EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In its rush to pass a major rewrite of the tax code before year’s end, Congress appears likely to enact a “tax reform” that creates, or expands, a significant number of tax loopholes.[1] One such loophole would reward some of the nation’s wealthiest individuals with a strategy for padding their own bank accounts by “donating” to support private K-12 schools. While a similar loophole exists under current law, its size and scope would be dramatically expanded by the legislation working its way through Congress.[2]

This report details how, as an indirect result of capping the deduction for state income taxes paid, the bill expected to emerge from the House-Senate Conference Committee would enlarge a loophole being abused by taxpayers who steer money into private K-12 school voucher funds. This loophole is available in 10 states: Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Kansas, Montana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia.

The report’s findings include:

- The number of households able to turn a profit by making so-called “donations” to private school voucher funds (or “scholarship granting organizations”) would increase significantly—and for the first time would include most of the wealthiest families living in states that offer voucher tax credits. Looking just at the top 1 percent of earners, the number of taxpayers potentially eligible to use this shelter would at least double, from roughly 36 to 82 percent of this elite group.

- Compared to the current loophole, the profits that could be generated by “donating” would grow in most states. In Arizona and South Carolina in particular, some extremely high-income donors who are currently unable to profit could suddenly begin collecting yearly profits measured in the millions of dollars, per household. Risk-free profit margins on cash donations would rise as high as 37 percent of the amount donated in Arizona, Georgia, Montana, and South Carolina.

- High-income investors who donate stock, rather than cash, in South Carolina and Virginia would see larger profits than any other group because of this lucrative shelter. Investors in these states would enjoy four or five separate tax benefits in return for “donating” corporate stock to fund private school vouchers. Many investors using this shelter would, for the first time, receive higher returns on their stock donations after taxes than before. This report details one example scenario in which a South Carolina investor with $75,000 in pre-tax capital gains income could walk away with a nearly $121,000 gain, after taxes, because of the expanded tax shelter expected to be made available under the Conference Committee’s bill.

- As a result of this federal legislation, private schools in five states (Alabama, Kansas, Montana, Oklahoma, and Virginia) could expect a $50 million windfall next year as more high-income taxpayers rush to claim the profits available under this expanded loophole. Notably, these first-time donors are much more likely to be opportunistic tax-avoiders than dedicated private school proponents. Taxpayers who sincerely care about private school education are likely already donating in these states, given the substantial state-level incentives currently offered in return for such gifts.

- Increased funding for private school vouchers, and larger profits for opportunistic “donors,” would come at a cost to state budgets and the public services they fund. State revenues could quickly decline by $40 million or more because of increased payouts to support private school vouchers in the wake of these federal tax changes.

- The impact of this loophole would likely grow in the years ahead. High-income taxpayers interested in turning a profit for themselves would consistently flock to state private school tax credits because of these new federal laws. As a result, every dollar made available under state-level credit programs is likely to be claimed in full each year, and state lawmakers may be tempted to expand those programs to keep up with demand. Meanwhile, that apparent “success” of these credits in encouraging donations may lead lawmakers in other states to consider enacting similar credits.

INTRODUCTION TO VOUCHER TAX CREDITS

Voucher tax credits—also known as tuition tax credits, scholarship tax credits, or neovouchers—offer a lucrative incentive designed to spur taxpayers to donate to nonprofit organizations that distribute K-12 private school vouchers. These nonprofit organizations are often referred to as “scholarship granting organizations,” or SGOs. In eighteen states, donors are rewarded with state tax credits that wipe out 50 percent, or more, of the cost of donating to these organizations. In eight of these states, the tax credits are equal to 100 percent of the amount donated, meaning that every dollar “donated” is reimbursed with a dollar in state tax cuts. So-called “donors” receiving these 100 percent credits make no personal financial sacrifice because their gifts are fully offset with a dollar-for-dollar state tax cut.

These types of tax credits are very different from most charitable giving tax incentives, which take the form of a deduction, not a credit. A charitable tax deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income, meaning that no tax is owed on the amount of income that was given away. Unlike tax credits, the value of a tax deduction depends on the taxpayer’s tax bracket. Deducting $1,000 of income to avoid a 5 percent state income tax, for example, will save a taxpayer $50. Deducting that same amount to avoid a 37 percent federal income tax rate will save that taxpayer $370. But claiming a 100 percent tax credit of $1,000 will save that taxpayer a full $1,000.

The loophole explained in this report hinges on claiming multiple tax benefits—including both credits and deductions—on the same donation, thereby triggering an overall tax cut larger than the amount originally donated. The result is a financial profit for the “donor,” a far cry from the ordinary meaning of the word “charity.”

THE LOOPHOLE

Tax loopholes are rarely straightforward, and this one is no exception. Previous ITEP reports offer a detailed analysis of the loophole that exists in current law. Ironically, the current loophole is mostly limited to taxpayers falling under the federal Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT)—a backstop tax meant to ensure that even taxpayers enjoying many tax breaks still pay some minimum amount of federal income tax.[3]

On its face, the change in law that would expand this loophole has nothing to do with either charitable giving or private school education. But separate components of the tax code can interact with each other in unusual ways. And by capping one tax deduction (the write-off for state income tax payments), Congress is all but guaranteeing that that there will be a surge of abuse in an entirely different deduction (the write-off for taxpayers’ charitable gifts).

On its face, the change in law that would expand this loophole has nothing to do with either charitable giving or private school education. But separate components of the tax code can interact with each other in unusual ways. And by capping one tax deduction (the write-off for state income tax payments), Congress is all but guaranteeing that that there will be a surge of abuse in an entirely different deduction (the write-off for taxpayers’ charitable gifts).

Under the Conference bill, many high-income taxpayers would no longer see their federal taxes rise if their state tax bill declines, because they would continue deducting the maximum $10,000 allowed.[4] Meanwhile, most high-income taxpayers would still be able to deduct their charitable contributions in full. As a result, many taxpayers would find that, for the first time, making donations that qualify for state voucher tax credits would be highly profitable.

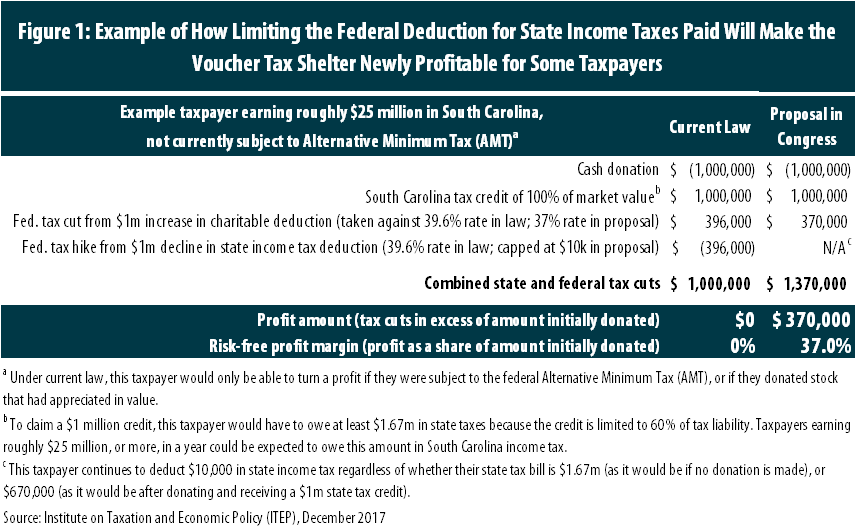

Figure 1 explains how this works, using the example of a South Carolina millionaire. In South Carolina, taxpayers can “donate” as much as they would like to support private school vouchers, and then receive state tax credits in return that offset the entire cost of donating.[5] Under current law, this taxpayer sees no change in their federal tax bill because while making a donation increases their federal deductions for charitable giving, they also lose an equivalent amount of federal deductions for state income taxes paid (because the South Carolina tax credits have reduced their state income tax payments).[6] Under the proposal in Congress, by contrast, the taxpayer is not allowed to deduct their state income tax payments above the $10,000 cap anyway, so their state income tax deduction does not change as a result of claiming a voucher tax credit.

In short, somebody affluent enough to “donate” $1 million in South Carolina receives not just $1 million in state tax credits in exchange for their “generosity,” but also a federal charitable deduction worth nearly $400,000.[7] Under the current system, a $396,000 charitable deduction gain is offset by a $396,000 loss in the deduction for state income taxes paid. So the net result is $1 million in tax cuts as payment for a $1 million donation.

But under the new system, with little state income tax deduction left to lose, the net result is very different: $1.37 million in tax cuts in exchange for a donation of just $1 million. This risk-free, one-year profit margin of 37 percent far exceeds the kind of return that could be expected from almost any other investment.

WHO PROFITS?

Under current law, taxpayers subject to the federal Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) are the group most likely to be able to profit from use of the voucher tax shelter.[8] Taxpayers paying AMT are overwhelmingly high-income, though not necessarily the very richest. In 2015, 70 percent of AMT payments were made by taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $1 million, and 57 percent of taxpayers in this group owed some amount of AMT. Another 23 percent of AMT revenue came from taxpayers earning over $1 million per year, with 19 percent of taxpayers in this group owing some amount of AMT.[9]

Under the tax system likely to emerge from the Conference Committee, the voucher tax shelter would work quite differently than it does today. Although AMT-payers would still be able to use this shelter, owing AMT would no longer be necessary to reaping a profit.[10] Instead, a significant number of taxpayers subject to ordinary income tax rules would suddenly find the shelter profitable.

To profit, a taxpayer needs to be in a situation where an additional dollar in charitable deduction can reduce their federal tax bill, but a dollar in reduced state income tax payments does not raise their tax bill.

The group most likely to fit this description are extremely high-income taxpayers paying significantly more than $10,000 in state income tax per year. For this group, a dollar in state tax credit is unlikely to move them below the $10,000 cap on deductible taxes, and thus will not change their federal tax bill. But a dollar in additional charitable donations will reduce their federal taxes.

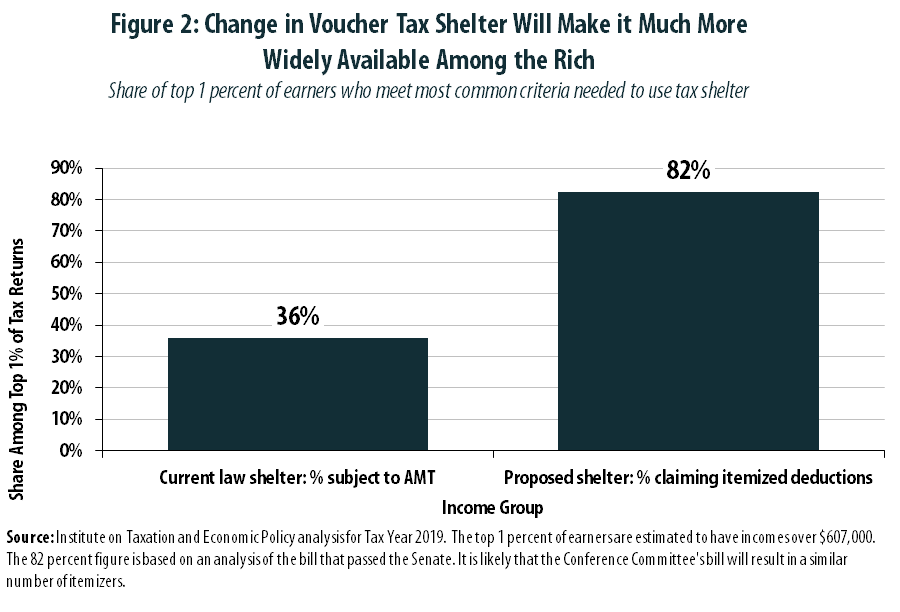

As seen in Figure 2, most of the richest people in the country are likely to itemize under the type of system being debated by Congress, meaning the first dollar deducted in charitable donations will result in a federal tax savings. But even some taxpayers initially inclined to use the standard deduction could profit on the portion of their donation that causes their total itemized deductions to exceed their standard deduction.[11] And investors donating stock or property, rather than cash, can also come out ahead regardless of whether they happen to itemize.[12]

Looking just at the top 1 percent of earners, the share able to take advantage of the voucher tax shelter will at least double under the bill being considered by the Conference Committee. While a little more than one-third (36 percent) of this group pays AMT under current law, more than four-fifths (82 percent) can be expected to claim itemized deductions under the new system and thus will have the charitable deduction readily available to them.

MEASURING PROFITS ON ORDINARY DONATIONS

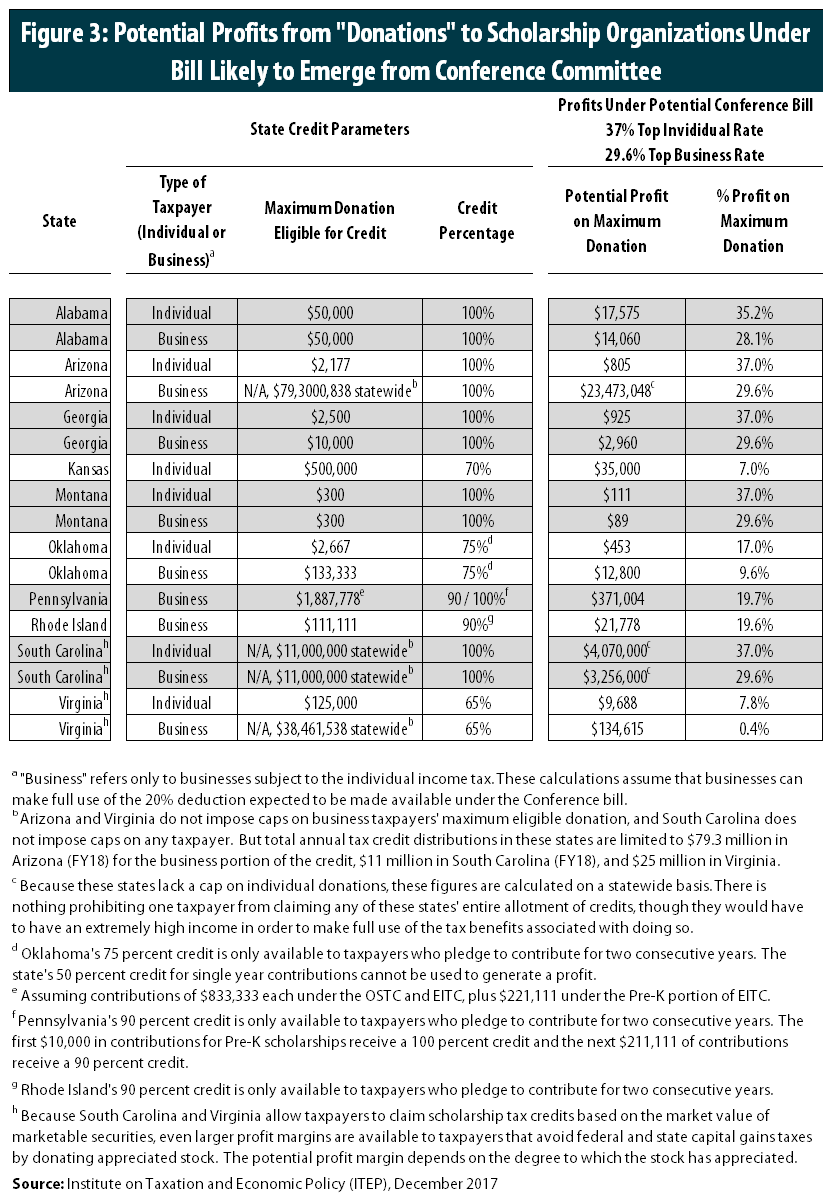

Figure 3 reports the potential profits that could be reaped by private school donors making monetary, or “cash,” donations in 10 states in the wake of Congress capping the deduction for state income taxes paid. A 2016 ITEP report contains similar calculations of the shelter’s profitability under current law.[13]

Profit margins would increase in most states, reaching a high of 37 percent of the amount donated in Arizona, Georgia, Montana, and South Carolina. This is because the federal tax deductions received in return for these donations will become more valuable.[14]

Moreover, extremely high-income taxpayers in South Carolina, as well as highly profitable pass-through businesses in Arizona, will find dramatically higher profits to be possible under this new system. This is because while the current shelter is mostly used to reduce only the portion of tax liability attributable to the AMT, the expanded shelter can reduce the taxpayer’s overall federal income tax bill.

MEASURING PROFITS FOR INVESTORS

In most states with voucher tax credits, taxpayers can only receive the credits in exchange for monetary, or “cash,” donations—not donations of stock or property. In South Carolina and Virginia, however, taxpayers can donate stock and receive tax credits equal to its market value at the time of the donation. This provision allows for even more lucrative uses of the voucher tax shelter because it permits taxpayers to claim four or five different tax benefits on the same donation:

- State voucher tax credit

- State charitable deduction (Virginia only)

- Federal charitable deduction

- Avoidance of state tax on capital gain

- Avoidance of federal tax on capital gain

A separate ITEP article discusses this shelter in detail and concludes that:

In South Carolina and Virginia, lawmakers eager to shift public dollars to private schools have devised tax credits so generous that investors are often better off giving their stock away to fund private school vouchers than they are selling it to an ordinary buyer.[15]

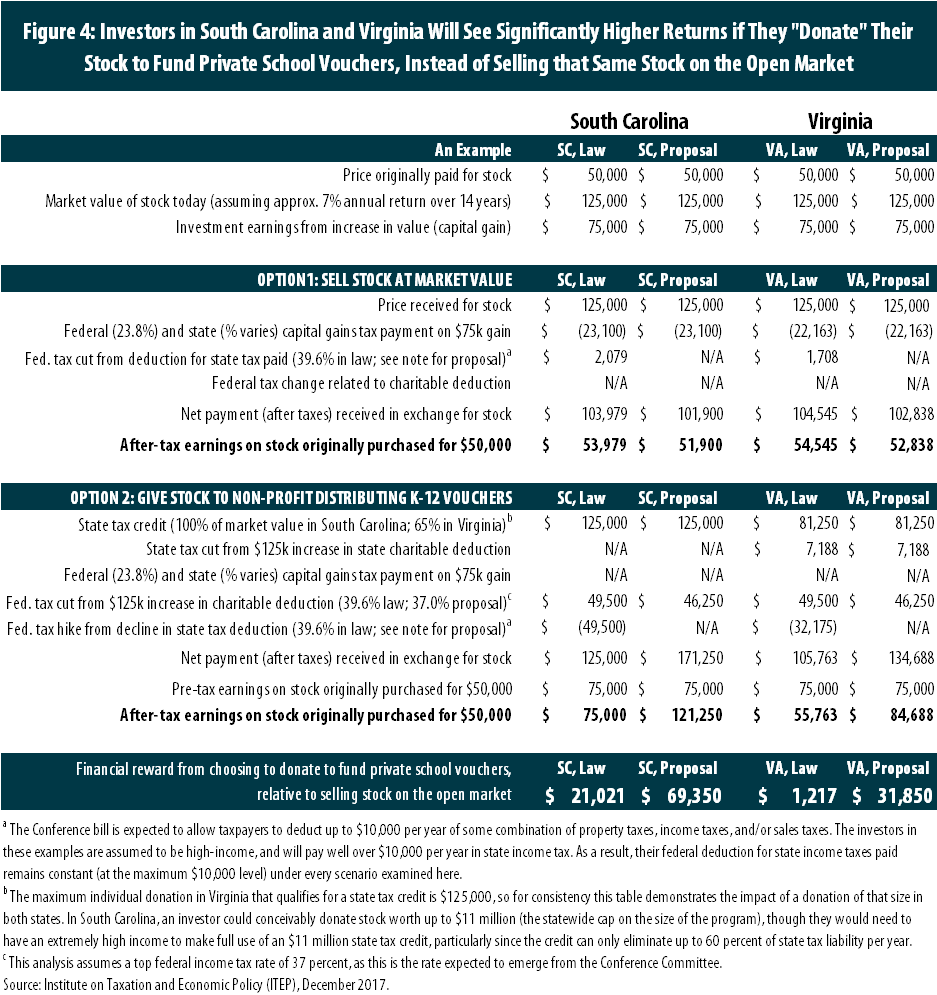

Figure 4 shows how this shelter would be expanded under the legislation making its way through Congress, because investors would no longer receive a state income tax deduction that would be reduced as a result of participating in this shelter. Many wealthy investors in these two states would, for the first time, see a higher level of earnings after taxes than before. In South Carolina, for instance, Figure 4 shows an actual gain of $75,000 in market value becoming a $121,250 gain after generous tax rewards are factored into the calculation. In Virginia, an identical pre-tax gain of $75,000 swells to a post-tax gain of $84,688 via the shelter.

Just as worrisome is that an investor in either of these scenarios would be much better off from “donating” that stock to fund private school vouchers instead of selling it on the open market in an ordinary transaction. In this scenario, the taxpayer’s decision to “donate” puts them ahead by $69,350 in South Carolina or $31,850 in Virginia. This outcome is both distortionary and unfair, as it essentially forces savvy investors seeking out the highest returns to participate in the funding of private K-12 school vouchers.

SHORT-RUN CONSEQUENCES FOR PRIVATE SCHOOL FUNDING AND STATE TAX REVENUES

In the short-run, the impacts of this expanded federal tax loophole will be felt most acutely in states such as Alabama, Kansas, Montana, Oklahoma, and Virginia. Taxpayers in these states have shown only limited enthusiasm for existing voucher tax credits, and the expanded federal loophole could very quickly change that fact. Alabama, for instance, allows $30 million in state tax credit payouts each year, but as much as $10 or $20 million of that amount has gone unclaimed as of late.[16] Meanwhile Kansas had $9.5 million in unused tax credits last year, while Montana had roughly $2 million, Oklahoma had about $2.5 million, and Virginia had approximately $15 million.[17]

Under the revised tax system being debated by Congress, a larger and wealthier pool of taxpayers will be able to use these credits as part of a profitable voucher tax shelter. It is therefore likely that these states will see a dramatic uptick in donations to private K-12 voucher funds. But those taxpayers who choose to begin donating because of an expanded tax shelter are unlikely to care much about private schools. Donors who care about these organizations already have ample opportunities to donate today. Instead, the new “donors” lured into the program by an expanded shelter will be primarily pursuing their own self-interest.

Under the revised tax system being debated by Congress, a larger and wealthier pool of taxpayers will be able to use these credits as part of a profitable voucher tax shelter. It is therefore likely that these states will see a dramatic uptick in donations to private K-12 voucher funds. But those taxpayers who choose to begin donating because of an expanded tax shelter are unlikely to care much about private schools. Donors who care about these organizations already have ample opportunities to donate today. Instead, the new “donors” lured into the program by an expanded shelter will be primarily pursuing their own self-interest.

Across these fives states, public revenues could be expected to decline by roughly $40 million per year if taxpayers seeking a profit for themselves begin making full use of these states’ credits following the expansion of the voucher tax shelter.[18] In this case, a loss of public revenues is a gain for private schools: credit claims of this size would indicate an increase in private school funding upwards of $50 million per year.[19]

In the other states discussed in this report—Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Carolina—it is unlikely that there will be a meaningful change in state revenues or private school funding because of the change in this tax shelter. This is because these states already routinely pay out every dollar of available tax credit each year, sometimes within hours of those credits being offered to taxpayers.[20]

But while the overall amount donated in these states may not change, the types of donors participating might. By expanding the shelter outside of the AMT and into the ordinary federal income tax, extremely high-income donors are more likely to begin participating, and reaping substantial profits in return. In South Carolina, for instance, it is not difficult to imagine the state’s entire allotment of tax credits being claimed by a very small number of extremely wealthy donors.[21]

But while the overall amount donated in these states may not change, the types of donors participating might. By expanding the shelter outside of the AMT and into the ordinary federal income tax, extremely high-income donors are more likely to begin participating, and reaping substantial profits in return. In South Carolina, for instance, it is not difficult to imagine the state’s entire allotment of tax credits being claimed by a very small number of extremely wealthy donors.[21]

LONG-RUN IMPLICATIONS FOR STATE VOUCHER TAX CREDITS

If the federal government caps the deduction for state income taxes paid, enthusiasm for state voucher tax credits is likely to surge as the expanded tax shelter they provide becomes favored by high-income taxpayers and their accountants. This high level of interest will surely attract the notice of state lawmakers, and could lead some to consider expanding the programs to keep up with demand. In states such as Georgia and Pennsylvania, for instance, lawmakers have recently attempted to raise their programs’ statewide caps to accommodate taxpayers whose applications were denied due to the programs having already distributed the maximum amount of credits allowed by law.

This surge of interest in state voucher tax credits may also attract attention from lawmakers in other states, and could lead some states to enact these credits in an attempt to replicate the “success” of such highly popular programs.

CLOSING THE LOOPHOLE

Taxpayers who see their “donations” reimbursed by their state governments, with state tax credits, should not be allowed to deduct those so-called “donations” on their federal tax forms. Enacting this reform is vital to ensuring that the charitable deduction is reserved only for genuine charitable gifts where the taxpayer has made a real financial sacrifice.

Moreover, investors who donate stock in return for large tax credits should not be allowed to continue pretending that they have not received compensation in return for their donations. Until this occurs, many investors in South Carolina and Virginia will continue to find that their best financial decision is not to sell their stock on the open market, but rather to give it away to private school voucher organizations in return for lucrative tax subsidies. This is both distortionary and unfair.

Legislation is currently pending in Congress (Rep. Sewell’s H.R.4269) that would accomplish both of these goals.[22]

CONCLUSION

The House-Senate Conference Committee is likely to advance a bill that, as an indirect result of capping the deduction for state income taxes paid, would significantly expand a profitable tax shelter for people who donate to support private K-12 school vouchers and who collect state tax credits in return for those donations. The number of people able to turn a profit under this shelter would increase significantly, as would the potential profit margins, and maximum profit amounts, available in many states.

In the short-run, this change is likely to lead to lower state revenues and higher levels of private school funding in states that are not already paying out every dollar of available credit each year. In the long-run, the increased enthusiasm shown for these types of credits could lead state lawmakers to expand their existing voucher tax credits, or to create new ones entirely.

If Congress decides to cap the deduction for state income taxes paid, that change should include language preventing taxpayers from receiving a federal charitable deduction on the portion of “donations” that have already been reimbursed with state tax credits. This is essential to stopping the voucher tax shelter from being worsened by such a cap.

Moreover, Congress should also prevent taxpayers from using voucher tax credits as a means of dodging taxes on the capital gains income associated with their investments.

Both of these changes are vital to ensuring that the charitable deduction is only claimed on genuine charitable donations in which the taxpayer undertook a financial sacrifice in making their gift.

[1] Faler, Brian. “’Holy crap’: Experts find taxa plan riddled with glitches.” Politico. Dec. 6, 2017. Available at: https://www.politico.com/story/2017/12/06/tax-plan-glitches-mistakes-republicans-208049. Avi-Yonah, Reuven, et al. “The Games They Will Play: Tax Games, Roadblocks, and Glitches Under the New Legislation.” Dec. 7, 2017. Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3084187.

[2] Davis, Carl. “State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Oct. 12, 2016. Available at: https://itep.org/state-tax-subsidies-for-private-k-12-education/. Pudelski, Sasha and Carl Davis. “Public Loss, Private Gain: How School Voucher Tax Shelters Undermine Public Education.” AASA and ITEP. May 17, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/public-loss-private-gain-how-school-voucher-tax-shelters-undermine-public-education/.

[3] See note 2. See also: Davis, Carl. “Private School Voucher Credits Offer a Windfall to Wealthy Investors in Some States.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Aug. 30, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/private-school-voucher-credits-offer-a-windfall-to-wealthy-investors-in-some-states/.

[4] This assumes that high-income taxpayers have state tax liability above $10,000 both before and after claiming a voucher tax credit. As of this writing, it is unclear whether the $10,000 cap will be for a taxpayer’s combined income and property taxes, or whether the taxpayer will be forced to choose between deducting only income taxes, or only property taxes. The conclusions in this report hold under either scenario.

[5] While the tax credits available to any individual or business are not capped, taxpayers cannot use these credits to wipe out more than 60 percent of their state income tax bill. Also, overall statewide tax credit payouts are limited to $11 million per year.

[6] The exceptions are taxpayers subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), and taxpayers donating stock or other property that has appreciated in value.

[7] This deduction value is calculated as a $1 million deduction, taken against a top tax rate of 39.6 percent as proposed by the House. Note that the Senate’s top tax rate would be slightly lower, at 38.5 percent.

[8] An exception is discussed in this article: Davis, Carl. “Private School Voucher Credits Offer a Windfall to Wealthy Investors in Some States.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Aug. 30, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/private-school-voucher-credits-offer-a-windfall-to-wealthy-investors-in-some-states/.

[9] These figures are calculated from IRS Table 1.4, for Tax Year 2015.

[10] The details of the Conference Committee’s AMT proposal have yet to be released as of this writing, but it is likely to be significantly more limited than the current AMT.

[11] A high-income Alabama couple who paid no mortgage interest and gives little to charity, for instance, may only have $10,000 worth of deductible taxes and $1,000 worth of deductible charitable gifts. Since this amount ($11,000) is significantly smaller than the roughly $24,000 standard deduction contained in the House and Senate bills, this couple will not find it beneficial to itemize. But by making a $50,000 “donation” to support K-12 private school vouchers, this taxpayer would find themselves with $61,000 in total itemized deductions. This represents a $37,000 increase in deductions relative to the $24,000 standard deduction they claimed previously, saving them a net of $13,960 if taken against a top federal tax rate of 37 percent. Of course, this taxpayer’s $50,000 donation would also be reimbursed with a state tax credit (assuming the taxpayer has enough state tax liability to make full use of it), meaning that this otherwise non-itemizing taxpayer walks away with $63,960 in state and federal tax cuts in return for a $50,000 donation. For another discussion of this issue, see Manoj, Viswanathan. “How SALT Deduction Repeal Promotes State Capture of Federal Charitable Contributions.” Nov. 9, 2017. Available at: https://surlysubgroup.com/2017/11/09/how-salt-deduction-repeal-promotes-state-capture-of-federal-charitable-contributions/.

[12] Tax benefits for investors are discussed later in this report. But in the case of an investor donating stock who does not itemize, the combined benefit of the state voucher tax credit and capital gains tax avoidance is enough to make the shelter profitable, relative to the taxes that would be owed by selling their stock on the open market.

[13] Davis, Carl. “State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Oct. 12, 2016. Available at: https://itep.org/state-tax-subsidies-for-private-k-12-education/. Note that Kansas appears in this report, but not the 2016 edition, because of a change in state tax law enacted in 2017. Specifically, Kansas’s tax credit was previously restricted to corporations, which are generally not able to profit using this shelter. But Senate Bill 19 of the 2017 legislative session expanded the credit to include individuals as well. For a description, see Kansas Department of Revenue. Notice 17-08. July 1, 2017. Available at: https://www.ksrevenue.org/taxnotices/notice17-08.pdf.

[14] Under current law, the maximum marginal tax rate under the AMT is 35 percent, meaning that no taxpayer subject to AMT saves more than 35 cents in federal tax per dollar donated. Under the bill likely to emerge from the Conference Committee, taxpayers will be able to take their charitable deductions against somewhat higher rates, ranging up to 37 percent. Moreover, profit margins are expected to further increase in Arizona and Georgia because this calculation assumes that these states’ unusual deductions for state income taxes paid will be capped as a result of this provision being caped at the federal level. Under current law, these state-level deductions recapture some of the benefits of the voucher tax credits because the amount of deductible state tax is reduced when a state tax credit is paid out.

[15] Davis, Carl. “Private School Voucher Credits Offer a Windfall to Wealthy Investors in Some States.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Aug. 30, 2017. Available at: https://itep.org/private-school-voucher-credits-offer-a-windfall-to-wealthy-investors-in-some-states/.

[16] Crain, Trisha Powell. “$19 million in tax credits under Alabama Accountability Act still up for grabs.” AL.com. Dec. 2, 2016. Available at: http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2016/12/19_million_in_tax_credits_for.html.

[17] Kansas Department of Education – School Finance Team. “Tax Credit for Low Income Students Scholarship Program.” Legislative Report for January 2017. Available at: http://mediad.publicbroadcasting.net/p/kcur/files/201706/legislative_report_january_2017__tclissp.pdf?_ga=2.241262538.957455917.1496602386-1704001681.1484164029. Hoffman, Matt. “Montanans not lining up for school choice tax credit, even though some could make a buck.” Billings Gazette. Dec. 4, 2017. Available at: http://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/montanans-not-lining-up-for-school-choice-tax-credit-even/article_6d100a76-5f27-55d2-a453-a22c94608c55.html.

[18] This is simply a sum of the unused credit amounts identified above.

[19] The public revenue loss and private school gain figures are not identical because state tax credit percentages vary. For instance, Virginians would have to donate $23.1 million to private schools to receive $15 million in tax credits under the state’s 65 percent tax credit.

[20] Davis, Carl. “State Tax Subsidies for Private K-12 Education.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Oct. 12, 2016. Available at: https://itep.org/state-tax-subsidies-for-private-k-12-education/.

[21] States such as Montana, with lower caps on the amount of tax credit that any individual can receive, will not see this same concentration of tax credit claims among just a small number of donors.

[22] H.R.4269. Public Funds for Public Schools Act. 115th Congress. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4269/text.