President Biden’s most recent budget plan includes proposals that would raise more than $5 trillion from high-income individuals and corporations over a decade.

Like the budget plan he submitted to Congress last year, it would partly reverse the Trump tax cuts for corporations and high-income individuals, clamp down on corporate tax avoidance, and require the wealthiest individuals to pay taxes on their capital gains income just as they are required to for other types of income, among other reforms.

Two significant new proposals in Biden’s budget this year are an increase in the corporate minimum tax that was enacted as part of the Inflation Reduction Act and a provision to improve the existing $1 million cap on corporate tax deductions for compensation.

Of the more than $5 trillion that would be raised by these proposals over a decade, about $1 trillion would go to targeted tax breaks, including expansions of the Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, and health insurance premium tax credits.

This report describes the most significant revenue-raising proposals in the President’s budget.

Key Revenue-Raising Proposals in President Biden’s Fiscal Year 2025 Budget

| Proposal | 10-year revenue impact |

| (Proposals appearing for the first time in this budget plan are highlighted.) | |

| Partly Reversing the Trump Corporate Tax Cuts | |

| Raise Corporate Tax Rate from 21% to 28% | $1.35 trillion |

| Increase the Rate of the IRA’s Corporate Minimum Tax to 21% | $137 billion |

| Preventing Tax Avoidance on Corporate Transfers of Income to Executives and Other Shareholders | |

| Tighten the $1 Million Limit on Deductions for Compensation | $272 billion |

| Increase Stock Buyback Excise Tax from 1% to 4% | $166 billion |

| End Abuses of Tax-Free Spin-Offs | $44 billion |

| Stopping Offshore Corporate Tax Avoidance | |

| Revise Global Minimum Tax Rules and Limit Inversions | $374 billion |

| Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR) | $136 billion |

| Repeal the Deduction for Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) | $158 billion |

| Address ‘Dual Capacity Taxpayer’ Fossil Fuel Companies | $72 billion |

| Bar Earnings Stripping Through Excessive Interest Deductions | $40 billion |

| Strengthening Medicare Taxes on the Rich | |

| Close Loophole in Medicare Taxes for Certain Business Profits | $393 billion |

| Increase Medicare Taxes for the Rich from 3.8% to 5% | $404 billion |

| Limiting Tax Breaks for Capital Gains | |

| Limit Capital Gains Breaks for Millionaires | $289 billion |

| Billionaires’ Minimum Income Tax | $503 billion |

| Limit Like-Kind Exchanges | $20 billion |

| Limiting Tax Breaks for Pass-Through Business Owners | |

| Expand Limit on Business Losses | $76 billion |

| Prevent Partnerships from Shifting Basis | $15 billion |

| Partly Reversing the Trump Personal Income Tax Cuts for the Rich | |

| Reverse Trump Cut in Top Tax Income Tax Rate | $246 billion |

| Ending Tax Breaks for Dynastic Wealth | |

| Close Loopholes in Estate Tax | $97 billion |

| Reforming Tax Rules Related to Crypto | |

| Reform Tax Rules for Digital Assets | $26 billion |

| Creating a More Energy-Sustainable Tax Code | |

| Repeal Fossil Fuel Tax Breaks | $35 billion |

| Reforming Retirement Tax Breaks | |

| Limit Retirement Tax Savings Breaks for the Wealthy | $24 billion |

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 2024

Partly Reversing the Trump Corporate Tax Cuts

Raise Corporate Tax Rate from 21 Percent to 28 Percent

10-Year Revenue Impact: $1.4 trillion

The President’s budget would partly reverse the cut in the corporate income tax rate that was signed into law by former President Trump as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). President Biden’s plan would raise the corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent, still lower than the 35 percent rate that applied to most corporate profits before TCJA came into effect. As explained below, the arguments in favor of a lower corporate tax rate were always weak and based on misunderstandings of how corporations respond to tax changes.

Corporate tax cuts did not make American companies more competitive.

- Drafters and supporters of TCJA claimed that the rate cut would make the United States more globally competitive. But it is not the case that the pre-TCJA corporate tax code made the United States less competitive than other countries or the that the rate cut made the U.S. more so.

- The United States accounts for just over 4 percent of the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP, but American corporations account for 50 percent of the market value and a third of the sales of the Forbes Global 2000, which is an annual list that measures the largest businesses in the world based on sales, profits, assets, and market value. These figures were essentially the same in 2017, before the TCJA was enacted and in the years that followed. American corporations had a huge advantage and that has not changed.

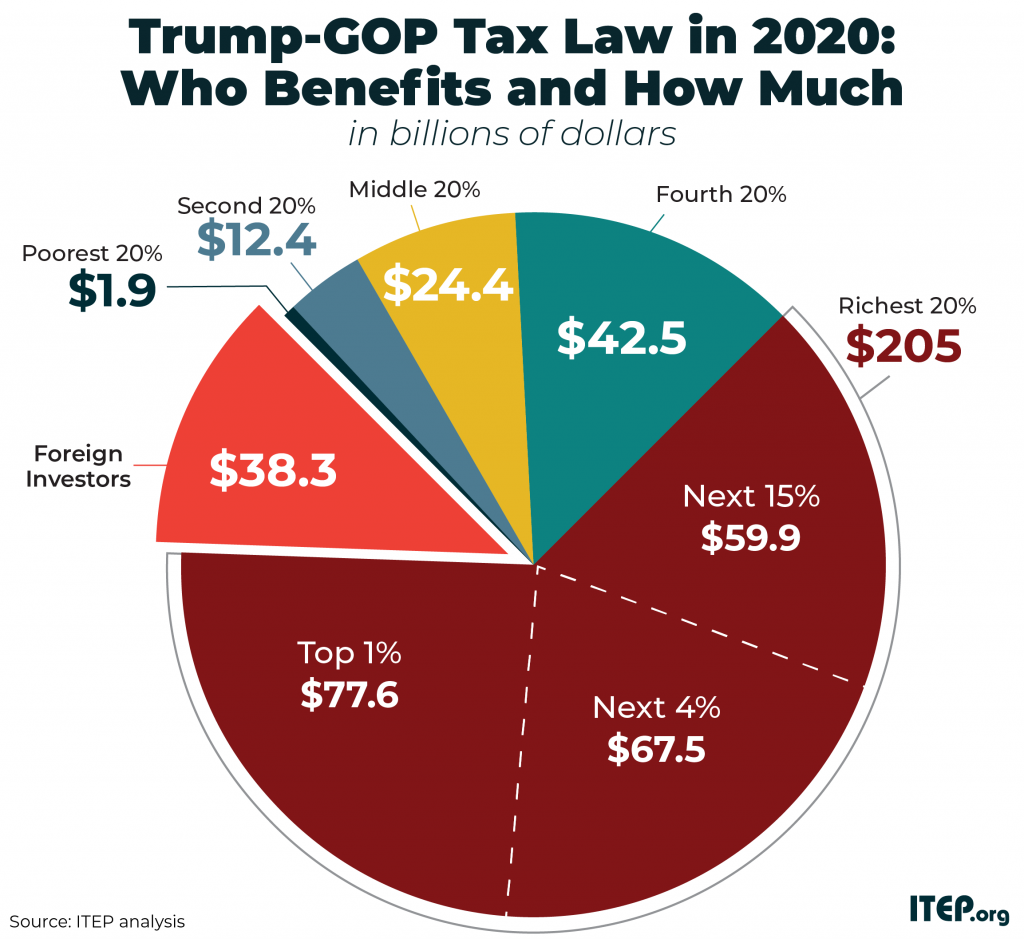

Corporate tax cuts benefit shareholders, who are mostly wealthy Americans and foreign investors.

- Congress’s official revenue-estimator, the Joint Committee on Taxation, has concluded that most of the benefits from corporate tax cuts flow to the owners of corporate stocks and other business assets, who are mostly wealthy. Recent research has concluded that a great deal of the benefits also flow to foreign investors, who own an estimated 40 percent of the shares of American corporations. Altogether, the richest 1 percent of Americans and foreign investors received most of the benefits of the corporate tax cuts enacted under former President Trump.

Corporations used their tax cuts to enrich shareholders with stock buybacks, not to invest and create jobs.

- In the first four years after these corporate tax cuts went into effect, the largest American corporations collectively spent more on enriching their shareholders through stock buybacks ($2.72 trillion) than on investments in plants, equipment, or software that might have created new jobs and grown the economy ($2.65 trillion).

Corporations would not lobby for corporate tax cuts if they thought their shareholders were not the beneficiaries.

- Corporations are created to build wealth for their shareholders, and the CEO and management of a corporation ultimately serve the shareholders. And corporate executives themselves usually own a lot of stock in the company they work for. Given how much corporations lobby for corporate tax breaks, it is quite clear that the corporate executives themselves believe that the benefits go to the stock owners.

Increase the IRA’s Minimum Corporate Tax Rate from 15 Percent to 21 Percent

10-Year Revenue Impact: $137 billion

The corporate minimum tax, which was enacted as part of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and which went into effect in 2023, requires the largest corporations to pay federal tax of at least 15 percent of the profits they report to their shareholders. President Biden proposes to increase the corporate minimum tax rate to 21 percent.

The IRA’s minimum tax was enacted as a backstop to the regular federal corporate income tax which has a statutory rate of 21 percent but allows most corporations to effectively pay much less than that because of its many special breaks and loopholes.

A recent study from ITEP finds that in the first five years since the corporate income tax rate was set at 21 percent, the Fortune 500 companies and S&P 500 companies that were consistently profitable during that period effectively paid a rate of just 14.1 percent.

The ITEP study also identifies 55 corporations that paid effective rates of less than 5 percent (including several that paid nothing) over the five-year period despite reporting profits to investors and the public each year.

The IRA’s minimum tax, which went into effect in 2023 (after the period covered by ITEP’s study), will mitigate at least some of this tax avoidance for the very largest companies. This minimum tax applies to corporations that report annual profits averaging more than $1 billion over the previous three years. One study found that 78 companies would have been affected by the provision if it had been in effect in 2021.

President Biden proposes to increase the rate of this minimum tax from 15 to 21 percent, which is consistent with his other proposals. The President proposes to also raise the main statutory corporate tax rate from 21 to 28 percent and to enact a 21 percent minimum tax on offshore profits of corporations to crack down on their use of offshore tax havens, as described further on.

Preventing Tax Avoidance on Corporate Transfers of Income to Executives and Shareholders

Tighten the $1 Million Limit on Deductions for Compensation

10-Year Revenue Impact: $272 billion

The President proposes to strengthen the tax code’s section 162(m), which limits deductions that corporations take for compensation to $1 million in certain situations.

Until recently, section 162(m) had an exception for performance-based pay (like stock options) and only applied to the top five executives in any given company. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) removed the exception for performance-based pay (but grandfathered in existing stock options). And the American Recovery Plan Act (ARPA) generally expanded the number of employees covered from 5 to 10. But any employees beyond that are not covered. Nor are any employees of privately held companies because section 162(m) applies only to publicly traded companies.

The President’s proposal would expand the $1 million cap on deductions for compensation to apply to any employees of a corporation, whether it is privately held or publicly traded.

Increase Stock Buyback Excise Tax from 1 Percent to 4 Percent

10-Year Revenue Impact: $166 billion

President Biden and Congress enacted a 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. The initial evidence suggests the tax has had little or no effect on corporations’ decisions to repurchase their own stocks, which means the tax could potentially collect more revenue at a higher rate. It also appears that the tax is not high enough to eliminate the tax advantage for stock buybacks over other methods that corporations use to send profits to shareholders. For these reasons, the President proposes to increase the stock buyback excise tax that is in effect now under the IRA from 1 percent to 4 percent.

While corporate dividends paid to shareholders are subject to the personal income tax in the year they are distributed, stock buybacks effectively give the same financial benefit to shareholders by boosting stock values but can remain untaxed for years or in some cases forever. The stock buyback tax can reduce that disparity, but its current rate of 1 percent is not high enough to eliminate it.

See ITEP’s more detailed explanation of the stock buyback proposal.

This proposal is expanded slightly in this year’s budget to apply also to “controlled foreign corporations,” which are often offshore subsidiaries of U.S. corporations.

End Abuses of Tax-Free Spin-Offs

10-Year Revenue Impact: $44 billion

The President proposes to block corporations from avoiding taxes by hiding payments to shareholders or unloading of debts in arrangements that appear to be corporate spin-offs.

When a corporation transfers assets to shareholders, the tax code usually requires the company to pay tax on any gain on the assets, just as if the company had sold them. Similarly, if a corporation’s debt is forgiven, this debt forgiveness is taxable income for the company.

The tax code allows exceptions when a corporation splits part of itself off into a new company. For example, if a corporation decides to spin off its widget operations into a new company, it might distribute certain assets (a widget factory and its machinery) to a newly created company in return for stock in the new company, which it then distributes to its shareholders. In theory, the point of the arrangement was to reorganize the business, not pay shareholders, so the tax code does not tax gains on assets in this situation the way it would if they were sold.

However, when anything other than stock is received in return for the transfer of assets to the spun off company, the situation becomes more complicated and the opportunity for abuse is much greater. The President’s proposal would tighten the existing rules so that the corporation distributing its assets to a newly created company may have to pay tax on capital gains in some situations. It would also create rules to ensure that the newly created company is not simply overloaded with debt but is in fact a financially viable business.

Stopping Offshore Corporate Tax Avoidance

Revise Global Minimum Tax Rules

10-Year Revenue Impact: $374 billion

American corporations often use accounting gimmicks to disguise profits earned in the United States (or in a country with a comparable tax system) as profits earned in offshore tax havens, which are countries with no corporate tax or only a weak one. This proposal would greatly reduce the tax breaks that corporations can acquire through these schemes.

Enacting these reforms would bring the United States into compliance with the international agreement that the Biden administration negotiated with the Organization for Cooperation and Development (OECD) and most of the world’s governments to create a global minimum tax. Here are some of the most important parts of this proposal:

Reducing the gap between effective tax rates for offshore profits and domestic profits.

- When corporations are allowed to pay less on offshore profits than on domestic profits, this encourages accounting schemes that make more profits appear to be earned in low-tax countries.

- The current rules enacted as part of the Trump tax law create this result, allowing American corporations to pay an effective tax rate on offshore profits (10.5 percent) that is half the effective rate they pay on domestic profits (21 percent). The President proposes to reduce this gap by allowing an effective rate for offshore profits that is three-fourths of the domestic rate (21 percent for offshore profits compared to the 28 percent rate he proposes for domestic profits).

- This would be more than sufficient to implement the global minimum tax that the Biden administration negotiated with the international community, which requires participating countries to ensure that their corporations pay an effective tax rate of at least 15 percent on their offshore profits.

Applying the minimum tax per country to prevent corporations from using high taxes paid in one country to offset very low taxes paid in another country.

- To the extent that the current rules require corporations to pay a minimum tax on their offshore profits, the minimum tax is calculated on worldwide basis rather than a per-country basis, which makes it easier for multinational companies to avoid it.

- For example, a company could have profits in Country A where it pays an effective tax rate of just 5 percent but still be able to avoid the worldwide minimum tax if it pays an effective rate of 25 percent on profits in Country B. Its overall effective tax rate calculated on its offshore profits could be more than the minimum rate required.

- The President’s proposal would calculate the minimum tax separately for each country where the corporation reports that it earns profits.

Eliminating the exemption for certain offshore profits

- Under current law, some offshore profits of American corporations are not taxed at all because they fall within an exclusion (equal to a 10 percent return on tangible offshore investments like plants and equipment). The drafters believed that a 10 percent or less return on investments and personnel is likely to be real profits generated from real business and not the result of accounting gimmicks that merely shift numbers around to make profits to appear to be earned in low-tax countries.

- Of course, the 10 percent threshold is arbitrary. Even worse, it could encourage companies to actually move investment and jobs offshore to claim the exemption for more of the profits they already report to earn offshore.

- The President proposes to eliminate this exemption.

Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR)

10-Year Revenue Impact: $136 billion

As already explained, the Biden administration negotiated an agreement among most of the world’s governments to ensure that their corporations pay an effective tax rate of at least 15 percent on their offshore profits. Another part of that agreement is the “undertaxed profits rule,” or UTPR, designed to address the concern that some countries might refuse to participate, giving their corporations an unfair advantage.

The UTPR would address this problem by allowing participating countries to impose a “top up” tax on foreign-owned corporations operating in their borders if they are based in a country that does not require them to pay a total tax rate of at least 15 percent.

The President’s proposal would implement the UTPR by limiting deductions for US taxes for subsidiaries or branches of a low-taxed, foreign-owned company operating in the US. Under current law, these deductions are often used to strip earnings out of the United States and shift them to countries where they will not be taxed.

Under the international agreement, countries imposing a top up tax under the UTPR would allocate the revenue raised amongst themselves through a formula (based on employees and assets a corporation has in each country), which the President’s proposal spells out. The proposal would apply to foreign-based corporations with global annual revenue of at least €750 million (or about $820 million).

Repeal the Deduction for Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII)

10-Year Revenue Impact: $158 billion

The deduction for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) was enacted as part of the Trump tax law. It is based on the idea that income companies earn from intangible assets like patents and copyrights is particularly easy to shift offshore. The drafters thought they could deal with this by allowing American corporations a deduction when such assets are held in the U.S. and generate income (like royalties) from foreign customers.

But the FDII deduction is another provision that could encourage companies to move investment offshore. The law defines FDII simply as profits in the U.S. from selling to foreign markets minus 10 percent of the value of tangible assets held in the U.S. The reasoning is that any profits beyond this amount must be from intangible assets, but that is not necessarily true. (The 10 percent threshold is arbitrary.) Corporations could move investment offshore to increase the amount of income that is considered FDII and thus eligible for the FDII deduction.

The President proposes to repeal the FDII deduction and put the revenue towards tax breaks that administration officials believe will more effectively encourage companies to conduct research.

Address “Dual Capacity Taxpayer” Fossil Fuel Companies

10-Year Revenue Impact: $72 billion

The President proposes to prevent American corporations that extract fossil fuels from abroad from characterizing royalties they pay to foreign governments as taxes that reduce their U.S. taxes.

American corporations with offshore operations are allowed to claim a credit against their U.S. taxes for taxes they pay to foreign governments, to prevent double taxation. Some multinational companies, particularly those that extract fossil fuels, make payments to foreign governments in return for specific economic benefits, like royalties paid in return for permission to drill. Corporations that are effectively paying both income taxes and royalties to a foreign government, often called “dual capacity” taxpayers, may characterize much of their royalties as taxes, increasing the foreign tax credits they use to reduce U.S. taxes.

The President’s proposal would ensure that dual capacity taxpayers cannot claim foreign tax credits for payments that are not truly corporate income taxes that any type of company operating in the foreign country would pay on its profits.

Bar Earnings Stripping Through Excessive Interest Deductions

10-Year Revenue Impact: $40 billion

The President proposes to prevent multinational corporations from manipulating debt as an accounting gimmick to strip earnings out of the United States.

A foreign corporation can “loan” money to its U.S. subsidiary, which then makes large interest payments back to the foreign parent company. The U.S. subsidiary deducts the interest payments from its U.S. income and tells the IRS that it has little or no taxable income as a result.

In these situations, the parties on both sides of the transactions are really controlled by the same people. The “borrower” and “lender” are parts of the same company. These arrangements exist only on paper and only to shift profits out of the U.S. to a foreign country with a low tax rate or no corporate tax at all.

The President’s proposal would bar deductions for interest payments made by the U.S. subsidiary of a multinational corporation if that subsidiary is carrying a disproportionate share of the debt held by the entire corporation.

Strengthening Medicare Taxes on the Rich

Close Loophole in Medicare Taxes for Certain Business Profits

10-Year Revenue Impact: $393 billion

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made two tax changes to better fund Medicare. First, it modified the 2.9 percent Medicare payroll tax to effectively have a higher bracket of 3.8 percent for high-earning individuals. Second, it created a comparable 3.8 percent tax on investment income for high-income households. The general idea was that well-off people would pay a 3.8 percent tax to help finance Medicare, whether their income was earned or from investments. But one of the compromises made to secure enactment created a loophole and allowed a long-standing scheme to avoid the Medicare payroll tax to continue, allowing certain business profits (or income described as business profits) to escape both taxes.

Individuals who are actively involved in managing a business that they own often distribute profits to themselves that are not subject to the Medicare payroll tax. The compromise made in drafting the ACA ensured that the newly created 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) would not apply to these distributed profits either.

This also left in place the technique used by some individuals to route what is really earned income through a business entity as a distributed profit, in order to avoid paying Medicare taxes.

The President’s proposal would ensure that such profits would be subject to either the Medicare payroll tax or the NIIT (meaning high-income people pay a 3.8 percent tax on those profits one way of the other). This reform would be phased in for those with incomes between $400,000 and $500,000.

See ITEP’s more detailed explanation of the President’s proposals to strengthen Medicare taxes on the rich.

Increase Medicare Taxes for the Rich from 3.8 Percent to 5 Percent

10-Year Revenue Impact: $404 billion

Currently, high-income people pay a 3.8 percent tax on most types of income to help fund Medicare. This is accomplished with two different taxes. One is the Medicare payroll tax on earnings, which effectively has a top rate of 3.8 percent. The other is a 3.8 percent tax on investment income that only applies to high-income people. The President’s proposal would add a 5 percent bracket to both taxes for people making more than $400,000, requiring them to pay an additional 1.2 percent compared to what they pay now.

Limiting Tax Breaks for Capital Gains

Billionaire Minimum Income Tax

10-Year Revenue Impact: $503 billion

Most people think of a capital gain as the profit one receives when selling an asset for more than it cost to acquire it. But when an asset becomes more valuable, that asset appreciation can also be thought of as income for its owner, even if they do not sell the asset. Economists consider these “unrealized capital gains” to be income, but the tax code usually does not.

As a result, wealthy people can defer paying income taxes on gains until they sell assets, and this is a major tax break for capital gains. The President’s proposed Billionaire Minimum Income Tax would limit this tax break and would be phased in for taxpayers with a net worth between $100 million and $200 million.

Those wealthy enough to be subject to the proposal would generally be required to pay at least 25 percent of their total income, including unrealized capital gains, each year.

When this equals more than they owe under the regular tax rules, affected taxpayers would have five years to pay the difference (nine years for the tax assessed in the first year the proposal is in effect). This gradual payment would smooth out long-term calculations of the tax for someone whose assets fluctuate dramatically in value. If unrealized gains in one year are followed by unrealized losses in another year, only a portion of the minimum tax is paid for the first year and then potentially refunded in the following year. Payments of the minimum tax would also serve as prepayments of the tax that would otherwise be due later when a taxpayer sells an asset or passes it to an heir.

Some other proposals, like Sen. Ron Wyden’s “Billionaires Income Tax” create something closer to a “mark-to-market” system of taxation, which would treat unrealized gains as income each year. The President’s proposal is different because it is structured as a minimum tax, ensuring that very wealthy people pay at least 25 percent of their total income, including the unrealized gains that escape taxation under current law.

See ITEP’s more detailed explanation of these proposals.

Limit Capital Gains Breaks for Millionaires

10-Year Revenue Impact: $289 billion

The President also proposes to sharply limit two other tax breaks for capital gains.

First, current rules tax capital gains (when they are realized) at lower rates than other types of income. In effect this means that people who live off their investments can pay lower tax rates than people who work for their income.

Currently, income from capital gains and dividends is taxed at a top personal income tax rate of just 20 percent, compared to a top rate of 37 percent for ordinary income (39.6 percent under the President’s budget). The White House proposes to tax all income over $1 million at the top ordinary personal income tax rate regardless of whether it is capital gains, dividends, or some other type of income.

Second, current rules entirely exempt capital gains on assets that a taxpayer does not sell before the end of their life. In other words, unrealized capital gains on assets passed to heirs are never taxed.

This break is sometimes called the “stepped up basis” rule. When assets are passed on, the heirs receive those assets at a basis (original value) set to the date at which the assets are inherited. For example, if some asset is originally purchased at a value of $50 million and is then passed to an heir at a current value of $100 million, the heir can immediately sell the asset for $100 million without reporting any capital gain. This rule allows an enormous amount of capital gains to go untaxed.

The President’s budget would partially address this problem by treating unrealized gains as taxable income for the final year of a taxpayer’s life. Still, generous exemptions would apply. This proposal would exempt $5 million of unrealized gains per individual and effectively $10 million per married couple. The President also proposes allowing any family business (including farms) to delay the tax if the business continues to be family-owned and -operated.

Limit Like-Kind Exchanges

10-Year Revenue Impact: $20 billion

President Biden proposes to bar taxpayers from using “like-kind exchanges” to shield more than half a million dollars of capital gains from income taxes.

Capital gains on property sales can be the main type of income received by large-scale real estate investors, but they can avoid paying taxes on this income by structuring their transactions as “like-kind” exchanges. In these deals, one property is traded for another similar property rather than sold for cash. (The transfer can also be partly for cash and partly a like-kind exchange.) The general idea is that no income tax is due on a profit from the sale to the extent that the seller received another property rather than cash.

This policy was originally intended as an administrative convenience in situations where farmers traded land or livestock without any money changing hands. Today, the definition of like-kind is extremely generous, “allowing a retiring farmer from the Midwest to swap farmland for a Florida apartment building tax-free,” according to the Congressional Research Service. The New York Times has reported that Jared Kushner, who is heavily invested in real estate, avoided paying income taxes for several years, partly by using like-kind exchanges.

Limiting Tax Breaks for Pass-Through Business Owners

Expand Limit on Business Losses

10-Year Revenue Impact: $76 billion

Under rules enacted as part of Trump tax law, when business owners report losses, they cannot use these losses to offset more than $305,000 of their non-business income (or $610,000 of non-business income for married couples). One of the rare provisions of the 2017 law that limited tax avoidance for the wealthy, this prevents high-income taxpayers from deducting business losses that exist only on paper to reduce the other income they report to the IRS.

The limit on business losses was set to expire after 2025. The CARES Act controversially suspended it for 2020 and retroactively for 2018 and 2019. The American Rescue Plan Act extended it for one year, through 2026. The Inflation Reduction Act extended it for another two years, through 2028.

The President’s proposal would make two changes.

First, it would make the limit stricter by imposing the $289,000/$578,000 limit on excess losses even after the year when those losses are reported. (Under the current rules, after excess losses are carried into the following tax year they are treated as net operating losses, which are not subject to the same limit.)

Second, it would make the limit permanent.

Prevent Partnerships from Shifting Basis

10-Year Revenue Impact: $15 billion

The budget includes a reform that would prevent related partners in business partnerships from generating deductions by shifting the “basis” among themselves.

The “basis” is usually the amount a taxpayer has invested in an asset and is used to calculate the income generated from selling the asset. For example, if a taxpayer buys an asset for $3,000 and, a few years later, sells it for $10,000, the income generated from the sale is calculated by subtracting the $3,000 basis from the $10,0000 sale price, which comes to a capital gain of $7,000. In some situations, determining the basis can be more complicated, particularly when assets are owned by a partnership rather than a single individual.

Under current law, related partners in partnerships can generate tax losses on the distribution of property. This can happen when one partner receives property from the partnership that is greater in value than their actual investment (basis) in the partnership.

For example, if a partner who has invested $100,000 in the partnership receives property with a basis of $150,000 from the partnership in redemption, their basis in the property is stepped down to $100,000 (representing the partner’s “outside” basis in the partnership). In theory, this means if they sold the property immediately and received $150,000, they would pay income taxes on a gain of $50,000. (The $150,000 sale price minus the $100,000 basis comes to a capital gain of $50,000.)

The tax rules allow the partnership to offset that step-down in basis for the partner receiving the property by stepping up the basis for the remaining property in the partnership. In this example, if the remaining property held by the partnership is worth $200,000 and has a basis of $100,000, the basis would be stepped up to $150,000. This reduces the capital gains that would be taxed (in the event that the partnership sells its property) by $50,000. If the property is depreciable, the remaining partner can immediately start claiming depreciation deductions relating to the stepped-up basis of $50,000.

In an ideal world, the step-down of basis for the partner receiving property would be perfectly offset by the step-up in basis for the other partner or partners. In this example, if all the partners sell the property involved, the $50,000 increase in income for one taxpayer is offset by a $50,000 decrease in income for others. Unfortunately, this is not what usually happens in real life. Often the partner with the stepped-down basis never sells the property, meaning, in this example, the $50,000 gain is never taxed. The property remaining with the other partner(s) is often depreciable property, so their step-up in basis results in tax deductions they can claim right away. The transfer is often used to shift basis from non-depreciable property to depreciable property to maximize these tax deductions.

President Biden’s budget calls for a new rule that would allow the remaining related partner to benefit from the step-up in basis only after the property is sold and has become a taxable gain.

Partly Reversing the Trump Personal Income Tax Cuts for the Rich

Reverse Trump’s Cut in Top Tax Income Tax Rate

10-Year Revenue Impact: $246 billion

The President’s budget would reverse the provision in the Trump tax law that cut the top marginal personal income tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent. The proposal would also make the top rate apply to single taxpayers with taxable income exceeding $400,000 and married couples with taxable income exceeding $450,000, which is lower than the floor for the top income tax bracket in effect now.

This provision would raise the most revenue from 2024 and 2025, the years when the personal income tax cuts are in effect under the 2017 tax law. After 2025 it would continue to raise some revenue compared to current law because it would apply the top income tax rate at a lower level of taxable income than would be the case under current law.

Ending Tax Breaks for Dynastic Wealth

Close Loopholes in Estate Tax

10-Year Revenue Impact: $97 billion

The President’s budget includes several proposals to close loopholes in federal estate and gift taxes. The most important of these proposals address the ways that wealthy people use trusts to avoid taxes.

The tax code should prevent wealthy people from avoiding taxes when they transfer assets to other people. Normally, a wealthy person would pay federal gift tax if they give away an asset to a family member or friend, and their estate could be taxed if they bequeath the asset to them when they die. (These taxes exempt the first $13.6 million given or bequeathed by an individual this year, and the first $27.2 million for married couples.) The taxpayer could sell the asset to their friend or family member but would pay income tax on any capital gain.

The problem is that loopholes in our tax laws allow wealthy people to use trusts to avoid federal taxes in all these situations when they transfer assets (usually to family members). These loopholes effectively subsidize the transfer of huge sums of wealth down through generations within a dynasty. This is especially true of assets that owners expect to appreciate significantly over the coming years.

Wealthy people use two tactics to transfer these assets to others (usually heirs) without paying gift or estate tax on the subsequent increase in the assets’ value.

First, a wealthy person can place assets in a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT), which is structured to provide an annuity payment from the assets. The trust is arranged to give the remaining value of the assets – any value that the assets have above and beyond what will be paid back to the grantor in annuity payments – to the beneficiaries of the trust as a gift, which is subject to the federal gift tax.

However, wealthy people often create “zeroed out” GRATs, meaning the gift (the value of the assets beyond the annuity payments) is zero according to the formula specified in the tax law.

Over the duration of the trust, sometimes that turns out to be true – the assets might perform only as well or more poorly than calculated, meaning there really is no gift to the trust beneficiaries – and the grantor takes back the assets placed in the trust.

But if the assets perform better than expected, the trust pays the annuity payments to the grantor and then the remaining assets go to the trust as a tax-free gift. The formula used to determine the value of the assets when the trust was set up (which determined that no taxable gift was provided to the beneficiaries of the trust) is never retroactively corrected. This means that asset value has been passed to the trust beneficiaries (usually family members of the grantor) without triggering the federal gift tax or estate tax that would normally be due on such a transfer.

Wealthy people set up multiple GRATs knowing that they will avoid taxes whenever the assets in the trusts perform better than expected under the formula used in the law, and that they will lose nothing when the assets do not.

Second, a grantor can set up a trust and sell an asset to it. No gift tax applies because the transfer was a sale, not a gift. For purposes of the income tax, the sale has not occurred at all because the grantor owns the trust, which means no tax is due on any capital gains. But for purposes of the gift and estate taxes, the asset is owned by the trust (and eventually, its beneficiaries), which means that any further increase in the value of the asset will be free of gift and estate tax. Further, the grantor can make additional gifts to the trust free of tax by paying the income taxes due on the income generated by the assets in the trust.

The President’s proposals would make GRATs far less attractive by barring zeroed out GRATs (requiring a minimum amount of the initial transfer when the trust is created to be subject to gift taxes) and requiring the trust to have a duration of at least 10 years to make it less common for assets to outperform and create untaxed gifts. It would make sales to grantor trusts taxable events and would count income taxes paid on behalf of trusts as taxable gifts to the trust.

Reforming Tax Rules Related to Cryptocurrency

Apply Wash Sale Rules to Digital Assets and Make Related Reforms

10-Year Revenue Impact: $26 billion

After several years of tumultuous cryptocurrency performance and scandals involving major asset exchanges, many policymakers have sought more careful regulation of digital markets. As one step in this process, the President’s budget would prevent taxpayers from avoiding taxes by abusing losses from digital assets in the same way that the tax code already limits losses for other types of assets.

Taxpayers pay personal income taxes on their net capital gains, which is their combined capital gains (profits from selling appreciated assets) and capital losses (losses from selling depreciated assets) when the net result is positive. Wealthy taxpayers with significant investments therefore have an incentive to realize as many capital losses as possible to offset any capital gains.

The “wash sale rules” bar taxpayers from deducting losses from stocks and other securities that they repurchase less than 30 days after selling them at a loss. Without these rules, an investor who fully intends to remain invested in a company might simply sell their shares in the company when they are down to deduct the losses and then immediately repurchase them. This would further exacerbate the bias in the tax system that allows investors to sell assets whenever they can realize a deductible loss but hold onto appreciating assets to defer paying income tax on the gains.

The President proposes to extend the wash sale rules to digital assets. Under current law, an individual might sell a digital asset at a loss one day and then repurchase the exact same asset the next day, and still claim a deduction for the loss even though they have not really relinquished the asset in any meaningful way or changed their economic position in terms of that asset. Given the recent significant problems in the market for crypto and other digital assets that Congress has failed to regulate, it seems sensible to subject them to the same limits that apply to other assets, at the very least.

Creating a More Energy-Sustainable Tax Code

Repeal Fossil Fuel Tax Breaks

10-Year Revenue Impact: $35 billion

The White House proposes closing a variety of tax breaks that benefit fossil fuel producers. The largest subset of these tax breaks provide special expensing, depreciation, and amortization breaks for oil and gas production. These tax benefits allow fossil fuel companies to write off their costs more quickly, thus reducing their final tax bill.

The tax code also provides special credits and benefits to producers when oil and gas prices are exceptionally low or to producers who are using more costly wells. Another subset of benefits creates special business and income rules for fossil fuel companies, for example, allowing corporate income to be treated as partnership (pass-through) income.

Finally, the administration would repeal several provisions that allow fossil fuel companies to reduce their contributions to the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, an important and immediate source of funds for federal agencies to respond to oil spills.

Reforming Retirement Tax Breaks

Prevent Abuse of Retirement Tax Breaks by the Wealthy

10-Year Revenue Impact: $24 billion

Congress has long used tax breaks to encourage Americans to save for retirement. Unfortunately, this has mainly benefited those who have comfortable incomes and would save anyway. (See ITEP’s explanation of how Congress recently made this problem worse.) The President proposes to limit some of the worst abuses of these tax breaks that turn them into unwarranted tax shelters for the rich.

Americans typically pay taxes on their income and are usually not allowed to defer income taxes until future years, because doing so would effectively allow tax avoidance. A tax liability to be paid in the future is worth less than a tax liability of the same amount due today because of inflation and discounting. (If you owe $100 in taxes but you can wait ten years before you pay it, you have effectively avoided tax because $100 will be worth less in a decade than it is worth now and you could have invested it and generated more income.)

However, Congress makes exceptions and allows tax deferrals and other tax breaks to encourage people to save for retirement, often allowing people to defer paying income tax on a certain portion of the compensation we save in 401(k) plans or Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) until we withdraw the money in retirement. The tax breaks that delay income taxes until retirement often result in much larger savings to draw down later in life.

A Roth IRA achieves something similar but through a different route. Taxpayers are not allowed to defer income tax on the income they place in a Roth IRA (meaning contributions are not tax-deductible like contributions to traditional IRAs) but the income distributed from a Roth IRA during retirement is tax-free. Whereas most tax breaks for retirement savings allow a deduction on the money flowing into the account and tax the income coming out during retirement, the Roth IRA does the reverse. The details are complicated, but in theory the savings for the taxpayer can be about the same.

The rules become complicated because tax breaks for retirement must include limits to prevent them from being tools for general tax avoidance. Unfortunately, these rules often fail. Despite the strict limits on contributions to a Roth IRA, the tech mogul Peter Thiel has a Roth IRA worth $5 billion. Thiel placed business assets in his Roth IRA several years ago, apparently claiming they were worth no more than the contribution limits. Now those assets are worth $5 billion, meaning he generated $5 billion of income on which he will never pay income taxes. (Remember, contributions to a Roth IRA are not deductible but income coming out of a Roth IRA is tax-free.)

The President proposes several changes. The most fundamental would require withdrawals from tax-favored savings vehicles when their value exceeds certain thresholds. If a taxpayer has more than $10 million total in tax-favored retirement accounts, they must withdraw at least half of the excess beyond that threshold (ending the tax savings for the amount withdrawn). If they have more than $20 million total in such accounts, they must withdraw 50 percent of the excess and their withdrawal cannot be less than the total amount they hold in Roth-style savings vehicles.