, a bill approved by the House Ways and Means Committee and another bill passed by the full House of Representatives in late 2021. But the House-passed bill does not have the support of enough members of the Senate to become law. Now, Democrats in both chambers will negotiate and attempt to pass some version of this legislation in the first half of this year. This report places the major revenue-raising proposals discussed during this debate into five categories that each address a specific problem with our tax code. The appendix to this report briefly describes each major revenue-raising proposal.

The United States needs to raise more revenue. It collects and spends far less tax revenue as a share of its economy than other developed countries. The graph below illustrates the revenue collected at all levels of government by countries that are members of the OECD, the countries with which the United States primarily trades with and competes. In 2019, the most recent year for which data are available, the United States collected revenue equal to 25 percent of its gross domestic product (25 percent of its total economic output), while most OECD countries collect more than 34 percent. Only a handful of OECD countries collect less revenue as share of their economies than the United States, and they are all much smaller economies: Costa Rica, Turkey, Ireland, Chile, Columbia, and Mexico.

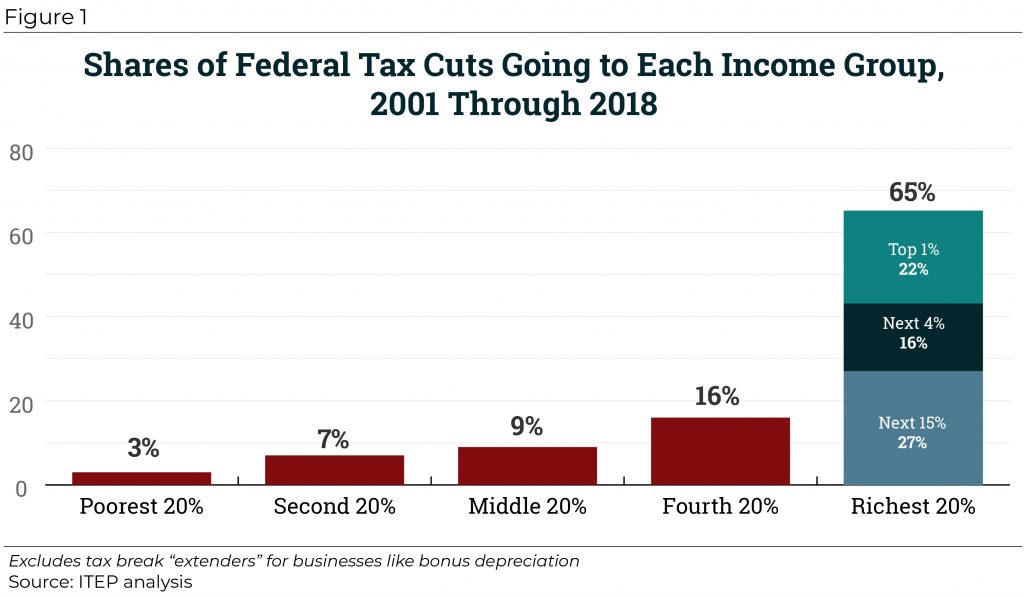

The revenue-raising proposals that have been considered as part of the Build Back Better debate are a dramatic departure from the tax policies enacted by Congress over the past 20 years, most of which have benefited the best-off Americans.[1] At the same time, they would only modestly increase revenue collection as a share of the U.S. economy and put the nation more in line with other developed countries. The proposals that have been discussed mostly fall into five categories.

1. General Proposals to Raise Taxes on High-Income Individuals

First, some are simple, straightforward proposals to raise taxes on individuals most able to pay. For example, the President’s original plan and the bill approved by the House Ways and Means Committee both included a provision to mostly reverse the 2017 tax law’s cut in the top personal income tax rate for “ordinary” income (income that is not capital gains or stock dividends subject to special tax rates). Lawmakers left this provision out of the bill passed out of the full House in November because Sen. Kyrsten Sinema reportedly did not support it, and the bill cannot pass the Senate without the support of every Democratic member. The House bill partly makes up for this by relying more heavily on a surcharge, a simple tax that applies to all types of income above a certain (very high) threshold.

Proposals in this category do not solve deeper problems in our tax code, such as its generous treatment of income from wealth compared to income from work (which is addressed with the next category of proposals). But proposals in this category are relatively easy for the public and lawmakers to understand as reforms that would require the richest and wealthiest Americans to pay their fair share to support the society that makes their fortunes possible. The U.S. tax system currently is not asking that much of our richest citizens. When viewed as a whole, America’s tax system is just barely progressive.

The graph above illustrates the share of total income in the United States flowing to each income group in 2020 as well as the share of total taxes (including federal, state and local taxes) paid by each income group that year. These figures are representative of a normal year because they were generated before economic indicators of the downturn were available and without regard to temporary tax provisions that were eventually enacted (many of which expired at the end of 2021). As the graph illustrates, the richest 1 percent pay a share of total taxes that is only slightly higher than their share of income (about 24 percent v. 22 percent). Analysts measuring the distribution of taxes in other ways have found the nation’s tax system to be even less progressive and have found that the very richest taxpayers pay a lower effective tax rate than others.[2] The tax code could be much more progressive.

2. Proposals to Limit Tax Breaks for Wealth and Income from Wealth

The second category of proposals are designed to ensure that wealth and income from wealth are taxed in a more equitable way. For example, current law allows several income tax breaks for capital gains (profits from selling assets) so that they are taxed less than other types of income. Given that most capital gains flow to the richest Americans, these tax breaks make the tax system far less progressive than it could be. Capital gains are subject to lower tax rates than other income, are not included in taxable income until a taxpayer sells an asset and are forever exempt from the income tax when taxpayers die and pass assets to their heirs. Proposals to address these breaks have appeared over the course of the debate but none were included in the bill passed by the full House. (The surtax proposals do treat capital gains income the same as other income, however.)

Tax breaks for capital gains are one of the most significant obstacles to tax fairness. The most well-known of these breaks is the lower income tax rates for capital gains (and dividends). As illustrated in the graph below, the Congressional Budget Office recently found that nearly all the benefits of this tax break went to the richest 20 percent of Americans in 2019 and three-fourths of the benefits went to the richest 1 percent.

Another proposal in this category would roll back breaks and loopholes in the estate and gift taxes, which are imposed on the transfer of wealth rather than on income from wealth.

3. Proposals to Limit Tax Breaks for Wealthy Business Owners

The tax code provides several unjustified breaks for the owners of pass-through businesses, so called because their profits are not subject to the corporate tax but instead pass through to the owners and are reported on their personal income tax returns. Proponents of these breaks may claim that they help “small businesses,” but most of this income is generated by very large pass-through businesses and most of the benefits of these tax breaks flow to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers.

The most prevalent types of pass-through businesses are partnerships and “S corporations.” There are many very small pass-through businesses in the United States, but most of the business profits go to a small group of very large pass-throughs owned by very well-off people. In 2016, the Joint Committee on Taxation found that while only a quarter of a percent of partnerships reported receipts over $50 million, these companies reported 72 percent of aggregate partnership receipts. Likewise, less than half a percent of S corporations reported receipts over this threshold, but this small percentage collected 40 percent of all S corporation receipts.

Nonetheless, Congress has enacted several tax breaks for owners of these businesses. One of the largest is the special 20 percent deduction for “qualified business income,” meaning profits individuals receive from pass-through companies that they own. As illustrated in the graph below, the Congressional Budget Office recently found that 88 percent of the benefits of this tax break went to the richest 20 percent of Americans in 2019 and half the benefits went to the richest 1 percent.

Several proposals discussed as part of the Build Back Better debate would limit certain tax breaks for pass-through business owners.

4. General Proposals to Raise Taxes on Corporations

The fourth category of proposals are designed to ensure that corporate profits do not escape taxation. Corporate profits are a type of income from wealth that indirectly flows to the (mostly) wealthy owners of corporate stocks. The most straightforward proposal in this category would partly reverse the 2017 tax law’s cut in the statutory income tax rate for corporations, which was previously 35 percent. The president’s plan and the Ways and Means Committee bill include different versions of this proposal, but the full House left it out of the bill, reportedly because of Sen. Sinema’s opposition. The House bill makes up most of the revenue with a corporate minimum tax and a surtax on stock buybacks, two provisions were not included in the version approved by the Ways and Means Committee.

Low corporate taxes are often justified as a way to keep American corporations competitive, but there is no evidence that corporate taxes have hindered competitiveness or that corporate tax cuts improved competitiveness. The United States accounts for just over 4 percent of the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP, but American corporations account for 40 percent of the market value and a third of the sales of the Forbes Global 2000, which is an annual list that measures the largest businesses in the world based on sales, profits, assets, and market value. These figures were essentially the same in 2017, before Congress dramatically cut the corporate tax, and in 2020, as illustrated in the table below.[3]

5. Proposals to Limit Tax Breaks for Corporate Profit-Shifting and Offshoring

Most of the remaining corporate tax proposals address the international corporate tax rules and eliminate or reduce incentives for companies to shift profits offshore or to shift real operations and jobs offshore. The current rules that tax offshore profits more lightly than domestic profits encourage American corporations to use accounting gimmicks to make their profits appear to be earned in countries with no corporate tax or a very low corporate tax.

It is easy to demonstrate that this is happening. The graph below illustrates the profits that American corporations claimed to earn in 2018 through their offshore subsidiaries in 15 countries where these claims seem suspicious or, in some cases, impossible. For example, in 2018 American corporations reported $97 billion in profits in Bermuda, a small island nation with a gross domestic product (GDP) of $7 billion that year. In other words, U.S. multinational corporations claimed to earn more than 13 times the GDP of Bermuda in Bermuda in 2018.

The proposals in this category would eliminate most, but not all, of these problems and would implement new international agreements brokered by the United States to prevent corporate tax-dodging.

Appendix: Revenue-Raising Proposals Discussed During Build Back Better Debate

The following provides a list and description of some key revenue-raising proposals that have been included in different versions of the Build Back Better agenda. Unless otherwise noted, the revenue impact of each proposal is taken from the estimates of the bills provided by Congress’s official revenue-estimators, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).[4] Note that the revenue impact of most of these proposals is taken from estimates that assume they are enacted as part of a package of proposals that interact with each other in complicated ways. The revenue impact of each proposal could be very different if enacted on its own or in combination with different proposals.

General Proposals to Raise Taxes on High-Income Individuals

Raise the top personal income tax rate for “ordinary” income from 37 percent to 39.6 percent.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $170.5 billion

- Status: Included in Ways and Means Committee bill but left out of House-passed bill.

-

- The tax law enacted by Congress and President Trump at the end of 2017 cut the top personal income tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent. This provision in the Ways and Means bill would reverse that cut and adjust the top bracket so that it starts at taxable income of $450,000 for married couples, $425,000 for single parents, and $400,000 for singles. This provision would raise revenue mainly from 2022 through 2025, the years when the personal income tax cuts are in effect under the 2017 tax law.

Create a surcharge on very high levels of adjusted gross income.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $127.3 billion under the Ways and Means Committee bill, $227.8 billion under the House-passed bill

- Status: Different versions in Ways and Means Committee bill and House-passed bill.

-

- While this proposal does not close any special breaks or plug the convoluted loopholes used by high-income people, it does create a new tax that is relatively simple and that applies to most types of income of the very rich at the same rates. The Ways and Means Committee bill would create a 3 percent surcharge on adjusted gross income (AGI) in excess of $5 million. The bill passed by the full House would impose a surtax of 5 percent on AGI between $10 million and $25 million and 8 percent on AGI exceeding $25 million.

Proposals to Limit Tax Breaks for Wealth and Income from Wealth

Partly repeal the special, lower personal income tax rate for certain income from wealth (long-term capital gains and stock dividends).

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $123.4 billion

- Status: Included in Ways and Means Committee bill but left out of House-passed bill.

-

- Currently, capital gains (profits from selling assets) and stock dividends are subject to the personal income tax at much lower rates than other types of income, with a top rate of just 20 percent. Most of the benefits of the special rates for capital gains and dividends go to the richest one percent. As a result, some very well-off individuals pay a lower effective tax rate than taxpayers whose incomes are much smaller. The Ways and Means bill would raise this top rate to 25 percent.

End the exclusion of capital gains on assets left to heirs for gains exceeding $1 million ($2 million for married couples).

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $322.5 in combination with proposal to partly end special rate for capital gains[5]

- Status: Not included in either the Ways and Means Committee bill or the House-passed bill (but included in the President’s plan).

-

- This proposal would dramatically restrict the “stepped up basis” tax break that wealthy families use to avoid paying taxes on capital gains. In the eyes of economists, any increase in the value of assets is income to the owner of those assets. But the tax code only taxes that income when assets are sold and the increase in value becomes a “realized” capital gain. Under current law, if a taxpayer dies and passes assets to heirs, the “unrealized” capital gains on those assets is excluded from income and will never be taxed. To calculate a capital gain after selling an asset, the “basis,” which is usually the price the taxpayer paid to purchase the asset, is subtracted from the sale price they received for the asset. For heirs, the basis is “stepped up” to the asset’s value on the day they inherited it, effectively wiping out all gains on the assets before they inherited it.

- In addition to proposing to partly repeal the lower tax rate for capital gains, the President also proposed to restrict the stepped-up basis tax break, which wealthy taxpayers could otherwise use to avoid the rate increase on capital gains.

Restrict the rule allowing deferral of income tax on capital gains until assets are sold (for billionaires).

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $557 billion[6]

- Status: Not included in either the Ways and Means Committee bill or the House-passed bill (but proposed by Sen. Ron Wyden as the Billionaire’s Income Tax).

-

- Under the current rules, capital gains are only included in income for tax purposes when an asset is sold and the gains are “realized,” which means the seller profits from an asset sale. Unrealized capital gains are not taxed, meaning a person who owns an asset that is worth more and more each year can defer paying income taxes on the appreciation until they sell the asset. Unrealized capital gains are the main type of income for some very wealthy people, who can defer paying income taxes on it for years, allowing their wealth to grow much more rapidly than the wealth a middle-class person might put in a savings account where the income it generates (the interest paid on the account) is taxed each year. Sen. Ron Wyden, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, has proposed a “Billionaires Income Tax,” which would shut down deferral of income tax on unrealized capital gains, albeit only for billionaires. Wyden’s approach is also sometimes called “mark-to-market" taxation.

Repeal several breaks in the estate tax.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: (combined) $82 billion

- Status: Included in Ways and Means Committee bill but left out of House-passed bill.

-

- Most revenue-raising proposals discussed during this debate would increase taxes on income from wealth or other income. But the Ways and Means Committee bill also included a group of proposals that would change the estate and gift taxes used by the federal government to tax wealth itself (or, technically, the transfer of wealth). Most important in the short run, the Ways and Means bill would repeal the 2017 tax law’s provision that doubled the exemption from the estate tax, which is in effect through 2025 under current law. For example, under the 2017 law the estate tax exempts roughly (at least) the first $12 million of assets for single taxpayers and $24 million for married couples in 2022. These exemptions would fall back to $6 million for singles and $12 million for married couples under the Ways and Means bill, which would raise $54 billion over ten years, mainly from 2022 through 2025 when the 2017 law is in effect.

- Another provision in the Ways and Means bill would clamp down on the practice of wealthy people placing their assets in a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT) that gives the assets right back to them after a couple of years to avoid paying taxes on any increase in the assets’ value. Still another provision would address “valuation discounts,” restrictions placed on assets owned by family members which are claimed, falsely, to reduce the value of the estate.

Proposals to Limit Tax Breaks for Wealthy Business Owners

Repeal an exception in the 3.8 percent net investment income tax.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $252.2 billion

Status: Included in both the Ways and Means Committee bill and the House-passed bill.

-

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA) added a 3.8 percent bracket to the Medicare payroll tax for high-earners and created a 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT) so that high-income people would generally pay 3.8 percent of their income whether it comes from work or wealth. But a loophole allows certain active profits from pass-through businesses to escape both taxes. The Ways and Means bill and the House-passed bill would close this loophole but would phase in the effect of this reform for people with adjusted gross income between $400,000 and $500,000 in the case of an unmarried person and between $500,000 and $600,000 in the case of a married couple.

Limit the 20 percent deduction for pass-through business income under sec. 199A.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $78 billion

Status: Included in Ways and Means Committee bill but left out of House-passed bill.

-

- Pass-throughs are businesses whose profits are reported on the personal tax returns of the owners and not subject to the corporate income tax. The tax law enacted by Congress and President Trump at the end of 2017 includes a new 20 percent deduction for income from pass-through businesses. Proponents of this deduction may describe it as helping small businesses, but most of its benefits go to the richest one percent and to the owners of very large businesses. The Ways and Means bill would not phase the deduction out even for high-income people (as President Biden has proposed) but instead would limit the total amount of the deduction to $500,000 for married couples and $400,000 for unmarried people. This would raise revenue mainly from 2022 through 2025, the years when the personal income tax cuts are in effect under the 2017 tax law.

Make permanent the limit on pass-through business losses.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $160 to $168 billion

- Status: Included in both the Ways and Means Committee bill and the House-passed bill.

-

- Under rules enacted in 2017, when business owners report losses, they cannot use these losses to offset more than $250,000 of their non-business income (or $500,000 of non-business income in the case of married couples). This prevents high-income taxpayers from deducting business losses that exist on paper only to reduce the other income they report to the IRS. One of the rare provisions in the 2017 tax law that looks good in retrospect, the limit on pass-through losses was set to expire with most of the other personal income tax changes after 2025. The CARES Act controversially suspended it for 2020 and retroactively for 2018 and 2019. The American Rescue Plan Act extended it for one year, through 2026. This provision would make the limit stricter by imposing the $250,000/$500,000 limit on excess losses even after the year when those losses are reported and would also make the limit permanent.

General Proposals to Raise Taxes on Corporations

Partly reverse the corporate tax rate cut in the 2017 tax law.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $540.1 billion

- Status: Included in Ways and Means Committee bill but left out of House-passed bill.

-

- The tax law enacted by Congress and President Trump at the end of 2017 cut the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. The Way and Means Committee bill would increase the rate from 21 percent to 26.5 percent, well below the previous level of 35 percent.

Corporate Minimum Tax.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $318.9 billion

- Status: Included in the House-passed bill but not the Ways and Means Committee bill.

-

- This provision would ensure that the roughly 200 biggest corporations pay federal income taxes equal to at least 15 percent of the profits that they report to shareholders. These companies are technically subject to the 21 percent statutory corporate tax rate, but under current tax rules they often pay little or nothing. This provision would only apply to corporations with profits exceeding $1 billion annually (based on average profits of each company over the past three years). The minimum tax of 15 percent would apply to corporations’ “book” income, meaning the profits they report to the public and to investors. Corporations would pay whichever is more, their tax liability under the regular corporate tax rules or 15 percent of their worldwide book profits.

Excise Tax on Stock Buybacks.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: $124.2 billion

- Status: Included in the House-passed bill but not the Ways and Means Committee bill.

-

- Another provision in the bill would create an excise tax to remove tax advantages for corporations that transfer profits to their shareholders through stock buybacks rather than dividends. Corporations can shift their profits to shareholders either by paying them stock dividends or by buying their own stocks, which increases the value of the stocks held by shareholders. Shareholders pay income tax on stock dividends (though often at lower rates than wages and salary income). Stock buybacks, on the other hand, result in capital gains (because they increase the value of the stocks) that may not be taxed for years and in many cases are never taxed at all. Under this provision, corporations would be required to pay a tax equal to 1 percent of their stock repurchases, ensuring that profits shifted to shareholders in this way are subject to some federal tax.

Proposals to Limit Tax Breaks for Corporate Profit-Shifting and Offshoring

Combined proposals to reform the international corporate tax rules.

- 10-Year Revenue Impact: (all relevant proposals combined) $300 billion under the Ways and Means Committee bill, $279 billion under the bill passed by the full House.

- Status: Somewhat different versions included in the Ways and Means Committee bill and the House-passed bill.

-

- The bills include several provisions that would reduce tax breaks for offshore profits of American corporations and tax breaks for foreign corporations operating in the U.S. The list of provisions reforming international corporate tax rules is long, but here are a few of the most important:

- Reduction in exemption for offshore profits for so-called “Qualified Business Asset Investments” (QBAI)

This provision would reduce an incentive under current law for corporations to shift profits, as well as real operations and jobs, offshore. Under current law, some offshore profits of American corporations are not taxed because they fall within the QBAI exclusion (equal to a 10 percent return on tangible offshore investments). The Ways and Means and House bills would reduce this break but not eliminate it. Offshore profits would still be excluded except to the extent that they exceed 5 percent (down from 10 percent) of a company’s tangible offshore investments. The bills could therefore preserve some of the incentive for companies to invest offshore rather than in the U.S. to shield some of their offshore profits from U.S. taxes. This is an improvement over current law, but the better option would be the president’s proposal to repeal the QBAI exclusion altogether. - Increase the minimum effective tax rate on offshore corporate profits.

Under current law, when offshore profits of American corporations are subject to U.S. taxes, they generally are subject to a rate of 10.5 percent, just half the rate that applies to domestic profits, which means offshore profits are more advantageous than domestic profits. The House bill would ensure that these offshore profits would be taxed at a combined rate (including both U.S. taxes and foreign taxes) of at least 15 percent. This provision would implement part of an international agreement brokered by the Biden administration to ensure that almost all corporate profits worldwide are taxed at a rate of at least 15 percent. This is a watered-down version of previous proposals. These profits would be taxed at a rate of at least 16.6 percent under the Ways and Means and 21 percent under the Biden administration’s original proposal. - Apply the minimum tax rate for offshore profits on a per-country basis.

American corporations receive tax credits against their U.S. taxes for taxes they pay to other countries where they do business. These foreign tax credits (FTCs) ensure that profits are not double-taxed. But under the current rules, when American corporations pay taxes in foreign countries that are even higher than the U.S. taxes that would otherwise apply, they can use their “excess” FTCs to offset U.S. taxes on profits generated in countries with low taxes or no corporate tax at all. In other words, the current rules allow American corporations to use FTCs in ways that are overly generous and beyond what is necessary to prevent double-taxation. The Ways and Means Committee bill and the bill passed by the full House would prevent this by applying FTC per-country, meaning excess FTCs that a corporation generates for one country cannot be used to shield profits it claims to earn in another country that is a tax haven.

- Reduction in exemption for offshore profits for so-called “Qualified Business Asset Investments” (QBAI)

- The bills include several provisions that would reduce tax breaks for offshore profits of American corporations and tax breaks for foreign corporations operating in the U.S. The list of provisions reforming international corporate tax rules is long, but here are a few of the most important:

[1] Steve Wamhoff and Matthew Gardner, “Federal Tax Cuts in the Bush, Obama, and Trump Years,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 11, 2018. https://itep.org/federal-tax-cuts-in-the-bush-obama-and-trump-years/

[2] Steve Wamhoff, “Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman’s New Book Reminds Us that Tax Injustice Is a Choice,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 15, 2019. https://itep.org/emmanuel-saez-and-gabriel-zucmans-new-book-reminds-us-that-tax-injustice-is-a-choice/

[3] 2017 data is reported in the 2018 edition of the Forbes Global 2000. 2020 data is reported in the 2021 edition of the Forbes Global 2000.

[4] JCT published a revenue-estimate on September 13, 2021, of the version of the bill approved by the House Ways and Means Committee. That estimate can be found here: https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-42-21/. On November 19, 2021, JCT published a revenue estimate of the bill that was then passed by the House of Representatives. That estimate can be found here: https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-46-21/

[5] Department of the Treasury, General Explanations of the Administration's Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals, May 2021. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2022.pdf

[6] Senate Committee on Finance, Wyden Statement on Billionaires Income Tax Score, November 5, 2021. https://www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/wyden-statement-on-billionaires-income-tax-score