Download the Executive Summary

Narrow Federal Action Would be Unfair, Arbitrary, and Ineffective

The federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) enacted last year temporarily capped deductions for state and local tax (SALT) payments at $10,000 per year. The cap, which expires at the end of 2025, disproportionately impacts taxpayers in higher-income states and in states and localities more reliant on income or property taxes, as opposed to sales taxes. Increasingly, lawmakers in those states who feel their residents were unfairly targeted by the federal law are debating and enacting tax credits that can help some of their residents circumvent this cap—a policy this report will refer to as “workaround credits.” Specifically, states are offering sizeable tax credits in return for making so-called charitable gifts, rather than ordinary SALT payments, to support public services. This is advantageous to some taxpayers because charitable gifts are treated much more favorably than SALT payments under the new federal tax code.

For taxpayers, using these credits will result in a somewhat higher payment to their state governments (or in some cases, local governments) because the credits only offset part of the cost of donating. In New York, for instance, 85 percent of the donation is returned to the donor with tax credits. But for high-income taxpayers able to itemize at the federal level, the added benefits of the federal charitable deduction will often be large enough to both offset that higher state payment and return a net financial benefit to the taxpayer. Notably, most of the high-income taxpayers likely to benefit from these credits already received significant federal tax cuts under the TCJA.

One unusual result of this arrangement is that for state governments, the “tax cut” associated with the credits will produce an overall revenue gain because the donations expected to flow into state coffers will be larger than the credits flowing out (as noted above, every dollar received by New York’s government only triggers 85 cents of state tax credit payouts). More fundamentally, these credits shift state funding streams away from partly deductible tax payments and toward fully deductible payments that the federal government considers to be charitable gifts. The magnitude of this shift remains to be seen, however, as it will depend on how many taxpayers choose to take advantage of these credits.

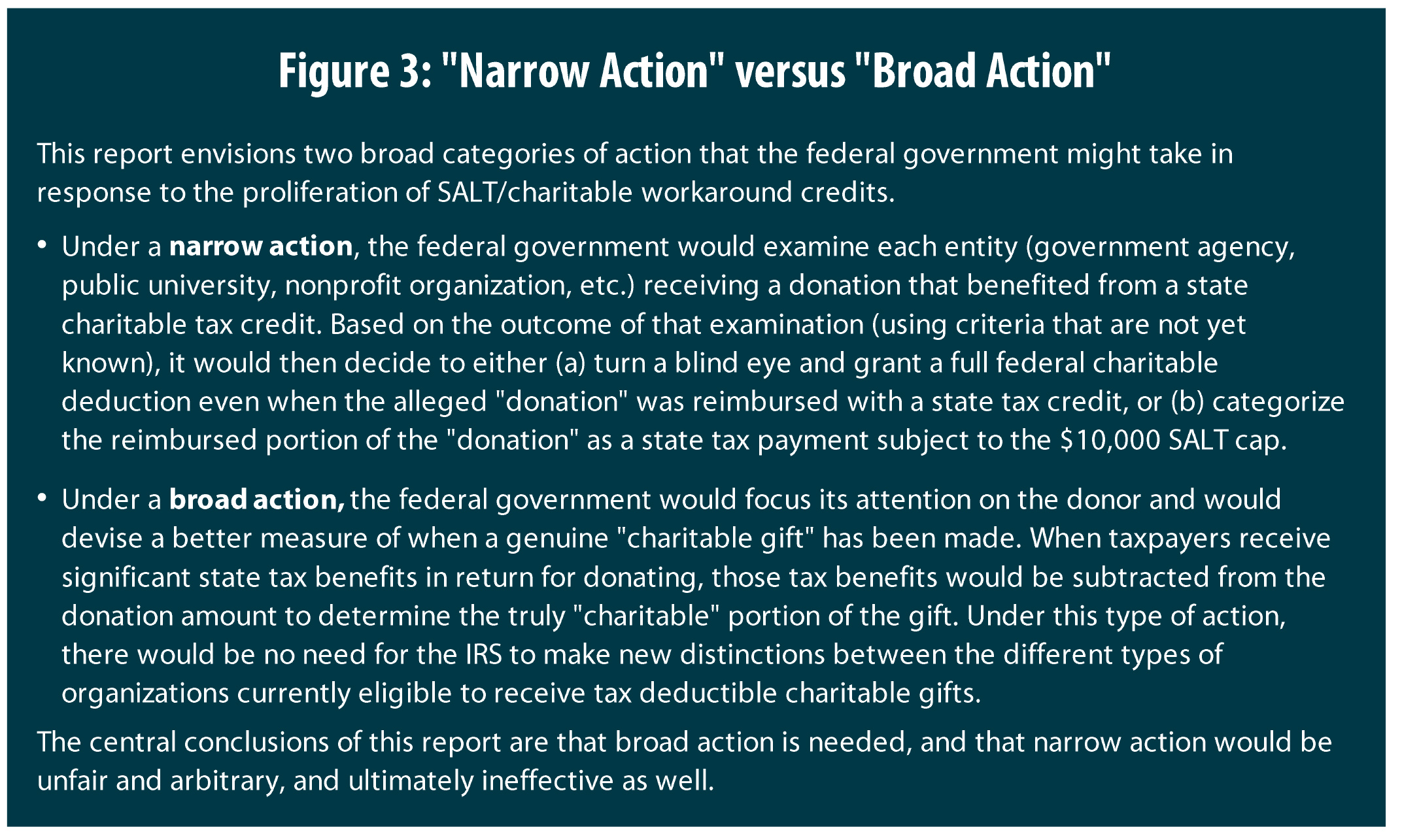

Now that a critical mass of states has adopted these credits (including New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Oregon as of this writing), the focus of the debate will shift toward the federal level and whether the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Treasury Department, and/or Congress will allow these workaround credits to proceed as state lawmakers have planned. This report makes the following findings about potential federal responses to these new workaround credits, and to state charitable tax credits more broadly:

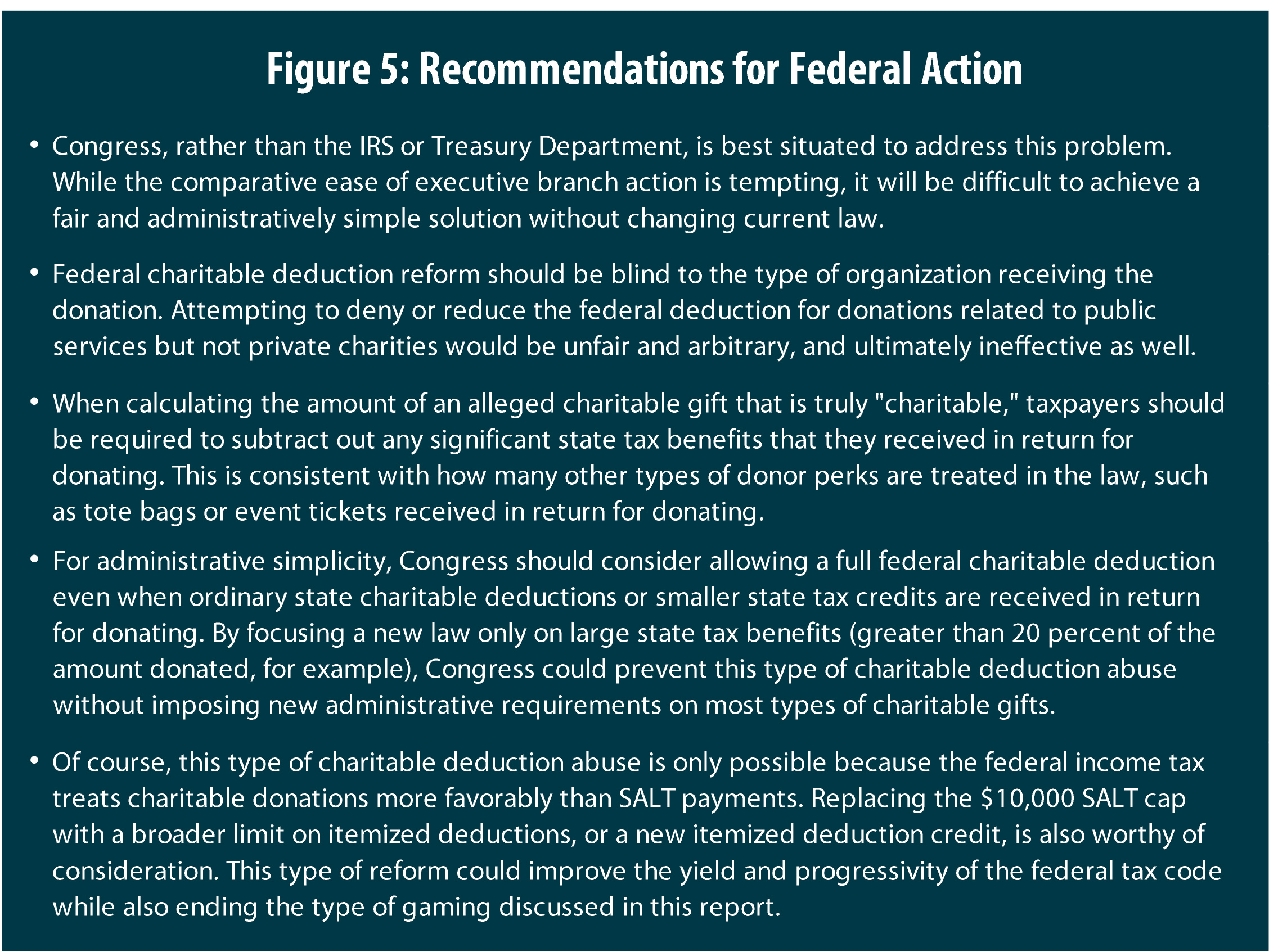

- During last year’s rushed debate over the TCJA, Congress was informed that states and localities were likely to respond to the SALT cap with these types of tax credit schemes, but it ultimately did nothing to prevent them. Much of the debate around this topic has now shifted to whether the IRS has the authority to clean up the mess that Congress left behind, or whether legislation will be needed to address this issue.

- Many observers have responded to these workaround credits with skepticism and shock, and understandably so. The gifts being made under these schemes are not truly “charitable” according to any commonsense definition of that word, since the taxpayers are made financially better off by their gifts.

- But fixing this problem will be more difficult than many observers have recognized, as it runs much deeper than these new workaround credits. While these workaround credits have attracted significant attention in recent months, this type of abuse of the charitable giving deduction has been occurring for many years. Taxpayers have long claimed federal charitable deductions on so-called “charitable gifts” for which the taxpayer received a reimbursement from their state government via a tax credit.

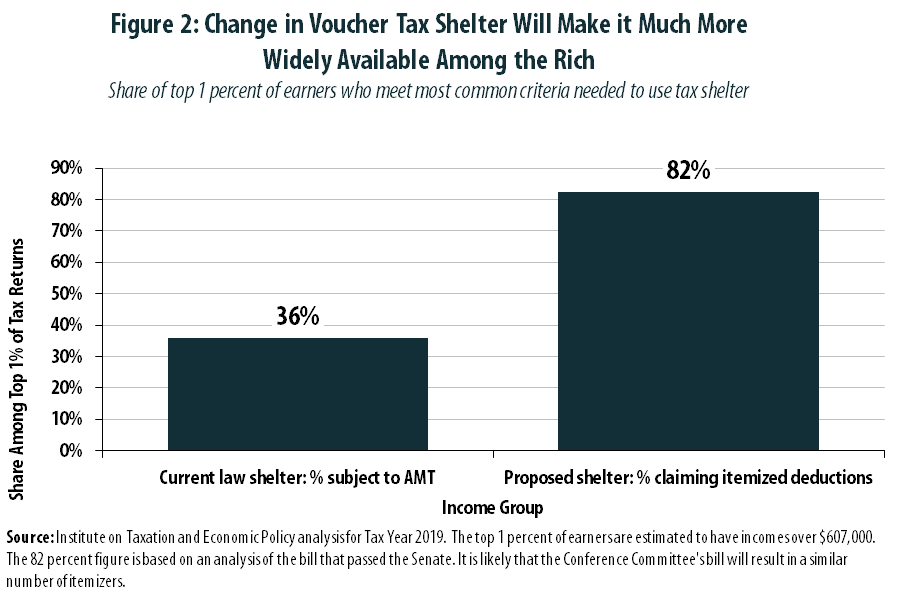

- The closest parallel to these workaround credits in existing tax law is a policy typically favored by conservatives: tax credits that steer funding to private K-12 school vouchers. Tax accountants, private schools, and others in states with such credits have long marketed these programs as tools for exploiting the federal charitable deduction, and in the wake of the new federal tax law they are now using language that mirrors that used by proponents of the new workaround credits. While blue-state efforts to circumvent the SALT cap have attracted more attention, financial advisors in deep-red Alabama and elsewhere are touting the ability of their existing charitable tax credits to help their residents “avoid losing” their SALT deductions. And the sales pitch has proven persuasive. Alabama’s entire allotment of private school tax credits was claimed more quickly this year than ever before.

- Some observers have suggested that the IRS or Treasury Department could intervene with narrowly targeted guidance or a regulation affecting these new workaround credits, but not other pre-existing state charitable credits. This approach would be highly problematic because the new workaround credits have much more in common with existing charitable tax credits than is commonly understood.

- Narrow federal action would be unfair because it would treat similarly situated taxpayers differently depending on the types of causes to which they donate. For example, narrow federal action would likely involve denying tax-credit-reimbursed deductions on donations to public schools, but not private schools, even if the impact of those two types of donations on taxpayers and state coffers was identical.

- Narrow federal action would require making arbitrary distinctions between different types of organizations receiving donations. Existing state charitable tax credits steer donations to a wide range of entities, including government agencies, public institutions, other levels of government, public-private partnerships, and private nonprofits providing services very similar to what a state government might otherwise provide. There is no way to draw a defensible line between the various types of organizations within this broad spectrum.

- Narrow federal action would be ineffective because limiting the federal charitable deduction only for gifts to certain types of organizations would inevitably cause state and local leaders to become more creative in their tax credit designs, tweaking them so that they fall just outside of whatever restrictions the federal government might create. For example, states could replace much of their direct aid to public universities or local governments with tax credit schemes that steer donations to those entities. Or if even those schemes were shut down (a policy change that would affect not just the new workaround credits, but many pre-existing credits as well), states could devise sophisticated programs routing donations through private nonprofits.

- A better approach would address not just the new breed of workaround credits, but other state charitable tax credit schemes as well. Rather than denying the federal charitable deduction for donations to some entities but not others, this approach would focus on the real economic impact of so-called “charitable gifts” from the perspective of the donor, and would reserve the deduction only for gifts that involve a genuine financial sacrifice. This approach would be simpler, fairer, and more effective.

- While the IRS or Treasury Department may have the authority to take some action on this issue with new guidance or a regulation, Congress is far better suited to resolve this in a fair and administratively simple fashion. There appears to be no basis in existing law for reducing the federal charitable deduction when some types of tax benefits are received (e.g., large state tax credits, including the new workaround credits) but not others (e.g., small state tax credits, state tax deductions, or even the federal deduction itself). This makes IRS or Treasury action an all-or-nothing proposition: either all types of tax benefits impact the size of the federal charitable deduction (an administratively complex outcome) or none of them do (that is, the problem remains unresolved). Congress, of course, faces no such limitations in rewriting the charitable deduction laws. It could either craft a more tailored law reducing the deduction when large state tax credits are received, or it could revisit its decision to cap the SALT deduction. If the SALT cap were replaced with a broader reform that did not preference charitable giving over SALT payments, the benefits of attempting to recast tax payments as charitable gifts would be eliminated entirely.

The federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) enacted last year temporarily capped deductions for state and local tax (SALT) payments at $10,000 per year, through 2025. Prior to the bill’s enactment, numerous tax experts warned Congress that the bill was “riddled with problems” and that the SALT cap could be circumvented by state and local lawmakers using a variety of techniques.[1] Congress chose to ignore those warnings, and in the months following the bill’s enactment state and local lawmakers responded as predicted. A growing number of states have implemented tax credit schemes that allow their residents to pay much less in (partly- or non-deductible) state and local tax if they make (deductible) charitable gifts to the same types of public institutions or public services that their taxes might have otherwise funded. As of this writing New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Oregon have enacted workaround credits while other states such as California, Illinois, and Rhode Island continue to debate similar proposals.

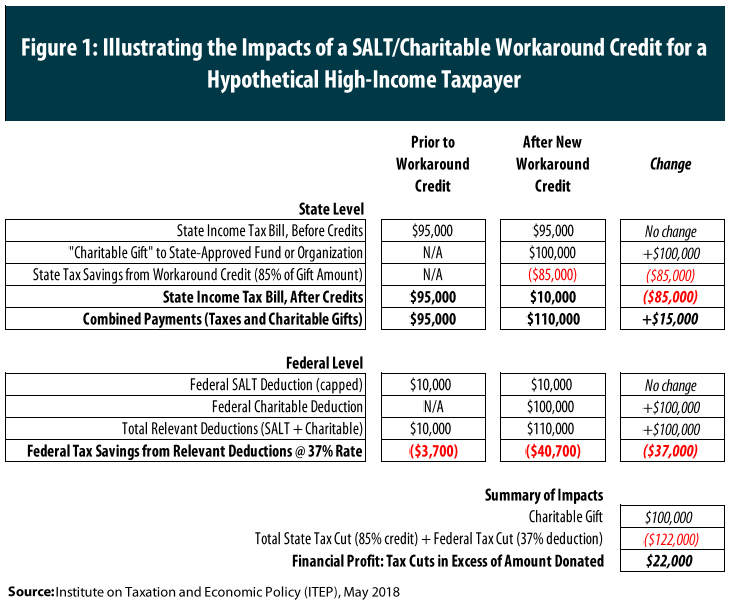

In New York, for instance, a new law allows taxpayers donating to state funds supporting education or health care to receive up to 85 percent of their donation back from the state via a tax credit. Assuming that donation is fully deductible at the federal level, New York taxpayers will also receive a federal deduction worth up to 37 percent of the amount donated.[2] Summing these two breaks (85 and 37 percent) yields tax cuts of up to 122 percent of the amount donated—meaning that the taxpayer comes out ahead by making the gift.

Many observers have responded to these tax credits with disbelief, using words like “silly” and “ridiculous.”[3] And rightfully so. It is illogical for a taxpayer to receive a charitable deduction in return for doing something that satisfies nobody’s common-sense definition of charity. The hypothetical taxpayer described in Figure 1, for example, is $22,000 richer after donating than before. This is a far cry from genuine philanthropy.

Some observers have suggested that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) or the Treasury Department can, and should, intervene to shut down these tax credit schemes in the wake of Congress’s failure to address them in the TCJA. But this will be more difficult than is commonly understood, as this general type of scheme is neither new nor unique. The federal government has allowed similar abuses of the charitable deduction to persist for many years, and as this report will show, it is impossible to shut down these new tax credit schemes in a fair and effective manner without also impacting a wide range of existing state tax credits. Put another way, a partial fix aimed just at stopping the most recent flurry of state tax credits would be highly problematic. These new tax credits have much in common with existing state tax policies, and their proliferation should spur Congress, or perhaps the IRS or Treasury Department, to take a long-overdue look at this broad issue, not a narrow one focused only on the newest types of credits.

WHAT ARE THESE NEW WORKAROUND CREDITS?

This report uses the term “workaround credits” as a shorthand for a broad group of state charitable tax credits that have been debated or enacted this year because of the new cap on the SALT deduction. As this report will show, this categorization is made difficult by the fact that the new credits are often not much different from existing state charitable tax credits.

New York’s workaround credits have received the bulk of the attention thus far and offer a useful illustration of the variety of approaches available to states and localities. [4] The New York law allows taxpayers to donate to a new state fund with separate accounts for education and health care expenditures, and to receive an 85 percent tax credit in return. Alternatively, taxpayers can now receive an 85 percent credit for donating to private nonprofits supporting either the State University of New York (SUNY) or the City University of New York (CUNY)—a policy that bears close resemblance to an existing tax credit program in Indiana.[5] Finally, the law also gives localities the option to create property tax credits worth up to 95 percent of the amount donated to new funds called Charitable Gift Reserve Funds.

The local tax credit approach is similar to one enacted by New Jersey lawmakers this year, which allows localities to establish “charitable funds for specific public purposes” that “shall be kept separate from the other accounts of the local unit,” and to distribute tax credits in return for such donations.[6]

Connecticut enacted a variation on the local tax credit option that will allow localities to offer credits of up to 85 percent of the amount donated to nonprofit “community supporting organizations” that are “organized solely to support municipal expenditures for public programs and services, including public education.”[7]

And Oregon also enacted a program this year that, while less widely reported in the media, was described as a SALT cap workaround by its author, State Sen. Mark Hass.[8] The new law allows for large tax credits to be paid out in return for donations to the state’s Opportunity Grant Fund, which is used by the state’s Higher Education Coordinating Commission to provide financial aid to help students attend college. [9] This credit is very similar to an existing California credit that funds student financial aid.[10]

As of this writing, states such as California, Illinois, and Rhode Island are continuing to debate new tax credits that could fit the definition of “workaround credits.”

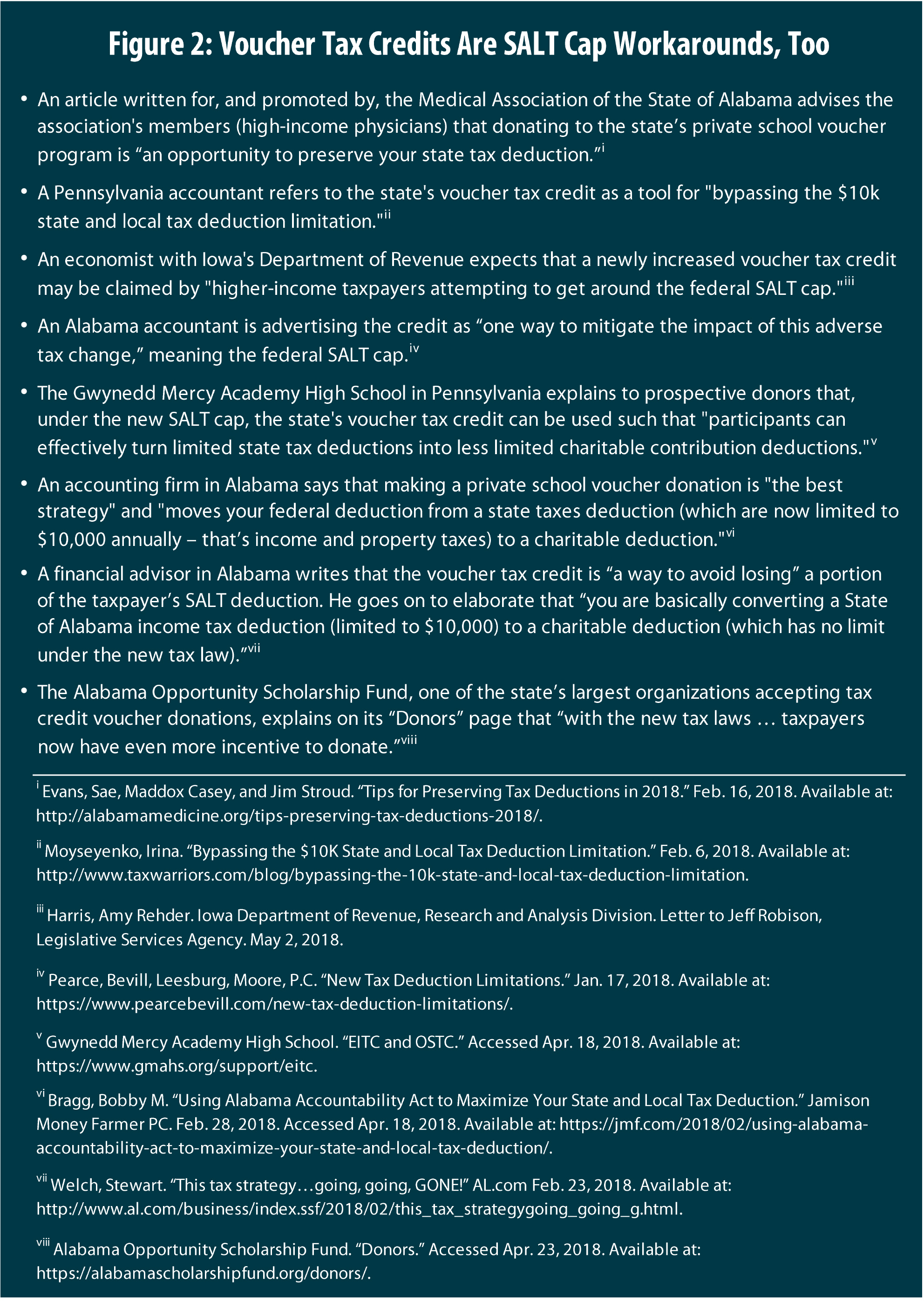

But these new credits are not the only ones being marketed to taxpayers as SALT cap workarounds. Alabama, for instance, has offered its taxpayers a 100 percent tax credit since 2013 in return for donations to organizations that provide vouchers to families that send their children to private K-12 schools. And Pennsylvania has offered a variety of similar credits since 2001 worth 75, 90, or 100 percent of the amount donated.[11]

In both states, tax accountants, financial advisors, and the organizations benefiting from these credits have been eager to point out to potential donors that the credits can be used to get around the new federal cap on SALT deductions. A sampling of statements along these lines is available in Figure 2.

Some observers have suggested that in deciding which types of state tax credits will be subject to stricter federal rules, state lawmakers’ intent may be factored into the IRS’s decision making.[12] But once the law is enacted, lawmakers’ original intent matters much less than the manner in which the credit is presented to potential claimants and the ways in which it is used.

The types of statements presented in Figure 2 are not merely idle chatter. In Alabama, a surge of interest among taxpayers seeking to circumvent the SALT cap led to the state’s entire allotment of tax credits ($30 million) being claimed more quickly this year than at any time in the program’s history.[13] ITEP predicted this would happen in a report issued last December.[14] And accountants in the state anticipated a similar outcome with disclaimers like: “beware: credits will not last” and “act quickly … before the opportunity is gone.”[15] It turns out that high-income taxpayers living in states such as Alabama and Pennsylvania are already enjoying the personal financial benefits of SALT cap workarounds, while those living in California, New York, and elsewhere are still waiting for their lawmakers to finish debating or implementing workaround credits.

NARROW ACTION AGAINST WORKAROUND CREDITS WOULD BE UNFAIR, VIOLATING TAX PRINCIPLE OF HORIZONTAL EQUITY

The most objectionable feature of these new workaround credits is a familiar one: taxpayers will receive federal charitable deductions for behavior that meets almost nobody’s commonsense definition of philanthropy. If a taxpayer makes a so-called “donation” only to later be reimbursed (in full or in part) by their state government with tax credits, then the part of the donation that was reimbursed is clearly not charitable because it involved no financial sacrifice.

This concept is already well established in the context of other types of reimbursements. A donor who receives a tote bag or a steak dinner, for example, in return for donating must reduce their federal charitable deduction by the value of the item or service they received. This is consistent with the original intent of the charitable deduction to encourage genuine charitable giving rather than self-interested tax avoidance, a fact reiterated by more recent reforms to the deduction’s treatment of donations of property that has grown in value.[16]

But federal tax law is blind to reimbursements that come in the form of state tax credits, even if those credits are so large that they wipe out of the cost of “donating” entirely.

Rather than broadly improving the federal tax code’s measurement of real philanthropy by requiring taxpayers to reduce their deductions by the amount of state tax credits they receive in return, the narrow type of federal action being considered would allow some pseudo-donors to continue receiving full deductions while denying or reducing those deductions for others. This distinction would not be based on the taxpayers’ actual level of financial sacrifice, but rather on the type of organization that accepts the donation.[17]

Under a narrow federal approach, a donation to a fund supporting public schools, for instance, would likely not be deductible if it was reimbursed with a tax credit. An identically-reimbursed donation to an organization supporting private schools, however, would remain deductible. In effect, pseudo-donations flowing to public institutions would be categorized as tax payments subject to the new SALT cap, while pseudo-donations supporting private ones would continue to be treated as genuine, fully deductible charitable gifts.

This type of distinction would amount to a clear violation of the tax fairness concept of “horizontal equity,” under which similar taxpayers should be treated similarly by the tax code.

In the real world, this would mean that a New York taxpayer making a pseudo-donation to support public education would lose most of their federal charitable deduction if they claimed the state’s 85 percent tax credit for such donations. An Alabama taxpayer making an even-less-charitable donation to support private school vouchers, by contrast, would continue to receive their full federal deduction even if they claimed a 100 percent tax credit from their state in return for making such a gift. As explained earlier, both of these tax credits are being marketed to taxpayers as ways to circumvent the SALT cap. And indeed, the Alabama credit is actually the more lucrative option in this regard, since it reimburses 100 percent of the amount donated rather than only 85 percent. But nonetheless, the narrow federal approach would deny the New Yorker’s charitable deduction while leaving the Alabamian’s deduction intact.

Some observers have tried to defend this inconsistency by suggesting that the IRS may only limit or deny deductibility for donations that support services that would have been funded even if the donation was not made.[18] According to this line of reasoning, these types of donations are most akin to tax payments and should be subject to the SALT deduction cap. But implementing this test would require proving a counterfactual and is therefore impractical. How is the IRS to know, for example, whether Alabama would have funded a $30 million private school voucher program through a direct appropriation in the absence of its $30 million voucher tax credit program? There is little logic in capping a taxpayer’s SALT deductions for state income tax payments that are used to fund a private school voucher program, but allowing that same taxpayer an uncapped charitable deduction for state-reimbursed “donations” funding a nearly identical program. The result of both arrangements on taxpayers, state coffers, and funding for school vouchers is the same.

The heart of this problem is an abuse of the charitable giving deduction, whereby pseudo-donors who have given up little or nothing of value are nonetheless able to enjoy a federal income tax break. As ITEP showed last year in a report co-authored with AASA, the School Superintendents Association, voucher tax credits are routinely marketed as tools for generating federal charitable deductions without having to make genuine charitable donations.[19] Private schools and financial advisors commonly use phrases like “make money” and “profit” when describing the lucrative state and federal tax cuts generated by a pseudo-donation.

The heart of this problem is an abuse of the charitable giving deduction, whereby pseudo-donors who have given up little or nothing of value are nonetheless able to enjoy a federal income tax break. As ITEP showed last year in a report co-authored with AASA, the School Superintendents Association, voucher tax credits are routinely marketed as tools for generating federal charitable deductions without having to make genuine charitable donations.[19] Private schools and financial advisors commonly use phrases like “make money” and “profit” when describing the lucrative state and federal tax cuts generated by a pseudo-donation.

Donors who choose to act on this type of advice often do not care where their money is going. For evidence of this, look no further than Alabama which has fully reimbursed pseudo-donations with 100 percent tax credits for several years, and yet has still often struggled to generate enough interest in its private school voucher program to reach its full $30 million allotment. Anybody in Alabama with a real interest in supporting private school vouchers would have been donating to this program already, as the state’s 100 percent credit made those donations costless to the taxpayer. It was not until the donations actually became profitable for a larger group of taxpayers—because of the SALT cap—that the state began easily distributing its full credit allotment. It would be inappropriate for the federal government to treat New York “donors” supporting public education less favorably than Alabama “donors” supporting private schools, when both groups’ behavior shows the same lack of charitable intent or effect.

In fact, it is not even necessary to compare different states for the inequities of a narrow federal approach to become apparent. Arizona, for instance, offers significant tax credits for donating to support private school vouchers, as well as a smaller credit for donating to support public schools.[20] Under the narrow approach, Arizonans seeking to make smart financial decisions for their families would continue to see profit potential in donating to support private school vouchers, but would lose the ability to turn an even smaller profit from donating to support public schools.

NARROW ACTION WOULD REQUIRE ARBITRARY CUTOFFS

Some observers have suggested that these workaround credits are somehow unique, and that the IRS, Treasury, or Congress could take narrow action against them without impacting the deductibility of gifts benefiting from many pre-existing state charitable tax credits. This argument seems to hinge on the idea that credits for donating to public services that would have been funded with taxes anyway can be neatly distinguished from credits for donating to private institutions. But the reality is that these new workaround credits are extremely similar to many existing tax credits.

Earlier this year, a team of academics working on this topic identified more than one hundred state charitable tax credits across 33 states.[21] Many of those credits are offered in return for donating to government agencies, public institutions, or regulated nonprofits performing services of the same type that states often provide directly.[22] The types of entities benefiting from these credits vary widely in their level of connection to governments, and it is impossible to draw a reasonable, definitive line between tax credits supporting public services and those only benefiting private institutions.

The below discussion offers an overview of some of the types of entities to which states seek to encourage donations by offering charitable tax credits. This is not a comprehensive accounting of these types of state policies.

- Credits for donating to governmental funds. This is the most common type of tax credit structure being pursued in the wake of the new federal tax law. Earlier this year New York lawmakers created the New York Charitable Gifts Trust Fund, with separate accounts for health and for education.[23] In the same bill, lawmakers also gave localities the ability to create Charitable Gift Reserve Funds to accept donations. Meanwhile in New Jersey, localities can now establish “charitable funds for specific public purposes” that “shall be kept separate from the other accounts of the local unit.”[24] Other states continue to debate similar funds. Illinois lawmakers, for instance, are considering creating the Illinois Excellence Fund, which is a special fund subject to appropriation by the legislature exclusively for public education purposes.[25] California lawmakers are debating a new California Excellence Fund, which would be housed in the state general fund but would give donors some control over how their donations would be spent, including on K-12 education, higher education, or state parks. Rhode Island lawmakers are contemplating a new Rhode Island Ocean State Fund, housed in the state’s general fund and under the control of the legislature.[26] And District of Columbia lawmakers have proposed creating the District of Columbia Public Education Investment Fund, administered by the District’s Chief Financial Officer.[27] The money in the fund must be used for public education and cannot be transferred into the general fund.

- Credits for donating to specific government agencies. These types of tax credits have a longer history at the state level, though Oregon lawmakers opted to implement this type of credit this year as a response to the SALT cap. Specifically, Oregon has created a new tax credit designed to reward donations to the Opportunity Grant Fund, from which funds are continuously appropriated to the Higher Education Coordinating Commission inside the state’s Chief Education Office.[28] This is very similar to a tax credit in California used to provide financial aid to students by encouraging donations to the College Access Tax Credit Fund, administered by the State Treasurer.[29] In Arkansas, the state offers a tax credit for donations to the Public Roads Incentives Fund, managed by the Arkansas Economic Development Commission to be used to aid in the construction of public roads.[30] Georgia offers a tax credit for donations to the Innovation Fund Foundation, which is controlled by the Georgia Governor’s Office of Student Achievement.[31] Louisiana offers a tax credit for donations to Family Responsibility Programs administered by the state’s Department of Health and Hospitals. Separately, the state also offers a tax credit for donations to state-owned playgrounds in economically depressed areas. Missouri offers tax credits for donations to the Missouri Agricultural and Small Business Development Authority, which is housed in the state’s Department of Agriculture.[32] Oregon offers a tax credit for donations to the Child Care Contribution Tax Credit program, managed by the Oregon Department of Education’s Early Learning Division. The donations are described as “supporting a statewide early learning system that is safe, high quality and accessible,” and the funds are distributed to child care businesses throughout Oregon.[33] And finally, many states offer tax credits for donations of land or easements to state agencies for conservation purposes.[34]

- Credits for donating to public institutions. Indiana and Montana offer tax credits for donations to institutions of higher education within the state.[35] This includes public universities that also receive funding from state appropriations. Idaho offers a broader tax credit for donations to elementary and secondary schools, as well as higher education and other organizations.[36] And Louisiana offers a tax credit for technology donated to a very wide variety of schools.[37]

- Credits for donating to other levels of government. Taxpayers in Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Louisiana, and Montana can receive state tax credits for donating to public K-12 schools. These credits are similar to state aid to localities, since state revenues are being diminished for the benefit of local schools. Similar intergovernmental credit programs include Colorado’s tax credit for donations to enterprise zone administrators, many of which are local governments’ economic development offices.[38] And Nebraska offers a credit for donations to community development programs, some of which are administered by local government units.[39]

- Credits for donating to nonprofits with purpose of benefiting public organizations. Indiana allows a tax credit not just for direct donations to colleges and universities, but also to “corporations and foundations organized and operated exclusively for the benefit of any eligible colleges or universities.”[40] This is very similar to a new workaround credit enacted in New York this year, which offers tax credits for donations to two separate 501(c)(3) foundations: one benefiting the State University of New York (SUNY) system and another benefiting the City University of New York (CUNY).[41] Oklahoma offers a tax credit for donations to Educational Improvement Granting Organizations, which provide grants to rural public schools.[42] And Connecticut lawmakers enacted a workaround option for its localities that will allow them to choose to offer tax credits to property tax payers who donate to “community supporting organizations,” which are 501(c)(3) organizations “organized solely to support municipal expenditures for public programs and services, including public education.” [43]

- Credits for donating to public-private partnerships. Missouri offers a tax credit for donations to “Innovation Campuses,” which are partnerships between high schools, higher educational institutions, technical colleges, and/or businesses.[44]

- Credits for donating to nonprofits created and/or managed by the state. Kansas offers a tax credit for donations to Network Kansas, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that was established by the state to “promote an entrepreneurial environment.”[45] Network Kansas often works with the Kansas Department of Commerce, which is listed as a “founding partner.”[46] Oregon offers a tax credit for donations to the Oregon Cultural Trust, a nonprofit created by the state as “an ongoing funding engine for arts and culture across the state.”[47] The Trust works with a number of state agencies. South Carolina offers a tax credit for donations to the Industry Partnership Fund, which is managed by the South Carolina Research Authority, a non-profit organization created by the state.[48] Additionally, South Carolina’s private school voucher tax credit flows through a 501(c)(3) organization created by the state and governed by political appointees and extensive state laws.[49]

- Credits for donating to nonprofits providing services that a state may have provided directly in the nonprofit’s absence. Some skeptics of the new workaround credits have suggested that their downfall may be that they are funding services that the state would have funded even in the absence of the credit.[50] This is a counterfactual that is impossible to prove, and it could apply equally to many existing state charitable credits. For instance, many of the eighteen states providing funding for private K-12 school vouchers via a tax credit program may have provided that funding through a direct appropriation in the absence of the tax credit.[51] Separately, states such as Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Missouri, and Utah fund various social services programs via state tax credits.[52] These include tax credits for donating to organizations that provide foster care, substance abuse counseling, or care for the disabled. Missouri’s tax credit for donating to licensed residential treatment facilities is particularly notable, since it is only available for donations to facilities that “are under contract with the Department of Social Services (DSS) to provide treatment services for children who are residents or wards of residents of … this state.”[53] Missouri also administers a separate program designed to promote positive youth development, but only allows donations to organizations whose detailed proposals for tax credit support receive a high score from the state’s Department of Economic Development.[54] This same design—state tax credit support only for nonprofit organizations with very specific proposals approved by government agencies—is also used in Indiana to steer donations to private nonprofits that help low-income families build wealth.[55]

The multitude and variety of organizations eligible to receive tax-credit-reimbursed donations poses serious problems for any attempt to allow federal charitable deductions for some pseudo-donations but not others. An earlier section of this report already discussed the unfairness of allowing deductions for donations to private schools but not public ones. But the definitional problems could become even more complex than this.

For instance, if the critical distinction is one between donations to “public” versus “private” entities, how would donations of the following types be treated?

- Donations to a private entity that supports public schools, such as Oklahoma’s Educational Improvement Granting Organizations.

- Donations to a publicly operated fund that awards the money to private nonprofits.

- Donations to a heavily regulated nonprofit that is only eligible to receive tax-credit-reimbursed donations if it meets a host of criteria spelled out by legislators or government employees.

A narrow approach that allows federal charitable deductions for some pseudo-donations but not others won’t just be unfair, it will also prove to be arbitrary and confusing. It will inevitably raise difficult questions about why some organizations are exempt from the new rules but not others. In short, it would be a step backward for federal tax policy.

NARROW ACTION WOULD BE INEFFECTIVE

If the IRS, Treasury, or Congress takes narrow action against these workaround credits, they may start by denying charitable giving deductions when tax-credit-reimbursed donations flow to the types of funds discussed at beginning of the previous section: state and local general fund accounts and other similar accounts. This action would have the intended effect of only impacting new workaround credits proposed in the wake of the SALT deduction cap, but it would fall far short of ending these workaround schemes. Some new workaround credits created this year would be unaffected, and lawmakers in states that would be affected by this action would almost surely respond by becoming more creative in their tax credit designs.

For instance, unless federal action also targeted donations to specific government agencies, Oregon’s new workaround credit for donations to the Higher Education Coordinating Commission’s financial aid program would remain unaffected, and more states would undoubtedly seek to fund agency functions with tax-credit-reimbursed donations. On the other hand, if federal lawmakers sought to deny tax deductions for tax-credit-reimbursed donations to government agencies, tax credits in states such as Arkansas, California, Georgia, Louisiana, and Missouri would also be impacted and the scope of the action would no longer be limited to the new workaround credits.

If the federal government decided to deny the charitable deduction on donations to government agencies, the next logical step might be for states to use such tax credits to raise funding for somewhat more independent entities, such as public colleges and universities, that it would otherwise have funded through direct appropriations. This arrangement offers one strategy for getting around some commenters’ suggestions that the IRS should treat charitable tax credits unfavorably if the recipient of the donation (state governments) is the same entity that pays out the benefit to donors (state tax credits). Under this arrangement, colleges and universities would be receiving the donations, but state governments would be providing the tax credits. Of course, the federal government could attempt to stop these types of workaround schemes as well, but not without impacting long-running credits in Idaho, Indiana, Louisiana, and Montana.

States could also attempt to replace a significant portion of their aid to local governments and school districts with a charitable tax credit scheme. Federal action broad enough to prevent this type of workaround would impact a variety of existing state tax credits, including those used for the benefit of public schools in Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Louisiana, and Montana.

Under a narrow federal approach, it would be especially difficult to shut down workaround credits that steer donations to nonprofit organizations rather than governments. In Connecticut, for instance, lawmakers recently granted localities the authority to offer tax credits to fund nonprofits that advance public purposes that the government may otherwise have pursued. In states such as Indiana, New York, and Oklahoma, tax credits are available for donating to nonprofits that exist only to benefit public educational institutions—most often higher education. The New York credits were created as new workarounds this year, while the Indiana and Oklahoma credits have existed for years. In Kansas, a nonprofit created by the state performs an economic development role very similar to state agencies. And nonprofits providing social services in many states also benefit from tax credits. Despite being independent entities, state governments exercise substantial control over the work of these organizations through laws, regulations, and sometimes even requirements that detailed applications must be submitted to the state before those organizations can receive tax-credit-financed funding for particular projects.

Notably, a new workaround credit proposal in California relies heavily on non-profit organizations in its design precisely because this type of credit is less vulnerable to narrow federal action. The proposal from the chair of the California Assembly’s tax-writing committee would allow taxpayers to donate to independent non-profit organizations and receive an 80 percent tax credit in return.[56] The state would recoup its costs, and then some, by requiring nonprofits to acquire those tax credits from the state, at a cost of 90 cents per credit, prior to accepting tax-credit-eligible donations.

The least narrow of the “narrow fix” options would involve the federal government denying or reducing the charitable deduction when tax-credit-reimbursed donations flow not only to state and local governments, but also to nonprofits judged to be significantly entangled with those governments. Under this approach, most of the credits impacted would be existing tax credits rather than the new workaround credits. This approach would allow abuses of the charitable giving deduction to continue when the donations are judged to be flowing to truly independent nonprofits, and it would raise difficult line-drawing questions regarding which nonprofits are sufficiently independent to be exempt from the new federal rules.

One particularly worrisome result of this approach is that it would incentivize democratically elected state and local governments to relinquish control over many of their current functions, even as they still funded those functions via their tax credit programs. If Alabama’s nonprofit “scholarship granting organizations” are judged to be sufficiently independent of the state, for example, high-income taxpayers in Alabama would find that using the state’s 100 percent tax credit program to effectively earmark their tax dollars to private schools would be more financially beneficial than either supporting public schools by paying their state income taxes or using a (hypothetical) workaround tax credit related to public school funding. In effect, conservative-leaning states that are willing to “charitize” large swaths of their public education systems, human services, etc. would be best positioned to grant their taxpayers an opportunity to circumvent the SALT cap. Consider the following examples:

- Scenario 1: Taxpayer pays $50,000 in state income tax that the state uses to fund public schools and other services. Maximum federal deduction is $10,000 because of the SALT deduction cap.

- Scenario 2: Taxpayer “donates” $50,000 to public schools and receives a $50,000 state “workaround credit” in return. In effect, the state has funded this “donation” because the taxpayer’s financial standing is unchanged from Scenario 1 (they have made a $50,000 “donation” rather than paid a $50,000 tax) while the state’s revenues are $50,000 lower. Under a narrow federal fix, the $50,000 “donation” would be categorized as a tax payment for federal tax purposes and the taxpayer’s maximum federal deduction would be $10,000—the same as in Scenario 1.

- Scenario 3: Taxpayer “donates” $50,000 to fund private K-12 school vouchers and receives a $50,000 state tax credit in return. Again, the state has funded this “donation” for the same reasons described in Scenario 2. Under a narrow fix that overlooked nonprofits distributing private school vouchers, this “donation” would be treated as if it were truly charitable and the taxpayer would receive a federal charitable deduction of up to $50,000. In this scenario, the taxpayer’s federal deduction ($50,000) is 5 times larger than in Scenarios 1 or 2 ($10,000) even though the taxpayer’s financial standing is the same, before federal taxes. The relevant difference between this scenario and Scenario 2 is that the state government is paying for children to be educated in private schools, rather than public ones.

This discussion should make clear that any attempt to crack down on some pseudo-donations but not others is sure to raise more questions than it answers. Even proponents of the narrow approach concede that their solutions are not comprehensive answers to this brand of charitable deduction abuse. Andy Grewal at the University of Iowa, for instance, has admitted that “whether the charitable contribution strategy works will depend on the details of a given state’s plans.”[57] And in contemplating some iterations of the charitable credit scheme, Eric Rasmusen of Indiana University conceded that “the amended proposal might be valid, though I am not sure even in my own mind.”[58] Peter Faber of McDermott Will & Emery similarly goes back and forth between discussing state charitable schemes that might work, and those that might not, in his writing on the topic.[59]

As long as some version of the workaround credit scheme is left open for abuse, states, localities, and taxpayers are sure to exploit it to generate federal charitable deductions for acts that are not genuinely charitable. A narrow approach to this issue would be a missed opportunity at real reform and would make the tax code less fair, more arbitrary, and more confusing, without solving the root problem to which these new workaround credits have drawn so much attention.

BROAD ACTION WOULD BE FAIRER, SIMPLER, AND MORE EFFECTIVE

With the creation of new SALT workaround credits, a growing number of taxpayers can now make so-called “charitable donations” that are nothing of the sort because they receive state tax credits and federal tax deductions worth more than their actual donations. Some observers have suggested that the IRS should shut down some of these abuses, but not others, by drawing what would amount to arbitrary distinctions between different tax credit programs based on the nature of the organization receiving the donations. Peter Faber, for instance, has suggested denying the deduction only if the donations fund programs that the state would have funded anyway.[60] As with all counterfactuals, this would be impossible to prove in practice. The result would be unnecessary complexity and an incomplete solution to the problem of charitable deduction abuse.

A much better approach would be for Congress to set its focus squarely on the donors, and to devise a more sophisticated method for determining when an alleged charitable gift is truly charitable, and what portion of each gift is actually charitable. As most commenters on this issue have pointed out, the tax code already requires taxpayers to reduce their charitable deductions by many types of financial benefits they receive in return—such as an NPR tote bag, Super Bowl tickets, or a steak dinner. Extending this same approach to include state tax credits would improve federal tax law.

But while the general notion of denying charitable deductions for reimbursed donations is simple enough, there are a few thorny issues that would need to be overcome to implement this ideal. For this reason, it would be preferable for Congress to take the lead in crafting policy that strikes a careful balance between the need for an improved measurement of genuine charity and the administrative difficulties involved in certain aspects of that measurement.

For example, would taxpayers in the roughly thirty states offering ordinary charitable deductions need to reduce the amount of their federal deduction by the value of the state tax deduction they received?[61] Or how about the value of the federal charitable deduction itself? Would that amount need to be subtracted in calculating the true “charitable” portion of the deduction?[62] Calculating the precise benefit received from these tax deductions could be complicated in practice.[63] For simplicity’s sake, the federal government should consider overlooking these run-of-the-mill tax deductions in favor of a new rule focused only on state tax credits. Because such a distinction is not included in current law, however, this would likely require legislative action rather than new guidance or a regulation from the executive branch.[64] The IRS or Treasury Department would have a difficult time explaining why the federal charitable deduction must now be reduced when some types of tax benefits are received (e.g., large state tax credits, including the new workaround credits) but not others (e.g., smaller state tax credits, state tax deductions, or perhaps even the federal deduction itself).

One possible template for federal legislative action is Rep. Terri Sewell’s H.R. 4269, the Public Funds for Public Schools Act. [65] The bill, which was introduced prior to the enactment of the TCJA, deals only with state tax subsidies for donations to private K-12 school voucher funds. These types of donations were, and still are, the most common type of tax-credit-related abuse of the federal charitable deduction as they allow so-called “donors” in at least eleven states to receive tax cuts larger than the amount they donate.[66] Under H.R. 4269, taxpayers can receive a full federal charitable deduction even for donations to private school voucher funds that benefited from a state tax deduction. But the federal deduction is reduced in cases where the state tax benefit is provided in the form of a tax credit: under a 60 percent state tax credit, for example, only the 40 percent of the donation not offset by the credit would remain federally deductible. And to prevent gaming, the bill also claws back some or all of the federal charitable deduction if states offer deductions larger than the amount donated: say 200, or 300, or even 1000 percent of the donation. The basic structure contained in this bill could be expanded to apply not just to private school voucher credits, but to state charitable tax credits more broadly.

If Congress is interested in enacting a solution that would be even simpler to administer, it could write a law that only overlooks state tax benefits equal to, say, 20 percent or less of the amount donated. This would provide a level playing field across states where even the largest state tax deductions (taken against California’s top tax rate of 13.3 percent, for instance) would be allowed, as would any state credit or deduction of an equivalent amount. Any state tax benefit worth more than 20 percent of the donation, however, would require the taxpayer to calculate the precise amount of the state tax benefit they received and reduce their federal charitable deduction by a corresponding amount in order to arrive at the true “charitable” portion of the donation.

In the extreme cases of 100 percent personal income tax credits such as those received in return for donating to private school voucher funds in Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Montana, and South Carolina, the taxpayer would receive no federal charitable deduction because the donation amount is reimbursed in full by the state. In the context of New York’s new workaround credits, only the modest 15 percent of the donation not reimbursed by the state’s 85 percent tax credit would be considered a charitable gift for federal tax purposes.

One drawback of this approach is that it would create a modest “cliff effect,” where taxpayers who itemize at the federal level would find 20 percent state tax credits that are exempt from this new law to be more beneficial than somewhat larger state tax credits to which the law would apply. But this effect would be small in practice. For taxpayers in the top federal tax bracket of 37 percent, for instance, only credits in the range of 21-31 percent would be less beneficial than a 20 percent option. State credits of 32 percent and above would remain more beneficial than 20 percent credits despite being impacted by this new law.[67] And for states that offer, or wish to offer, credits in the range of 21-31 percent, the impact of this cliff could be mitigated by offering taxpayers the option of claiming a smaller, 20 percent credit, with the understanding that some itemizers may find it preferable to claim this smaller credit to remain below the federal threshold described above. Under the circumstances, this mild and partly avoidable cliff effect is a small price to pay for a dramatic and administratively feasible improvement to the federal charitable deduction’s measurement of true charity.

But while a 20 percent limit of this type may be the most targeted option available for resolving the specific problem at issue here, Congress may also consider taking this opportunity to reopen a broader debate over the $10,000 cap on the SALT deduction.

For starters, broader reform of the SALT cap will likely be needed anyway if lawmakers wish to close other widely recognized loopholes, such as the ability of states to shift away from deductible income taxes and toward deductible payroll taxes or business taxes designed to be nearly identical in their effect.[68]

In the context of the workaround credits, any reform that puts SALT payments and charitable gifts on an even footing under federal income tax law would effectively shut down the schemes described in this report. If charitable gifts were not treated more favorably than tax payments, then states and localities would have no reason to help their residents launder the latter into the former.

Ultimately, the SALT deduction and charitable deduction are similar in adjusting for taxpayers’ ability to pay federal income tax, and they often relate to funding for the same types of services, such as education and social services. While a detailed discussion of reforming itemized deductions more broadly is beyond the scope of this report, there are good reasons to consider putting these two deductions on a more even footing. Depending on the details, lifting the $10,000 SALT cap and replacing it with a broader limit on itemized deductions, or a new itemized deduction credit, could improve the yield and progressivity of the federal tax code while also ending the type of gaming outlined in this report.

Several states have responded to the new federal cap on SALT deductions by debating or enacting tax credits that allow their residents to claim federal charitable deductions on so-called “donations” that meet almost nobody’s definition of genuine charity. This abuse of the federal charitable giving deduction is certainly absurd, but it is far from new and seeking to shut down the new workaround credits without impacting any existing charitable giving credits would be ill-advised. Any attempt at a narrow fix will introduce more unfairness and arbitrariness into the federal tax code without actually stopping states from exploiting this broad and long-running loophole.

The surge of interest in these workaround credits should be used as an opportunity to fix a part of the federal tax code that is long-overdue for reform. Adding a more sophisticated measure of charitable giving into the tax code—one that considers significant state tax benefits received in return for donating—is necessary to ensure that the charitable giving deduction is reserved for its original purpose of encouraging actual philanthropy, not sophisticated tax sheltering. It is well within Congress’s power to implement this type of reform in an administratively simple fashion, though the ability of either the IRS or Treasury Department to do so on its own is much more doubtful.

Alternatively, Congress may consider using this debacle as an opportunity to revisit its hastily devised cap on the SALT deduction. Any itemized deduction reform that puts SALT payments and charitable donations an even footing would also have the effect of ending the type of gaming outlined in this report.

[1] Kamin, David and Gamage, David and Glogower, Ari D. and Kysar, Rebecca M. and Shanske, Darien and Avi-Yonah, Reuven S. and Batchelder, Lily L. and Fleming, J. Clifton and Hemel, Daniel Jacob and Kane, Mitchell and Miller, David S. and Shaviro, Daniel and Viswanathan, Manoj. “The Games They Will Play: Tax Games, Roadblocks, and Glitches Under the New Legislation.” First published Dec. 7, 2017. Last updated Feb. 26, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3089423.

[2] The value of the deduction depends on the taxpayer’s marginal federal income tax rate. The top tax rate for high-income taxpayers is 37 percent.

[3] Stein, Jeff. “California has a plan to skirt the GOP tax law. IRS veterans say it is likely doomed.” Washington Post Wonkblog. Feb. 12, 2018. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/02/12/california-has-a-plan-to-skirt-the-gop-tax-law-irs-veterans-say-its-doomed/.

[4] State of New York. S. 7509 / A. 9509. Jan. 18, 2018. Available at: http://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/s7509c.

[5] Indiana Department of Revenue. “Income Tax Credit for Donations to Colleges.” Informational Bulletin #14. July 2015. Available at: https://www.in.gov/dor/files/ib14.pdf.

[6] State of New Jersey 218th Legislature. Senate, No. 1893. Enacted May 4, 2018. Available at: http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S2000/1893_R1.PDF.

[7] State of Connecticut General Assembly, Session Year 2018. Substitute Senate Bill No. 11. Available at: https://www.cga.ct.gov/asp/cgabillstatus/cgabillstatus.asp?selBillType=Bill&which_year=2018&bill_num=11.

[8] Jones, Paul. “State Looks to Decouple From Federal Passthrough Deduction.” State Tax Notes. Mar. 5, 2018.

[9] State of Oregon 79th Legislative Assembly. Senate Bill 1528. Available at: https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2018R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/SB1528/Enrolled.

[10] Office of the State Treasurer of California. “College Access Tax Credit Fund.” Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: http://www.treasurer.ca.gov/cefa/fact_sheet.pdf.

[11] Davis, Carl. “State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Oct. 12, 2016. Available at: https://itep.org/state-tax-subsidies-for-private-k-12-education/.

[12] Jared Walczak of the Tax Foundation writes: “Public statements by the proponents of the strategy essentially admitting that as the goal would be instructive for an IRS action to disallow it.” See Walczak, Jared. “State Strategies to Preserve SALT Deductions for High-Income Taxpayers: Will They Work?” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 569. Jan. 5, 2018. Available at: https://taxfoundation.org/state-strategies-preserve-state-and-local-tax-deduction/. And Eric Rasmusen of Indiana University writes, regarding a hypothetical school voucher tax credit: “He does receive something of value from a third party, but that is okay. This is clearly not an attempt to use state laws to reduce the taxes of West Dakota residents.” See Rasmusen, Eric Bennett. “Getting Around the State and Local Tax Deduction Limit.” Kelley School of Business Research Paper No. 18-8. Jan. 9, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3099296.

[13] Crain, Trisha Powell. “$30 million in AAA tax credits already claimed for 2018.” AL.com. Apr. 27, 2018. Available at: http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2018/04/30_million_in_aaa_tax_credits.html.

[14] Davis, Carl. “Tax Bill Would Increase Abuse of Charitable Giving Deduction, with Private K-12 Schools as the Biggest Winners.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Dec. 14, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/tax-bill-would-increase-abuse-of-charitable-giving-deduction-with-private-k-12-schools-as-the-biggest-winners/.

[15] Ely, Bruce, Page Stalcup, Lesley Searcy, and Bri Jackson. “The New Federal Tax Law and Tax Credit Scholarship Donation Benefits for Alabama Taxpayers.” Presentation for the Alabama Opportunity Scholarship Fund. Feb. 16, 2018. Available at: https://alabamascholarshipfud.org/_pdfs/Tax_Credit_Scholarship_Donation_Webinar_02_16_2018.pdf. Hindsman, Todd. “Alabama Accountability Act – Tax Planning Opportunity for You.” Barfield, Murphy, Shank & Smith LLC. Feb. 1, 2018. Available at: http://bmss.com/alabama-accountability-act-tax-planning-opportunity/.

[16] For some discussion of this point, see pages 4 and 16 of: Colinvaux, Roger. “Failed Charity: Taking State Tax Benefits into Account for Purposes of the Charitable Deduction.” Buffalo Law Review, Forthcoming. Apr. 30, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3172179.

[17] Rasmusen, Eric Bennett. “Getting Around the State and Local Tax Deduction Limit.” Kelley School of Business Research Paper No. 18-8. Jan. 9, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3099296. Grewal, Andy. “Can States Game the Republican Tax Bill with the Charitable Contribution Strategy?” Notice & Comment, A Blog from the Yale Journal on Regulation. Jan. 3, 2018. Available at: http://yalejreg.com/nc/can-states-game-the-republican-tax-bill-with-the-charitable-contribution-strategy/. Walczak, Jared. “State Strategies to Preserve SALT Deductions for High-Income Taxpayers: Will They Work?” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 569. Jan. 5, 2018. Available at: https://taxfoundation.org/state-strategies-preserve-state-and-local-tax-deduction/. Faber, Peter L. “Do Charitable Contributions Avoid The TCJA SALT Deduction Limit?” State Tax Notes. Apr. 23, 2018.

[18] Faber, Peter L. “Do Charitable Contributions Avoid The TCJA SALT Deduction Limit?” State Tax Notes. Apr. 23, 2018.

[19] Pudelski, Sasha and Carl Davis. “Public Loss, Private Gain: How School Voucher Tax Shelters Undermine Public Education.” AASA and ITEP. May 17, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/public-loss-private-gain-how-school-voucher-tax-shelters-undermine-public-education/.

[20] Bankman, Joseph and Gamage, David and Goldin, Jacob and Hemel, Daniel Jacob and Shanske, Darien and Stark, Kirk J. and Ventry, Dennis J. and Viswanathan, Manoj. “Federal Income Tax Treatment of Charitable Contributions Entitling Donor to a State Tax Credit.” UCLA School of Law, Law-Econ Research Paper No. 18-02; UC Hastings Research Paper No. 264. Jan. 8, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3098291.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Credits for donating to school voucher organizations tend to offer the highest rates of return, with reimbursements up to 100 percent of the amount donated. But credits for donating to other causes are large enough that the IRS or Treasury would find it exceedingly difficult to ignore them entirely in targeted action. While it may be reasonable for the IRS to treat 100 percent credits differently than credits in the range of 1 to 99 percent on the grounds that 100 percent credits involve zero financial sacrifice by the donor, drawing a bright line at any other specific percentage is likely impossible via the regulatory process and is a task best left to Congress. This helps explain why many of the new workaround credits are set at levels somewhat below 100 percent. It will be difficult for the IRS to treat New York’s 85 percent workaround credit less favorably than Alabama’s 100 percent voucher credit or even Indiana’s 50 percent credit for donating to institutions of higher education.

[23] State of New York. S. 7509 / A. 9509. Jan. 18, 2018. Available at: http://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/s7509c.

[24] State of New Jersey 218th Legislature. Senate, No. 1893. Enacted May 4, 2018. Available at: http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S2000/1893_R1.PDF.

[25] State of Illinois 100th General Assembly. House Bill 4237. Introduced Jan. 11, 2018. Available at: http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?DocNum=4237&GAID=14&DocTypeID=HB&LegId=108676&SessionID=91&GA=100.

[26] State of Rhode Island, Session Year 2018. S. 2216. Feb. 1, 2018. Available at: http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText/BillText18/SenateText18/S2216.pdf.

[27] Council of the District of Columbia. B22-0667. Introduced Jan. 23, 2018. Available at: http://lims.dccouncil.us/Legislation/B22-0667.

[28] State of Oregon 79th Legislative Assembly. Senate Bill 1528. Available at: https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2018R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/SB1528/Enrolled.

[29] Office of the State Treasurer of California. “College Access Tax Credit Fund.” Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: http://www.treasurer.ca.gov/cefa/fact_sheet.pdf.

[30] Arkansas Economic Development Commission. “Rules.” May 4, 2016. Available at: http://www.arkansasedc.com/sites/default/files/content/users/lcogbill/2016_aedc_rules_book_may_4_2016.pdf.

[31] Tagami, Ty. “Lawmakers debate tax credit for school ‘innovation’ fund.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Mar. 21, 2017. Available at: https://www.ajc.com/news/state–regional-education/lawmakers-debate-tax-credit-for-school-innovation-fund/0xuUPUvO8bv64uxrrVPbPN/.

[32] Missouri Department of Agriculture. “Agricultural Products Utilization Contributor Tax Credit Program.” Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: http://agriculture.mo.gov/abd/financial/agproductcontr.php.

[33] Oregon Department of Education, Early Learning Division. “Child Care Contribution Tax Credit Overview.” Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://oregonearlylearning.com/administration/tax-credit/.

[34] Examples include Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, and Massachusetts. See Appendix A of: Bankman, Joseph and Gamage, David and Goldin, Jacob and Hemel, Daniel Jacob and Shanske, Darien and Stark, Kirk J. and Ventry, Dennis J. and Viswanathan, Manoj. “Federal Income Tax Treatment of Charitable Contributions Entitling Donor to a State Tax Credit.” UCLA School of Law, Law-Econ Research Paper No. 18-02; UC Hastings Research Paper No. 264. Jan. 8, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3098291.

[35] Indiana Department of Revenue. “Income Tax Credit for Donations to Colleges.” Informational Bulletin #14. July 2015. Available at: https://www.in.gov/dor/files/ib14.pdf.

[36] A list of “qualified educational entities” in Idaho is printed on page 25 of the state’s 2017 income tax instruction booklet, available at: https://tax.idaho.gov/forms/EIN00046_10-12-2010.pdf.

[37] La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §47:37. Available at: http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/Law.aspx?d=102097

[38] “Enterprise Zone Administrators.” ChooseColorado.com. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://choosecolorado.com/doing-business/incentives-financing/ez/administrators/.

[39] Neb. Rev. Stat. §13-203.

[40] Indiana Department of Revenue. “Indiana College Credit.” Schedule CC-40. State Form 20152. R13 / 9-17. 2017. Available at: https://www.in.gov/dor/files/20152-2017.pdf.

[41] State of New York. S. 7509 / A. 9509. Jan. 18, 2018. Available at: http://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/s7509c.

[42] Julian, Sarah. “Supporting innovation in Oklahoma’s rural schools.” Oklahoma Policy Institute, guest blog post. Dec. 10, 2014. Available at: https://okpolicy.org/supporting-innovation-oklahomas-rural-schools-guest-post-sarah-julian/.

[43] State of Connecticut General Assembly, Session Year 2018. Substitute Senate Bill No. 11. Available at: https://www.cga.ct.gov/asp/cgabillstatus/cgabillstatus.asp?selBillType=Bill&which_year=2018&bill_num=11.

[44] Missouri Department of Economic Development. “Innovation Campus Program.” Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://ded.mo.gov/programs/community/innovation-campus-program.

[45] NetWork Kansas. “About Us.” NetWorkKansas.com Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://www.networkkansas.com/about.

[46] Kansas Department of Commerce. “Network Kansas.” KansasCommerce.gov. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://www.kansascommerce.gov/209/NetWork-Kansas.

[47] Cultural Trust. “Who We Are.” CulturalTrust.org. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: http://culturaltrust.org/about-us/who-we-are/.

[48] South Carolina Research Authority. “How to Contribute.” SCRA.org. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://scra.org/what-we-do/support-entrepreneurs/how-to-contribute.

[49] South Carolina Department of Revenue. “Exceptional SC.” DOR.SC.gov. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://dor.sc.gov/exceptional-sc.

[50] Faber, Peter L. “Do Charitable Contributions Avoid The TCJA SALT Deduction Limit?.” State Tax Notes. Apr. 23, 2018.

[51] Illinois is the most recent state to enact such a credit. The other seventeen states are identified in: Davis, Carl. “State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Oct. 12, 2016. Available at: https://itep.org/state-tax-subsidies-for-private-k-12-education/.

[52] See Appendix A of: Bankman, Joseph and Gamage, David and Goldin, Jacob and Hemel, Daniel Jacob and Shanske, Darien and Stark, Kirk J. and Ventry, Dennis J. and Viswanathan, Manoj. “Federal Income Tax Treatment of Charitable Contributions Entitling Donor to a State Tax Credit.” UCLA School of Law, Law-Econ Research Paper No. 18-02; UC Hastings Research Paper No. 264. Jan. 8, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3098291. A few examples of such programs include tax credits for contributions to the following programs: Arizona foster care, Colorado child care, Idaho youth facilities and substance abuse centers, Missouri child services and maternity homes, and Utah disability services.

[53] Missouri Department of Social Services. “Residential Treatment Tax Credit.” DSS.MO.gov. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://dss.mo.gov/dfas/taxcredit/restreatment.htm.

[54] Missouri Department of Economic Development. “Youth Opportunity Program.” DED.MO.gov. Accessed Apr. 23, 2018. Available at: https://ded.mo.gov/programs/community/YOP.

[55] Indiana Department of Revenue. “Individual Development Account Tax Credit Application.” Form IDA-10/20. SF 48770. R2/8-05. Available at: https://forms.in.gov/download.aspx?id=2693.

[56] California Legislature, 2017-2018 Regular Session. Assembly Bill No. 2217. Amended May 2, 2018. Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB2217.

[57] Grewal, Andy. “Can States Game the Republican Tax Bill with the Charitable Contribution Strategy?” Notice & Comment, A Blog from the Yale Journal on Regulation. Jan. 3, 2018. Available at: http://yalejreg.com/nc/can-states-game-the-republican-tax-bill-with-the-charitable-contribution-strategy/.

[58] Rasmusen, Eric Bennett. “Getting Around the State and Local Tax Deduction Limit.” Kelley School of Business Research Paper No. 18-8. Jan. 9, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3099296.

[59] Faber, Peter L. “Comment on Professor Stark’s Prompt.” 9 Colum. J. Tax L. Tax Matters 9. Available at: https://taxlawjournal.columbia.edu/article/comment-on-professor-starks-prompt/.

[60] Faber, Peter L. “Do Charitable Contributions Avoid The TCJA SALT Deduction Limit?” State Tax Notes. Apr. 23, 2018.

[61] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “State Treatment of Itemized Deductions.” Jun. 2, 2016. Available at: https://itep.org/state-treatment-of-itemized-deductions-1/.

[62] Bankman, Joseph, David Gamage, Jacob Goldin, Daniel J. Hemel, Darien Shanske, Kirk J. Stark, Dennis J. Ventry Jr., and Manoj Viswanathan. “Caveat IRS: Problems With Abandoning the Full Deduction Rule.” Tax Notes. May 7, 2018.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] 115th US Congress (2017-2018). “Public Funds for Public Schools Act.” H.R. 4269. Introduced Nov. 7, 2017. Another aspect of this bill relates to donations of stock or other property, which some taxpayers can effectively “sell,” tax-free, by donating the property to a nonprofit and then receiving a full payment in the form of tax-free state charitable tax credits. This type of abuse is discussed in more detail in: Davis, Carl. “Tax Bill Would Increase Abuse of Charitable Giving Deduction, with Private K-12 Schools as the Biggest Winners.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Dec. 14, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/tax-bill-would-increase-abuse-of-charitable-giving-deduction-with-private-k-12-schools-as-the-biggest-winners/. Davis, Carl. “Private School Voucher Credits Offer a Windfall to Wealthy Investors in Some States.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Aug. 30, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/private-school-voucher-credits-offer-a-windfall-to-wealthy-investors-in-some-states/.

[66] Those states are Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Montana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia. Louisiana’s credit became newly profitable because of recent state legislative changes and is not described in the following report: Davis, Carl. “Tax Bill Would Increase Abuse of Charitable Giving Deduction, with Private K-12 Schools as the Biggest Winners.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Dec. 14, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/tax-bill-would-increase-abuse-of-charitable-giving-deduction-with-private-k-12-schools-as-the-biggest-winners/.

[67] Under this potential law, a 32 percent credit would result in the taxpayer being able to deduct 68 percent of their donation at the federal level. For a high-income taxpayer deducting $68 of a $100 donation against a 37 percent federal tax rate, the federal savings associated with donating would be $25.16 which, when added to the $32 state tax credit, would result in $57.16 in tax savings overall. For a high-income taxpayer receiving only a 20 percent state credit and deducting the full $100 at the federal level, the savings would be $20 at the state level and $37 at the federal level, or a slightly smaller $57 overall.

[68] Kamin, David and Gamage, David and Glogower, Ari D. and Kysar, Rebecca M. and Shanske, Darien and Avi-Yonah, Reuven S. and Batchelder, Lily L. and Fleming, J. Clifton and Hemel, Daniel Jacob and Kane, Mitchell and Miller, David S. and Shaviro, Daniel and Viswanathan, Manoj. “The Games They Will Play: Tax Games, Roadblocks, and Glitches Under the New Legislation.” First published Dec. 7, 2017. Last updated Feb. 26, 2018. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3089423.