Key findings

• Expanding the federal Child Tax Credit to 2021 levels would help nearly 60 million children next year. It would help the lowest-income children the most and would particularly help children and families of color.

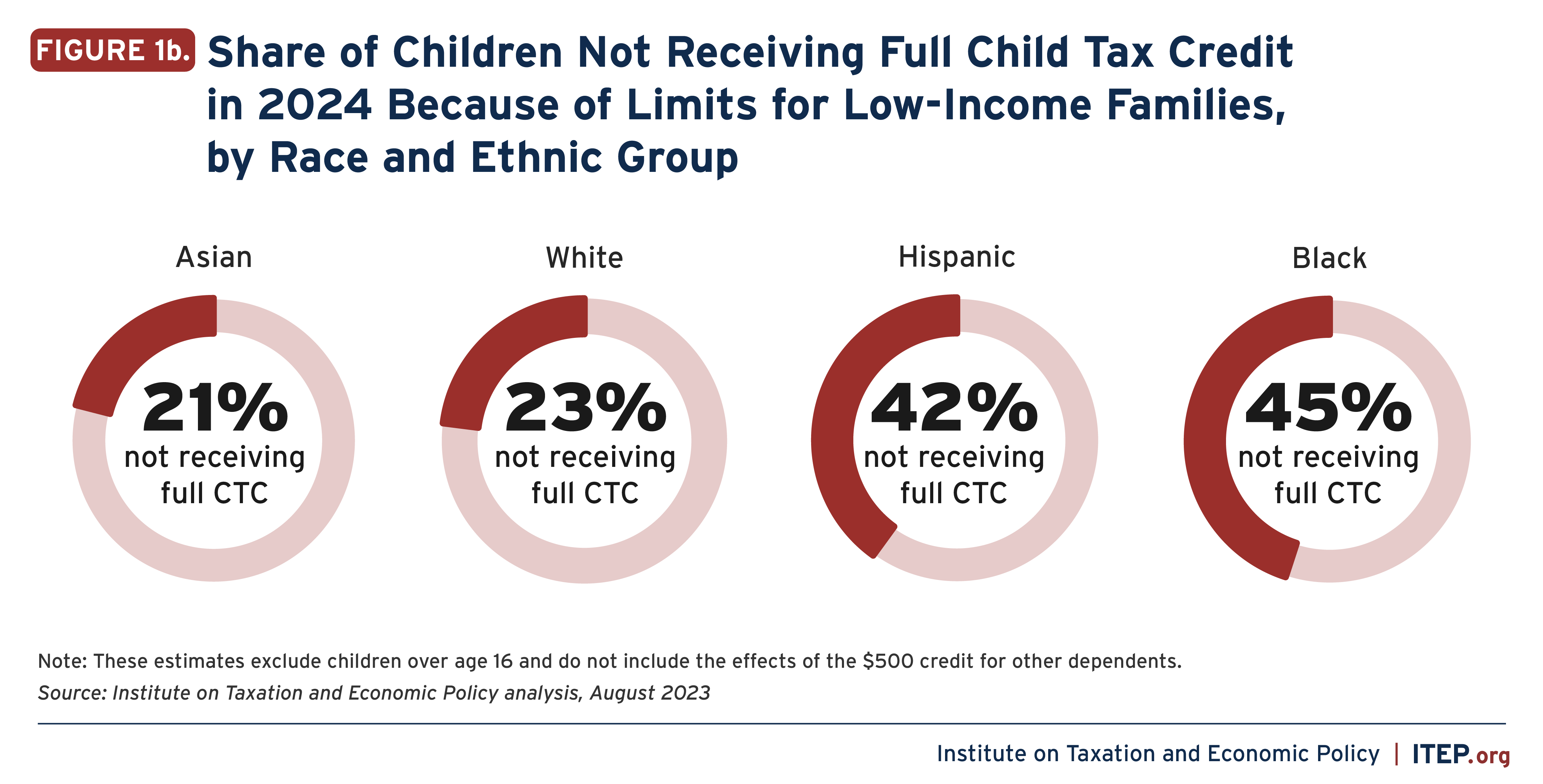

• Black and Hispanic families are disproportionately harmed by current rules preventing low-income people from receiving the full federal Child Tax Credit. Next year, 45 percent of Black children and 42 percent of Hispanic children will not receive the full credit, roughly double the percentages of white and Asian children who are left out.

• If lawmakers reinstated the 2021 credit, no children would be left out because their families’ earnings are too low.

• Black and Hispanic families with kids would receive slightly larger average credits under this expansion since it targets low- and middle-income households and because white children are disproportionately in families whose incomes exceed $150,000 and therefore do not qualify for the full credit. This would partially offset existing inequities in the tax code and help shrink the racial wealth gap.

The federal Child Tax Credit (CTC) is one of the most effective tools that the U.S. uses to assist families with children, raise incomes, and reduce poverty. The CTC provides families with a tax credit of up to $2,000 for each child in their household. The credit is only partially refundable, though, with limits that prevent families with lower income from receiving the full credit. Often the poorest families get no credit at all. This means that a policy meant to help children does less for poor children of all races and disproportionately leaves out Black and Hispanic children.

ITEP previously estimated that Congressional Democrats’ proposal to expand the Child Tax Credit would help nearly 60 million children next year, especially those in lower-income families. This analysis expands on that work by estimating how the proposal would affect Americans in different racial and ethnic groups. Expanding the federal Child Tax Credit to 2021 levels would help children of all races and would be particularly beneficial to children and families of color, helping to mitigate existing inequities in the tax code that contribute to the racial wealth gap.

The credit was temporarily expanded in 2021 as part of the Biden administration’s COVID response plan. That expansion increased the credit amount and made it available to all children, including those in families with very little income. The expansion was enormously successful, cutting child poverty nearly in half. And despite warnings from skeptics, the credit expansion did not prevent low-income parents from re-entering the workforce.

Using evidence of the temporary expansion’s success, many lawmakers now want to make the enhanced credit a permanent feature of the tax code. President Biden included an expansion of the Child Tax Credit in his annual budget request earlier this year, and more recently, Democrats in the House and Senate have introduced bills with the support of nearly the entire Democratic caucuses. This analysis models the House’s American Family Act.

Three Proposals Would Increase the Credit and Make it Fully Available to the Poorest Children

The President, House, and Senate proposals all largely mirror the temporary 2021 expansion, with a few differences. All three proposals:

- Increase the credit for all children in low- and middle-income families, with larger increases for children under 6.

- Remove limits on the refundable portion of the credit to ensure the credit is fully available to all children in low- and middle-income families. (See our earlier piece for a more detailed explanation of the House CTC proposal and current limitations on refundability.)

- Allow parents to claim the CTC for children up through age 17 rather than 16.

- Make the credit available to parents monthly rather than as a once-a-year lump sum to help match the credit with a household’s normal bills and other expenses.

In addition, the House proposal would:

- Adjust the credit annually for inflation.

- Restore the inclusion of children with Individual Tax Identification Numbers (ITINs), reversing a change made by 2017’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.[1]

- Provide a larger credit in the first month of a child’s life to ensure that all families have enhanced resource access during the critical time immediately following the birth of a child.[2]

Families of Color Would Benefit Most from Child Tax Credit Expansion

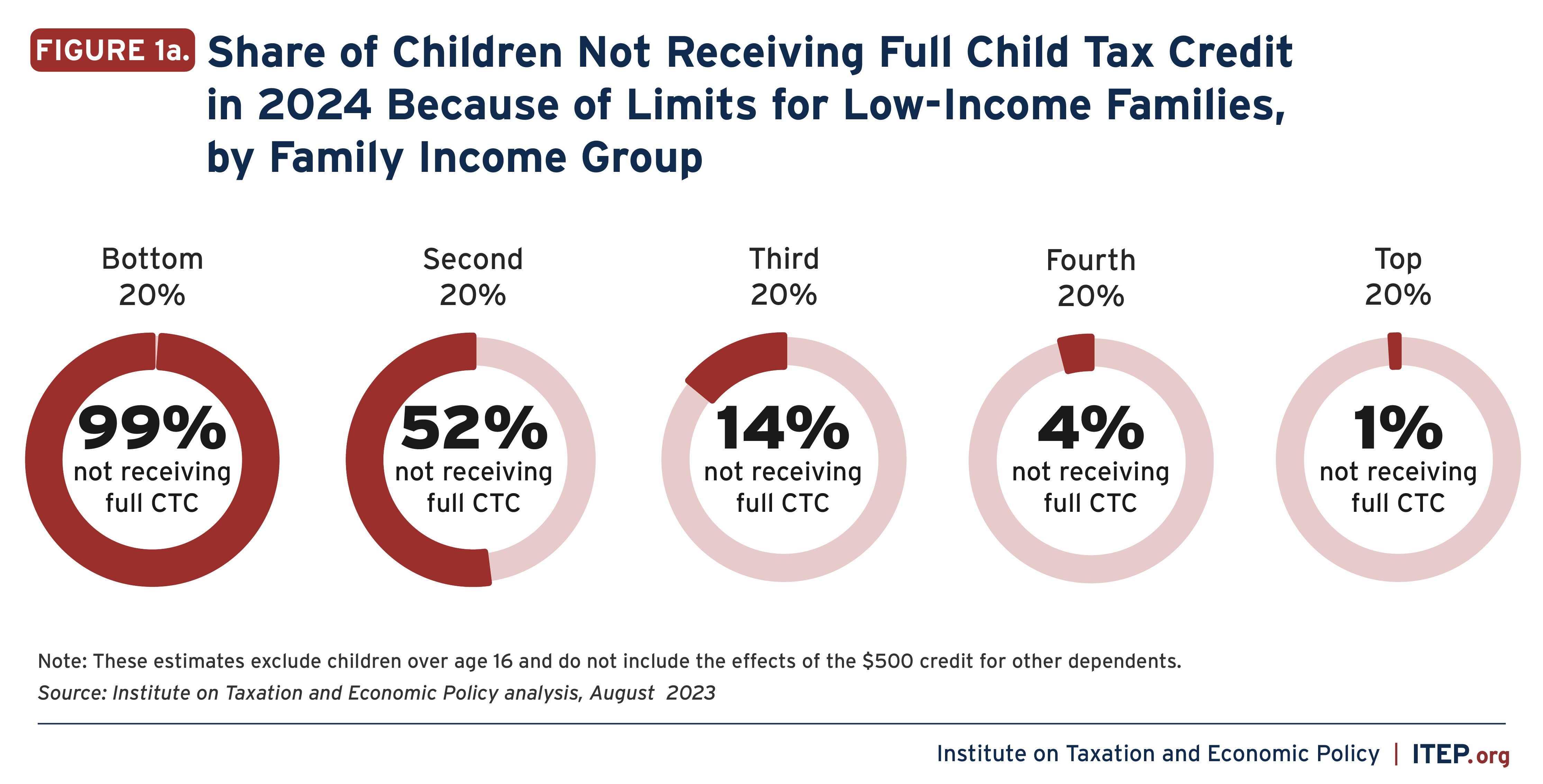

Current Child Tax Credit rules create an illogical system where a credit designed to help children is reduced or entirely unavailable to the children who would most benefit from it. This includes children raised by grandparents, parents with disabilities, or parents working as full-time caregivers. Next year, three-quarters of all children whose families are in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution (annual earnings of less than $51,000) will receive a reduced credit or no credit at all due to these limits. And nearly every child in the bottom 20 percent (whose families make less than $25,000) will receive a reduced credit or no credit.

Children of all races are harmed by these limits, especially Black and Hispanic children. Next year, 45 percent of Black children and 42 percent of Hispanic children will not receive the full credit, roughly double the percentages of white and Asian children who are left out. Under the House proposal, no children would be left out because their families’ earnings are too low.

All families pay taxes. Everyone who works – even for very low wages – pays federal payroll taxes. Most people who own or rent a home pay property taxes, and people who buy goods or services pay sales taxes. But the federal personal income tax is designed to be a progressive tax which partly offsets the other more regressive taxes that people pay. After factoring in deductions and credits, many low-income families owe very little or nothing in federal income taxes. An income tax credit is only useful to these families if it is refundable, meaning it can be received as a tax refund exceeding the federal income tax they owe.

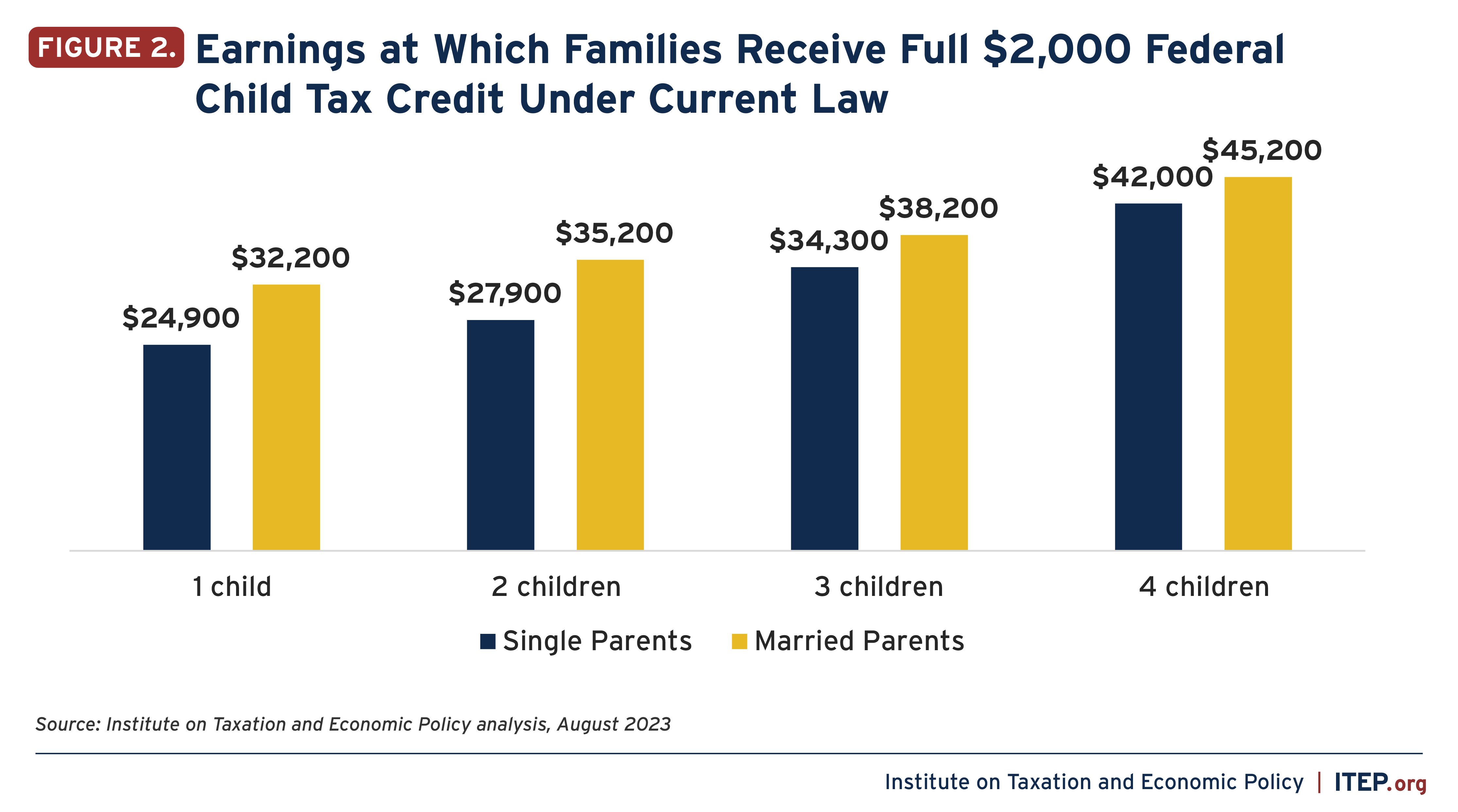

There are currently two limits on the refundable portion of the CTC which limit its utility to low-income families. First, the refundable portion is less than the full credit amount. Second, the credit is phased in with a family’s earnings above $2,500, limiting the credit amount even further for low-income families. Next year, a single-parent household with two children will need at least $27,900 in earnings to receive the full credit under current law.

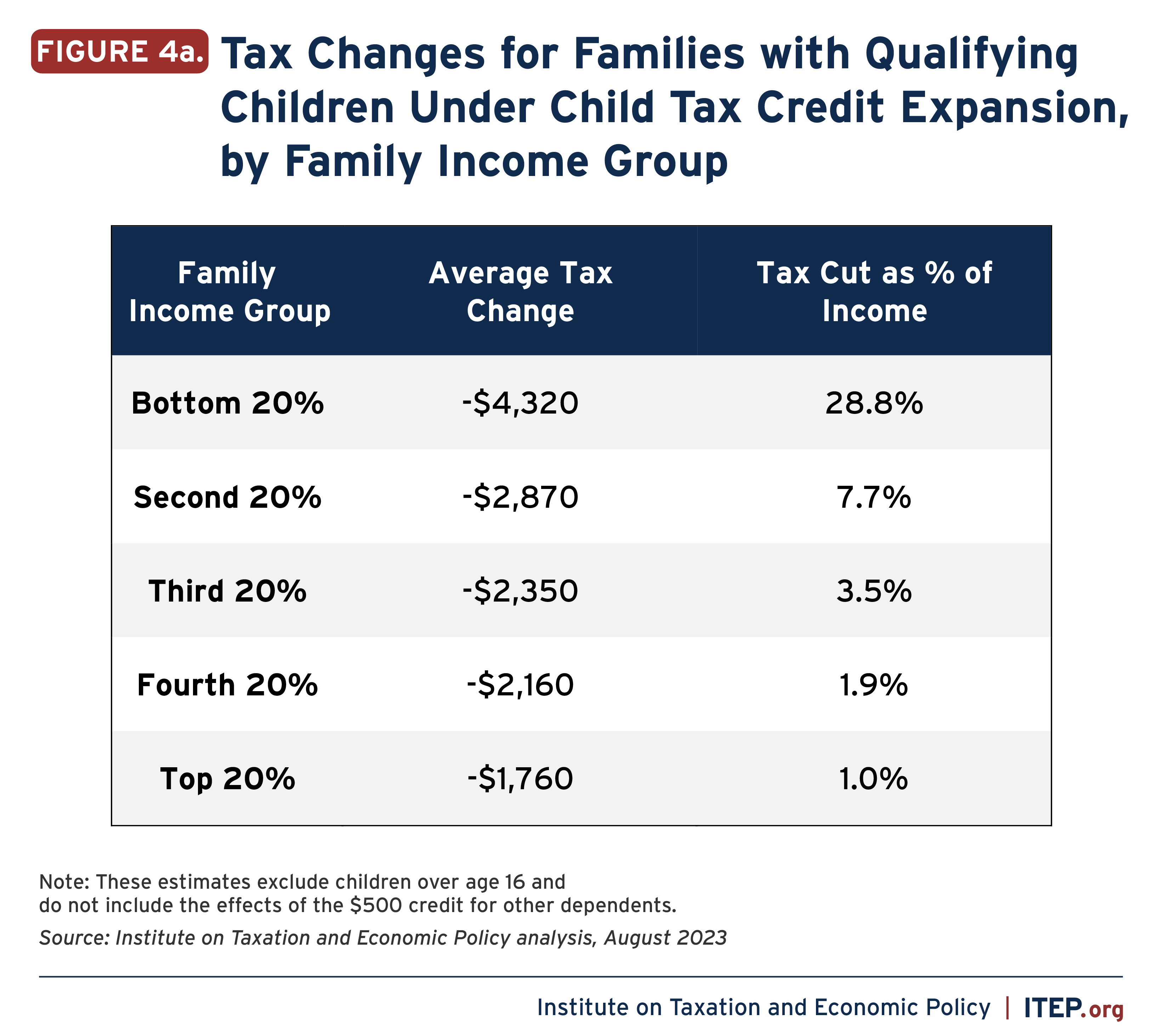

Removing the refundability limitations would make the expanded credit larger for families with less income. Next year, families with qualifying children in the bottom 20 percent would see an average tax reduction of more than $4,000 under the House bill. Families in the top 20 percent would benefit from the expanded credit amount while being mostly unaffected by the changes to refundability, so would see an average tax reduction of $1,760.

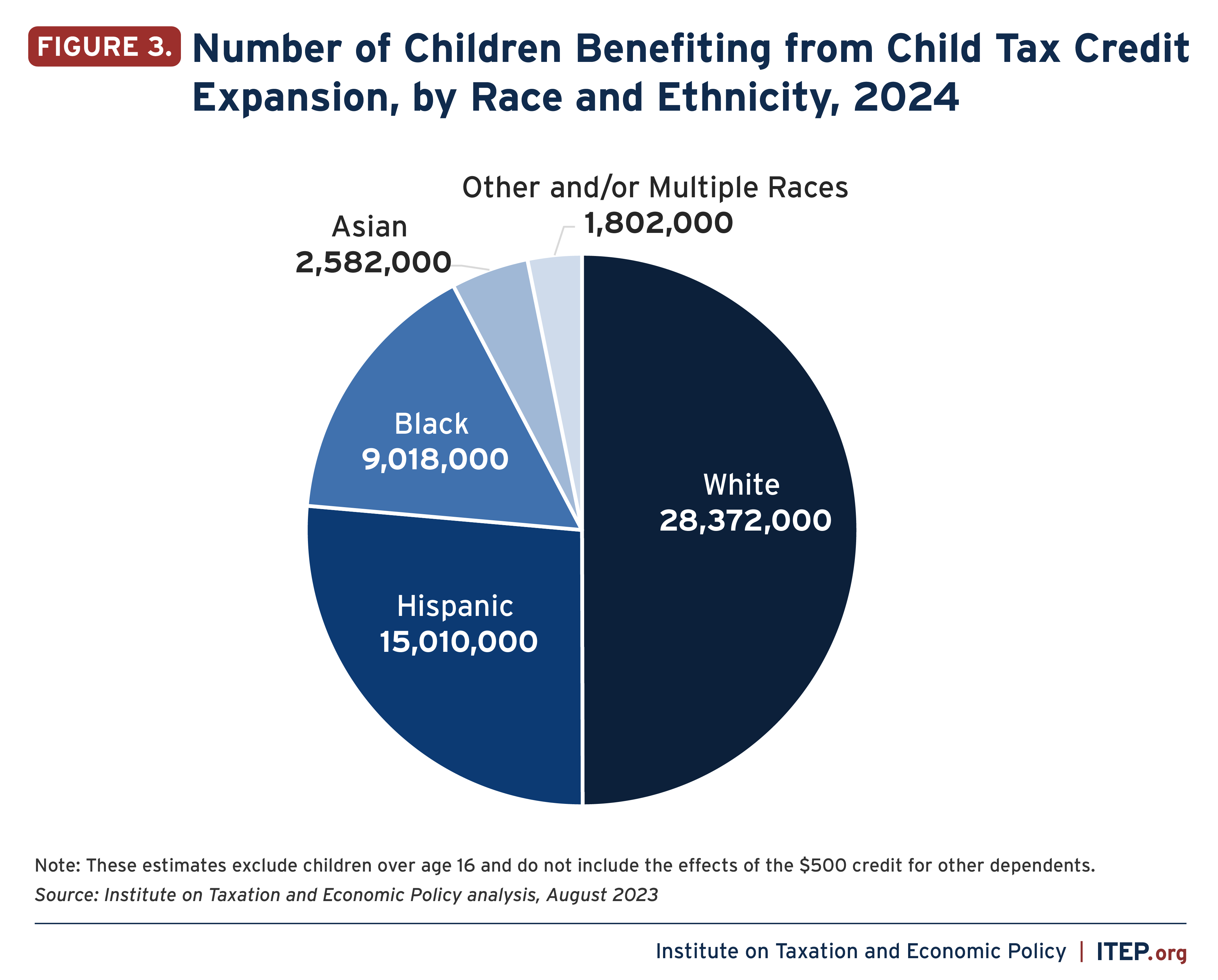

These changes would help nearly all children in low- to middle-income families. White children would make up the largest group of beneficiaries from the proposal (50 percent) but Black and Hispanic children would benefit disproportionately because they are disproportionately harmed by the limits on the credit under current law due to lower average family income.

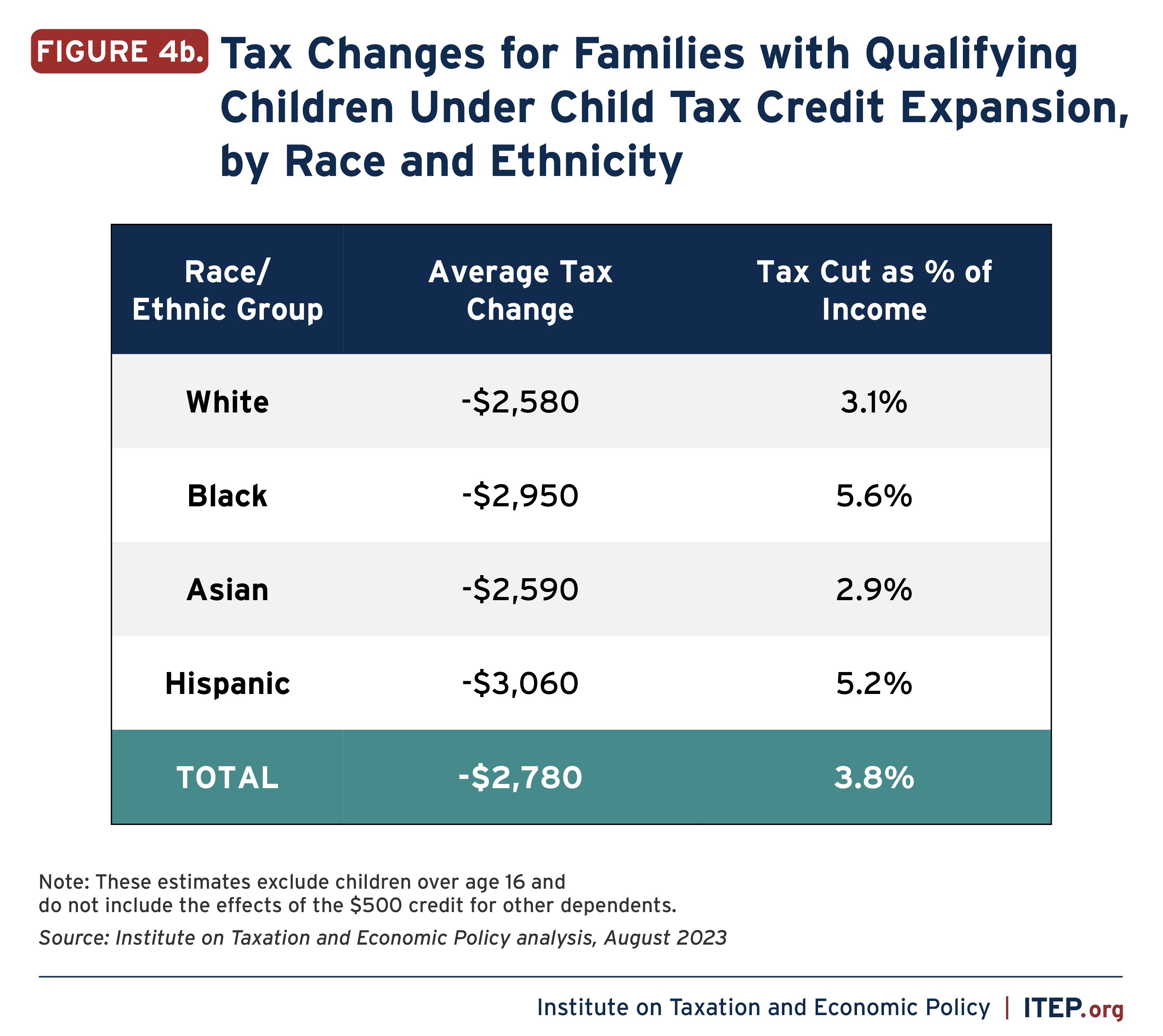

Since current limits for lower-income families disproportionately leave out children of color, removing the limits would disproportionately help these groups. We estimate that the average tax reductions for Black and Hispanic families with children eligible for the credit would exceed the average tax changes for white and Asian families.

Next year, if these changes were made, Black families with qualifying children would receive an average tax cut of nearly $3,000. White families with children would receive an average tax cut of $2,580. The credit increase would roughly equal a 5.6 percent income boost for Black families with children and a 5.2 percent boost for Hispanic families with children.

Boosting the Child Tax Credit Would Help Reorient the Tax Code

The typical white family has eight times as much wealth as the typical Black family and five times as much as the typical Hispanic family, according to the Federal Reserve. (The Fed does not provide data beyond these three groups.) The tax code has contributed to these gaps by treating income from wealth more generously than income from work.

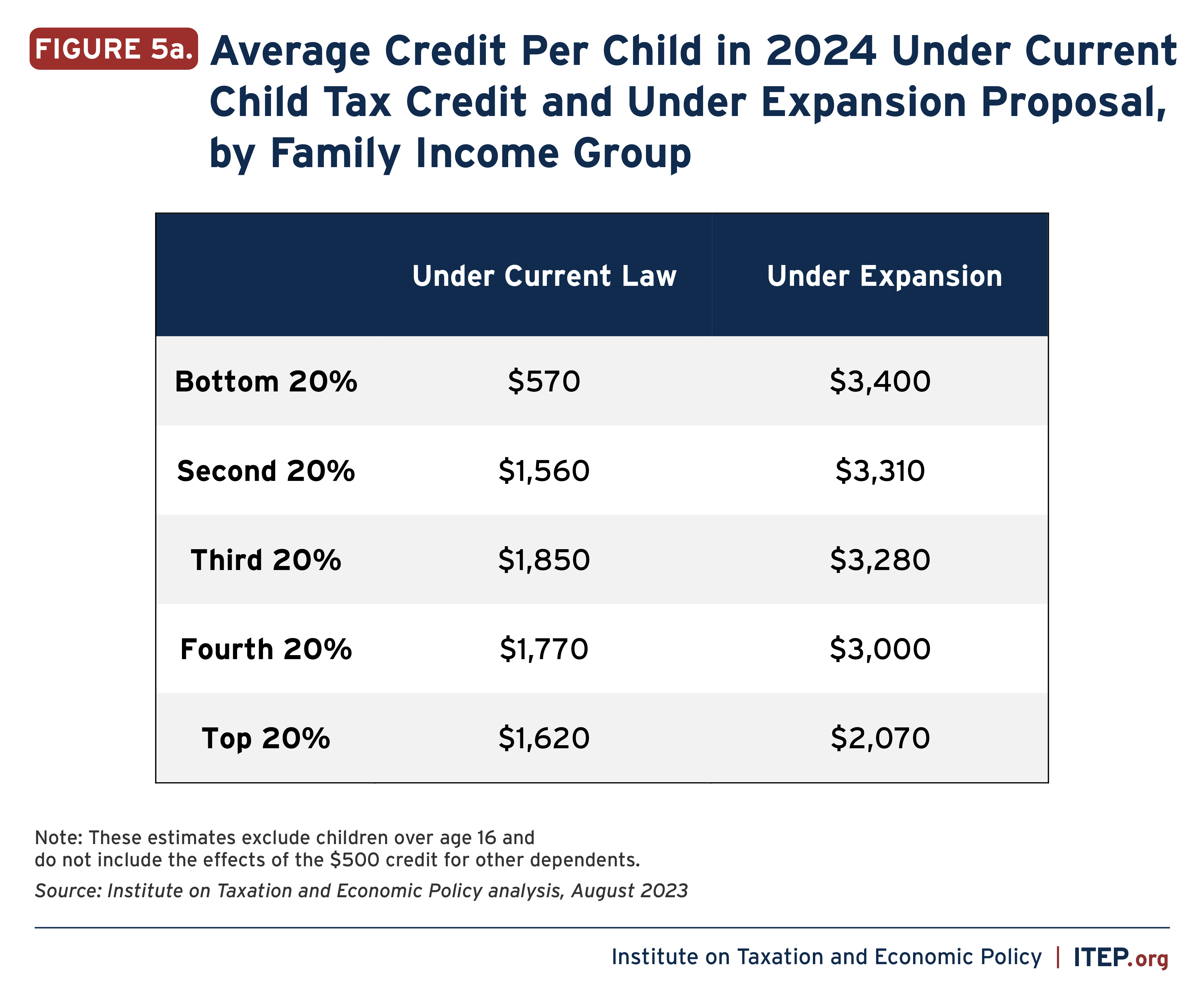

While expanding the CTC would not directly address the policies that benefit wealth concentration, it would likely modestly shrink wealth gaps by reorienting the tax code toward helping low- and middle-income families. Under current law, children in poorer families receive a much smaller CTC on average than children in higher-income families. The average credit per child for the bottom 20 percent will be just $570 next year, about $1,000 less than for any other income group. The House proposal would increase the size of the credit for families in every income category. At the same time, it would reverse the current imbalance that provides more to children in higher-income families and instead provide a greater average credit to children in the lowest-income groups.

Likewise, we estimate that Black and Hispanic children currently receive slightly smaller credits than white children. If this proposal were in effect next year, however, Black and Hispanic children would receive larger credits on average since the expansion targets families in the bottom 80 percent of income earners and white families are more likely to be in the top 20 percent.

Most families with children, regardless of race, will receive a larger tax credit under the revised proposal than under current law. And families at the same income level with the same number of children will receive the same size credit. The expanded credit is targeted to families earning less than $150,000 which includes most families of all races. But white families are overrepresented, and Black and Hispanic families are under-represented in those upper-income families, who have less need for income support. The revised credit would help these wealthy families to the same degree as current law but would target more resources to families of all races who earn less than $150,000 and who have greater need for a tax credit that helps children thrive economically.

The most significant tax policy contributor to the wealth gap has been favorable treatment of income from wealth (like capital gains and dividends) over income from work. If a family earns their living through jobs that provide salary and wages, they are taxed on every paycheck up to 37 percent. On the other hand, people who live off their income through the appreciation of assets like stocks and bonds do not always owe taxes as their wealth accrues, and when they do, they are often taxed at a lower rate. The Treasury Department has estimated that the benefit of the lower capital gains rate goes almost entirely to white families.

ITEP previously found that the growth of the racial wealth gap in recent decades is driven by the concentration of stocks and bonds among white families. The racial wealth gap grew slightly between 1990 and 2022, but when corporate equities are excluded from wealth, the gap shrunk. These corporate equities generate much of the capital gains and dividends that are taxed at lower rates than other types of income that low- and middle-income people and people of color are more likely to earn, like wages. The income generated by the corporations often escapes the corporate income tax as well.

Similarly, the average white family owns a larger value in real estate than the average Black or Hispanic family. For families of color, real estate holdings— particularly their principal residence—typically represent the largest source of their net worth. White families who benefited from racially discriminatory policies like redlining and therefore enjoy higher appreciation of their real estate holdings can now benefit from tax breaks they receive upon selling a home. Likewise, white families receive a much higher share of the benefit of the mortgage interest deduction relative to their proportion of the population.

While Congress should also change how the tax code rewards wealth over work, expanding the Child Tax Credit and making it fully available to the lowest income children would be a big step towards a fairer tax code and more equitable society. Unfortunately, these proposals stand in contrast to other bills proposed in the House that would mostly help the very wealthy and likely worsen the racial wealth gap. Our nation’s laws should work for the many not the few and should particularly help those most in need.

Notes

[1] This analysis does not include the effects of ITIN inclusion. Including the change would increase the impact of this proposal. There are significant data limitations to estimating the population that would be affected by this change, but the Center for Migration Studies estimates upwards of 1.1 million children in the United States lacking Social Security Numbers (SSN). ITEP has previously estimated the number of children in households where at least one member lacks an SSN is likely much greater.

[2] This analysis does not include the effects of the increased credit for newborns. Including the change would increase the impact of this proposal.

3. This analysis looks at the four largest single race/ethnicity groups in the United States. Due to data constraints, we are limited in what we can say about smaller groups, such as indigenous peoples, but recognize that there are impacts on families that identify with racial categories outside of the four discussed in this report

4. Throughout this report, we use the term ‘families’ or ‘households’ for ease when referring to tax units. A tax unit is made up of an individual or married couple that files a tax return, and any dependents that they claim.

5. ITEP uses the self-reported race or ethnicity of the head of a tax unit when ascribing race or ethnicity to a tax unit. Where this report refers to the race or ethnicity of children, it is therefore referring to children living in tax units headed by an individual of that race or ethnicity.