Summary

The Educational Choice for Children Act of 2025 (ECCA) would ostensibly provide a tax break on charitable donations to organizations that give out private K-12 school vouchers. Most of the so-called “contributions,” however, would be made by wealthy people solely for the tax savings, as those savings would typically be larger than their contributions.

ITEP estimates that ECCA would spur $126 billion in contributions to private school voucher funds over the next 10 years but would cost the U.S. Treasury more than that—$134 billion—because the tax subsidies being paid out would exceed the contributions made to these funds. Most states would automatically provide additional tax breaks on top of those offered by the federal government, bringing the total loss to public budgets to over $136 billion. In effect, ECCA seeks to harness wealthy families’ interest in tax avoidance and personal profit as a means of bolstering private schools at the expense of public budgets.

Key Findings

- The Educational Choice for Children Act of 2025 (ECCA) would use the tax code to privilege nonprofit organizations that give out private K-12 school vouchers over nonprofits working on other issues, such as those supporting wounded veterans or victims of natural disasters. It would do this by reimbursing donors to voucher-bundling groups, in full, with an unprecedented dollar-for-dollar federal tax credit.

- In addition to the federal government covering the complete cost of the contributions to voucher-bundling groups, contributors would be able to reduce their taxes further by contributing corporate stock and avoiding capital gains tax. This would allow wealthy “donors” to turn a profit, at taxpayer expense, by acting as middlemen in steering federal funding into private K-12 schools. ECCA’s supporters appear to be counting on this tax shelter as a means of driving donor interest in the program even as vouchers remain unpopular with the public.

- The nation’s wealthiest families would enjoy substantial tax avoidance opportunities under ECCA. For example, if ECCA had been in effect a few years ago, voucher-proponents Betsy DeVos and Jeffrey Yass would likely have claimed annual tax credits of $11.2 million and $130 million per year, respectively. Capital gains tax avoidance would have come on top of these tax credits and could be expected to result in roughly $1.4 million of annual profit for DeVos and $13.3 million of annual profit for Yass.

- The centerpiece of ECCA is $10 billion in annual tax credits. The bill’s true cost is higher and would grow rapidly over time. We estimate that by 2035, the annual cost to federal and state coffers would be $17 billion. In total, ECCA would cost the federal government $134 billion in foregone revenue over the next 10 years and would cost states an additional $2.3 billion. This amounts to a combined loss to public revenue of $136.3 billion over the next decade.

- This money would flow from the public to three main groups of beneficiaries: private schools, voucher-bundling organizations, and wealthy donors. Eighty-five percent ($115.7 billion) of the foregone revenues would be converted into vouchers, 7 percent ($10.1 billion) would go toward the cost of administering these vouchers, and 8 percent ($10.5 billion) would flow to wealthy families as personal profit.

Overview of the Tax Provisions in the ECCA

The Education Choice for Children Act of 2025 (ECCA) has been introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives as H.R. 833 and in the U.S. Senate as S. 292. The bill proposes a 100 percent tax credit—that is, a full reimbursement—for “donations” to nonprofits known as Scholarship Granting Organizations (SGOs). These SGOs are tasked with bundling the donations and converting them, primarily, into vouchers for free or reduced tuition at private K-12 schools.[1]

The bill’s provision of a 100 percent tax credit is a sharp departure from how the federal government treats most types of contributions to nonprofit organizations. Typically, people contributing to nonprofits receive, at most, a tax deduction valued at 37 cents per dollar donated. Under this bill, “donors” to private K-12 school voucher funds would receive a tax break worth 100 cents per dollar donated—or roughly triple what they could receive by contributing to support wounded veterans, survivors of domestic violence, victims of natural disasters, or other nonprofit endeavors.

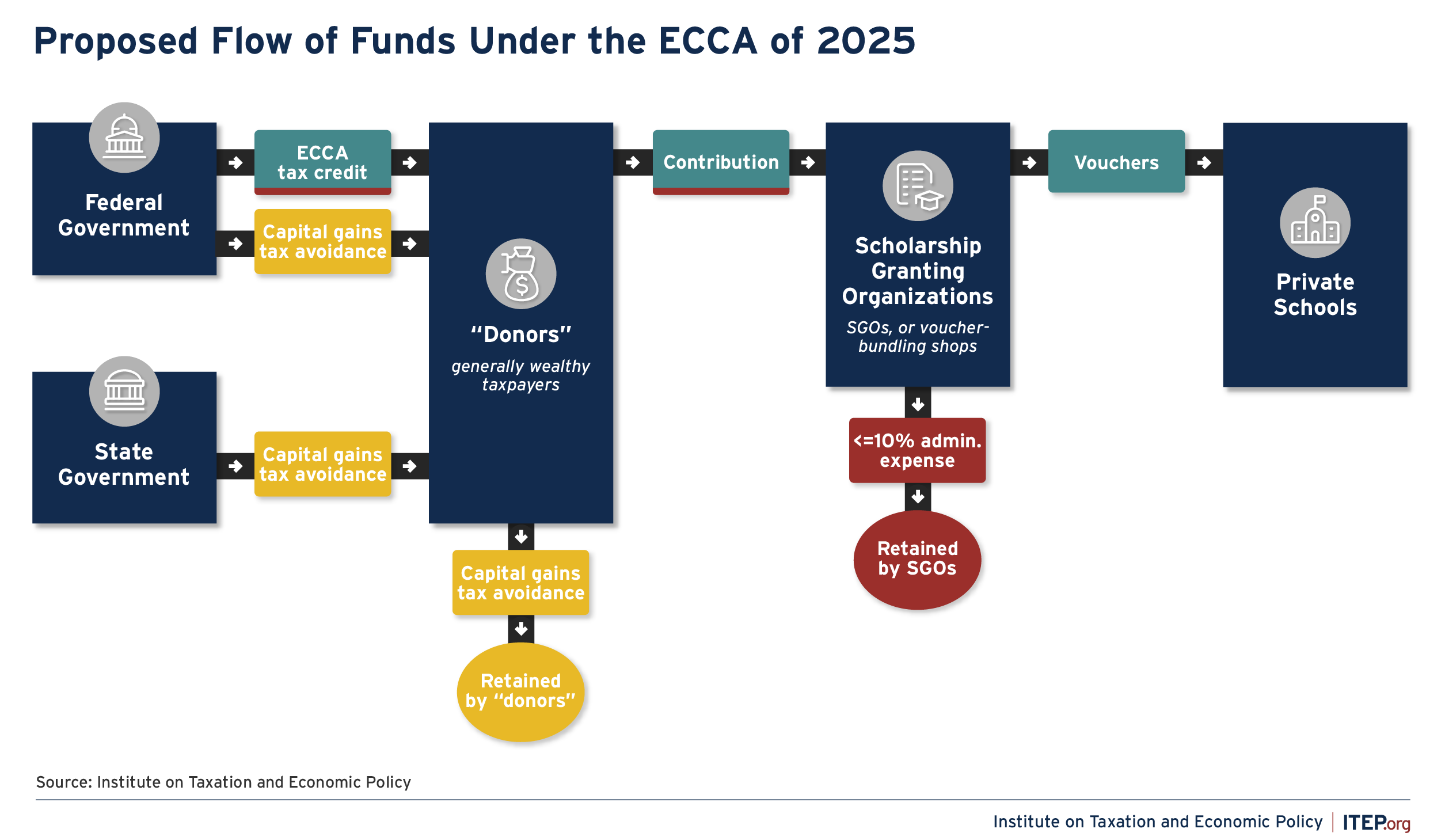

FIGURE 1

An overview of the path taken by these public dollars is provided in Figure 1. In short, the federal government would provide tax cuts to wealthy individuals and, in many cases, states would automatically pile on with additional tax cuts of their own. The people receiving these tax cuts would direct most of them to SGOs to fund private K-12 school vouchers, while retaining a portion for themselves as personal profit. And finally, the SGOs would direct most of the dollars they receive to private schools while retaining a portion for themselves to pay their employees and cover other administrative expenses.

Description of Capital Gains Tax Shelter

Contributions to SGOs under ECCA could take the form of either cash or marketable securities, such as corporate stock. In practice, the vast majority of contributions would be corporate stock because the tax subsidy for stock contributions is far larger than the subsidy for cash contributions.[2]

In fact, the tax cuts tied to stock contributions are so large that contributors would generally find that “donating” would yield a personal profit for themselves. That is, the financial return from “donating” stock to SGOs would be larger than the financial return of selling the stock in exchange for cash.

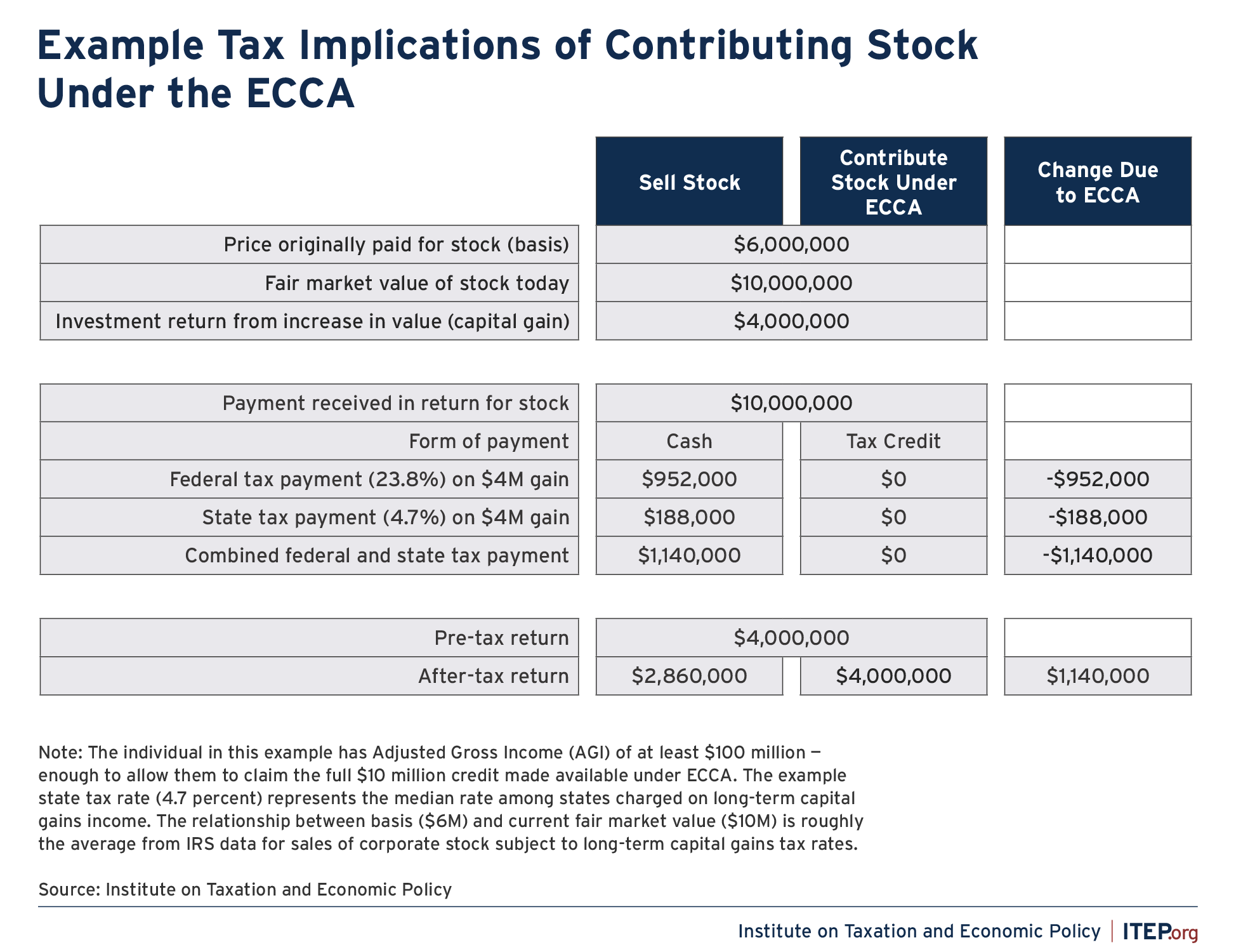

This effect is illustrated with an example in Figure 2. In it, an individual who initially purchased stock for $6 million has seen it grow in value to $10 million, resulting in $4 million of profit. This $4 million return would ordinarily be considered long-term capital gains and subject to a federal income tax rate of 23.8 percent upon sale, resulting in a federal tax bill of $952,000. State taxes could add another $188,000 to that total, depending on the taxpayer’s state of residence.[3] The total federal and state tax bill on this sale would therefore be $1.14 million.

Under the ECCA, a taxpayer in this situation would likely be advised by their accountant to forgo selling this stock in favor of contributing it to an SGO instead. Claiming an ECCA tax credit would result in the same pre-tax return as selling the stock (receipt of a $10 million tax credit rather than a $10 million cash payout). But it would not incur the $1.14 million income tax bill described above and depicted in Figure 2. This taxpayer therefore sees a higher after-tax return, or profit, from choosing to give away their stock under ECCA rather than sell their stock.

FIGURE 2

The tax structure envisioned under ECCA is a classic example of a “tax shelter,” as it would attract not just people who care deeply about funding private K-12 school vouchers, but also opportunists who would participate solely for the tax savings.[4] There is a long history of private schools and financial advisors advertising various kinds of tax shelters hidden in state-level tax credits similar to ECCA.[5]

Up until a few months ago, ECCA supporters might have been forgiven for proposing such an egregious tax shelter on the grounds that, perhaps, they were simply unaware of what they were suggesting. They lost all claim to plausible deniability last fall, however, when Republicans on the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee voted along party lines against a technical correction from Rep. Mike Thompson that would have stripped this tax shelter from the bill while leaving the tax credits and the rest of the legislation intact.[6] Apparently, the bill’s supporters are counting on harnessing this tax shelter as a powerful incentive to fuel their efforts at school privatization.[7]

Illustrating ECCA’s Impact for Prominent Voucher Proponents

Enacting ECCA would almost certainly inspire a flood of donations of corporate stock not just by people who support private school vouchers, but also by wealthy people who are merely acting on the advice of their financial advisors. Nevertheless, wealthy people with a genuine interest in school privatization are almost certain to be among the most enthusiastic ECCA tax credit claimants.

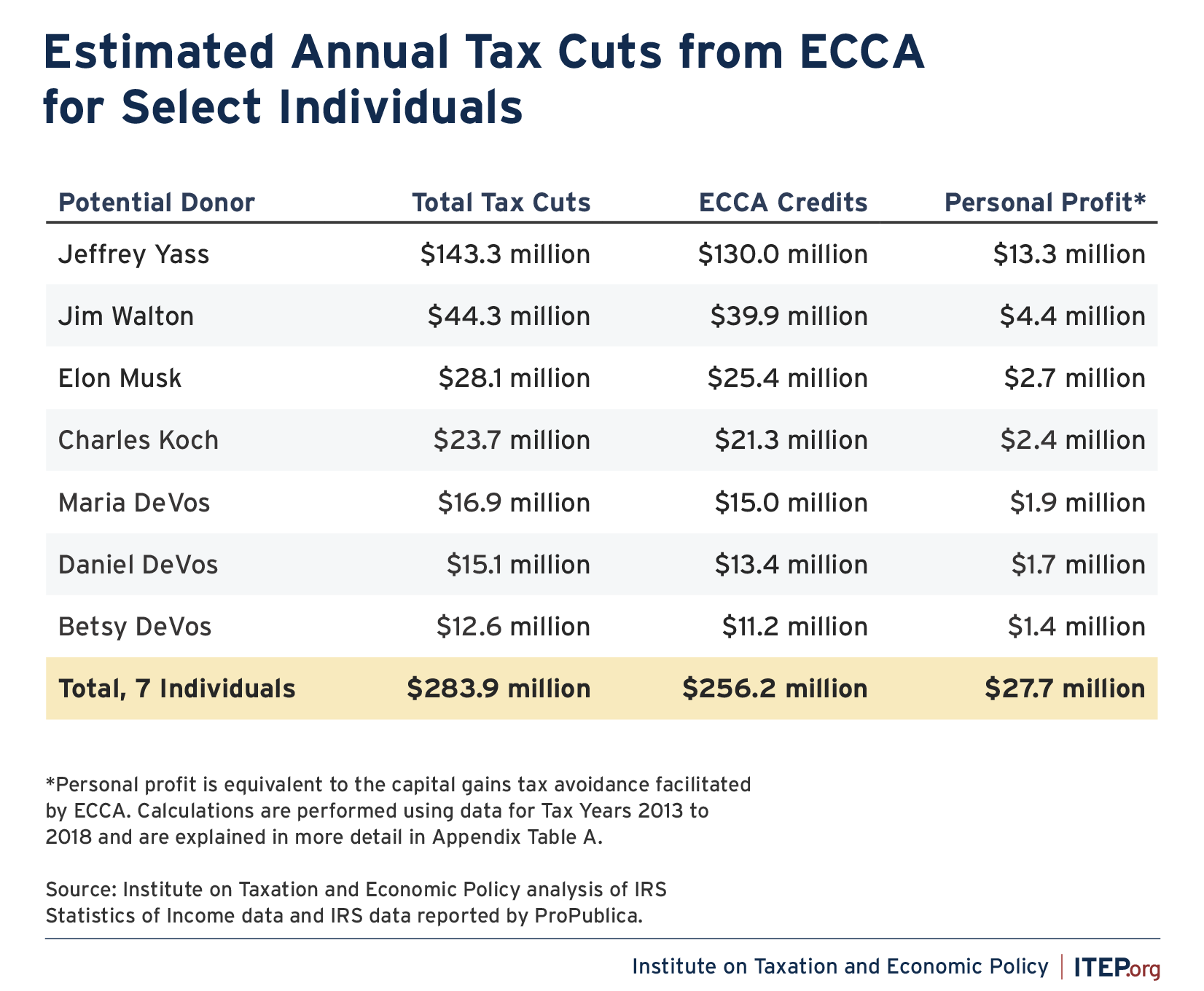

To illustrate the tax impacts of the ECCA more clearly, we compute the bill’s likely effects for seven wealthy individuals who have gone on the record as supporting public funding of private school vouchers, and are therefore extremely likely to claim ECCA tax credits if they are enacted.[8] The analysis presented in Figure 3 combines IRS tax data reported by ProPublica with IRS statistical data to estimate the approximate tax cuts that wealthy voucher proponents could have received each year if ECCA were in effect from 2013 to 2018 (the years of data reported by ProPublica).[9]

FIGURE 3

We estimate that if this proposal had been in effect during those years, Betsy DeVos would have claimed a tax credit of $11.2 million per year and Jeffrey Yass would have claimed $130 million per year. Capital gains tax savings would have come on top of these tax credit amounts and could be expected to result in a $1.4 million annual profit for DeVos and a $13.3 million annual profit for Yass.

Altogether, the seven individuals examined here would have received $283.9 million in tax cuts per year. Of that amount, $256.2 million would be reimbursement, in full, for their contributions to SGOs while the other $27.7 million would be personal profit in the form of capital gains tax avoidance.

It bears noting that the assumptions used to arrive at these estimates may underestimate the tax cuts these individuals could expect under ECCA.[10] Most notably, the tax cuts afforded to them today would likely be larger than is shown here simply because the wealth, and likely the income, of most of these individuals has grown substantially since the period covered by the ProPublica reporting.[11] Elon Musk’s overall wealth, for example, was 21 times higher in 2024 than it was in 2016, according to estimates by Forbes.[12]

Actual tax credit claims are also likely to vary significantly across years, as the taxable incomes of wealthy people fluctuate based on when they decide to sell their investment holdings. In 2018, for example, Elon Musk would likely have been ineligible to claim ECCA credits, based on reporting by ProPublica that he paid no federal income tax that year.[13] In 2021, on the other hand, Musk could potentially have claimed $2.9 billion in ECCA credits, or nearly 30 percent of the total amount available nationwide.[14] A claim of that magnitude could have allowed Musk to avoid $690 million in federal personal income tax on his capital gains income.

Federal and State Revenue Effects

While the centerpiece of ECCA is $10 billion in annual tax credits, the bill’s true cost is higher and would grow quickly over time.

As described above, for instance, ECCA would facilitate avoidance of both federal and state capital gains taxes. That tax avoidance would result in additional revenue loss beyond the tax credits being provided.

ECCA also contains an escalator clause that would allow the amount of federal tax credits to automatically rise by 5 percent in any year where a large share (at least 90 percent) of the previous year’s credits were claimed. Given the lucrative nature of the capital gains tax shelter embedded in ECCA, it is virtually guaranteed that the entirety of available credits would be claimed each year and that this escalator provision would be repeatedly triggered.

Experience has shown that tax avoidance opportunities of the type contained in ECCA attract significant interest. In 2018, for example, a change in federal law ramped up the profitability of a tax shelter facilitated by a voucher tax credit in Arizona. Afterwards, taxpayers who had previously taken six months to claim the full allotment of state tax credits rushed to do so in just two minutes.[15] ECCA contains a similar “first-come, first-served” application process to ration what is sure to be a highly sought-after tax shelter.

Proponents of ECCA would likely cite a rapid claims process as evidence that vouchers are popular among taxpayers—despite their poor track record at the ballot box.[16] The reality, however, is that much of the enthusiasm among credit claimants would be driven by the personal self-interest of contributors seeking to exploit a profitable tax shelter.

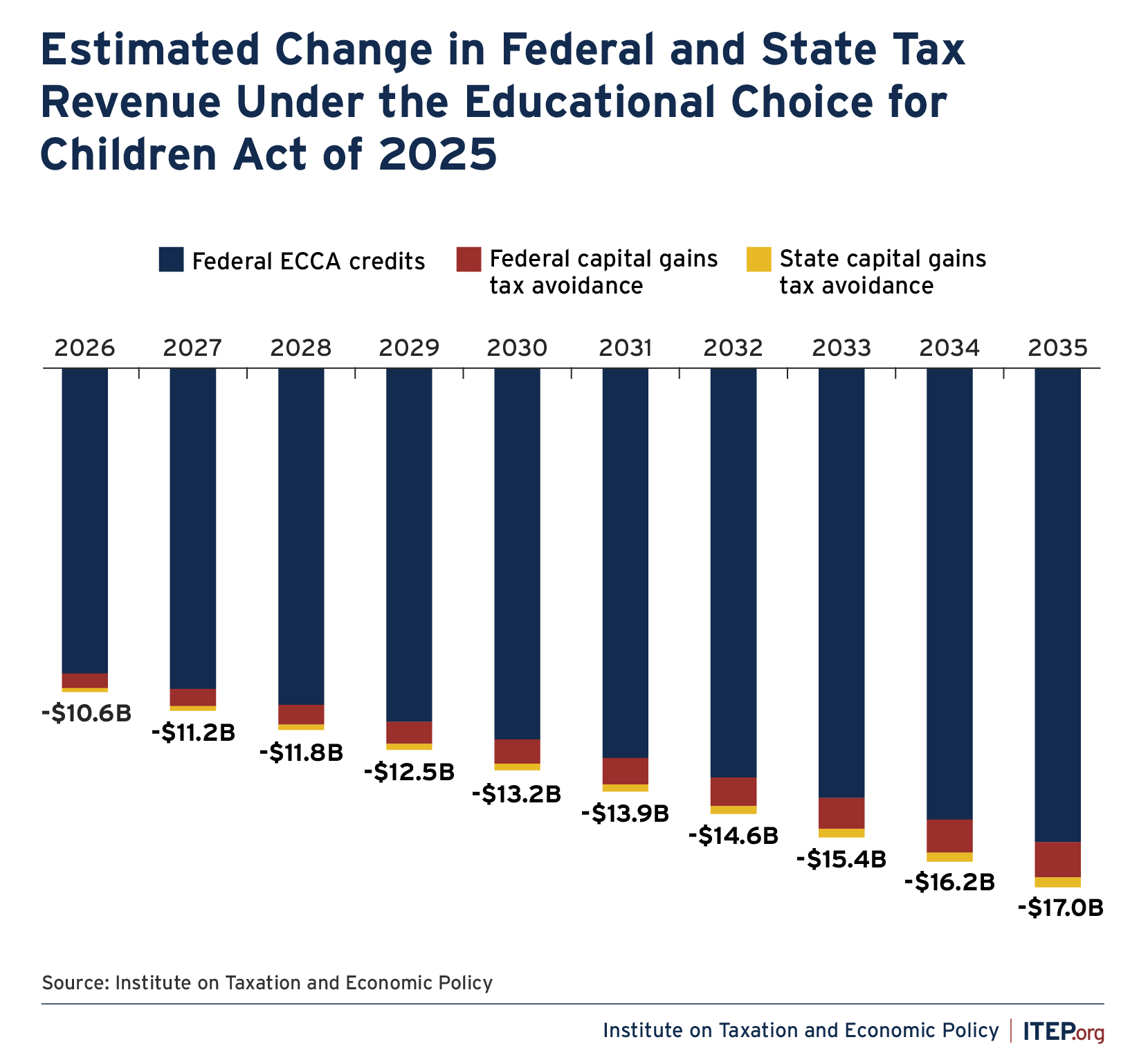

We estimate that by 2035, the annual cost of ECCA to federal and state coffers would be $17 billion.[17] By that time, just under 9 percent (or $1.5 billion) of the annual tax cuts facilitated by the bill would take the form of capital gains tax avoidance, with the other 91 percent resulting from the ECCA credits.

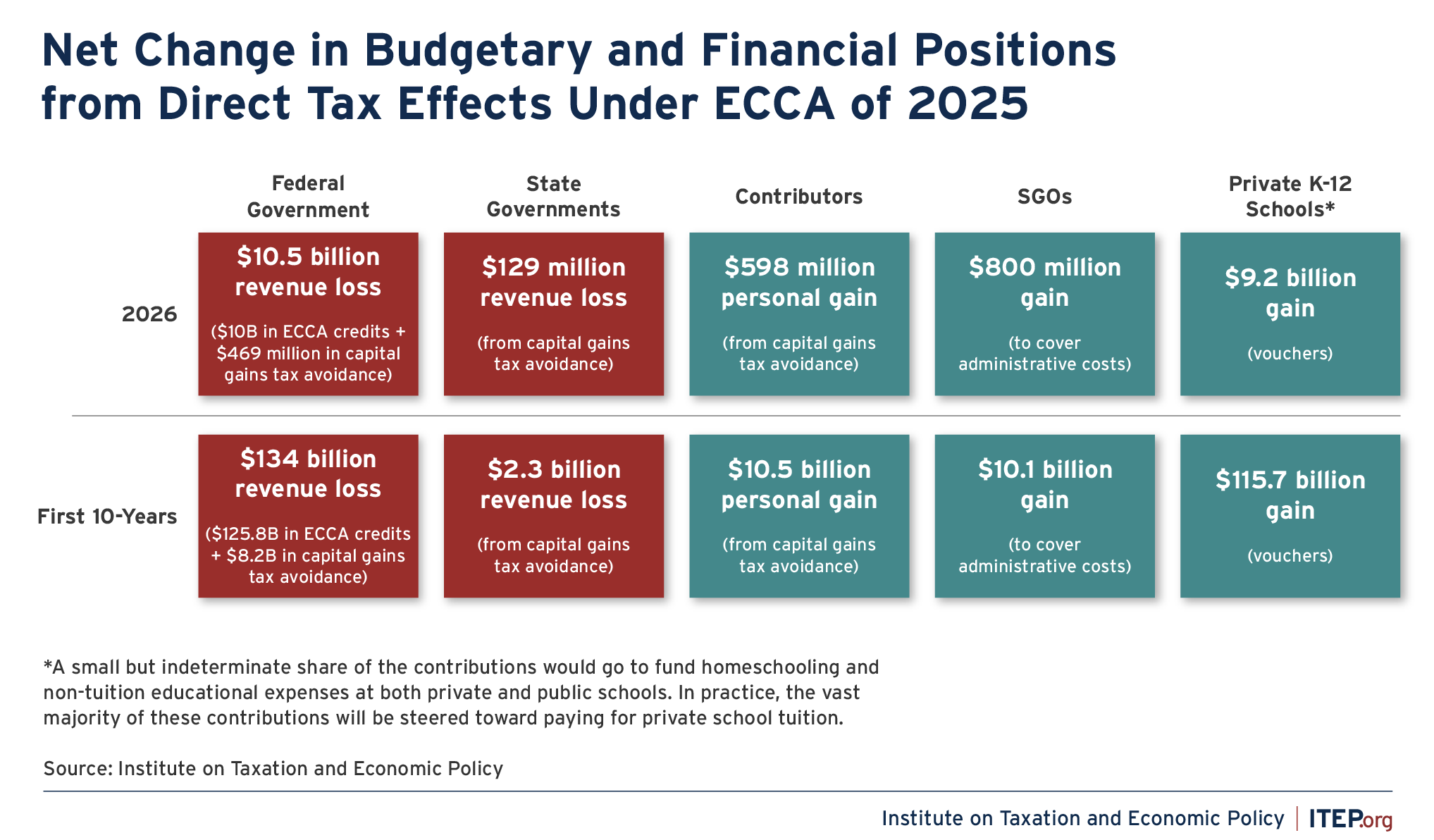

FIGURE 4

In total, ECCA would cost the federal government $134 billion in foregone revenue over the next 10 years and would cost states an additional $2.3 billion over that same period. This amounts to a combined loss to public coffers of $136.3 billion over the next decade. A detailed accounting of these effects, by year, is available in Appendix Table B. Results by state can be found in Appendix Table C.

Flow of Public Dollars into Private Schools

The convoluted nature of ECCA, involving transfers to and from at least five different actors (see Figure 1 earlier in this report), can make it difficult for interested parties to understand how the program would work in practice. Figure 5 sheds light on this question by showing how the tax policy aspects of ECCA would affect the budgetary or financial standing of the federal government, state governments, contributors, SGOs, and private schools. Clearly, the principal effect of ECCA is a significant transfer of public funds from the federal government into private K-12 schools.

Over the next decade, ECCA would move $134 billion out of federal coffers and an additional $2.3 billion out of state government coffers. Most of this movement (92 percent) is comprised of the ECCA credits but capital gains tax avoidance contributes 8 percent to this loss of funding as well. The combined federal and state effect would be a loss to public coffers of $136.3 billion over the next decade.

FIGURE 5

This expense to public budgets would flow to three main groups of beneficiaries: private schools, voucher-bundling organizations (SGOs), and wealthy contributors to those SGOs. Eighty-five percent (or $115.7 billion) of the foregone revenues would be converted into vouchers. Seven percent (or $10.1 billion) would go toward the cost of administering these vouchers.[18] And 8 percent (or $10.5 billion) would flow to wealthy families as capital gains tax avoidance.

Put a different way, ITEP estimates that ECCA would spur $126 billion in contributions to private school vouchers funds over the next 10 years but would cost the U.S. Treasury more than that—$134 billion—because the tax subsidies being paid out would exceed the contributions made to these funds. Most states would automatically provide additional tax breaks on top of those offered by the federal government, bringing the total loss to public budgets to $136.3 billion.

A more detailed, annual accounting of these figures can be found in Appendix Table B for the federal and state governments, and in Appendix Table D for contributors, SGOs, and private K-12 schools.

Conclusion

The Educational Choice for Children Act of 2025 (ECCA) would create an unprecedented dollar-for-dollar federal tax credit for people who contribute to voucher-bundling groups. The bill would privilege funding private K-12 school education over contributions to any other cause, such as supporting wounded veterans, survivors of domestic violence, or people reeling from natural disasters. In addition to offering these large tax credits, the bill would also open a new tax shelter that wealthy investors would use to avoid capital gains tax. In effect, the bill sponsors are proposing to wield the opportunity for tax avoidance to motivate wealthy families to act as middlemen in moving public funds into private schools. The result would be a significant loss to public revenues, estimated at over $136 billion over the next decade.

Appendix: Additional Data Tables

- Appendix Table A: Estimated Annual Tax Cuts from ECCA, if it Were in Effect Between 2013 and 2018, for Select Individuals

- Appendix Table B: Estimated Change in Federal and State Government Revenue Under ECCA of 2025

- Appendix Table C: State Revenue Loss from Capital Gains Tax Avoidance Facilitated by ECCA of 2025

- Appendix Table D: Estimated Change in Financial Position of Actors Benefiting from ECCA of 2025

Endnotes

[1] While the contributions can also be used to fund homeschooling and educational expenses other than private school tuition, in practice the vast majority of these contributions will be steered toward paying for private school tuition.

[2] Davis, Carl. “A Revenue Impact Analysis of the Educational Choice for Children Act of 2025.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. March 2025.

[3] This calculation was performed assuming a 4.7 percent tax rate, which is the median state tax rate applied to long-term capital gains income, as calculated by ITEP using a combination of data from NBER’s TAXSIM and information from state revenue agencies.

[4] While the phrase “tax shelter” does not have a universally agreed upon definition, one common theme in definitions is that it is often used to describe actions undertaken largely, or exclusively, for tax avoidance purposes. 26 U.S. Code §6662(d)(2)(C)(ii), for example, offers a definition of “tax shelter” that includes “any investment plan or arrangement… if a significant purpose of such… plan, or arrangement is the avoidance or evasion of Federal income tax.”

[5] Davis, Carl. “State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. May 2017.

Pudelski, Sasha and Carl Davis. “Public Loss Private Gain: How School Voucher Tax Shelters Undermine Public Education.” Joint report by the School Superintendents Association and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. May 2017.

Davis, Carl. “The Other SALT Cap Workaround: Accountants Steer Clients Toward Private K-12 Voucher Tax Credits.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. June 2018.

Davis, Carl. “Tax Avoidance Continues to Fuel School Privatization Efforts.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. March 2023.

[6] The relevant portion of the September 2024, U.S. House Ways & Means Committee hearing on a previous version of ECCA (H.R. 9462 of the 118th Congress) can be viewed here.

[7] Barkan, Joanne. “Death by a Thousand Cuts: The Story of Privatizing Public Education in the USA.” Washington Post. May 2018.

[8] Loftus, Tom. “Yass gives $5 million to PAC trying to sway Kentuckians to vote for school amendment.” Pennsylvania Capital-Star. October 2024.

Hardy, Benjamin and Griffin Coop. “Jim Walton gives $500K to defend Arkansas school vouchers from ballot measure.” Arkansas Times. May 2024.

Musk, Elon. Social media post.

Ho, Sally. “Powerful Koch network taking on school choice with new group.” Associated Press. July 2019.

Oosting, Jonathan. “Betsy DeVos-backed school voucher-like plan for Michigan submits petitions.” Bridge Michigan.

Michigan Committee Statement Contributions to Let MI Kids Learn. Michigan Secretary of State. April 2022.

Kingkade, Tyler. “A Betsy DeVos-backed group helps fuel a rapid expansion of public money for private schools.” NBC News. March 2023.

[9] The data published by ProPublica provide income amounts for 42 named individuals. This list was crosschecked against a variety of public information to identify the seven individuals examined here who have voiced support for private school voucher programs. See: Kiel, Paul, Ash Ngu, Jesse Eisinger, and Jeff Ernsthausen. “America’s Highest Earners And Their Taxes Revealed.” ProPublica. April 2022.

[10] One issue, for instance, is that we assume the stock contributed by these individuals reflects the average level of capital gains generated by corporate stock sales in general. In reality, these individuals would be incentivized to contribute their most highly-appreciated stock under ECCA to maximize the amount of capital gains tax they avoid.

[11] Peterson-Withorn, Chase. “Forbes 400: The Full List Of The Richest People in America 2016.” Forbes. October 2016.

Peterson-Withorn, Chase. “Forbes 400: The Definitive Ranking of America’s Richest People 2024.” Forbes. October 2024.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Eisinger, Jesse, Jeff Ernsthausen, and Paul Kiel. “The Secret IRS Files: Trove of Never-Before-Seen Records Reveal How the Wealthiest Avoid Income Tax.” ProPublica. June 2021.

[14] CNN reporting indicates that in 2021, Elon Musk collected $23.5 billion in taxable income from stock options and $5.8 billion in taxable income from stock sales. Summing these two figures suggests taxable income of roughly $29 billion that year, which is plausible based on Musk’s statement that he paid $11 billion of income taxes in 2021. A person with $29 billion of income could claim up to $2.9 billion in ECCA credits under the proposal examined in this report. If we assume Musk’s contributions under ECCA would have taken the form of Tesla stock acquired at the time of the company’s initial public offering, which appears likely based on CNN reporting, then nearly all the contribution value would have otherwise been considered long-term capital gains income and the act of contributing would have facilitated the avoidance of $690 million in federal personal income tax.

Isidore, Chris. “How Elon Musk sold 10 million Tesla shares and increased his Tesla holdings.” CNN. December 2021.

Isidore, Chris. “Elon Musk’s US tax bill: $11 billion. Tesla’s: $0.” CNN. February 2022.

[15] Davis, Carl. “ITEP Comments and Recommendations on Proposed Section 170 Regulation (REG-112176-18).” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. October 2018.

[16] Hager, Eli and Jeremy Schwartz. “Despite Trump’s Win, School Vouchers Were Again Rejected by Majorities of Voters.” ProPublica. November 2024.

[17] See note 2.

[18] ECCA permits SGOs to retain up to 10 percent of the donations they receive to cover their administrative expenses, though evidence from the states suggests that SGOs are likely to retain somewhat less than the 10 percent limit. Iowa Department of Revenue data indicate that these organizations retain 8 percent of their donations to cover administrative expenses while Pennsylvania’s Independent Fiscal Office has reported shares ranging from 7.5 to 8.8 percent across different credit types. With these figures in mind we assign 8 percent of ECCA credits to the payment of administrative costs. The overall total share of the public revenue loss ends up being slightly lower than 8 percent, however, because all of the capital gains tax avoidance is directed to contributors and none is directed toward paying administrative costs.

Girardi, Anthony G. and Angela Gullickson. “Iowa’s School Tuition Organization Tax Credit: Tax Credits Program Evaluation Study.” Iowa Department of Revenue. December 2017.

Toth, Robyn. “Pennsylvania Educational Tax Credits: An Evaluation of Program Performance.” Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Independent Fiscal Office. January 2022.