Key Findings

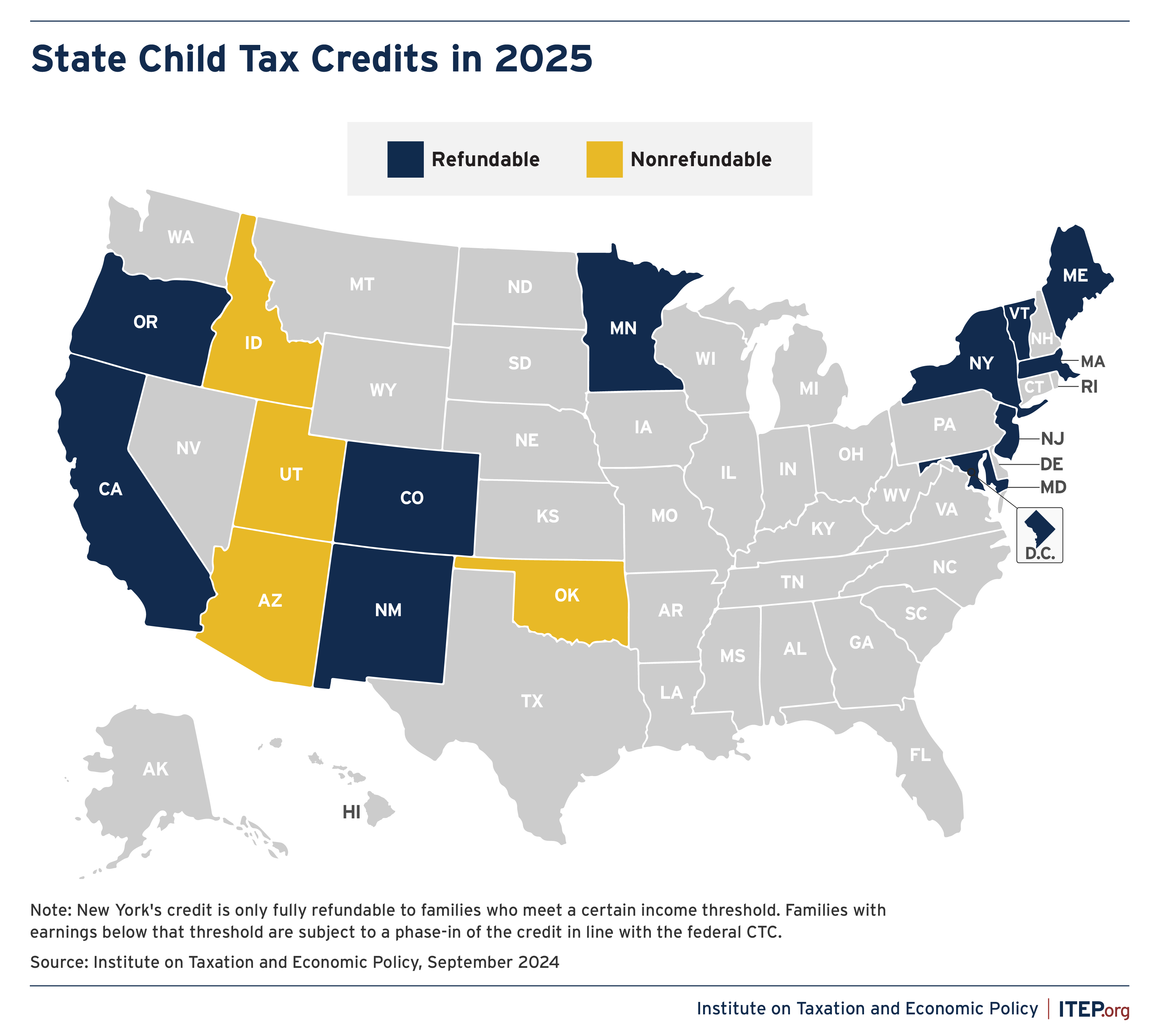

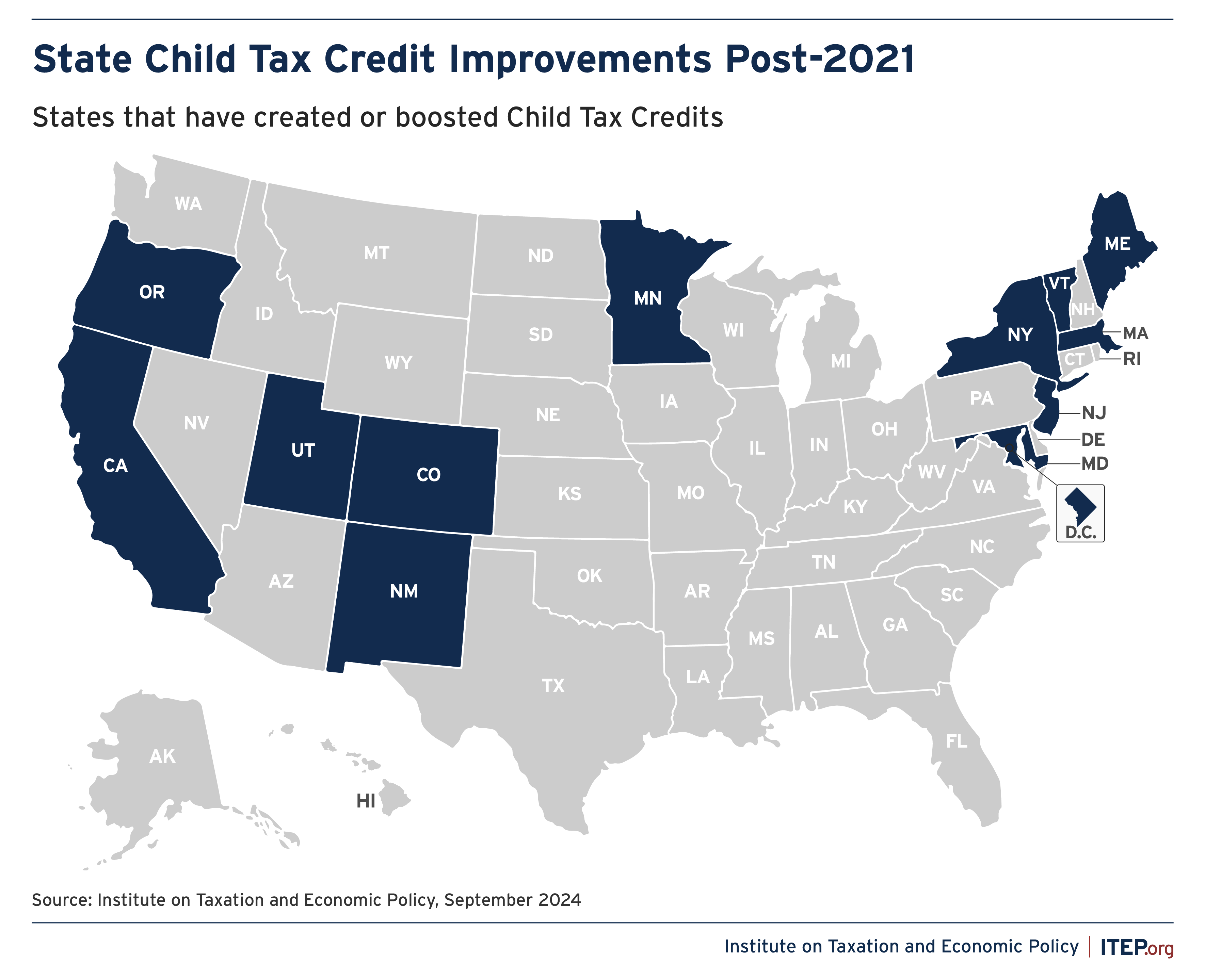

- Fifteen states plus the District of Columbia provide Child Tax Credits to reduce poverty, boost economic security, and invest in children. States with fully refundable Child Tax Credits in 2025 are California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, and Vermont. Arizona, Idaho, Oklahoma, and Utah offer nonrefundable credits.

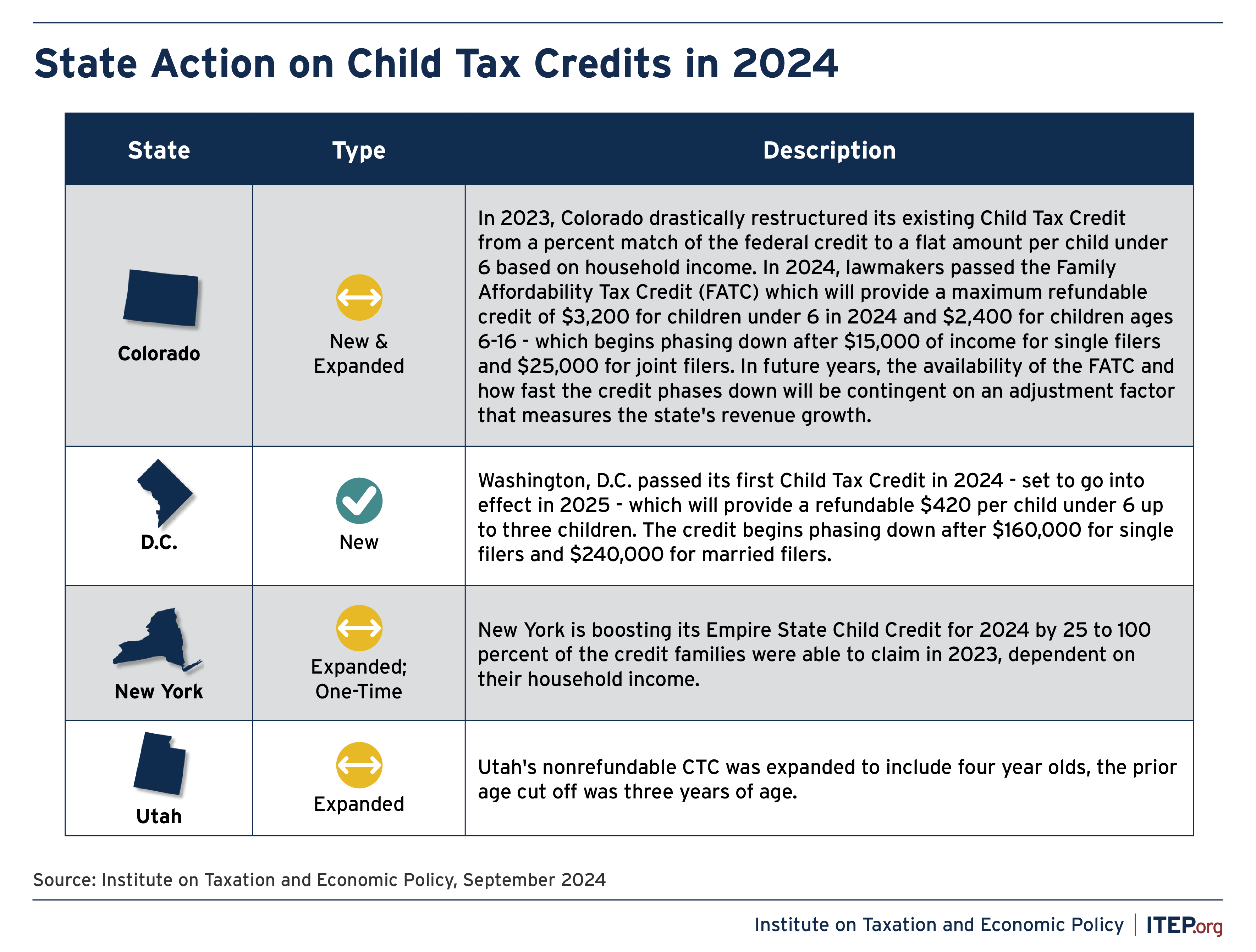

- This year alone, lawmakers in three states – Colorado, New York, and Utah – expanded their Child Tax Credits while lawmakers in the District of Columbia created a new credit that will take effect in 2025.

- State Child Tax Credits are larger than ever before, with five states – Colorado, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, and Vermont – offering refundable credits at or above $1,000 per qualifying child. In all states collectively, these credits amount to a multibillion-dollar investment in children each year.

- To maximize impact, lawmakers should consider making their credits fully refundable, not including an earnings requirement, setting a maximum amount per child instead of per household, setting state-specific phase-out ranges that target low- and middle-income families, indexing to inflation, and offering the option of advanced payments.

Introduction

Child Tax Credits (CTCs) are effective tools to bolster the economic security of low- and middle-income families and position the next generation for success. When designed well, they build on the powerful base of the federal CTC, counteract some of its deficiencies, and lead to meaningful reductions in child poverty and deep poverty.[1]

More state lawmakers are choosing to help families in this way: for the 2025 tax year, 15 states and the District of Columbia will provide Child Tax Credits, many of which are targeted to those who most need them and refundable so children in the lowest-income families are not excluded from the full benefits. Together these credits constitute an annual multibillion-dollar investment in the next generation. As more states consider creating or strengthening these credits, lawmakers should design them for maximum impact.

Child Tax Credits: A Critical Tool to Help Families Make Ends Meet

Refundable Child Tax Credits boost the after-tax incomes of qualifying families and offset some of the costs of raising children. These policies are especially important for the economic security and stability of lower-income families, helping them avert unexpected hardship that can threaten basics like housing, food, and utilities. Child Tax Credits are associated with reduced poverty, higher financial and household stability, improved child and maternal health, better educational achievement, stronger future economic outcomes, and more.[2]These benefits are stronger with well-designed credits.

CTCs help families of all races. When designed well, these credits are particularly helpful to the lowest-income families and can make up for some of the damage done by other policies that hurt poor children and particularly harm Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous children.[3] Economic inequality, low wages, and child poverty are defining challenges in the U.S. Historic and ongoing discrimination mean these problems disproportionately harm Black families and other families of color. CTCs help address these challenges.

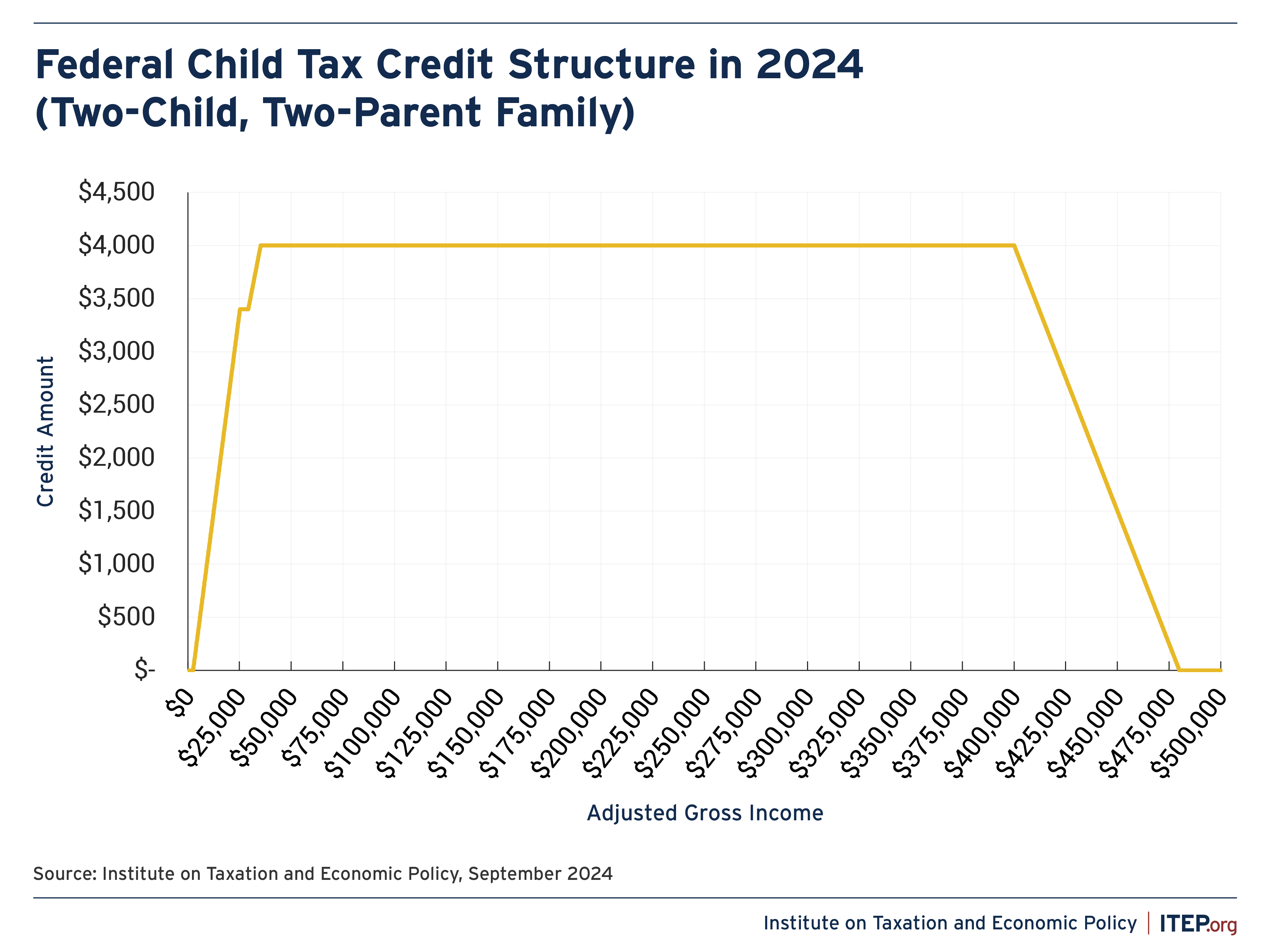

The federal CTC provides a credit of up to $2,000 for each dependent child under age 17. It phases out for married couples with incomes above $400,000 and for unmarried parents with incomes exceeding $200,000.

The federal CTC excludes some low-income families from receiving the full credit by requiring a minimum level of earnings and by not making the credit fully refundable to those whose income tax payments are smaller than the credit they would otherwise receive. Children whose parents or guardians earn less than $2,500 are ineligible for the federal CTC while families with earnings above this level receive a federal CTC limited to 15 percent of each dollar of earnings over $2,500 (until reaching a maximum credit of $2,000 per child).

The CTC is also only partially refundable, meaning that families can only receive $1,500 per child in the form of a tax refund.

In effect, the federal CTC has a trapezoid-like structure where some families are too poor to receive any credit, some fall within the phase-in range, some benefit from the full credit, some fall within the phase-out range, and some families earn too much to receive the credit.

Since its enactment in the late 1990s, the federal CTC has grown and changed. For instance, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) increased the credit from $1,000 to $2,000 per child through 2025, reshaped it to allow more affluent families to claim it and began excluding immigrant children without Social Security numbers.[4] Prior to the TCJA, all children whose parents met the income eligibility requirements, regardless of citizenship status, received the federal credit.

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) temporarily expanded the credit—for 2021 only—to $3,000 for older children and $3,600 for children under 5. It was also reformed to allow monthly credit payments rather than one annual lump sum. Most importantly, it was reworked to reach more children, including nearly one-third of children who live in families too poor to qualify for the credit under permanent law. In 2022, after the credit’s expansion expired, 45 percent of Black children, 42 percent of Hispanic children, and 23 percent of white children were no longer able to receive the full credit.[5] Current limits for lower-income families disproportionately leave out children of color.

The expanded version of the federal CTC in effect for 2021 was wildly successful in reducing child poverty, cutting it by 46 percent. It lifted 3.7 million children out of poverty before it was allowed to lapse in 2022.[6] Research has since shown that low and middle-income households overwhelmingly spent this boosted credit on housing, food, and clothing – a testament to how vital an expanded CTC is to helping families make ends meet each month.[7] In the absence of federal action to reinstate those reforms, state lawmakers are increasingly creating and expanding Child Tax Credits to boost income and opportunities for children and families in their states.

More States Adopting and Expanding Child Tax Credits

More and more lawmakers are adopting and expanding state Child Tax Credits. As we head into 2025, 15 states and the District of Columbia are providing Child Tax Credit benefits to families with children.

This year alone, lawmakers in three states and D.C. created or expanded CTCs. Colorado, New York, and Utah expanded their existing credits while D.C. passed its first Child Tax Credit.

In Colorado, lawmakers passed the Family Affordability Tax Credit which builds on the state’s existing CTC. In 2024, qualifying families will be eligible for an additional $3,200 per child under 6 and $2,400 per child ages 6 through 16, in addition to the state’s Child Tax Credit which only benefits children under 6. In future years, the tax credit’s availability and size will be contingent on state revenue growth.

Utah slightly expanded the age range for its nonrefundable CTC, now allowing families with 4-year-old children to qualify. New York authorized a temporary expansion of its Empire State Child Credit in 2024, boosting the credit for qualifying families by 25 to 100 percent depending on household income.[8]

Meanwhile, Minnesota made important strides towards periodic payments for its Child Tax Credit. Qualifying Minnesota families will soon be able to claim half of their prior year’s CTC as periodic payments in July through December and will receive the remainder of their credit with their tax return.[9]

These CTC improvements in 2024 were a continuation of the momentum on these credits in recent years. Since 2021, 12 states plus D.C. have either created or expanded a CTC.

While most states have created CTCs that are independent of the federal Child Tax Credit, two states – Oklahoma and New York – have credits directly tied to some version of the federal CTC.

While most states have created CTCs that are independent of the federal Child Tax Credit, two states – Oklahoma and New York – have credits directly tied to some version of the federal CTC.

Oklahoma offers families a choice between a nonrefundable credit worth 5 percent of the federal CTC or a nonrefundable credit worth 20 percent of the federal Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit. The state limits the credit to taxpayers with incomes under $100,000. This credit doesn’t fully reach families in or on the verge of poverty because it is nonrefundable, meaning it cannot be used by lower-income families who have little state income tax liability but pay substantial amounts of sales, excise, and property taxes.

New York has a refundable credit worth $100 per qualifying child or 33 percent of the taxpayer’s allowable federal credit, whichever is greater. Lawmakers in New York decoupled their state credit (the Empire State Child Credit) from changes to the federal CTC occurring after 2017, so they continue to maintain a maximum credit of $330 (that is, 33 percent of the $1,000 maximum federal credit in place before TCJA) along with other pre-TCJA tax parameters. The credit is available to children under the age of 17.

Other states—particularly Arizona and Idaho—have policies that resemble CTCs but are either far less robust or best thought of as state CTCs in name only.

Both Arizona and Idaho have nonrefundable dependent credits—meaning they can apply to more than just minor dependents such as permanently disabled adults. These replaced former dependent or personal exemptions. In practice, exemptions directly reduce taxpayer’s taxable income while a credit reduces tax liability. Generally, these credits would be stronger if they were available on top of existing dependent exemptions or if they were made substantially larger (and refundable, where applicable) to account for the lack of dependent exemptions in these states.

States Should Design Child Tax Credits with Equity in Mind

The lapse of 2021’s federal Child Tax Credit enhancements has inspired a string of state actions and should continue to do so going forward. In the absence of additional action by Congress, states have several options to strengthen economic security and child well-being through new or expanded CTCs. Lawmakers should design these state CTCs with an eye toward equity by ensuring that the credit reaches as many low- and moderate-income children as possible.

1. Ideally, lawmakers should create standalone refundable CTCs where children benefit regardless of their family’s employment or immigration status.

The advantage of implementing a credit separate from the federal CTC is that states can avoid the shortcomings of the federal credit (particularly the earnings requirement and lack of full refundability) that keep many lower-income families from receiving the full benefit. Instead, states can use the flexibility they have to determine the scope and scale of their credits without these restrictions.

That flexibility allows state lawmakers to:

- Make the credit fully refundable. Refundability is key to the CTC’s success. If a credit is refundable, taxpayers receive a refund for the portion of the credit that exceeds their income tax bill. Refundable credits help offset all taxes paid, not just income taxes, helping mitigate some of the regressive effects of state and local sales, excise, and property taxes.

- Avoid an earnings requirement. Earnings requirements mean that families with lower earnings get a smaller credit or no credit at all, paradoxically excluding the kids with the greatest needs from a policy meant to help children.

- Avoid restrictions based on immigration status. Under changes to federal law signed at the end of 2017, children without Social Security numbers are now excluded from accessing the federal CTC. Most states have wisely chosen to adopt a more inclusive posture and make their CTCs available to all children whose parents meet income eligibility requirements, regardless of citizenship status.[10]

- Set a maximum amount per child, rather than per household, to not penalize children in larger families. Lawmakers should also provide a more robust credit to younger children in their formative years when families confront significant expenses and caregiving responsibilities that additional financial resources can help address.

- Set state-specific phase-out ranges that can better target the credit to low- and middle-income families. Setting a lower phase-out range enables the state credit to reach families in need while dramatically reducing the cost to state budgets. If lawmakers are most interested in poverty reduction, an administratively simple approach for states with Earned Income Tax Credits could be to mirror EITC phase-outs, creating a tightly targeted state CTC.[11]

- Index the credit to inflation so that it does not erode over time. Whether and how policies are indexed for inflation has major implications for their power to improve economic well-being and reduce poverty over the long run.[12]

- Make the credit available on an advanced or monthly basis. Research shows that monthly cash payments reduce poverty and keep it lower year-round.[13] This provides families flexibility to meet financial needs in real-time and prevent the accumulation of debt.

2. If unable to create a standalone credit, lawmakers could enact a CTC as a percentage of the federal credit in combination with a minimum credit.

States can piggyback CTCs on top of federal rules at a flat percentage rate, as many do with their EITCs. For example, a state CTC calculated as 10 percent of the federal CTC would amount to a $200 state credit for any child who receives it in full. This offers a relatively simple template for states but has significant drawbacks including the relatively high income thresholds for eligibility, the exclusion of immigrant children, and the lack of inflation indexing. In addition, the future design of the federal CTC remains uncertain as its fate is wrapped up in the broader debate over a slate of federal tax provisions set to expire at the end of 2025.

The worst feature of the federal CTC is that children in many families are deemed too poor to receive the full benefit. Even if state lawmakers choose to conform to the federal CTC broadly, they should take care not to amplify this inequity and should establish a minimum, refundable benefit for lower-income families.

3. Lawmakers could also opt to fill the gap for children left behind by the federal CTC.

State lawmakers can make up for the main shortcoming of the federal CTC by ensuring that children in families too poor to receive the full credit are brought up to the full $2,000 amount, or to some portion of that amount. This ensures that a state’s lowest-income children are not left behind. Of these three options, this is the most carefully tailored to reach only those families in the most vulnerable economic circumstances. As a result of its narrower reach, this option could also cost less than the other proposals, which may be appealing to some lawmakers concerned about the budgetary impact of more expansive CTC proposals.

Under any of these options, states should explore advanced or monthly payments in addition to annual payments. Recent federal experience suggests that this approach can play a role in meaningfully reducing child poverty, improving economic security, and enhancing families’ ability to meet their basic needs.[14]

APPENDICES

- APPENDIX A: Refundable State Child Tax Credits, 2025

- APPENDIX B: Nonrefundable State Child Tax Credits, 2025

Endnotes

[1] Sophie, Collyer, Megan Curran, Aidan Davis, David Harris, and Christopher Wimer. State Child Tax Credits and Child Poverty: A 50-State Analysis. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University, November 2022.

[2] Waxman, Samantha, et al., Income Support Associated With Improved Health Outcomes for Children, Many Studies Show. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 27, 2021. Hardy, Bradley L., Child Tax Credit Has a Critical Role in Helping Families Maintain Economic Stability. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 14, 2022.

[3] Davis, Carl and Marco Guzman. State Income Taxes and Racial Equity: Narrowing Racial Income and Wealth Gaps with State Personal Income Taxes. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 4, 2021.

[4] Guzman, Marco. “Inclusive Child Tax Credit Reform Would Restore Benefit to 1 Million Young ‘Dreamers’.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. April 27, 2021.

[5] Hughes, Joe and Emma Sifre. “Expanding the Child Tax Credit Would Advance Racial Equity in the Tax Code,” August 29, 2023. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

[6] Parolin, Zachary, et al. Absence of Monthly Child Tax Credit Leads to 3.7 Million More Children in Poverty in January 2022. Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University, February 17, 2022.

[7] Schild, Jake, et al. Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Household Spending: Estimates based on U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey Data. National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2023.

[8] Butkus, Neva. “Which States Improved Child Tax Credits and EITCs in 2024?” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 25, 2024.

[9] Madden, Nan. “Advance periodic payments would make the Minnesota Child Tax Credit fit even better into family budgets,” Minnesota Budget Project, May 7, 2024.

[10] Guzman, Marco, and Emma Sifre. “Improving Refundable Tax Credits by Making Them Immigrant-Inclusive,” Pittsburgh Tax Review. Volume 21, Number 2. July 2024.

[11] Butkus, Neva and Aidan Davis. “Boosting Incomes, Improving Tax Equity: State Earned Income Tax Credits in 2023.” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2023.

[12] Collyer, Sophie, et al., Keeping up with Inflation: How Policy Indexation Can Enhance Poverty Reduction. The Century Foundation, August 25, 2022; and Grundman O’Neill, Dylan. Indexing Income Taxes for Inflation: Why It Matters. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, August 22, 2016.

[13] Parolin, Zachary, Elizabeth Ananat, Sophie Collyer, Megan Curran, and Christopher Wimer. 2023. “The Effects of the Monthly and Lump-Sum Child Tax Credit Payments on Food and Housing Hardship.” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 113: 406-12.

[14] Hamilton, Christal, et. al. Monthly Cash Payments Reduce Spells of Poverty Across the Year. Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University, May 9, 2022.