Introduction

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) radically changed the international tax system. It slashed taxes on corporate income, both domestic and foreign. It encouraged U.S. multinational corporations to shift jobs, profits, and tangible property abroad, and keep intangibles home. This report describes the new international tax system—and its many gaps—and also provides a road map for how to fix these gaps and surveys recent legislative approaches.

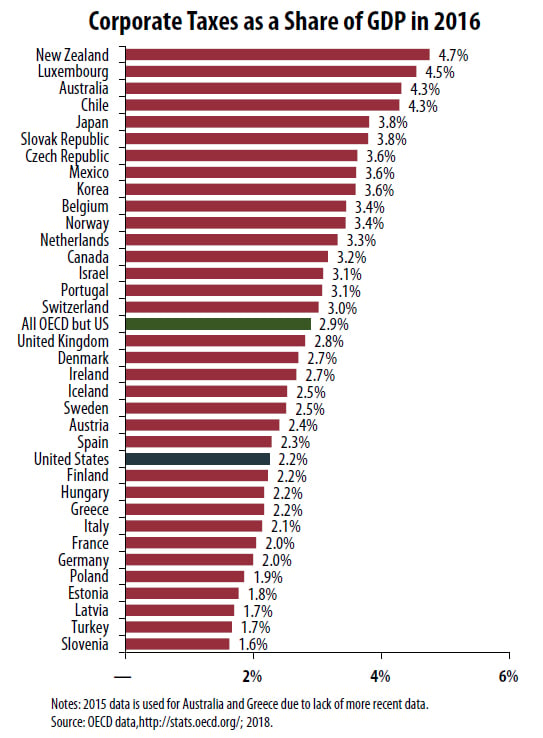

For many years, multinational corporations and their lobbyists claimed that the U.S. tax system was “uncompetitive” because it taxed corporations at 35 percent and applied that tax rate to income earned worldwide.[i] But this criticism only told half the story. While the nation’s statutory tax rate was high, a myriad of tax breaks and loopholes in the code translated to a much lower effective rate. In fact, a study by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) found that from 2008-2015, profitable Fortune 500 companies paid an average federal tax rate of 21.2 percent, with many companies paying nothing at all.[ii] Indeed, before the new tax law, the percentage of U.S. corporate taxes as a share of GDP was substantially below the OECD average.[iii]

Similarly, the nation didn’t meaningfully have a worldwide tax system. Under the previous law, the United States only nominally taxed corporations’ offshore earnings, minus foreign taxes already paid. The reason that the U.S. could be said to only “nominally” have a worldwide system is that the law allowed companies to indefinitely defer paying taxes on earnings from their foreign subsidiaries and there was no legal obligation for foreign subsidiaries to pay dividends, which would trigger U.S. taxes. So, companies openly stockpiled their foreign earnings in tax havens. Allowing companies to indefinitely avoid paying taxes on their offshore earnings made the federal tax system economically similar to a territorial tax system in that many companies ended up paying little or nothing on much of their offshore earnings.[iv]

The opportunity to avoid taxes on offshore profits also encouraged multinational corporations to shift profits into tax havens through accounting tricks and loopholes and then keep those profits there (on paper at least). The system also created an incentive to move operations into low-taxed jurisdictions. As a result, U.S. companies held an astounding $2.6 trillion in profits offshore[v] and avoided an estimated $100 billion annually in taxes through offshore tax avoidance.[vi]

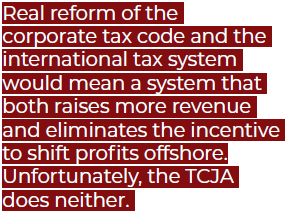

Real reform of the corporate tax code and the international tax system would mean a system that both raises more revenue and eliminates the incentive to shift profits offshore.[vii] Unfortunately, the TCJA does neither. It cut corporate taxes by more than $700 billion over the next decade, largely through reducing the statutory rate from 35 to 21 percent, while at the same time creating new opportunities for corporations to exploit the tax system.

Real reform of the corporate tax code and the international tax system would mean a system that both raises more revenue and eliminates the incentive to shift profits offshore.[vii] Unfortunately, the TCJA does neither. It cut corporate taxes by more than $700 billion over the next decade, largely through reducing the statutory rate from 35 to 21 percent, while at the same time creating new opportunities for corporations to exploit the tax system.

Time will tell how effective or damaging the changes are, but early indications are not good. Aside from a substantial increase in complexity, the initial estimates from the non-partisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) indicate that rather than raising revenue, the international provisions (excluding one-time revenue from the repatriation)[viii] will decrease revenue by $14.4 billion over the next 10 years.[ix] In other words, rather than raising revenue from the $100 billion lost each year from international tax avoidance, the international provisions give away more revenue to multinational corporations. In addition, a recent analysis by the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) noted that the new law will continue to allow companies to avoid taxes on hundreds of billions of dollars in offshore income, while at the same time creating a significant new tax incentive for companies to shift jobs and profits offshore.[x]

These non-partisan analyses make it clear that the TCJA’s international provisions need substantial reform. The first section of this report highlights how the new international provisions work and the issues they create. The second section of the report examines a series of reforms to improve the fairness and efficiency of the international tax system.

Part 1: The New International Tax System

A. Overview of the New International Tax System

Moving to a Territorial Tax System

Theoretically, the major international change of the TCJA is that it shifts the United States from a worldwide to a territorial corporate tax system.[xi] Under a pure territorial tax system, U.S. companies would owe no taxes on their offshore earnings. The new tax law moves in this direction by exempting from taxation earnings repatriated to the United States from foreign subsidiaries (also known as a 100 percent dividend exemption). This change loses more revenue than any other change in the international portion of the tax law ($223.6 billion over the next 10 years).[xii]

At the same time, and despite the new law’s territorial framework, the law requires U.S. companies to pay a tax immediately on a portion of their offshore earnings determined to be “global intangible low tax income” or GILTI (discussed below). The drafters of the new law understood multinationals would, otherwise, shift profits to offshore tax havens. In addition, the new tax law maintains the existing Subpart F rules, which require the immediate taxation of certain highly mobile income such as royalties, dividends, and interest (as well as some limited active business income). In other words, it created a hybrid of the worldwide and territorial systems in which repatriation is tax-free, but certain foreign profits are subject immediately to a minimum level of taxation in the hands of the U.S. shareholder.

The TCJA also adopted an anti-abuse rule, designed to limit the stripping of income from the U.S. to foreign affiliates, the Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax or BEAT (discussed below). Unfortunately, these steps are likely to be ineffective in practice and will lead to continued profit shifting and international tax avoidance.

Transition Tax on Accumulated Offshore Earnings

Under previous law, companies could defer paying U.S. taxes on offshore earnings as long as they did not technically repatriate those earnings (either by paying a dividend or what the law deemed to be a dividend). This rule drove companies to stash an estimated $2.6 trillion in untaxed earnings offshore (on paper at least).[xiii] As part of its transition to the new tax system under which companies’ repatriation of offshore income is tax-free, the TCJA deemed all accumulated unrepatriated earnings immediately taxable at a rate substantially lower than the 35 percent rate they previously would have owed upon repatriation. For all earnings held in cash or cash equivalents, companies are required to pay a rate of 15.5 percent. For all earnings held in illiquid assets, companies are required to pay a rate of 8 percent. These effective tax rates are created by providing a deduction of 22.9 percent for liquid assets and 44.3 percent for illiquid assets.

Companies can reduce the transition taxes they owe with foreign tax credits generated by previous taxes that they’ve paid, but their foreign tax credits are reduced proportionately (44.3 percent allowed for cash and 22.9 percent for non-cash).

Companies owing the transition tax can pay the tax interest-free in installments over a period of eight years. In the first five years the installments are 8 percent of the total each year, in year six 15 percent, in year seven 20 percent, and in year eight 25 percent. Allowing companies to defer paying the full tax over 8 years represents a substantial discount on their real tax rate given the time value of money—on top of the huge tax benefits many companies have received from postponing tax on these profits in the years since they were earned.[xiv]

This huge stash of offshore cash represented an important short-term option for making corporate tax reform somewhat more affordable—but the new law fails to take full advantage of this option. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy has estimated that companies previously owed more than $750 billion on their offshore earnings. Given that the JCT expects that the transition tax will raise $338.8 billion in revenue,[xv] this means the transition tax provides a tax windfall of more than $400 billion to those companies who held their earnings offshore to avoid taxes.[xvi] This $400 billion, of course, is significantly understated when the time-value interest benefit to companies of the back-ended payment of the $338.8 billion is considered. In one of many budget gimmicks, lawmakers used the revenue from the transition tax to pay for the cost of long term tax cuts, even though the revenue generated is only a one-time benefit and the cost of the other permanent corporate tax cuts will be ongoing.

B. Components of the New International Tax System

Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI)

The goal of the tax on so-called global intangible low-taxed income or GILTI is to ensure that foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies with excess returns on their offshore investments pay some minimum level of tax. This provision and the Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT discussed below) were the two major provisions that were created to help combat tax avoidance and generate revenue to offset the cost of the move to a territorial tax system. Unfortunately, they both will likely fall short of their intended purpose.

What exactly is GILTI? GILTI is the income the foreign subsidiary of a U.S. company earns in excess of 10 percent of the subsidiary’s specified tangible assets (technically, the tax “basis” of the assets, which may decline somewhat over time). For example, a company with $500 of earnings and $1,000 in specified tangible assets would have GILTI of $400 (the excess of $500 over 10 percent of $1,000). The idea behind this approach is to only tax foreign income that constitutes an excessively high return on investment, rather than a more typical return on investment. To be clear, while the name “global intangible low tax income” implies that this income is exclusively intangible income, GILTI includes all income, with few exceptions, over the 10 percent of specified tangible asset threshold.[xvii] In addition, GILTI also may not count all intangible income, because of serious flaws in its formulation.

What exactly is GILTI? GILTI is the income the foreign subsidiary of a U.S. company earns in excess of 10 percent of the subsidiary’s specified tangible assets (technically, the tax “basis” of the assets, which may decline somewhat over time). For example, a company with $500 of earnings and $1,000 in specified tangible assets would have GILTI of $400 (the excess of $500 over 10 percent of $1,000). The idea behind this approach is to only tax foreign income that constitutes an excessively high return on investment, rather than a more typical return on investment. To be clear, while the name “global intangible low tax income” implies that this income is exclusively intangible income, GILTI includes all income, with few exceptions, over the 10 percent of specified tangible asset threshold.[xvii] In addition, GILTI also may not count all intangible income, because of serious flaws in its formulation.

Exempting 10 percent of specified tangible asset mechanism creates three significant problems. First, only taxing GILTI could allow many companies to pay nothing on offshore profits as long as their profits are lower than 10 percent of tangible offshore assets. Second, it creates a substantial incentive for companies to move tangible assets offshore to increase the 10 percent base not subject to GILTI taxation. This is the reasoning behind the CBO’s analysis saying that the provision “may increase corporations’ incentive to locate tangible assets abroad.”[xviii] Finally, to the extent that the goal is to tax only excess returns, the 10 percent rate likely will be well above the rate needed to accomplish this goal given that the typical normal rate of return on investment is much lower than 10 percent.[xix]

After determining the level of GILTI by subtracting the 10 percent of tangible assets, the TCJA technically applies the full 21 percent corporate tax rate, but with a 50 percent deduction on these earnings, making the effective rate on GILTI 10.5 percent. In addition, companies can apply foreign tax credits to reduce the resulting tax liability. These foreign tax credits are applied at 80 percent of their value. Because of the reduction of the value of foreign tax credits, a company would need to pay a foreign tax rate of 13.125 percent (13.125% x 80% = 10.5%) to guarantee that it owes no residual U.S. tax.

Unlike some previous foreign minimum tax proposals, the TCJA’s tax on GILTI allows foreign tax credits to be applied on a worldwide basis. This will continue the game playing of “cross-crediting” because it allows companies to use excess foreign tax credits generated in higher tax countries to offset using taxes owed in low- or zero-tax countries.[xx]

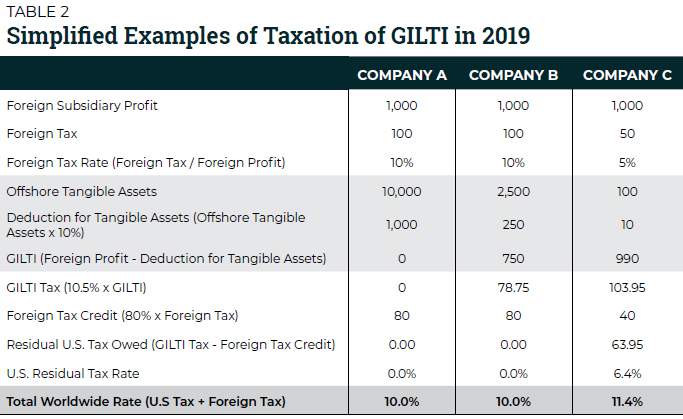

To understand how the tax on GILTI could apply in practice, it’s worth exploring the calculation examples in the table above. For Company A, its $10,000 in offshore tangible assets mean that it can exclude $1,000 of foreign profits in calculating its GILTI. Since the company only has $1,000 in foreign profits, it therefore has $0 in GILTI and, thus, has no profits for the residual tax to apply to.

In contrast, Company B has $2,500 in offshore tangible assets, which means it can exclude $250 from GILTI. Given its $1,000 in profits, the company therefore has $750 in GILTI. The tax owed on GILTI is 10.5 percent, so the company has $78.75 in tax liability before considering its foreign tax credits. Because Company B has paid $100 in foreign taxes, it has $80 in foreign tax credits that can be applied to reduce its GILTI liability and because the company only owes $78.75 in GILTI taxes, the foreign tax credit in this case would completely wipe out the residual tax owed.

Company C has $100 in offshore tangible assets and $1,000 in foreign profits, meaning that it starts off with a GILTI liability of $103.95. Company C has only paid a foreign tax of $50, meaning that it has only $40 of foreign tax credits. This means that the residual tax it would owe to the United States would be $63.95 or an additional tax of 6.4 percent. Overall, Company C’s worldwide tax rate (foreign plus the residual U.S. tax) would total 11.4 percent under this scenario.

There are several key points to take away from these hypothetical, but plausible, scenarios. First, despite being portrayed as a minimum tax of 10.5 percent, the combination of the application of foreign tax credits and the 10 percent base of offshore tangible assets guarantee that many companies will end up paying much lower rates or even nothing on their offshore earnings. Second, the fact that companies can end up paying a rate of less than half the U.S. rate of 21 percent imposed on domestic profits creates a significant tax incentive for companies to shift their profits, on paper at least, offshore. Third, to the extent that tax rates matter, the lower tax rate on offshore income also creates an incentive to move real jobs and operations offshore to obtain a lower tax rate.

Over the first 10 years of the TCJA, the tax on GILTI is estimated to raise $112.4 billion in revenue.[xxi] To help offset the long-term cost of the TCJA, the deduction for GILTI is decreased from 50 percent to 37.5 percent in 2026, meaning that the effective rate on GILTI will go from 10.5% to 13.125%.

Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII)

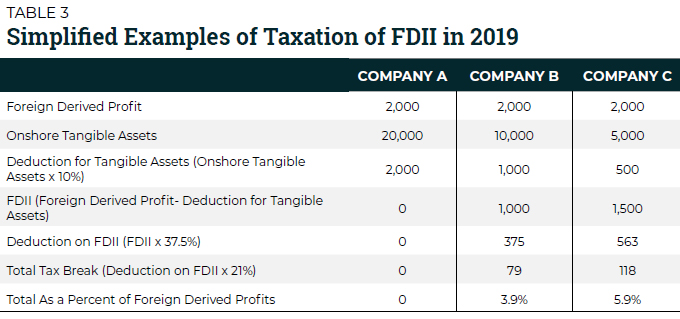

If GILTI is meant to be the stick to prevent companies from profit shifting, the tax break on foreign derived intangible income (FDII) is supposed to be the carrot to encourage companies to increase their business operations and use their intangible assets within the United States. The idea is that companies will receive a tax break on domestic profits they earn in the United States from sales abroad. Under the new policy, income defined as FDII receives a deduction of 37.5 percent, which means the effective tax rate on this income would be 13.125 percent.

What constitutes FDII? Following the pattern set by the GILTI definition, FDII is defined as domestic profits earned from sales abroad above 10 percent of a companies’ specified U.S. tangible assets. Once again, the break is not limited to intangible income. For example, if a company has $10,000 in tangible assets in the United States and $2,000 in foreign derived profits, then it would have $1,000 in FDII eligible for the 37.5 percent deduction. It is worth noting that because in the case of FDII having more tangible assets in the United States means a smaller tax break, this provision further exacerbates the incentive for companies to move their tangible assets offshore to lower their taxes.

The FDII may not be effective in encouraging companies to relocate their intangible assets, or operations that use intangible assets to the United States. Foreign companies still have an even greater incentive to locate their intangible assets in tax haven countries where they can pay single digit tax rates or nothing at all on their intangible income. In practice, the FDII rate would only equal or be more beneficial than the GILTI rate if the U.S. company has zero specified tangible assets and the foreign company was paying a foreign tax rate of 13.125 percent or higher.

The FDII also appears ripe for abuse. Companies could attempt to expand the scope of the break outside the original intent of the TCJA by selling their products to separate foreign distributors that then sell back the items into the United States. This action would essentially turn domestic income into export income that could potentially receive the lower tax rate.[xxii]

If the FDII provision is unlikely to attract a significant amount of new business operations and intangible assets to the United States, then it should be seen less as an incentive and more as a windfall to those export oriented domestic companies and multinationals that have held intangibles domestically and conducted operations in the United States for years.

In addition, the FDII’s long term efficacy is dubious because it likely violates World Trade Organization (WTO) rules against subsidizing exports.[xxiii] In fact, the Tax Commissioner for the European Commission has already said that the European Union is likely to challenge the provision at the WTO.[xxiv] A successful WTO challenge would mean either the United States would have to eliminate the provision or face retaliatory trade measures.

Over the first 10 years of the TCJA, the FDII is estimated to lose $63.8 billion in revenue.[xxv] To help offset the long-term cost of the TCJA, the FDII deduction is reduced from 37.5 percent to 21.875 percent in 2026, meaning that the effective rate on FDII will go from 13.125% to 16.406%.

Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT)

The Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax, or BEAT, is an alternative minimum tax created with the intention of preventing multinational companies from using various payments such as interest, royalties, rents, service fees, etc. to shift their profits out of the United States. To determine whether a company has liability under the BEAT, it adds back to its taxable income the deductions it took for certain payments to its related foreign companies. If 10 percent of this total exceeds the taxes already paid on its taxable income, then it pays the difference.

For example, assume that Company A has taxable income of $1,000 and a regular corporate tax bill of $210 (21 percent) and deductible payments to a foreign subsidiary of $1,500 for royalties. Under the BEAT, the company would add back the $1,500 in royalties and multiply the result ($2,500) by 10 percent. The resulting tax would be $250, which is higher than the regular corporate tax liability of $210. The company owes an additional $40 in taxes.

Like the FDII, the BEAT appears to invite various tax-minimization strategies that could sharply limit its effectiveness. The BEAT does not apply to companies with gross receipts that average under $500 million over three years, a level that exempts a significant number of multinational corporations from the tax and creates a significant incentive for companies to stay just under the threshold. In addition, it only applies to companies whose tax benefits from base erosion exceed 3 percent of their overall deductions, again allowing many companies to avoid the tax and creating a significant incentive to manipulate their deductions to avoid crossing the threshold. Finally, the deductible payments targeted by the BEAT do not include cost of goods sold, which could allow companies to package their royalties with cost of goods sold and avoid triggering BEAT liability.[xxvi]

Also like the FDII, the BEAT potentially conflicts with WTO rules and tax treaties by imposing what may be a discriminatory tax on certain income.[xxvii]

For all its flaws, the BEAT remains the most significant international anti-base erosion measure in the new law, which is reflected by the fact that the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that the BEAT will raise $149.6 billion in revenue over the next 10 years.[xxviii] The applicable tax rate for the BEAT is 5 percent in 2018, 10 percent for 2019-2025, and 12.5 percent after 2025.

Part 2: Reforming the International Tax System

Given the state of the international provisions within the tax code created by the TCJA, what is needed now is a new tax reform effort that seeks to make the system fair and ends rampant international tax avoidance. To achieve these goals, international tax reform should embrace the following three broad policies.

- Equalize the Rates: Congress should equalize the rates so that companies based in the United States pay the same tax rate on their offshore earnings as they do on their domestic earnings.

- Eliminate Inversions: Congress should enact provisions that will eliminate the incentive and ability of companies to reincorporate offshore to avoid taxes.

- Create Transparency: Congress should require companies to publicly disclose basic tax, income, and other financial information on a country-by-country basis.

Three Next Steps for Tax Reform: Equalize the Rates, Eliminate Inversions, Create Transparency

Equalize the Rates

As discussed above, there are a number of ways in which the new international tax system provides tax advantages to different forms of offshore income. The straightforward way of preventing this is to require U.S companies to pay the same tax rate on their foreign and domestic earnings. This section discusses several important reforms that could help achieve this sensible goal.

First, equalizing the rates would mean eliminating the 10 percent of specified tangible assets factor in the FDII and GILTI computations.[xxix] This feature of the new law creates a clear and harmful incentive for companies to move real jobs and operations offshore and will likely allow many companies to avoid all taxes on their offshore earnings.

Second, equalizing the rates would mean eliminating the 50 percent deduction on GILTI, meaning that the effective rate would go from 10.5 percent to the full 21 percent rate that is applicable to domestic income. The 10.5 percent effective rate is a powerful motivation to shift profits and real operations from the United States to offshore tax havens, an incentive that loses substantial revenue and encourages significant tax avoidance and loss of U.S. jobs. Relatedly, foreign income of oil and gas companies should not be exempt from residual taxation as is allowed under the current GILTI regime.

Third, equalizing the rates would mean eliminating the tax break for FDII. This tax break creates an unjustified windfall for certain types of income and is likely to trigger retaliation from trade partners.

Finally, equalizing the rates would mean applying the foreign tax credit limitation on a per-country, rather than worldwide basis. Such a policy would ensure that companies could no longer blend income tax from low and high tax jurisdictions to artificially lower their U.S. taxation through artificially managing their foreign tax credits, a well-documented loophole that the new law failed to close.

Eliminate Inversions

While the attention paid to inversion transactions has waned, the need to prevent tax-motivated expatriations has not diminished. Despite all of the rhetoric from proponents of the TCJA, there are still significant incentives for companies to invert. In fact, in recent months a U.S. based auto parts supplier announced that it will invert, despite the TCJA and anti-inversion regulations enacted by the Treasury Department.[xxx] In addition, closing down other loopholes could spur more companies to pursue the inversion loophole as a last-gasp strategy to continue their tax avoidance, which makes additional anti-inversion measures a vital complement to these provisions.

The most vital component of an anti-inversion strategy is to tighten the definition of a foreign corporation. Lawmakers should prevent a company from becoming foreign through a merger if it continues to be managed and controlled in the United States or if a majority of the U.S. company’s shareholders own the resulting company.

Building on this, lawmakers should crack down on the incentive to invert by restricting the ability of multinational companies to reduce their taxes through payments to offshore subsidiaries. First, this should include enhancing the BEAT by including cost of goods sold as part of the BEAT base. Second, it should include further restrictions to the deductibility of excess interest payments.

Finally, it is worth noting that the TCJA did include some strong anti-inversion measures, such as making companies pay the full rate rather than a reduced rate on earnings deemed repatriated by the TCJA and including cost of goods sold as part of the BEAT base for inverted companies.[xxxi] Such provisions should remain intact, but with the lower threshold for what constitutes an inverted company.

Create Transparency

Tax haven abuse and international tax avoidance has managed to thrive largely because it has been able to operate outside the view of the public and lawmakers. To truly ensure that our international tax system is fair, companies should be required to come clean about the amount of taxes they pay (and the amount they avoid) by publicly disclosing basic information about their operations on a country-by-country basis.

Before the passage of the TCJA, information on the offshore tax approaches of multinational corporations was shrouded in secrecy, with only scant information on which to gauge how companies are shifting profits offshore. One of the only proxies for gauging the scale of offshore tax avoidance was the disclosure by companies in their annual reports of the amount of “permanently reinvested earnings” or untaxed offshore earnings they maintain.[xxxii] With the end of the deferral system companies will no longer have any incentive to maintain these offshore earnings stashes and thus the public, investors, and lawmakers will no longer be able to use this data point as a proxy for measuring offshore tax avoidance. [xxxiii] In other words, following the passage of the TCJA, there will be even less useful data points for gauging the volume of international corporate tax avoidance.

To bring real transparency to the international tax system, Congress should require companies to publicly disclose in financial filings their total revenues, profit, income tax paid, tax cash expense, stated capital, accumulated earnings, number of full-time employees, and book value of tangible assets on a country-by-country basis. This requirement should not present any additional cost to many companies who are already required to disclose this information to the IRS.[xxxiv]

If Congress does not act, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)[xxxv] or the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)[xxxvi] should act to require country-by-country reporting by major corporations. Both organizations have an obligation to the public and investors to require companies to disclose this crucial information.

Do Not Harm

As part of an effort to reduce the long-term cost of the TCJA, the effective tax rate on GILTI is increased, the BEAT rate is increased, and the FDII tax break is made less generous starting in 2026. While inadequate, these changes would still move the international tax system toward one that raises more revenue and less of incentive to shift profits and jobs offshore. It is likely that multinational corporations and their supporters will attempt to prevent these higher rates from going into effect by either delaying them or making the lower rates permanent, but these efforts would represent a step back from tax reform and should be rejected.

Existing Legislative Proposals

Lawmakers have been moving quickly to introduce legislation to fix problems created by the new international tax system. Several bills would make significant progress in achieving the various broad policy changes discussed above.

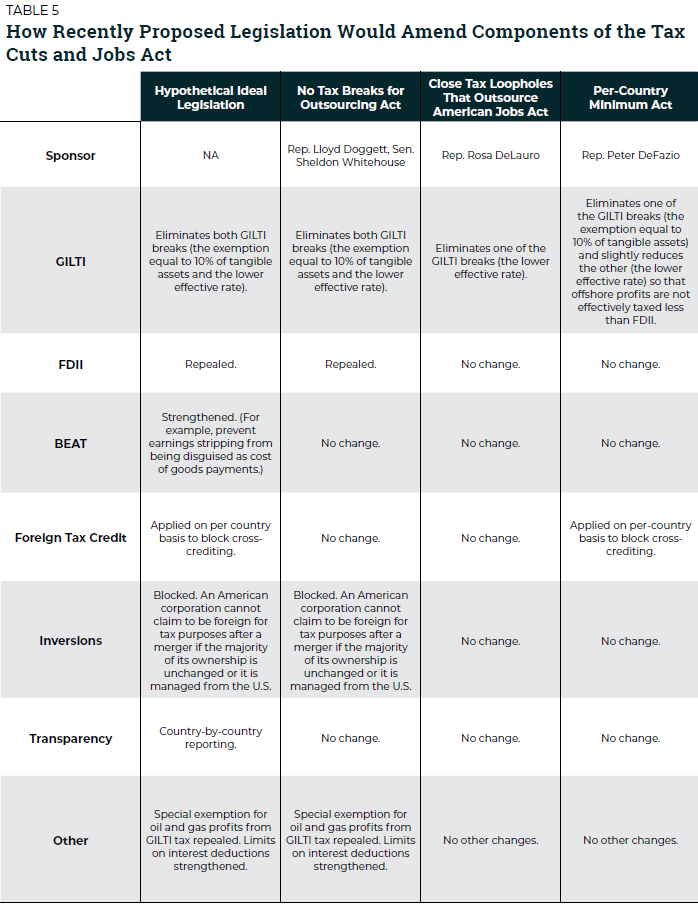

The most comprehensive legislation released to end offshore tax avoidance is the No Tax Breaks for Outsourcing Act, originally introduced in the House of Representatives[xxxvii] by the ranking member of the Tax Policy Subcommittee of the Ways and Means Committee Rep. Lloyd Doggett and originally introduced in the Senate[xxxviii] by Senate Finance Committee Member Sheldon Whitehouse. The bill would eliminate the specified tangible assets factor, eliminate the 50 percent deduction for GILTI, eliminate the exemption of foreign oil and gas income from taxation, eliminate the deduction on FDII, tighten the definition of a foreign corporation, and restrict the deductibility of excess interest payment. This bill would go a long way to shutting down offshore tax avoidance and restoring fairness to the tax system.[xxxix]

The Close Tax Loopholes That Outsource American Jobs Act, introduced by Rep. Rosa DeLauro, takes a narrower approach.[xl] This legislation would eliminate the deduction on GILTI income (thus increasing the rate on GILTI to 21 percent), but leave the rest of the international provision intact.

The Per-Country Minimum Act introduced by Ranking Member of the Transportation Committee Rep. Peter DeFazio, would serve to reshape the current GILTI taxation regime into a higher and more effective minimum tax.[xli] It would accomplish this by applying the tax on GILTI on a per-country basis, rather than a worldwide consolidated basis, as is done under the current system and under the Doggett-Whitehouse bill. In addition, the bill would eliminate the specified tangible assets factor and match the deduction on GILTI to the deduction on FDII, meaning that companies would pay an effective rate of 13.125 percent, rather than 10.5 percent. This bill would reduce the incentive to shift real operations offshore, prevent companies from avoiding taxes by blending their tax rates from high- and low-tax jurisdictions, and raise the minimum tax rate on foreign earnings.[xlii]

While no new legislation requiring country-by-country reporting has been introduced following the passage of the TCJA, two pieces of legislation were introduced in 2017 that would require full public disclosure of important financial information. The Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act, another bill originally sponsored by Sen. Whitehouse and Rep. Doggett, includes country-by-country disclosure as one of its many provisions aimed at stopping tax avoidance under the previous international tax regime.[xliii] In addition, Rep. Mark Pocan introduced the Tax Fairness and Transparency Act, which would require full public country-by-country disclosure in addition to moving the old international system to a full worldwide tax system.[xliv]

As lawmakers look to reform the international tax code, they should use the broad tax policy goals and legislation outlined above as a starting point for achieving an international tax code free of offshore tax gaming. Lawmakers should not wait to finally get the U.S. international tax system in order.

[i] “Chairman Brady Opening Statement at Hearing on How Tax Reform Will Grow Our Economy and Create Jobs.,” MAY 18, 2017. https://waysandmeans.house.gov/chairman-brady-opening-statement-hearing-tax-reform-will-grow-economy-create-jobs/; GOP, “Trump’s Tax Reform Will Help End Offshore Tax Loopholes & Create Jobs,” October 25, 2017. https://gop.com/trumps-tax-reform-will-help-end-offshore-tax-loopholes-create-jobs-rsr; U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “Comment Letter on Tax Reform to Chairman Hatch,” July 11, 2017. https://www.uschamber.com/letter/comment-letter-tax-reform-chairman-hatch; Americans for Prosperity, “Tax Reform: Restoring Economic Growth through Neutrality and Simplicity,” April 12, 2013 http://waysandmeans.house.gov/UploadedFiles/Americans_for_Prosperity.pdf

[ii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “The 35 Percent Corporate Tax Myth,” March 9, 2017. https://itep.org/the-35-percent-corporate-tax-myth/

[iii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Trump Tax Cuts Likely Make U.S. Corporate Tax Level Lowest Among Developed Countries,” April 11, 2018. https://itep.org/trump-tax-cuts-likely-make-u-s-corporate-tax-level-lowest-among-developed-countries/

[iv] Edward D. Kleinbard, “‘Competitiveness’ Has Nothing to Do With It,” September 10, 2014. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2476453

[v] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and U.S. PIRG, “Offshore Shell Games 2017,” October 17, 2017. https://itep.org/offshoreshellgames2017/

[vi] Kimberly A. Clausing, “Profit shifting and U.S. corporate tax policy reform,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, May 10, 2016. https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/profit-shifting-and-u-s-corporate-tax-policy-reform/

[vii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “What Real Tax Reform Should Look Like,” April 27, 2017. https://itep.org/what-real-tax-reform-should-look-like/

[viii] This calculation does not incorporate the provision to impose a one-time tax, at reduced rates, on the profits that American corporations are officially holding offshore. This proposal, which is sometimes called a “deemed repatriation,” raises revenue during the official 10-year budget window and is technically a tax increase. But this provision is a significant break to many, if not most, American multinational corporations and the revenue raised would be temporary. As another ITEP report explains, this provision would, in the long-run, reduce taxes for American multinational corporations by hundreds of billions of dollars.; Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Multinational Corporations Would Receive $413 Billion in Tax Breaks from Congressional Repatriation Proposal,” December 16, 2017. https://itep.org/multinational-corporations-would-receive-over-half-a-trillion-in-tax-breaks-from-the-house-repatriation-proposal/

[ix] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act”,” December 18, 2017. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053

[x] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028,” April 9, 2018. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

[xi] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Turning Loopholes into Black Holes: Trump’s Territorial Tax Proposal Would Increase Corporate Tax Avoidance,” September 6, 2017. https://itep.org/turning-loopholes-into-black-holes-trumps-territorial-tax-proposal-would-increase-corporate-tax-avoidance/

[xii] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act”,” December 18, 2017. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053

[xiii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and U.S. PIRG, “Offshore Shell Games 2017,” October 17, 2017. https://itep.org/offshoreshellgames2017/

[xiv] David Cay Johnston, “Apple’s Sweetheart Tax Deal,” DC Report, January 26, 2018. https://www.dcreport.org/2018/01/26/apples-sweetheart-tax-deal/

[xv] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act”,” December 18, 2017. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053

[xvi] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Multinational Corporations Would Receive $413 Billion in Tax Breaks from Congressional Repatriation Proposal,” December 16, 2017. https://itep.org/multinational-corporations-would-receive-over-half-a-trillion-in-tax-breaks-from-the-house-repatriation-proposal/

[xvii] In a significant giveaway to multinational extractive companies, foreign oil and gas income is exempted entirely from taxation under the GILTI regime.

[xviii] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028,” April 9, 2018. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

[xix] Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 9, 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-tax-law-is-fundamentally-flawed-and-will-require-basic-restructuring

[xx] Rebecca M. Kysar, “JUDGING THE NEW INTERNATIONAL TAX REGIME: Testimony of Rebecca M. Kysar Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance,” April 24, 2018. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/24APR2018KysarSTMNT.pdf

[xxi] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act”,” December 18, 2017. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053

[xxii] Rebecca M. Kysar, “JUDGING THE NEW INTERNATIONAL TAX REGIME: Testimony of Rebecca M. Kysar Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance,” April 24, 2018. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/24APR2018KysarSTMNT.pdf

[xxiii] Rebecca M. Kysar, “The Senate Tax Plan Has a WTO Problem,” November 12, 2017. https://medium.com/whatever-source-derived/the-senate-tax-plan-has-a-wto-problem-guest-post-by-rebecca-kysar-31deee86eb99

[xxiv] Robert Sledz, “European Commission Says U.S. BEAT and FDII Rules May Violate Int’l Standards,” Thomson Reuters, March 27, 2018. https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/blog/european-commission-says-u-s-beat-and-fdii-rules-may-violate-intl-standards/

[xxv] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act”,” December 18, 2017. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053

[xxvi] Rebecca M. Kysar, “JUDGING THE NEW INTERNATIONAL TAX REGIME: Testimony of Rebecca M. Kysar Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance,” April 24, 2018. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/24APR2018KysarSTMNT.pdf

[xxvii] Kamin, David and Gamage, David and Glogower, Ari D. and Kysar, Rebecca M. and Shanske, Darien and Avi-Yonah, Reuven S. and Batchelder, Lily L. and Fleming, J. Clifton and Hemel, Daniel Jacob and Kane, Mitchell and Miller, David S. and Shaviro, Daniel and Viswanathan, Manoj, “The Games They Will Play: Tax Games, Roadblocks, and Glitches Under the 2017 Tax Legislation,” December 18, 2017. Minnesota Law Review, Forthcoming. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3089423

[xxviii] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act”,” December 18, 2017. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053

[xxix] An interim step to full elimination could be to lower the deduction rate to below 10 percent and set it equal to a more reasonable measure of a normal return on investment, such as the 10-year Treasury bond interest rate.; Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, “New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 9, 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/new-tax-law-is-fundamentally-flawed-and-will-require-basic-restructuring

[xxx] Chester Dawson and Theo Francis, “Despite U.S. Tax Overhaul, Ohio-Based Dana Considers a Move Abroad,” Wall Street Journal, March 9, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/dana-to-take-over-gkns-automotive-driveline-business-1520614366

[xxxi] Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “Issues in International Corporate Taxation: The 2017 Revision,” Congressional Research Service, May 1, 2018. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45186.pdf

[xxxii] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and U.S. PIRG, “Offshore Shell Games 2017,” October 17, 2017. https://itep.org/offshoreshellgames2017/

[xxxiii] Gary Kalman and Clark Gascoigne, “Comments on the Exposure Draft for the Proposed Accounting Standards Update to Income Taxes (Topic 740),” FACT Coalition, May 3, 2018. https://thefactcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/FACT-FASB-CbCR-Letter-20180503-Final.pdf

[xxxiv] FACT Coalition, “FACT Sheet: Public Country-by-Country Reporting,” September 27, 2017. https://thefactcoalition.org/fact-sheet-public-country-country-reporting

[xxxv] Robert S. McIntyre, “Comments to the Securities and Exchange Commission on the Business and Financial Disclosure Required by Regulation S-K,” Citizens for Tax Justice, July 21, 2016. https://www.ctj.org/comments-to-the-securities-and-exchange-commission-on-the-business-and-financial-disclosure-required-by-regulation-s-k/

[xxxvi] Richard Phillips, “Comments on the Exposure Draft for the Proposed Accounting Standards Update to Income Taxes (Topic 740),” September 30, 2016. https://itep.org/comment-letter-to-fasb-on-income-tax-disclosure/

[xxxvii] H.R.5108 – No Tax Breaks for Outsourcing Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5108/

[xxxviii] S.2459 – No Tax Breaks for Outsourcing Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2459

[xxxix] Richard Phillips, “New Legislation Would End Tax Incentives to Move Jobs and Profits Offshore,” Just Taxes Blog, May 24, 2018. https://itep.org/new-legislation-would-end-tax-incentives-to-move-jobs-and-profits-offshore/

[xl] H.R.5145 – Close Tax Loopholes That Outsource American Jobs Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5145

[xli] H.R.6015 – Per-Country Minimum Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6015/

[xlii] Richard Phillips, “New Legislation Would Close Significant Offshore Loopholes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Just Taxes Blog, June 6, 2018. https://itep.org/new-legislation-would-close-significant-offshore-loopholes-in-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/

[xliii] H.R.1932 – Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1932

[xliv] H.R.2057 – Tax Fairness and Transparency Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2057