Impacts of the Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act

briefThe Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act passed by the House of Representatives on January 31 is a compromise between lawmakers who want to address child poverty and lawmakers who want to expand the Trump tax cuts for corporations and therefore includes provisions that do both.

It also offsets the costs of those provisions by barring new retroactive claims (many of which are likely to be fraudulent) of a tax credit that was enacted to encourage companies to maintain employment during the pandemic.

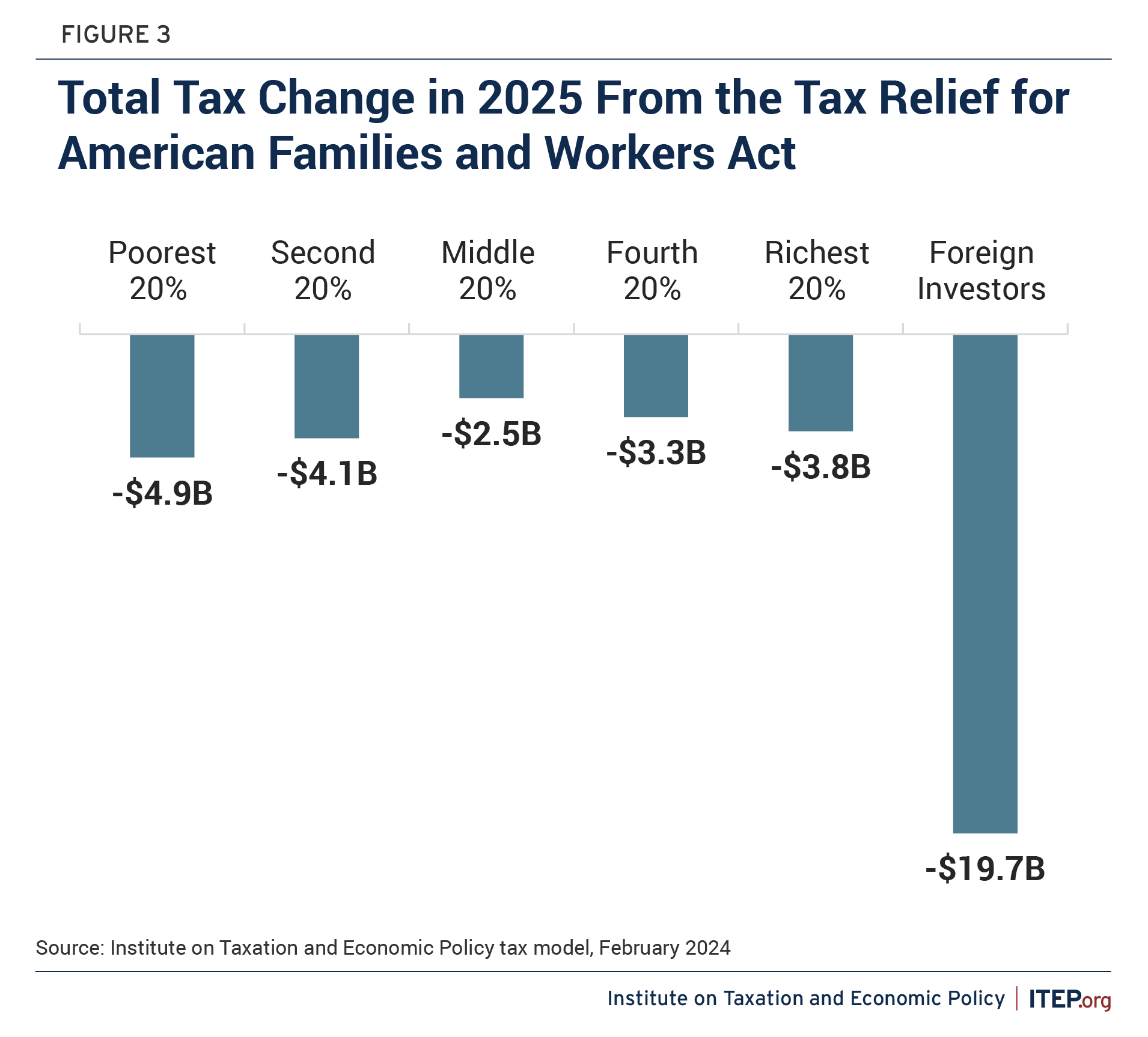

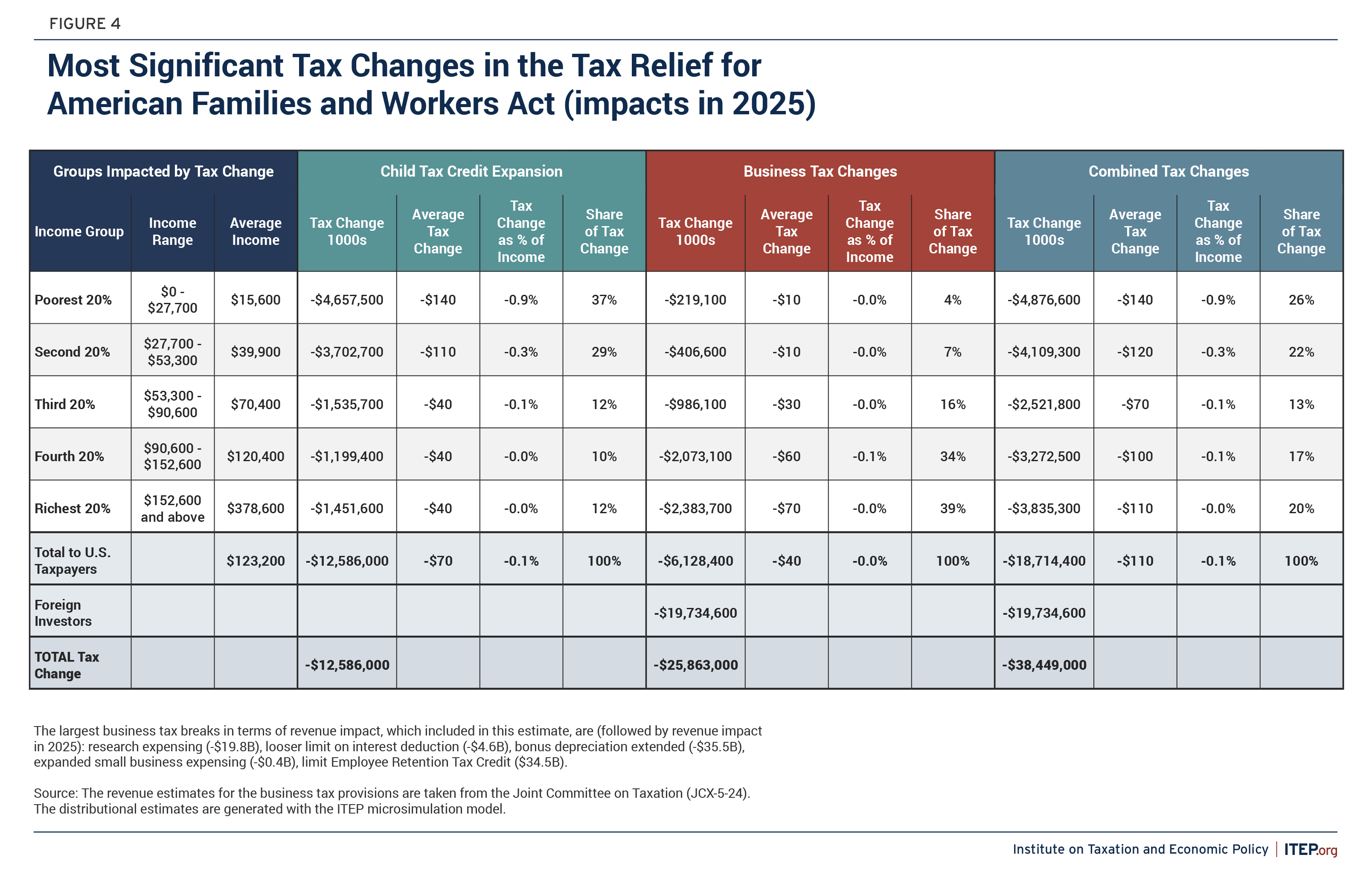

The net result of the bill is significant benefits for families among the poorest 40 percent of Americans, but also sizable benefits for many well-off Americans who own shares in corporations or own other types of business assets. It also provides benefits to foreign investors in American corporations receiving the business tax breaks in the legislation.

Key Findings:

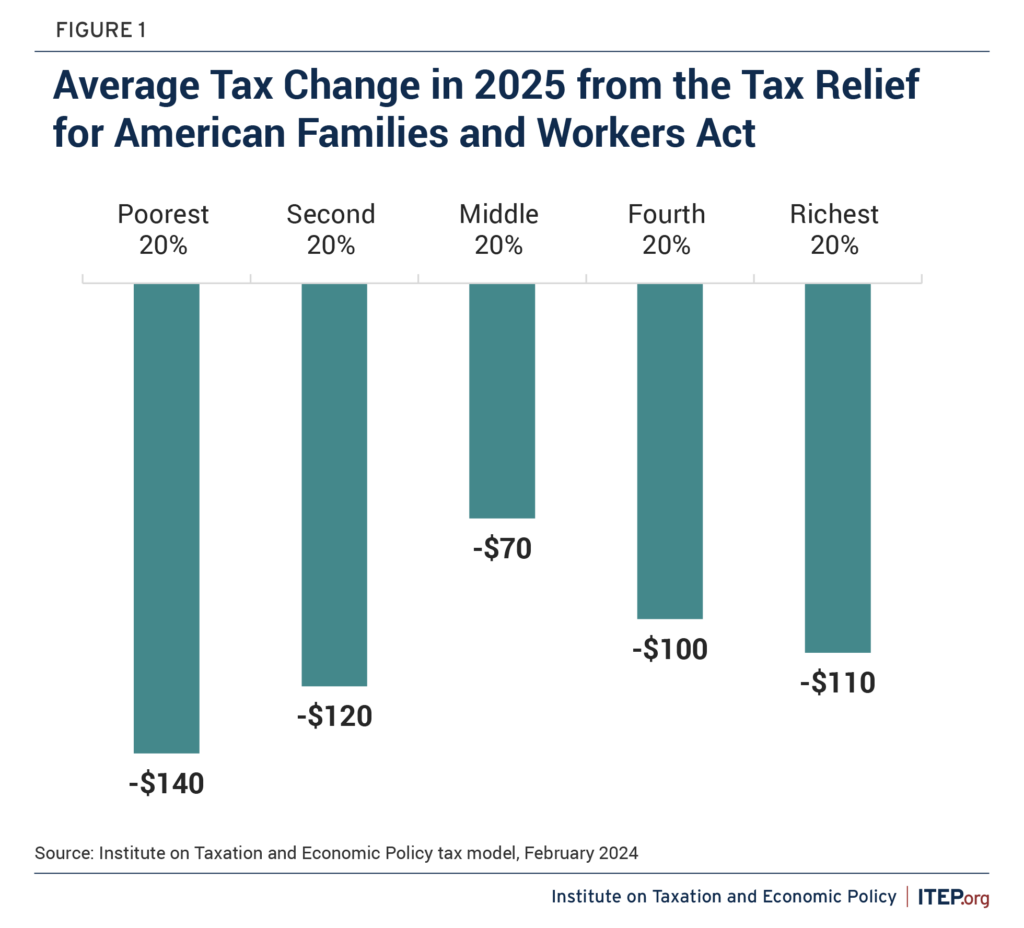

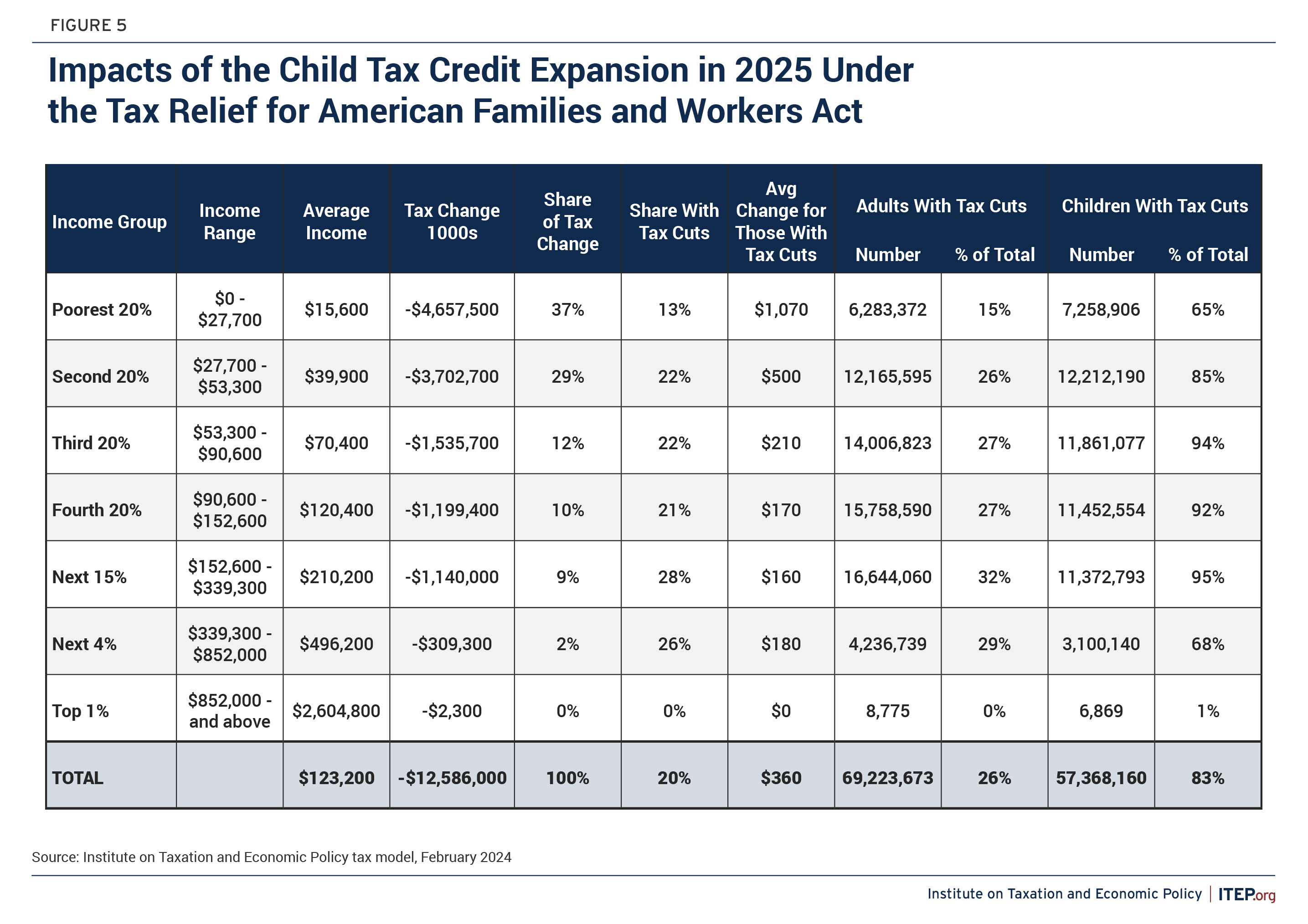

- In 2025, the year when the bill’s provisions are fully in effect, the poorest fifth of taxpayers would receive a net tax cut averaging $140 a year while the richest fifth of taxpayers would receive a net tax cut averaging $110.

- The legislation is “paid for,” meaning its tax cuts are offset with its revenue-raising provision over a decade, but the bill overall raises revenue in certain years and loses revenue in certain years. This analysis focuses on the year 2025 when its net impact would be a cut in revenue and a tax cut on average for all income groups.

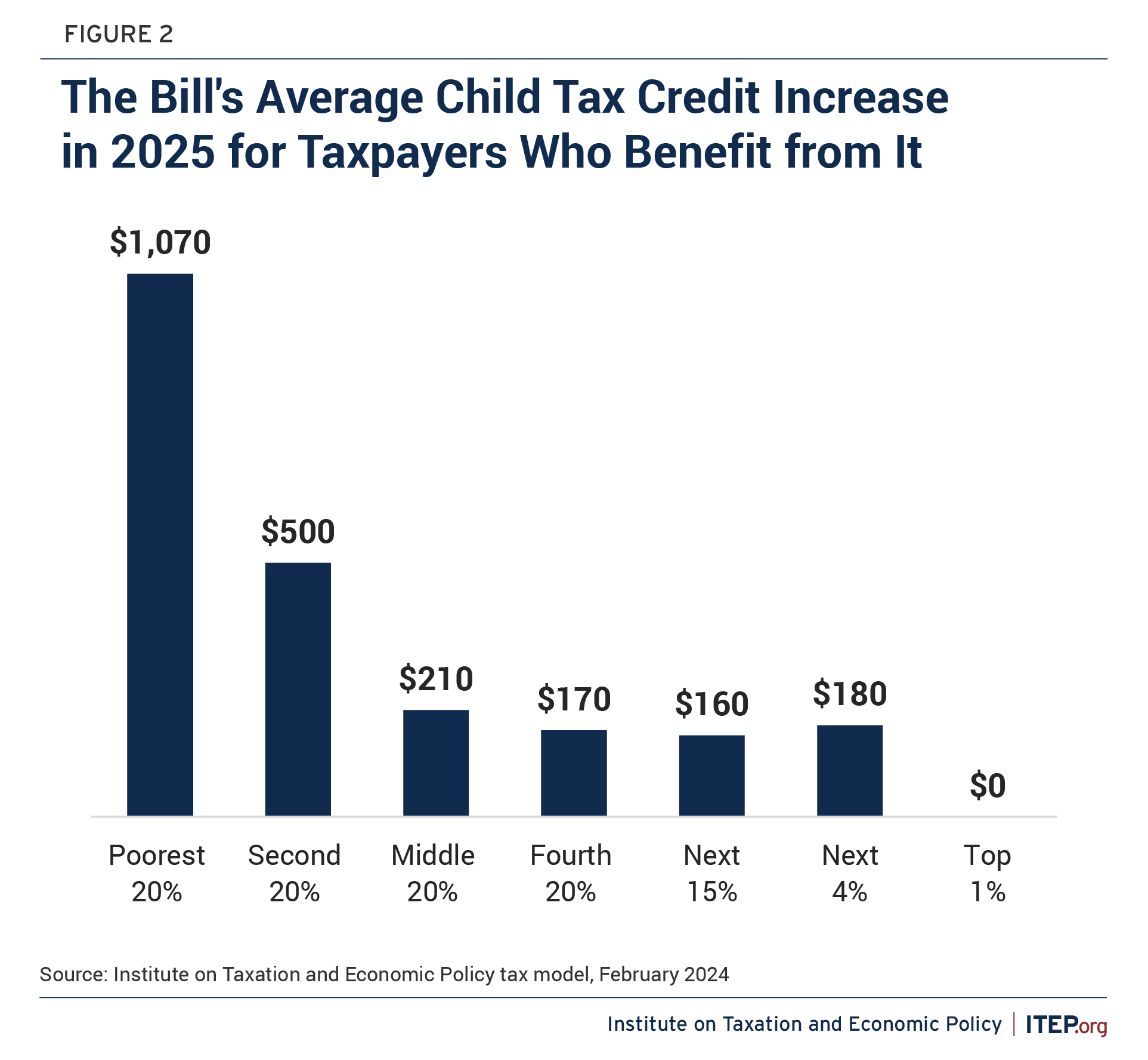

- The impact on certain taxpayers can be much more dramatic, particularly for families with children and modest incomes. Families among the bottom 20 percent of taxpayers who have children qualifying for the bill’s Child Tax Credit provisions would receive an average of $1,070 from them.

- The Child Tax Credit provisions are targeted largely to families who are limited from receiving the full CTC under current law, particularly those with more than one child. These provisions address, at least partly, some problematic features of the current CTC rules.

- The legislation would also provide benefits to foreign investors in American corporations because they benefit from the bill’s business tax cuts but they are not affected by the bill’s revenue-raising provision, which generally only affects business owners who are U.S. citizens or U.S. residents.

A Compromise with Tax Cuts for Children and Tax Cuts for Businesses – But Also a Tax Increase for the Rich

The Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act is often discussed as a compromise between those who want to address child poverty (by relaxing rules that unfairly limit the Child Tax Credit for poor children) and those who want to expand the Trump tax cuts for corporations (by removing the few limits on business tax breaks included in the 2017 tax law).

It also offsets the costs of these provisions, and the resulting tax increase from the offset would likely fall on many of the well-off people who own businesses and receive most of the business income in the United States.

This revenue-raising provision would bar taxpayers from making any more retroactive claims on the Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC), which was designed to encourage companies to maintain employment in 2020 and 2021. According to the IRS and numerous media reports, many, if not most, of the claims made for the ERTC at this point are fraudulent. They are often the result of unscrupulous third parties falsely telling business owners that they are eligible for the credit. In other cases, the claims are made on behalf of shell companies that are not eligible because they do not employ anyone.[1]

Improvements in the Child Tax Credit

The bill leaves in place overly strict earnings requirements that apply only to poor families. A well-off family living on investments or a trust fund and doing no work whatsoever can receive the full Child Tax Credit (CTC). But the part of the credit that helps families too poor to have much income tax liability (the refundable portion of the credit) is limited to a fraction of their earnings above $2,500.

This bill does not change that. It does, however, make these rules a little more generous to millions of children and families currently receiving little or nothing, particularly, families with more than one child. Under current law, a family with several children often receives a smaller credit per child than a family with the same earnings but only one child. This legislation would fix that flaw by phasing in the credit for each child separately, ensuring families at the same income level get roughly the same credit per child.

The bill would also eventually remove the rule that limits the refundable portion of the credit to a smaller amount than the full credit that better-off families receive. Currently, the refundable amount is capped at $1,700 per child compared to $2,000 for the non-refundable portion. This proposal would increase the refundable portion to $1,800 in 2023, $1,900 in 2024, and the full $2,000 credit in 2025.

The third and final change in the CTC that is included in this analysis is the provision of the bill that would, for the first time, index the total credit amount (along with the maximum refundable credit) to inflation, which would increase it from $2,000 to $2,100 in 2025.

The bill includes another reform that is not included in these estimates, a “lookback rule” allowing families to use their earnings from the prior year to calculate their credit if they exceed the family’s earnings in the current year. This lookback option would help even more of the children currently not receiving the full credit, but it is not included in our analysis.

Business Tax Cuts

The bill provides something that has long been sought by corporate lobbyists – language retroactively calling off the few cost-containing business tax provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (the Trump tax law). When the law was enacted back in 2017, drafters presented these provisions as partly offsetting that legislation’s tax cuts and restricting its overall cost to $1.5 trillion over a decade (later updated to $1.9 trillion over a decade).

Two of these cost-containing provisions in the 2017 law, a stricter rule for deducting research and development expenses and a tighter limit on deductions for interest payments made by companies, took effect in 2022 as scheduled.

Another, the gradual phase-out of the bonus deprecation that had been allowed under the 2017 law, began in 2023 as scheduled.

The Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act would retroactively call off these cost-containing features of the Trump tax law and delay them from going into effect until after 2025.

The following is more detail on the significant business tax cuts in the bill.

Research expensing

2025 Revenue Impact: -$19.8 billion

This tax break is supposedly an incentive for corporations to conduct research that benefits society, but lawmakers have not asked what it has accomplished.

- Some activities subsidized by this tax break do not meet any definition of “research” that most people would understand. Companies urging Congress to extend this tax break range from a brewery and a company that develops frozen and packaged foods to a sausage business and a company that develops electronic games for casinos. Lawmakers should ask what “research” this tax break supports before blindly extending it.

- Many of the companies lobbying for this tax break have paid very little in taxes. Netflix, for example, has paid federal corporate income taxes equal to less than 1 percent of its reported profits over four years.

- Read more about research expensing here.

Bonus depreciation

2025 Revenue Impact: -$35.5 billion

This tax break allows companies to deduct the cost of equipment the year they purchase it, rather than deducting the cost over several years until the equipment wears out. This extreme version of accelerated depreciation raises several problems.

- Accelerated depreciation has let many large corporations (Verizon, Amazon, Walt Disney, Con Edison, General Motors, Dish Network, and others) largely avoid taxes, particularly during the last several years when this bonus depreciation provision has been in effect.

- Bonus depreciation is supposed to encourage investment, but research shows that corporate leaders pay little attention to depreciation tax breaks when making investment decisions, even though their tax departments naturally exploit them to the greatest extent possible.

- Read more about bonus depreciation here.

Looser limit on deductions for interest payments

2025 Revenue Impact: -$4.6 billion

This provision would overturn a stricter limit on deductions that businesses take for interest payments they make on their debt and would extend the more lenient rule that was in effect until 2022.

- Without strict limits, the tax deduction for interest payments results in the tax code favoring corporations that borrow money over corporations that raise funds from investors by selling shares.

- This provides an unwarranted subsidy to private equity firms that buy businesses and load them up with debt, which often results in the companies spiraling into bankruptcy.

- In recent years this practice has led to the collapse of Toys “R” Us, Payless and other well-established companies.

- Read more about the looser limit on interest deductions here.

Expanded small business expensing

2025 Revenue Impact: -$400 million

This provision, raising the limits on investment that can be deducted immediately under section 179 of the tax code, is more or less bonus depreciation but limited to relatively smaller companies.

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act allowed business owners to fully expense up to $1 million in investments in equipment (up from $500,000 previously) if they invest less than $2.5 million a year (up from $2 million previously).

- These amounts were indexed for inflation so that in 2023 business owners could fully expense up to $1.16 million if they invest less than $2.89 million.

- These rules are already generous enough to benefit companies that most Americans think of as “small businesses.”

- This legislation would increase those limits slightly starting in 2024 to $1.29 million and $3.22 million.

Technical Details on How Corporations and Other Businesses Are Affected by Certain Provisions

The provision that raises revenue, the bar on new claims for the ERTC, affects businesses that would otherwise claim it. Some of these are real businesses, and some of them are shell companies that serve no legitimate purpose but are created by those with the means to engage in such schemes.

These businesses are not likely to be large corporations, which have enough accounting expertise to have already claimed any portion of this credit for which they were eligible and are unlikely to take the risk of committing obvious crimes by claiming it when they are clearly not eligible.

We therefore assume that the tax increase resulting from this provision would have an effect similar to any tax change for “pass-through” businesses. Pass-throughs are business entities that do not pay the corporate income tax because their profits are included on the personal income tax returns of their owners. Tax changes for pass-throughs mostly affect the richest fifth of Americans, mainly because they receive most of the pass-through business income.

The bill’s provisions that cut taxes for businesses are different. Unlike the revenue-raising provision, the provisions that cut taxes for businesses largely affect C corporations, which are the specific type of corporations that pay the federal corporate income tax.[2]

Pass-through businesses are not likely to be foreign-owned to any significant degree. (One of the most prominent types of pass-through entities, the S corporation, cannot be owned by anyone who is not either a U.S. citizen or U.S. resident.) Tax measures that affect pass-through business entities, such as the revenue-raising provision in this bill, are not likely to have any significant effect on foreign investors.

But foreign investors do own a significant share of American C corporations and therefore benefit from corporate tax cuts. Congress’ official revenue estimators at the Joint Committee on Taxation therefore assume that a portion of the benefits from a corporate tax cut flows to foreign investors.[3]

Recent research has concluded that foreign investors own 40 percent of stocks in C corporations and would therefore receive a significant share of the benefits from corporate tax cuts.[4]

As result, well-off Americans can be affected by the bill’s tax cuts (which affect pass-through businesses and C corporations) as well as the bill’s tax increase (which affects pass-through businesses but not C corporations). The net benefits for well-off Americans are therefore more restrained than they might otherwise be when it comes to legislation that cuts taxes for businesses.

But foreign investors can only be affected by the bill’s tax cuts, not the bill’s tax increase because the latter only affects pass-through businesses. This helps explain why the estimated benefits for foreign investors seem so large relative to the benefits for Americans.

[1] United State Treasury, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, “FinCEN Alert on COVID-19 Employee Retention Credit Fraud,” FIN-2023-Alert007, November 22, 2023. https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FinCEN_ERC_Fraud_Alert_FINAL508.pdf

[2] This analysis takes each business tax cut and determines what portion flows to C corporations and what portion flows to pass-through entities, based on the tax expenditure estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). For example, JCT finds that 95 percent of the research and development expensing break goes to C corporations and only 5 percent goes to pass-through businesses, which we incorporate into our analysis.

[3] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Modeling the Distribution of Taxes on Business Income,” October 16, 2013, JCX-14-13. https://www.jct.gov/publications/2013/jcx-14-13/

[4] Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” Tax Policy Center, October 27, 2020. https://www.law.nyu.edu