The Estate Tax is Irrelevant to More Than 99 Percent of Americans

reportKey findings

• The tax law enacted under President Donald Trump has reduced the reach of the federal estate tax to historic lows. In 2019, the most recent year for which data are available, only 8 of every 10,000 people who died left an estate large enough to trigger the tax.

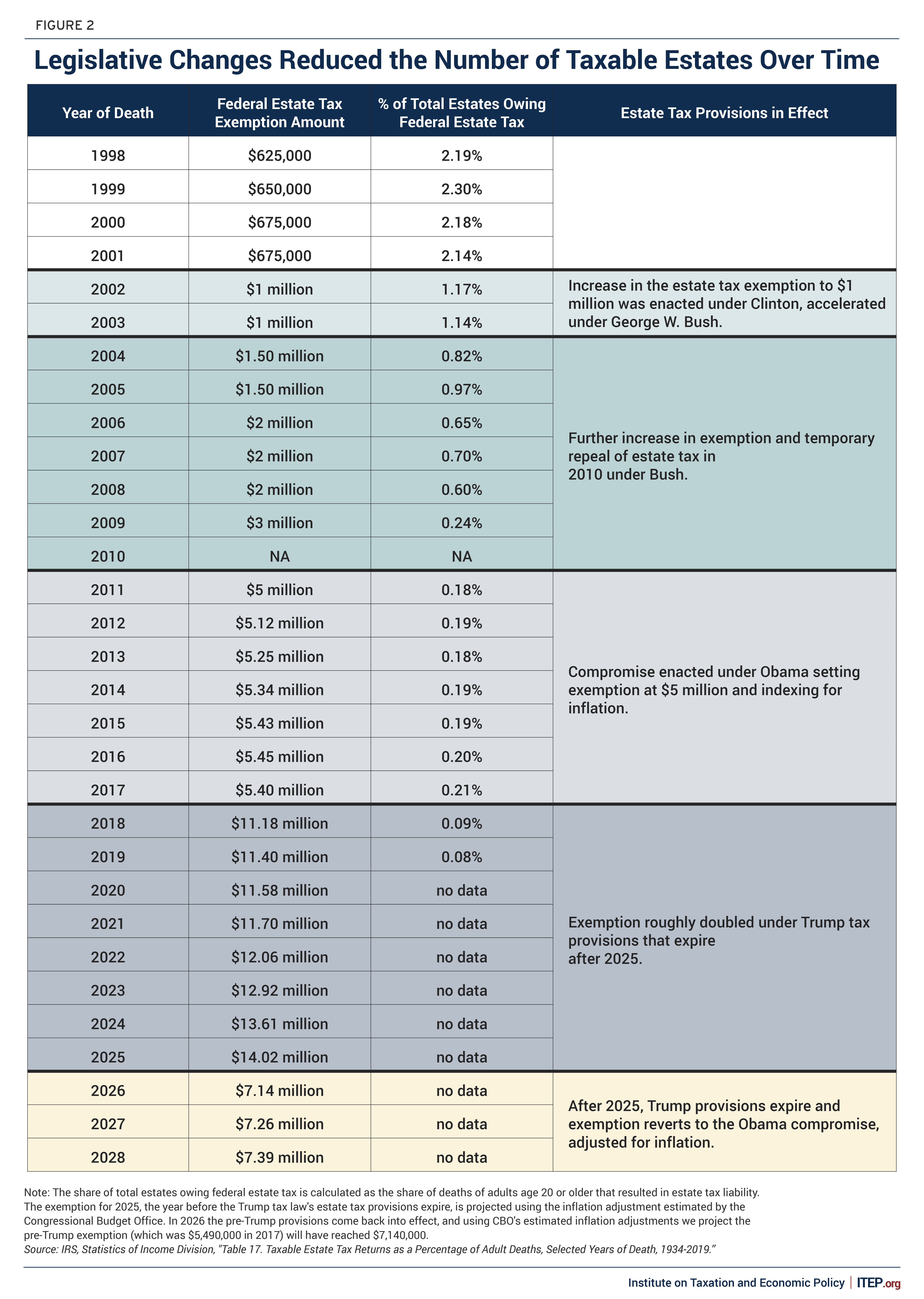

• Legislative changes under presidents of both parties have increased the basic exemption from the estate tax over the past 20 years. This has cut the share of adults leaving behind taxable estates down from more than 2 percent to well under 1 percent.

• Historical data on the share of estates taxed each year demonstrate that less than 1 percent of adults would leave behind taxable estates under any proposal before Congress.

• While the federal estate tax rate is currently 40 percent and has, at times, been higher than 50 percent, the share of estate assets going towards the tax is almost always much lower and has averaged around 20 percent in recent years.

• Most of the estate tax is paid by estates worth more than $20 million; in recent years the majority has been paid by estates worth more than $50 million.

• Contrary to one criticism of it, the estate tax does not result in “double taxation,” and, in fact, much of the assets subject to the tax are unrealized capital gains, income that would escape taxation forever if not for the estate tax.

• Several tax provisions, including the federal gift tax and several rules related to trusts, are designed to prevent people from avoiding the federal estate tax, but they are rife with loopholes that further reduce the reach of the tax and which Congress can address legislatively.

The Reach of the Estate Tax Is at a Historic Low

The federal estate tax is one way that Congress decided, over a century ago, to ensure that families passing massive fortunes down through generations contribute to finance the public investments that made those fortunes possible.

Families lucky enough to accumulate enormous wealth are the greatest beneficiaries of the public investments we all finance through taxes. The wealthiest Americans acquired their position because their corporations use public roads to ship goods, their companies employ the workforce created by our public education system, their customers buy products derived from government-funded research, and their investments are possible because of the courts that define property rights and the public safety personnel who enforce those rights.

All Americans benefit from these public investments, but it is beyond doubt that Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Michael Bloomberg, and other billionaires have benefited more than others. The federal estate tax is one part of our tax system that provides a mild corrective to this imbalance and to the economic inequality that has rocketed upwards over the past several decades.[1]

And yet today the estate tax is the weakest it has been in its century-plus history. Policy changes enacted under presidents of both parties have cut down the reach of the estate tax, but the current provisions – part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act signed into law in 2017 by President Trump – have weakened the tax more than ever.

In 2019, the most recent year for which data are available, only 8 of every 10,000 people who died left an estate large enough to trigger the tax. This is the lowest share of estates affected by the tax shown in all the annual data provided by the IRS (with the exception of 2010, when the estate tax was effectively temporarily repealed).

The Estate Tax Exemption Has Risen Substantially Over the Past 20 Years

The federal estate tax has long been America’s most misunderstood revenue source. A 2017 poll found that 63 percent of respondents believed the estate tax primarily affected poor and middle-class families, which could not be further from the truth.[2]

Everyone leaves behind an estate, even if a small one, when they die. For the past 20 years, more than 99 percent of these estates have gone untaxed.

The most important policy determining the number of taxable estates each year is the size of the basic estate tax exemption. President Bill Clinton signed legislation that would have raised the estate tax’s basic exemption to $1 million (effectively $2 million for married couples), and this was accelerated by legislation enacted under President George W. Bush that went into effect in 2002. That year, the percentage of deaths resulting in federal estate tax liability was cut in about half, dropping from about 2 percent to around 1 percent. As the Bush tax cuts phased in over the following years, the share of estates taxed fell below 1 percent and has stayed there ever since.

The Bush tax cuts gradually increased the exemptions and gradually shrank the estate tax through 2009 and then more or less repealed it for 2010. But all these new estate tax provisions were scheduled to expire at the end of 2010.

President Obama compromised with Republicans who controlled Congress and eventually made parts of the Bush tax cuts permanent. The resulting law set the estate tax exemption at $5 million per spouse, which was set to increase each year with inflation.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed into law by President Trump, effectively doubled that exemption to more than $11 million starting in 2018 and, again, set it to increase with inflation. In 2024, the exemption will be $13.61 million per spouse.

For most large estates, the portion shielded from the tax is even larger than the basic exemption because of other special provisions. Most prominently, assets bequeathed to charity are not subject to the tax. For example, consider a never-married individual who died in 2019 leaving behind $20 million, $4 million of which is left to charity. The basic estate tax exemption ensures that the first $11.4 million will be untaxed. The $4 million charitable bequest is also untaxed. With $15.4 million of the estate untaxed, just $4.6 million is subject to the tax. (And possibly less, depending on other circumstances.)

Less Than 1 Percent of Adults Would Leave Taxable Estates Under Any Proposal Before Congress

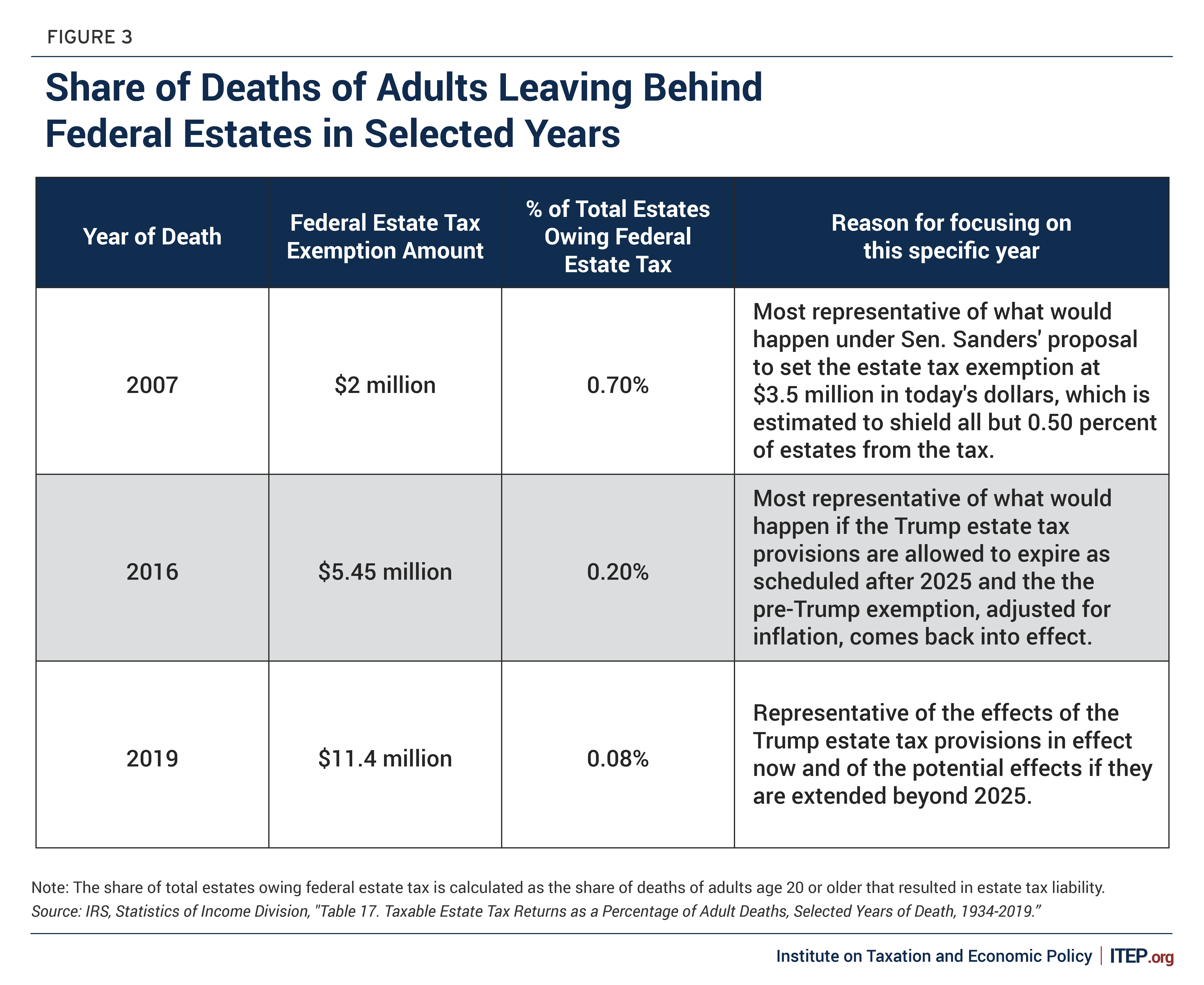

The IRS provides detailed information about the estate tax for selected years, and the data for some years is representative of what would happen under different proposals to modify the estate tax.

For example, the most recent data, for 2019, illustrates the effects of the large exemptions enacted as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Like many other parts of that law, the estate tax provisions will expire after 2025. If lawmakers make those provisions permanent as Congressional Republicans propose, one can expect the share of estates subject to the tax to remain close to the level shown for 2019, when only 0.08 percent of estates were taxed.[3]

If Congress does nothing, the exemption will return to the level set by President Obama when he compromised with Congressional Republicans ($5 million in 2011, adjusted for inflation each year thereafter). One could then expect the share of estates subject to the tax to remain close to the level shown for 2016, one of the years when the Obama-era exemption applied. In 2016, just 0.20 percent of adults who died left an estate large enough to be taxed. That is just 20 out of every 10,000 estates subject to the federal estate tax.

The most dramatic expansion of the estate tax that has been introduced in Congress is that of Sen. Bernie Sanders, who would set the exemption at $3.5 million per spouse. The data that is most representative of the potential effects of this proposal is the IRS data for 2007. The exemption that year was $2 million per spouse, but if it had been adjusted for inflation it would reach $3.1 million by 2026, when the temporary Trump provisions expire. One study estimates that under the Sanders proposal the estate tax would reach 0.5 percent of estates, which is a little lower than the 0.70 percent of estates (70 of every 10,000 estates) that were taxed in 2007.[4]

Even in 2007 the share of estates in each state subject to the tax was less than 1 percent in all but a few places as illustrated below (California, the District of Columbia, Florida, and Maryland being the exceptions). The share of estates subject to the tax in 2007 ranged from a low of 0.18 percent in North Dakota to a high of 1.43 percent in California and 1.80 percent in the District of Columbia.

Because the figures for 2007 are likely to be roughly representative of the impact under Senator Sanders’ estate tax proposal, they likely show the maximum effect in each state going forward under any conceivable policy.

The Share of Estate Assets Going to the Estate Tax Has Averaged Around 20 Percent in Recent Years

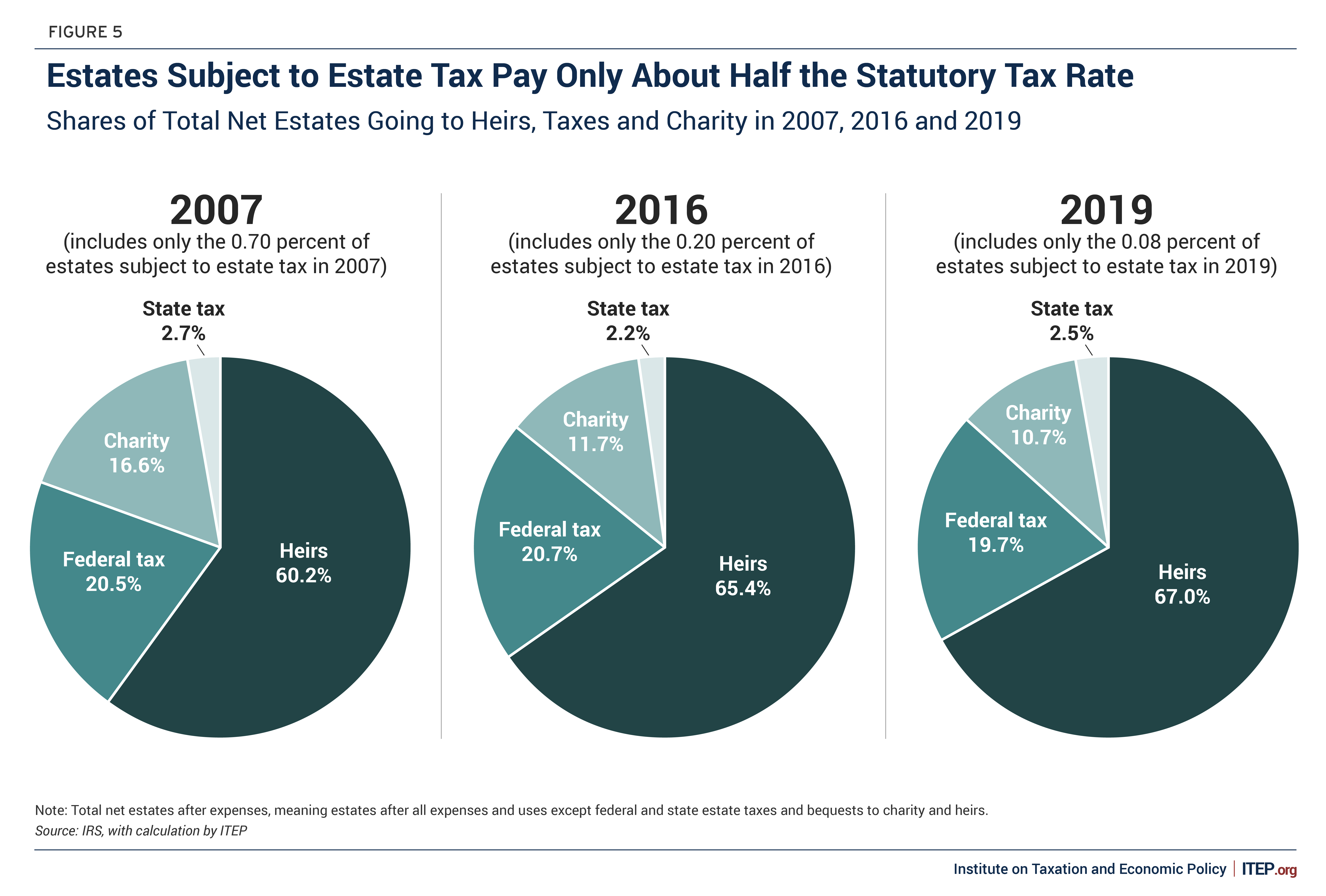

While the federal estate tax rate is currently 40 percent and has, at times, been higher than 50 percent, the share of estate assets going towards the tax is almost always much lower and has averaged around 20 percent in recent years.

Once it is determined that an estate will be subject to the tax, the next question is how much of it will go towards the tax. This is affected by the basic exemption, other estate tax breaks available, and the estate tax rate. The rate has varied over the years, with the Bush tax cuts gradually reducing it until lawmakers settled on a rate of 40 percent.

This does not mean that 40 percent of anyone’s estate goes towards the tax. The effective estate tax rate (the share of the estate going towards the tax) is almost always far smaller.

In the example above, the individual left behind $20 million but only $4.6 million of it is subject to tax. Assuming no other tax breaks apply, the tax would be assessed at 40 percent of $4.6 million, which comes to $1.84 million, or about 9 percent of the $20 million estate. In other words, while the statutory estate tax rate is 40 percent, the effective tax rate in this example is just 9 percent.

Even for those very few estates that are taxed, the vast majority of assets go to heirs and another significant portion goes towards charity. Only around a fifth goes towards the federal estate tax, and a much smaller portion goes towards state taxes.

Even when the estate tax was stronger and had a slightly wider reach, as was the case in 2007, the effective tax rate for estates subject to the tax was about the same, around 20 percent.

One proposal that would likely raise effective estate tax rates somewhat – at least for the very largest estates – is the aforementioned legislation introduced by Sen. Bernie Sanders. Under it, the estate tax would have several brackets, starting with a 45 percent rate for the portion of a taxable estate between $3.5 million and $10 million, with marginal rates rising with the size of the estate until reaching a rate of 65 percent for the portion of a taxable estate exceeding $1 billion.[5]

But as is the case under current law, these rates would be statutory rates, not effective rates. Even estates worth more than $1 billion would have a far lower effective rate once exemptions, charitable bequests, and the lower rates applied to the first $1 billion of the estate were all taken into account.

Most of the Estate Tax is Paid by the Largest Estates

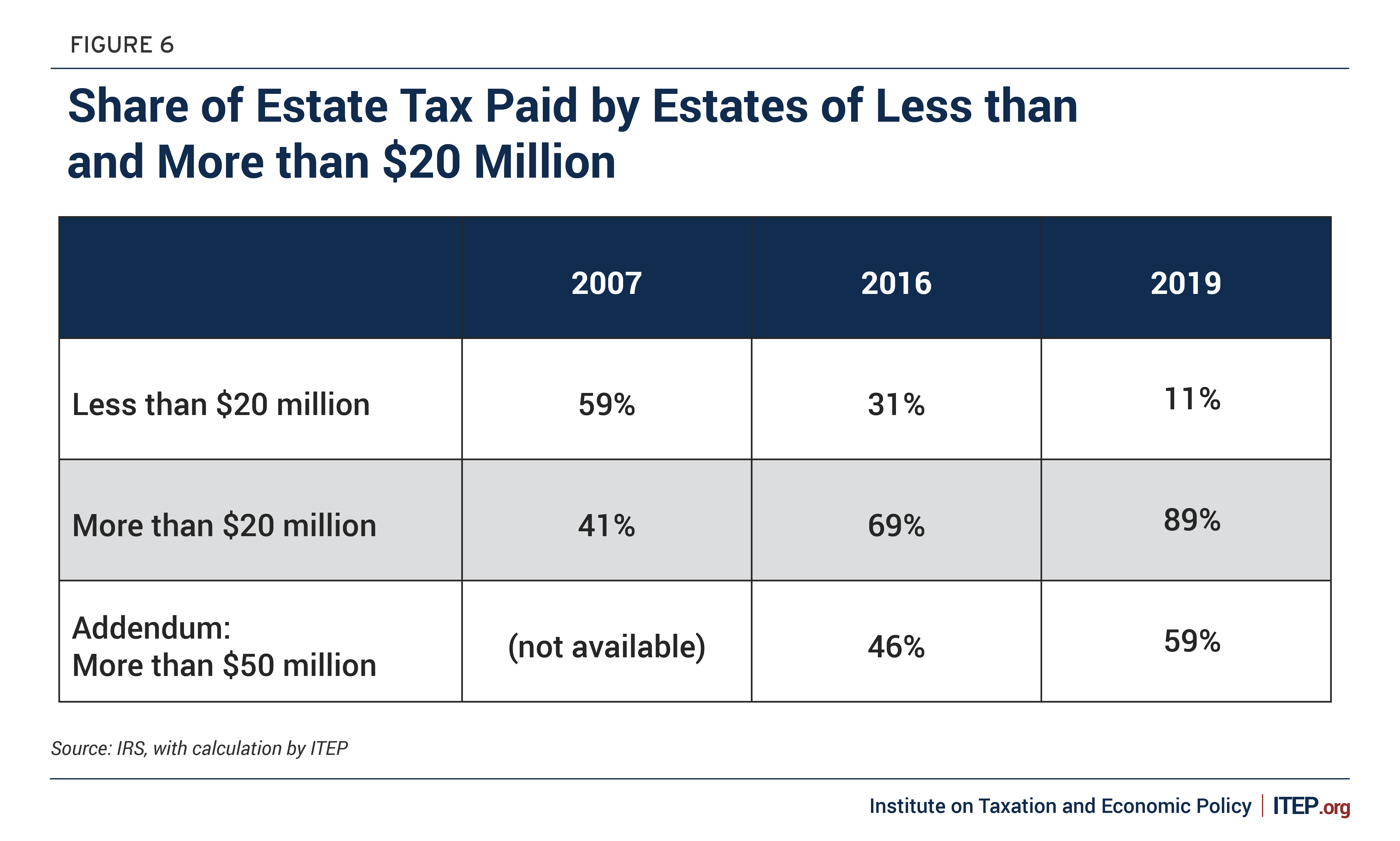

More than 99 percent of estates have gone untaxed in all three years examined in this report, because most estates are worth far less than the basic exemption. Even estates that exceed the basic exemption are not necessarily taxed very much. In fact, most of the tax is paid by estates that are much larger than the exemption.

In 2007, 2016, and 2019, at least 40 percent of the estate tax has been paid by estates worth more than $20 million. And in 2016 and 2019, nearly half and more than half, respectively, was paid by estates worth more than $50 million.

The Estate Tax is Sometimes Misunderstood as Double Taxation

Some critics of the estate tax suggest it is unfair because it represents a second tax on income that was already taxed when it was earned. But this is wrong for several reasons.

First, much of the value of the largest estates is unrealized capital gains, which have not been taxed and will not be subject to any tax other than the estate tax upon an individual’s death. ITEP previously estimated that among U.S. families with a net worth greater than $30 million, 43 percent of their wealth is unrealized capital gains.[6]

If an individual’s assets increase in value, that appreciation is income in an economic sense, but the tax code considers it income only when the individual sells the asset and realizes the capital gain as a profit, which is included in taxable income. But when appreciated assets are left to heirs, the unrealized capital gains accumulated up to that point escape the personal income tax forever because of a tax break called the “stepped-up basis.”[7] The estate tax is the only tax that might touch these unrealized capital gains on assets left to heirs.

Even for estates that include little or no unrealized capital gains, the argument that the estate tax results in double taxation is illogical and not how we conceptualize other taxes. When an individual earns income, they pay tax on the income, and then invest or spend their after-tax income. When they pay that after-tax income to a second individual to perform a service, it becomes income to the second person and is taxed. Everyone intuitively understands that money (or some other form of income) has moved from one person the next and that this justifies the imposition of a tax. Something similar is true of the estate tax, which only applies when assets are being transferred from one person (the decedent) to another (the heir).

Congress Should Close Estate and Gift Tax Loopholes

Individuals who make large gifts to others (usually family members) can be subject to the federal gift tax. Without a gift tax, wealthy families could easily avoid the estate tax by simply giving their assets to their heirs before they die. In 2023, the first $17,000 in gifts made by an individual to any one person (twice that amount for gifts made by a married couple) is excluded from the federal gift tax. (This gift tax exclusion is inflation-adjusted annually.) For example, an individual could give up to $17,000 to each of 10 grandchildren in 2023 and no gift tax would apply.

Any gifts made beyond the excluded amounts can also escape the gift tax, because the basic estate tax exemption is also an exemption from the federal gift tax. If an individual makes gifts in one year that exceed the excludable amounts, they can also use the estate and gift tax exemption that applies that year. This will reduce the exemption available for their estate when they die.

For example, the example used earlier involved a never-married person who died in 2019 and left behind an estate worth $20 million. They gave $4 million to charity and were eligible for a basic exemption of $11.4 million. If we assume that this person, during their life, had given away $6 million (not counting the excluded gifts each year), that would mean the $11.4 million basic exemption is reduced by $6 million to $5.4 million. The portion of the estate subject to the estate tax would be $20 million minus $4 million minus $5.4 million, which comes to $10.6 million.

Estate and gift taxes have other rules to prevent individuals from avoiding them. For example, there are rules that are supposed to ensure that any gifts given or bequeathed to individuals by placing them in a trust do not escape taxes. But the rules have several massive loopholes which President Biden and several Congressional Democrats have proposed to close.

One loophole involves placing assets in a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT), which is structured to provide an annuity payment from the assets. The trust is arranged to give the remaining value of the assets – any value that the assets have above and beyond what will be paid back to the grantor in annuity payments – to the beneficiaries of the trust as a gift, which is subject to the federal gift tax.

However, wealthy people often create “zeroed out” GRATs, meaning the gift (the value of the assets beyond the annuity payments) is zero according to the formula specified in the tax law.

Over the duration of the trust, sometimes that turns out to be true – the assets might perform only as well or more poorly than calculated, meaning there really is no gift to the trust beneficiaries – and the grantor takes back the assets placed in the trust. But if the assets perform better than expected, the trust pays the annuity payments to the grantor and then the remaining assets go to the trust as a tax-free gift.

The formula used to determine the value of the assets when the trust was set up (which determined that no taxable gift was provided to the beneficiaries of the trust) is never retroactively corrected. This means that asset value has been passed to the trust beneficiaries (usually family members of the grantor) without triggering the gift or estate tax that would normally be due on such a transfer.

Wealthy people set up multiple GRATs knowing that they will avoid taxes whenever the assets in the trusts perform better than expected and that they will lose nothing when the assets do not.

Another loophole begins with an individual setting up a trust and selling an asset to it. No gift tax applies because the transfer was a sale, not a gift. For purposes of the income tax, the sale has not occurred at all because the grantor owns the trust, which means no tax is due on any capital gains. But for purposes of the gift and estate taxes, the asset is owned by the trust (and eventually, its beneficiaries), which means that any further increase in the value of the asset will be free of gift and estate tax. Further, the grantor can make additional gifts to the trust free of tax by paying the income taxes due on the income generated by the assets in the trust.

The Treasury Department estimates that President Biden’s proposals to close these and other loopholes in the gift and estate taxes would raise $77 billion over 10 years.[8] Sen. Sanders’ estate tax bill also has similar provisions to close these loopholes.[9]

Congressional Republicans Are Not Done Cutting the Estate Tax

Even though the Trump tax law has whittled the estate tax down to its weakest level ever, most Congressional Republicans have, once again, signed onto legislation that would go even further, repealing the estate tax altogether and cutting the gift tax.[10] The last official estimate of this perennial proposal, provided by the Congressional Budget Office in 2015, concluded it would reduce revenue by $269 billion over a decade.[11] The revenue impact today undoubtedly would be much greater.

As the figures in this report have demonstrated, the hundreds of billions of dollars forfeited by the federal government under this proposal would go to a fraction of 1 percent of Americans. This would further enrich those families who already have benefitted more than anyone else from the society and economy that all Americans have worked to build and paid for with their tax dollars.

Endnotes

[1] Congressional Budget Office, “Trends in the Distribution of Family Wealth, 1989 to 2019,” September 27, 2022. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57598

[2] Christopher Ingraham, “People Like the Estate Tax a Whole Lot More When They Learn How Wealth Is Distributed,” February 6, 2019, Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2019/02/06/people-like-estate-tax-whole-lot-more-when-they-learn-how-wealth-is-distributed/

[3] For an analysis of the proposal from Congressional Republicans to make permanent the Trump tax law provisions generally, see Steve Wamhoff, Joe Hughes and Matthew Gardner, “Extending Temporary Provisions of the 2017 Trump Tax Law: National and State-by-State Estimates,” May 4, 2023. https://itep.org/extending-temporary-provisions-of-the-2017-trump-tax-law-national-and-state-by-state-estimates/

[4] Penn Wharton Budget Model: “Senator Bernie Sanders' Estate Tax: Budgetary Effects,” January 23, 2020. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2020/1/23/sanders-estate-tax

[5] For the 99.5% Act: Summary of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Legislation to Tax the Fortunes of the Top 0.5%. https://www.sanders.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/Estate-Tax-Bill-2023.pdf

[6] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.,” October 13, 2022, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/the-geographic-distribution-of-extreme-wealth-in-the-u-s/

[7] Realized capital gains are usually calculated as the profit from selling an asset, meaning the money received for the asset minus the “basis,” which is usually the amount paid to purchase the asset. When assets are passed on to heirs, the basis is “stepped up” to the value of the asset when it is inherited. For example, if some asset is originally purchased at a value of $50 million and is then passed to an heir at a current value of $100 million, the heir can immediately sell the asset for $100 million without reporting any capital gain. This rule allows an enormous amount of capital gains to go untaxed.

[8] Department of the Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2024 Revenue Proposals,” March 9, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2024.pdf

[9] For the 99.5% Act: Summary of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Legislation to Tax the Fortunes of the Top 0.5%. https://www.sanders.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/Estate-Tax-Bill-2023.pdf

[10] Senator John Thune, press release, “Thune Leads Effort to Permanently Repeal the Death Tax,” March 30, 2023. https://www.thune.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2023/3/thune-leads-effort-to-permanently-repeal-the-death-tax

[11] Congressional Budget Office, H.R. cost estimate of 1105, Death Tax Repeal Act of 2015, April 2, 2015. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50100