Local Earned Income Tax Credits: How Localities Are Boosting Economic Security and Advancing Equity with EITCs

reportKey findings

• Leading localities are using refundable earned income tax credits (EITCs) to boost incomes and reduce taxes for workers and families with low and moderate incomes. These local credits build on the success of EITCs at the federal and state levels, reduce economic hardship and improve the fairness of the tax code.

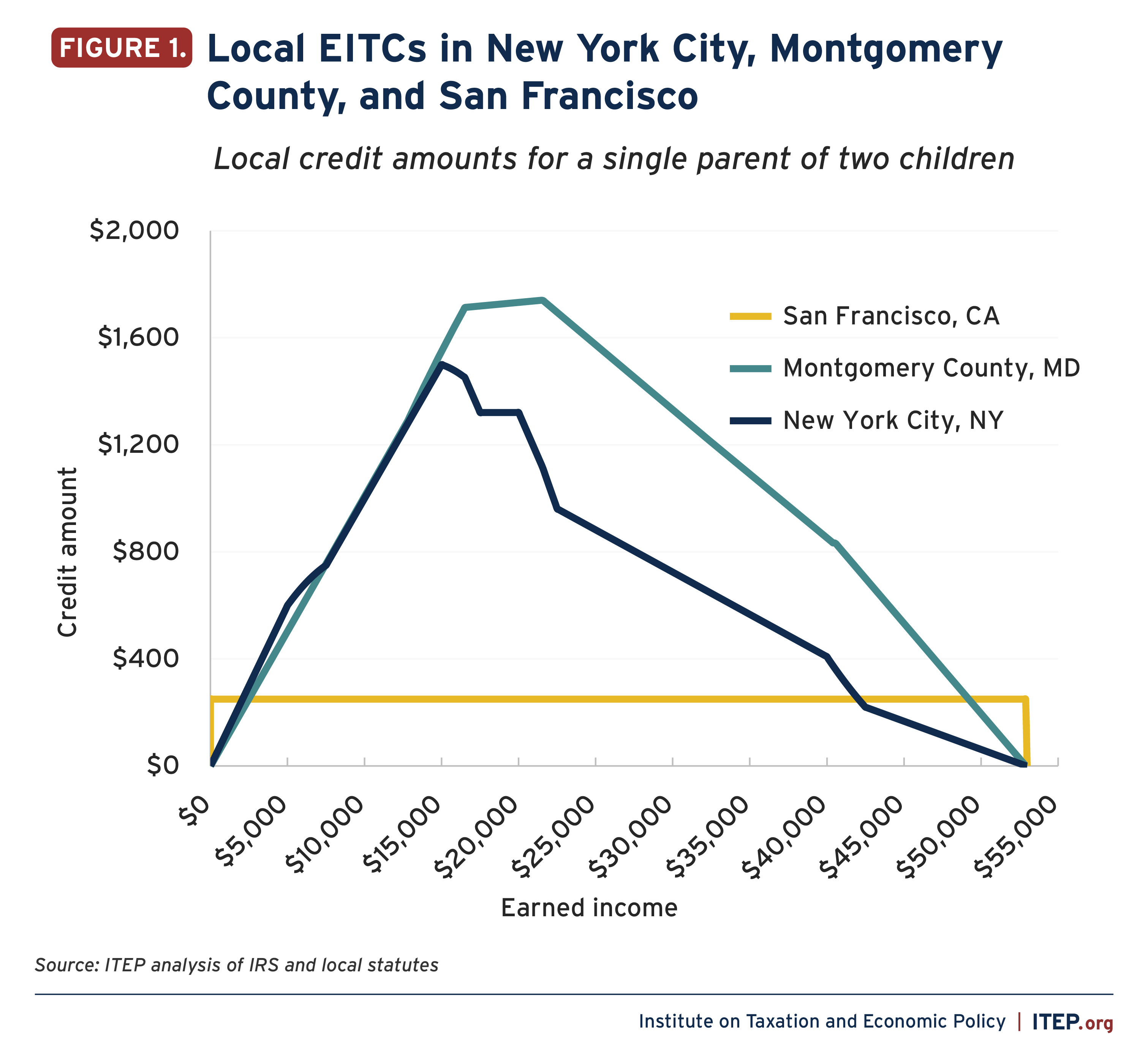

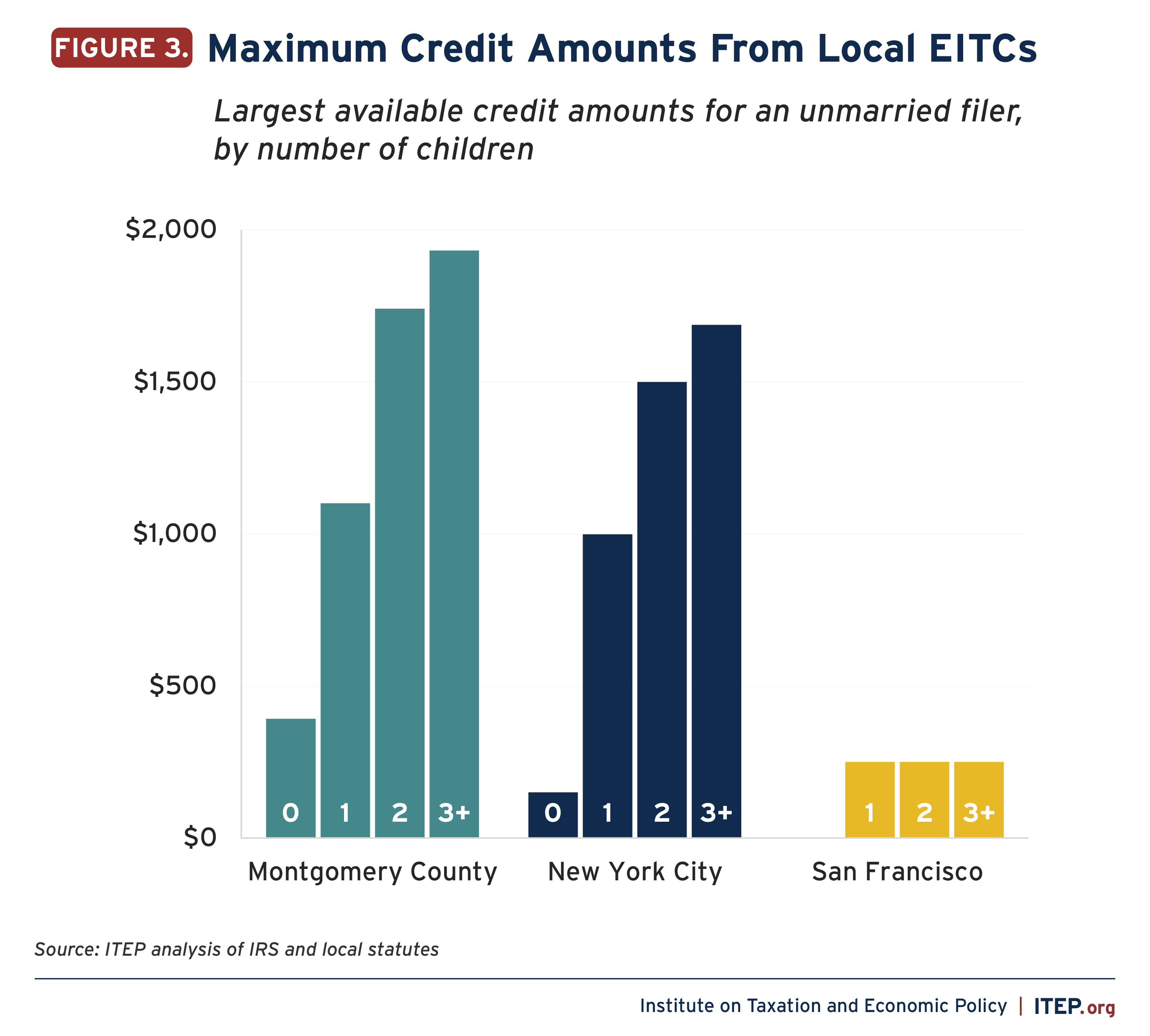

• Today, three places offer local refundable credits linked to the EITC. Maryland’s Montgomery County matches up to 32 percent of the federal EITC for families with children and up to 67 percent for workers without children. New York City matches up to 30 percent of the federal credit. San Francisco offers an annual credit of $250 per family. In addition, two dozen localities in Maryland and Pennsylvania offer nonrefundable EITCs or similar credits.

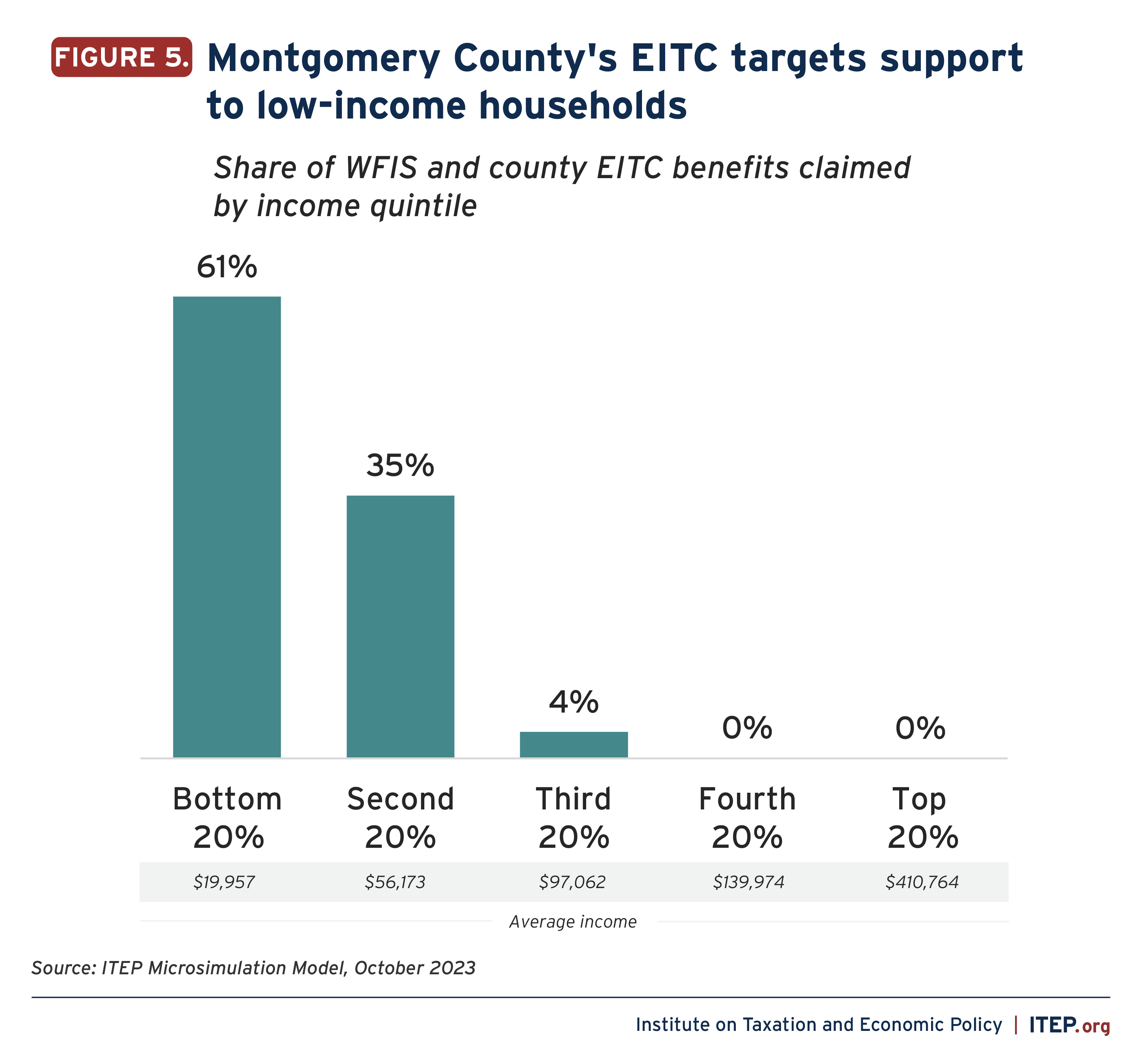

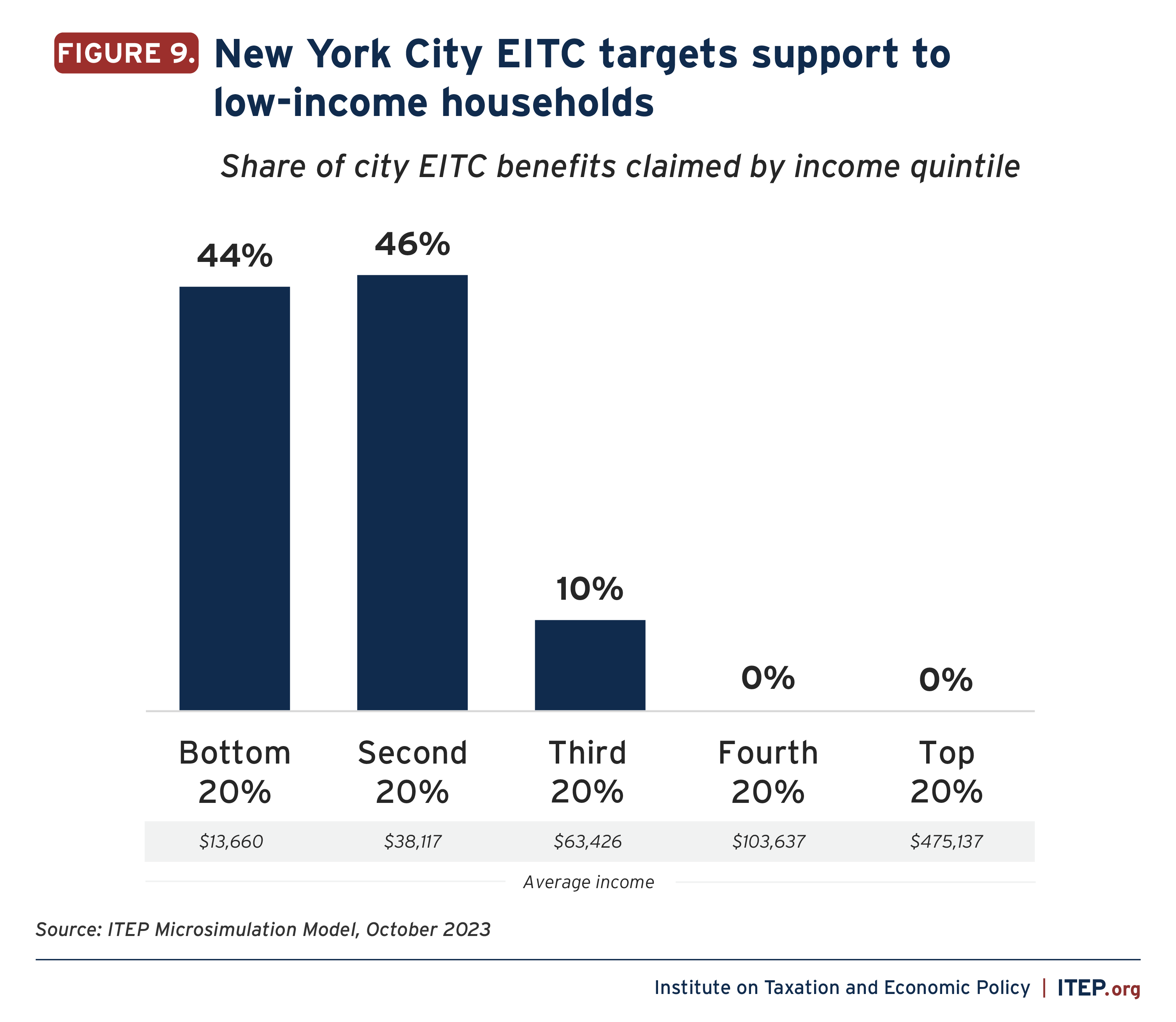

• Refundable local EITCs make a meaningful difference for households with low incomes. Local EITCs in Montgomery County, New York City, and San Francisco together lift the incomes of approximately 700,000 households by more than $350 million each year in addition to federal and state tax credits. We find that households in the bottom two-fifths of local income earners receive over 95 percent of the boost provided by Montgomery County’s EITC, and 90 percent of the boost in New York City.

• Refundable local EITCs improve the economic security of workers, families, and children. These credits put dollars directly into the pockets of financially vulnerable households, helping them afford the basics and achieve better health and economic outcomes. We find this supports racial equity: New York City’s credit reaches larger proportions of Hispanic and Black households relative to their population share, for instance. Studies also find robust local EITCs improve the health of newborns, a key predictor of long-term health, education, and earnings.

• To build an effective EITC, local leaders should consider the size and structure of the credit, who is eligible, and how it is administered. Experience shows a credit will work best if it is refundable, inclusive of the most financially vulnerable households, and administered in a streamlined and accessible manner to facilitate use. Collaboration and partnership across levels of government can help fulfill these principles.

Introduction

Local governments play an essential role in fostering conditions that enable residents to live thriving, healthy lives. Cities, counties, and towns act as the front line in shaping economic opportunity, public health and safety, and the success of future generations. Investments in education, health, infrastructure, and other services have long formed the foundation of this commitment. But communities and local leaders are increasingly recognizing the need to look deeper. To directly address inequities holding residents back, localities are uncovering the transformative potential of investing directly in people themselves.[1]

Tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, offer one promising path forward. The EITC boosts the after-tax income of households by providing an annual tax credit targeted to workers with low and moderate incomes. It’s an approach with a powerful track record of lifting workers and families from poverty, promoting upward mobility, and rebalancing upside-down tax systems.

The federal EITC, in place since 1975, reaches approximately 25 million households in every corner of the country, directly raising incomes and helping to offset some of the taxes these households pay.[2] Thirty-one states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico offer their own credits as well, typically matching a certain percentage of residents’ federal EITC.[3] Crucially, the federal EITC and most state credits are refundable, meaning households can receive the credit regardless of how much they owe in income tax.

At the local level, three leading localities — Maryland’s Montgomery County, New York City, and San Francisco — invest in their people through their own refundable EITCs. These credits deliver an added boost for financially vulnerable community members, together lifting the incomes of approximately 700,000 households by more than $350 million each year.

- Montgomery County’s Working Families Income Supplement matches up to 25 percent of the federal EITC for families with children and 56 percent for workers without children. Residents can also claim a separate nonrefundable EITC to reduce county income taxes. Together these credits mean families with children receive a local EITC worth up to a third of the federal credit and workers without children receive a local EITC worth up to two-thirds of the federal credit.

- New York City’s Earned Income Credit matches between 10 and 30 percent of the federal EITC, with the highest match targeted to very low-income households.

- San Francisco’s Working Families Credit offers $250 per household to families with children who claim the federal or California EITC.

This report examines the power of local refundable credits to support workers, families, and communities. We assess the impact and effectiveness of local EITCs, drawing on the experiences of Montgomery County, New York City, and San Francisco to identify key insights and policy considerations for leaders across the country. We also present new results from ITEP’s Tax Microsimulation Model showing the potent income-boosting impact of local EITCs for workers and families, and how this can advance racial equity.

Lessons from these programs hold relevance for any leader or community member seeking a stronger, fairer, and healthier local community. Local refundable credits like the EITC can help create a strong foundation for families and communities to thrive. Credits that are effectively structured and implemented can deliver a meaningful boost for low-income workers and families and improve outcomes in health, education and help localities fund public services more fairly.

Why a Local EITC?

As localities look to provide a stronger foundation for families and communities to thrive, well-designed local refundable credits like the EITC are an effective option. Substantial evidence on these credits at the federal, state, and local level illustrates why: having inadequate resources holds people and communities back. By directly bolstering households’ resources, refundable credits help workers and families get by and achieve their potential. The results are stronger outcomes and greater equity in health, education, employment, and more.[4] The EITC is an investment in families with significant positive returns.

Spotlight: Local EITCs and Health

Robust local EITCs in Montgomery County and New York City are helping children and families live healthier lives, studies find.

In Montgomery County, the creation of the Working Families Income Supplement reduced the occurrence of children being born with low birth weight by one-fifth for low-income mothers who received the supplement during pregnancy, according to a peer-reviewed 2019 study.[5]

In New York City, introduction of the Earned Income Credit reduced low-weight births by about 2 percent across the city’s low-income neighborhoods, the results of a peer-reviewed 2017 study indicate.[6] The results are for all births in these neighborhoods, including parents who are EIC participants and those who are not.

A child’s weight at birth is a key predictor of long-term health, education, and earnings. By lifting family incomes, local credits like the EITC can improve outcomes at birth — and, in turn, promote well-being and upward mobility over the long run — by supporting families’ economic security, reducing stress, and supporting maternal health.[7] These results parallel findings on the positive health impacts of EITCs at the federal and state levels.[8] Evidence also links the family economic support provided by the EITC to reductions in reports of youth violence and juvenile justice system involvement.[9]

The EITC supports families of all races and ethnicities. The benefits are especially significant for households of color, making progress against systemic disparities in economic security and opportunity. The credit reaches a larger proportion of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous households relative to their share of the overall population and provides these households a greater share of the total income boost.[10],[11] This is largely because workers of color, in particular Black and Hispanic workers, are disproportionately represented in lower-paid jobs as a result of historical and ongoing barriers including discrimination and underinvestment.[12] Targeted refundable credits address these inequities, advancing shared opportunity and promoting more economically inclusive communities for current and future generations.[13]

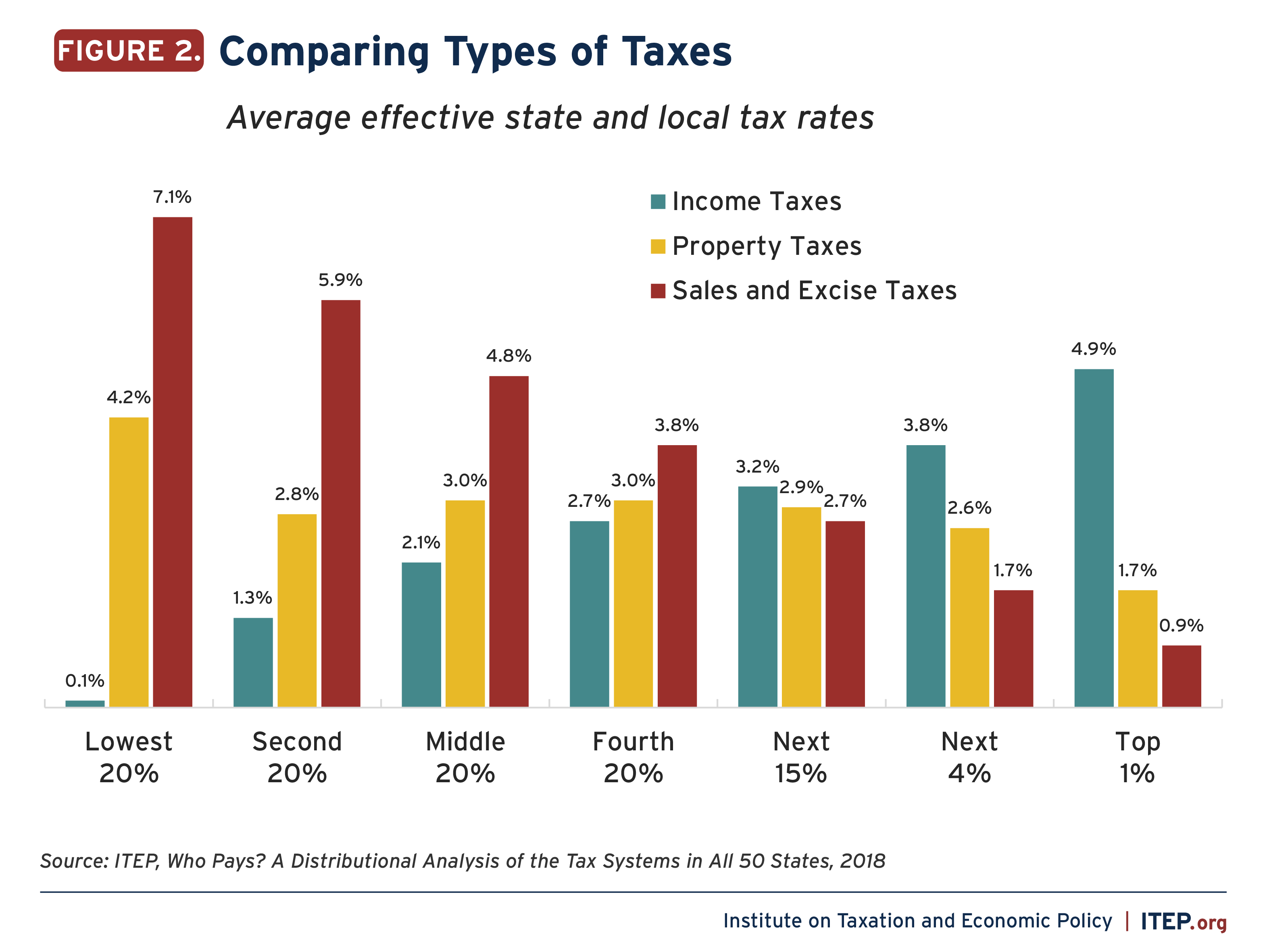

Refundable credits also help local governments address a longstanding inequity: upside-down tax codes. Local tax policies too often leave poorer residents paying a disproportionately large share of taxes, worsening economic divides within and across communities.[14],[15] Credits for households with low and moderate incomes can rebalance revenue systems by putting more dollars into the pockets of residents with limited financial means. Importantly, a local EITC can be effective whether or not a locality levies an income tax, as long as the credit is refundable. If a credit is refundable it will reach beyond a household’s income tax liability, offsetting amounts paid in local sales, property, and other taxes. These credits improve the fairness of the tax systems localities use to fund shared priorities.

Administrative considerations make the EITC an especially powerful way for localities to directly reach residents in need. Local tax credits build on the established administrative infrastructure of state and federal tax credits, offering a relatively straightforward and efficient way to achieve high participation in communities. Each year 25 million low- and moderate-income households claim the federal EITC. The federal credit reaches families across all corners of the U.S. and lifts millions of people from poverty.[16],[17] State EITCs provide an added boost in 31 states plus D.C. and Puerto Rico, and a growing number of these states have broadened participation for their EITCs to groups excluded from the federal credit.[18] A robust network of national and community institutions spread awareness of the credit and help families claim it. These factors provide a strong base for localities to build upon with their own refundable credits.

Local EITCs in Action: An Overview

Working families get a boost from refundable local EITCs in three places: Maryland’s Montgomery County, New York City, and San Francisco. Together these local EITCs reach around 700,000 households and raise incomes by about $350 million each year. The three programs all aim to improve economic security for workers, families, and communities. Each local credit has a unique structure, reach, claiming and administrative process, and history.

Montgomery County’s Working Families Income Supplement and a nonrefundable county EITC together provide a local match up to 32 percent of families’ federal EITC. The county provides a larger credit for workers without children in the home, up to 67 percent of the federal credit. The refundable portion of the credit, the Working Families Income Supplement, was established in 1998 and most recently expanded in 2020.[1] Montgomery County and Maryland partner to automatically deliver the refundable credit to county residents claiming the Maryland EITC each year. Montgomery County’s EITC reaches around 70,000 households, raising incomes by an average of approximately $600 per household. The program provides a meaningful targeted boost: around three-fourths of local EITC participants are in the poorest 20 percent of county residents, with household incomes below $38,000, according to results from ITEP’s Tax Microsimulation Model.

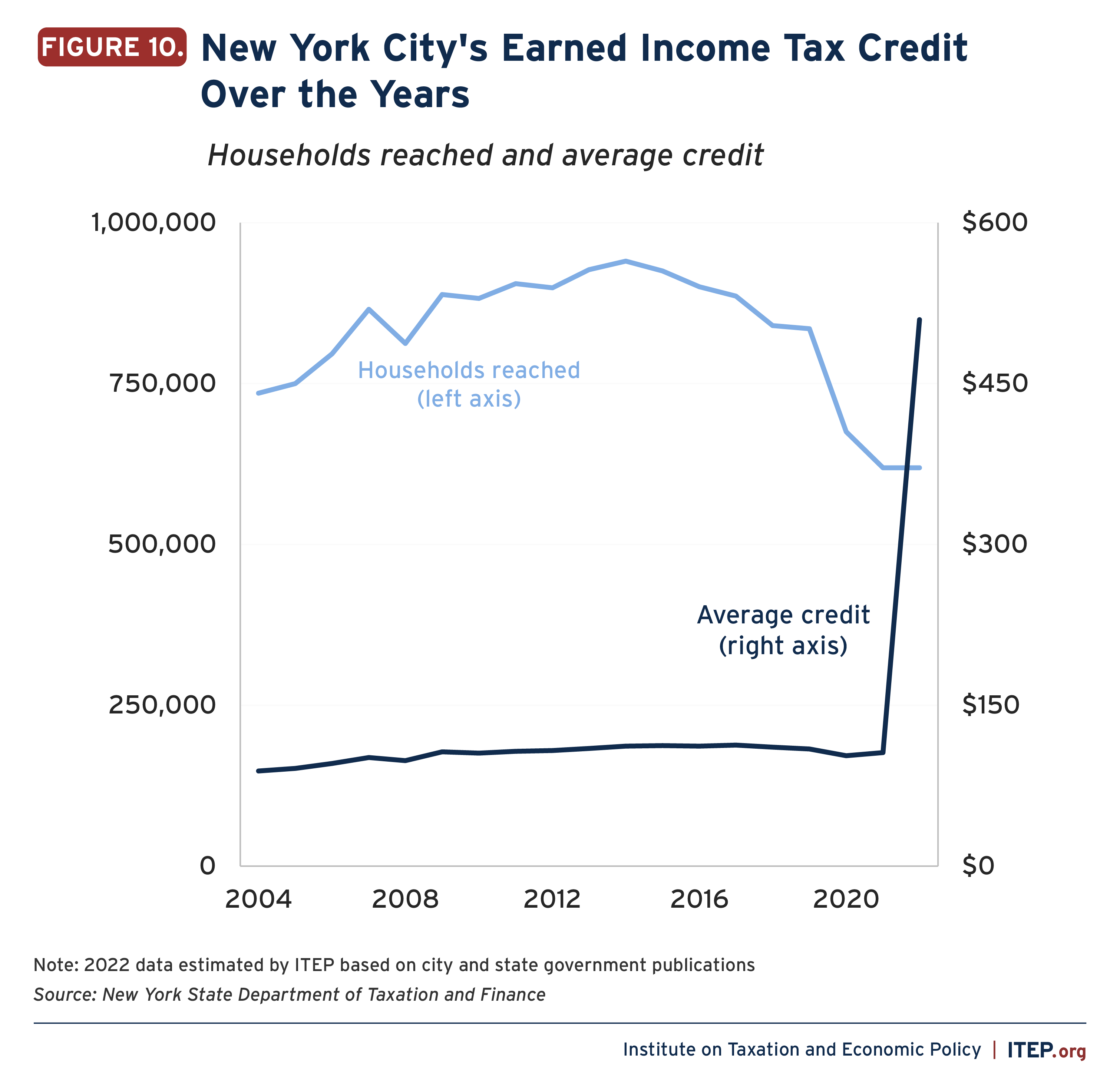

New York City’s Earned Income Credit matches between 10 and 30 percent of residents’ federal EITC. The match rate is highest for households with very low incomes and it phases down incrementally as income rises. Residents claim the Earned Income Credit at tax time while completing their annual New York City income tax returns. Established in 2004 and expanded in 2022, the credit today reaches around 620,000 households and boosts incomes by an average of about $510. The credit delivers a targeted lift: around half of households claiming the credit are in the poorest 20 percent of New York City residents, with household incomes below $25,000, according to results from ITEP’s Tax Microsimulation Model. The credit also supports racial equity, providing a boost to Hispanic and Black households in larger proportion to their shares of the overall population of New York City tax filers, our estimates show.

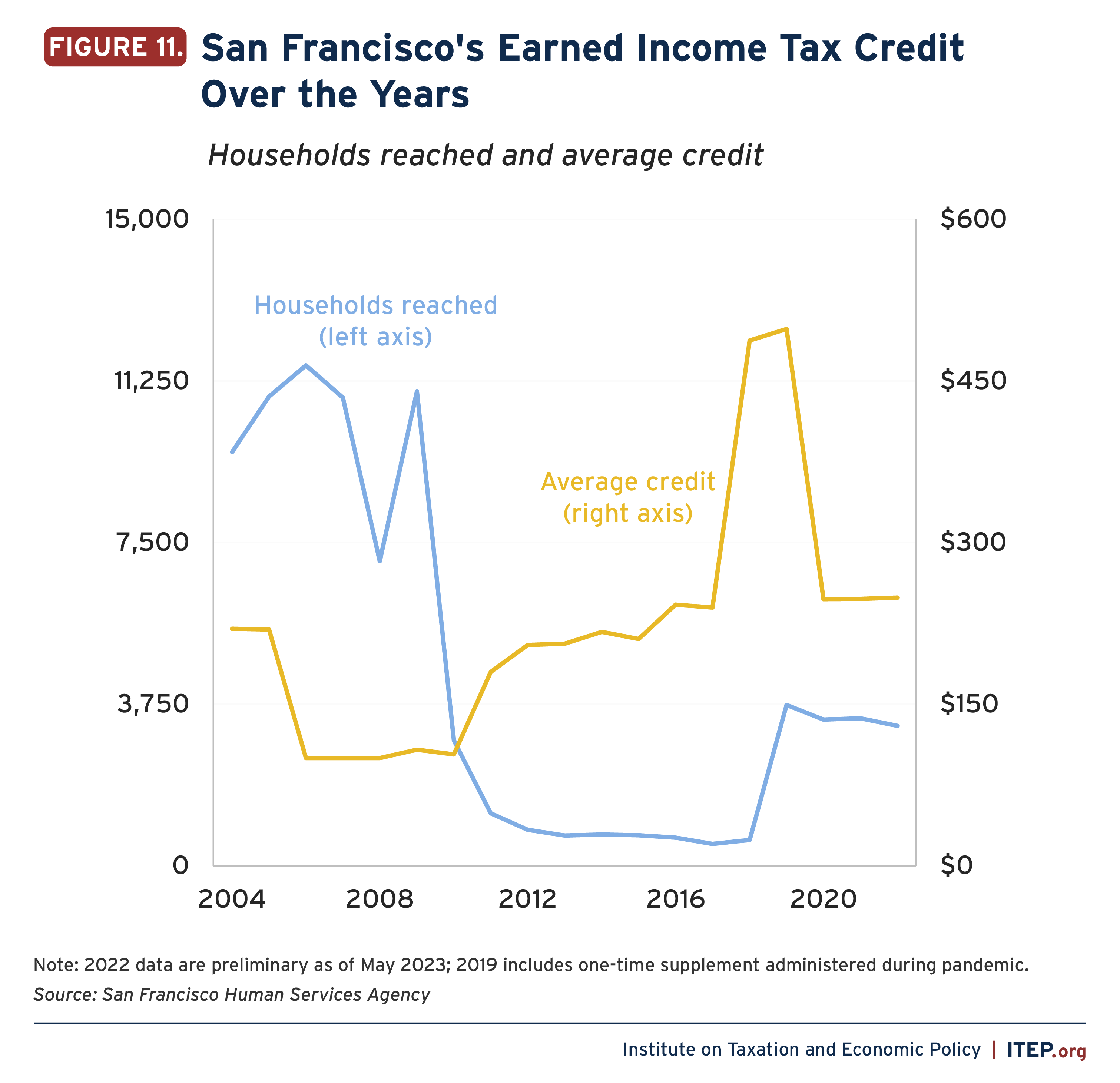

San Francisco’s Working Families Credit offers a rebate of $250 per household to families with children who claim the federal or California EITC. Families claim the credit by applying to the city with a copy of a federal or state tax return to confirm eligibility. San Francisco’s credit was established in 2004. The program currently reaches approximately 3,500 families each year. San Francisco delivered an additional rapid cash payment to participating families in 2021, building on the WFC to further bolster household resiliency during the pandemic economic downturn.

The landscape of local EITCs also includes pilot programs and nonrefundable credits. Local EITCs have been piloted in cities including Denver and Chicago. These programs generated improvements for residents’ economic well-being and uncovered critical insights that have influenced policy at federal, state, and local levels.[19],[20] In addition, Philadelphia and 23 localities in Maryland offer nonrefundable EITCs or similar credits for low-income workers.[21],[22] These nonrefundable credits reduce households’ city or county income taxes, making local income taxes more equitable. But they provide no refund for any amount of the credit that exceeds income tax liability, leading to smaller benefits for households with lower incomes.

The local EITCs in place today show the potential and power of refundable credits to strengthen communities. These credits can be an effective way to uplift workers and families, delivering a direct and targeted income boost that improves health, education, and earnings — all while advancing fairness in local revenue systems. Lessons from local EITCs in place today can help communities overcome challenges and create successful programs.

Building Effective Local Refundable Credits

Targeted local refundable tax credits like the EITC can help families and communities thrive by strengthening economic security, improving health and education outcomes, and rebalancing regressive tax systems. Local credits work best when they are refundable, inclusive of the most financially vulnerable households, and administered in an accessible manner that facilitates participation. To build an effective EITC or other targeted refundable credit, local leaders should consider the size and structure of the credit, who is eligible, and how it is administered.

Structure

Refundability is a vital component of any local credit for households with lower incomes. A refundable structure ensures that the boost a person receives is not constricted by the amount she owes in local income taxes. This can be especially important at the local level as localities generally rely more on property, sales, and excise taxes to raise revenue, and four in five local areas nationwide do not have local income taxes at all.[23] Refundable structures deliver more dollars to where they can have a greater impact on reducing poverty, improving well-being, and rebalancing inequitable tax codes.

Local EITCs in place today illustrate the importance of refundability. In San Francisco, residents do not pay a local personal income tax. Rather than offsetting income taxes, San Francisco’s refundable EITC-linked Working Families Credit operates as a cash transfer program that directly lifts families’ incomes. In Montgomery County, residents pay a 3.2 percent local income tax. The county’s EITC reduces the impact of this tax on households with low-to-moderate incomes. But the largest share of Montgomery County’s EITC, roughly two in three local EITC dollars, takes the form of direct refunds to households that can go above and beyond local income tax liability. These refunded amounts prove especially meaningful for workers and families with lower incomes, helping the lowest-earning 20 percent of county residents secure over 60 percent of the local EITC, according to our estimates.

Localities are also innovating by crafting credits that build on the federal EITC to provide an even better-targeted boost. One powerful example is Montgomery County’s enhanced EITC match for workers without children in the home. The county provides these workers a match of up to 67 percent of the federal EITC, approximately double the match rate available to families with children. This structure helps offset the comparatively small federal EITC available to noncustodial parents and workers who do not have children, adding a local boost of nearly $400 on top of the maximum $600 federal credit for these workers.

Other notable approaches providing a greater lift to households with low earnings include New York City’s increased credit rate for lower-income households and San Francisco’s guaranteed credit amount. In New York City, a larger match on the federal EITC is available to residents with lower incomes: households with incomes below $5,000 can claim a 30 percent match, and the match rate declines in increments to 10 percent as income rises. San Francisco’s full $250 credit is available to families with as little as one dollar in earnings. This guaranteed minimum credit allows some workers with very low earnings to receive more from the local credit than they do from the federal EITC. These examples show localities can build on the success of federal and state EITCs while making adjustments that advance local priorities and community needs.

Eligibility

Localities are making strides on inclusive EITCs. To make their credits more powerful tools for advancing economic opportunity, localities are broadening eligibility to make up for gaps in the federal EITC that leave out immigrant families, older workers, and younger workers.

In Montgomery County and San Francisco, for example, local EITCs are available to U.S. citizens as well as immigrant people who live and work in the U.S. and pay taxes with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers. These noncitizen workers who have not been issued Social Security numbers are excluded from the federal EITC and Child Tax Credit even if they have children or spouses who are U.S. citizens; work and pay federal, state, and local taxes; and otherwise meet the income requirements for the credit.[24],[25] Montgomery County and San Francisco follow Maryland, California, and a growing number of other states in making their EITCs available to workers and families regardless of immigration status. Ten states and D.C. have expanded their EITCs to immigrant families.[26]

Montgomery County also makes its credit more age-inclusive. Under federal EITC rules, a low-income worker without children in the home is not able to receive the credit if older than 64 or younger than 25.[27],[28] Montgomery County follows Maryland in filling these critical gaps, expanding eligibility for the county EITC to younger adults and older workers who otherwise fulfill the income requirements for the credit.[29] Today eight states including Maryland and California allow younger workers to claim their EITCs, and three states include older workers.

Accessibility

One strength of a local EITC is that it allows localities to build on the existing take-up and administrative infrastructure of EITCs at the state and federal levels. With mindful steps, local governments can make the most of this strength to reach eligible residents effectively and efficiently.

In considering strategies to facilitate participation in a local credit, it is helpful to distinguish between two categories of eligible people: those already claiming federal and/or state EITCs, and those who are eligible but not yet claiming them.[30] In all, the EITC reaches approximately 8 in 10 eligible households federally, the IRS estimates.[31] Coordination between levels of government can help localities efficiently deliver a local credit to households already using federal and state EITCs. Local governments can also strengthen and support efforts to increase participation among eligible households not yet claiming these credits. Focusing on coordination, partnership, and minimizing administrative barriers can reach residents in both groups, making a local credit accessible and impactful for all eligible households.

Montgomery County shows one practical and powerful approach. The county partners with the state of Maryland to automatically deliver the refundable portion of its county credit, the Working Families Income Supplement, to all residents receiving a refund from the Maryland EITC. These residents get the WFIS deposited into their bank accounts or delivered by mail with no additional application or process required. As a result of this partnership, Montgomery County delivers an automatic, targeted, and meaningful income lift to tens of thousands of low-income workers and families each year, achieving the same level of participation as the state EITC.

Montgomery County’s user-friendly approach also saves on administrative costs, allowing more resources to be directed into families’ pockets or into outreach to communities facing elevated barriers to access. The county reimburses the state for its WFIS operating expenses, which total less than one-fifth of 1 percent of the amount spent on the credit itself, or less than $1 per household reached.[32] Importantly, while Montgomery County has a local income tax, the state-local partnership used to administer the WFIS can function as a model for implementing refundable local EITCs even in places without local income taxes. This is particularly true where state EITCs or state income taxes are in place.[33] Such partnerships can be especially useful in allowing localities to overcome constraints from federal policies that limit some local governments’ ability to verify the EITC eligibility of residents.[34]

In cases where a local claiming process is used, localities can keep the process simple and straightforward. Key principles include meeting residents where they are and minimizing barriers to access. New York City, for example, integrates its Earned Income Credit into the annual tax filing process, making it accessible for residents who pay city income tax and have claimed the federal and New York state EITCs. The city also partners with the IRS to identify residents who appear eligible for the credit but have not claimed it, contact these residents, and send them pre-filled amended tax return forms that can be submitted to claim the local, state, and federal EITCs.[35] The NYC EIC Mailing Project has helped tens of thousands of New York City households secure credits that would have otherwise gone unused.[36]

Local tax credits can also boost residents’ access to federal and state credits and other supports that build economic security. New York City, Montgomery County, and San Francisco each leverage their local EITCs to promote free tax filing and broader financial empowerment efforts.[37],[38],[39] San Francisco also connects Working Families Credit participants to services such as Medicaid and nutrition assistance and facilitates access to the credit among residents already enrolled in these support programs.[40] In addition, some evidence at the state level suggests robust EITC supplements lead to increased participation in the federal credit, bringing more dollars into households’ pockets and local economies.[41] These examples demonstrate how local credits can be a tool to strengthen partnerships between public institutions, tax assistance providers, outreach coalitions, and community-based organizations to better support residents in need.

Sustainability

Refundable credits like the EITC are an effective tool for advancing economic security and rebalancing inequitable tax codes. Equitable revenue-raising strategies can help ensure a local credit is sustained over time, allowing families and communities to feel the long-term benefits on health, education, and employment. A local refundable credit can be especially powerful as one part of an approach that leverages public investments and revenue policies to achieve stronger communities in which all residents can thrive, and in which those with the greatest ability to pay contribute fairly.

Local EITCs in Action

Working Families Income Supplement | Montgomery County, Maryland

Overview and Impact

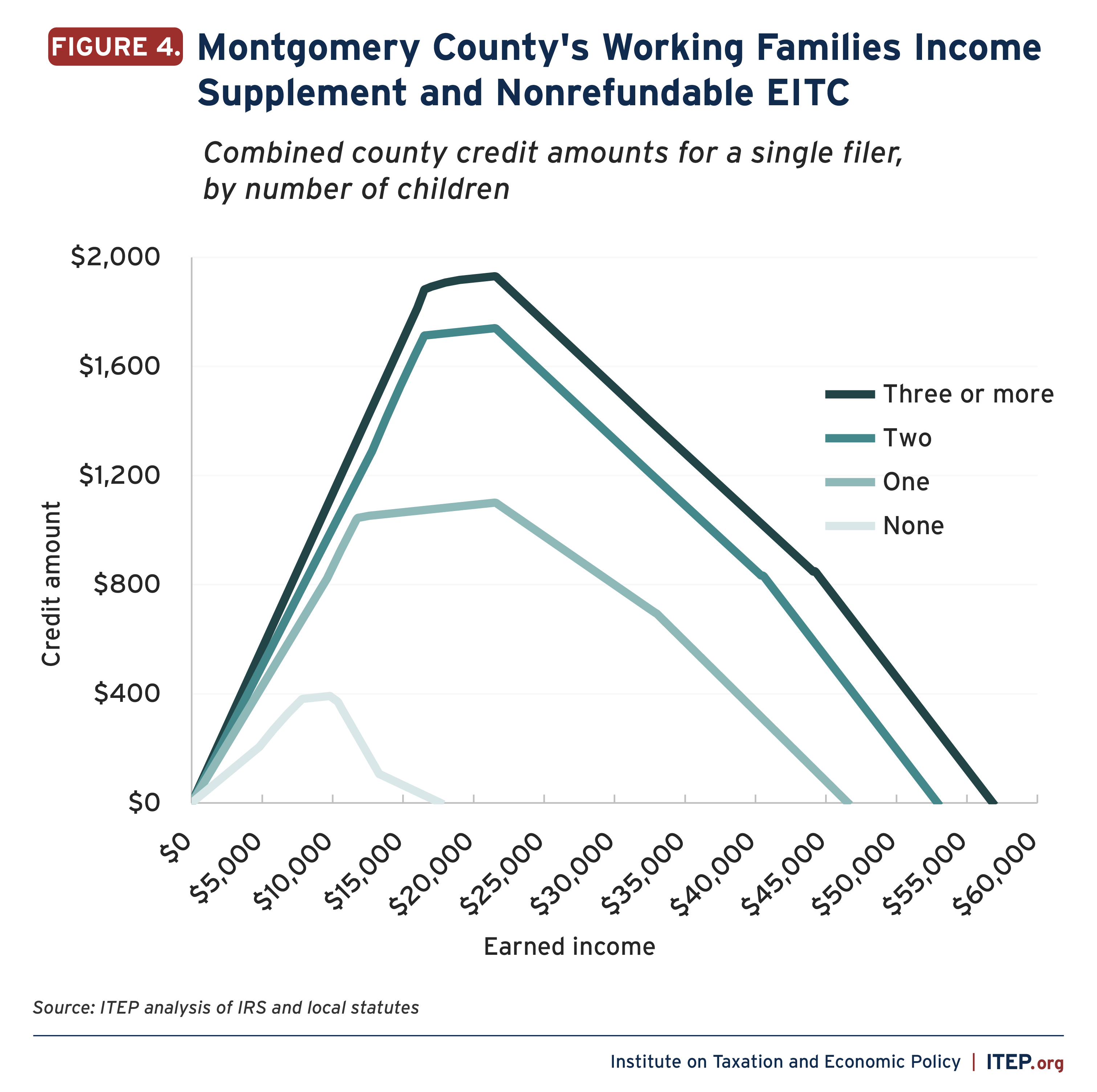

Residents of Montgomery County, Maryland, are eligible for two local tax credits based on the federal EITC. In this report, the two credits are referred to together as the Montgomery County EITC. The most substantial portion is the refundable Working Families Income Supplement (WFIS), which matches part of the refund residents receive from the Maryland EITC. A nonrefundable county EITC is available separately to offset county income taxes for lower-income residents. The WFIS was introduced in 1998, making it the first local refundable EITC in the nation.[2] Today many households claim both credits, and in combination they provide an amount similar to what a single refundable local EITC would provide.

Around 70,000 households claim Montgomery County’s EITC each year, receiving an income supplement from the WFIS, an income tax reduction from the nonrefundable credit, or both.[42] These households see their incomes lifted by approximately $40 million, or around $600 per household on average. The refundable WFIS delivers the bulk, while the nonrefundable credit contributes about a third.

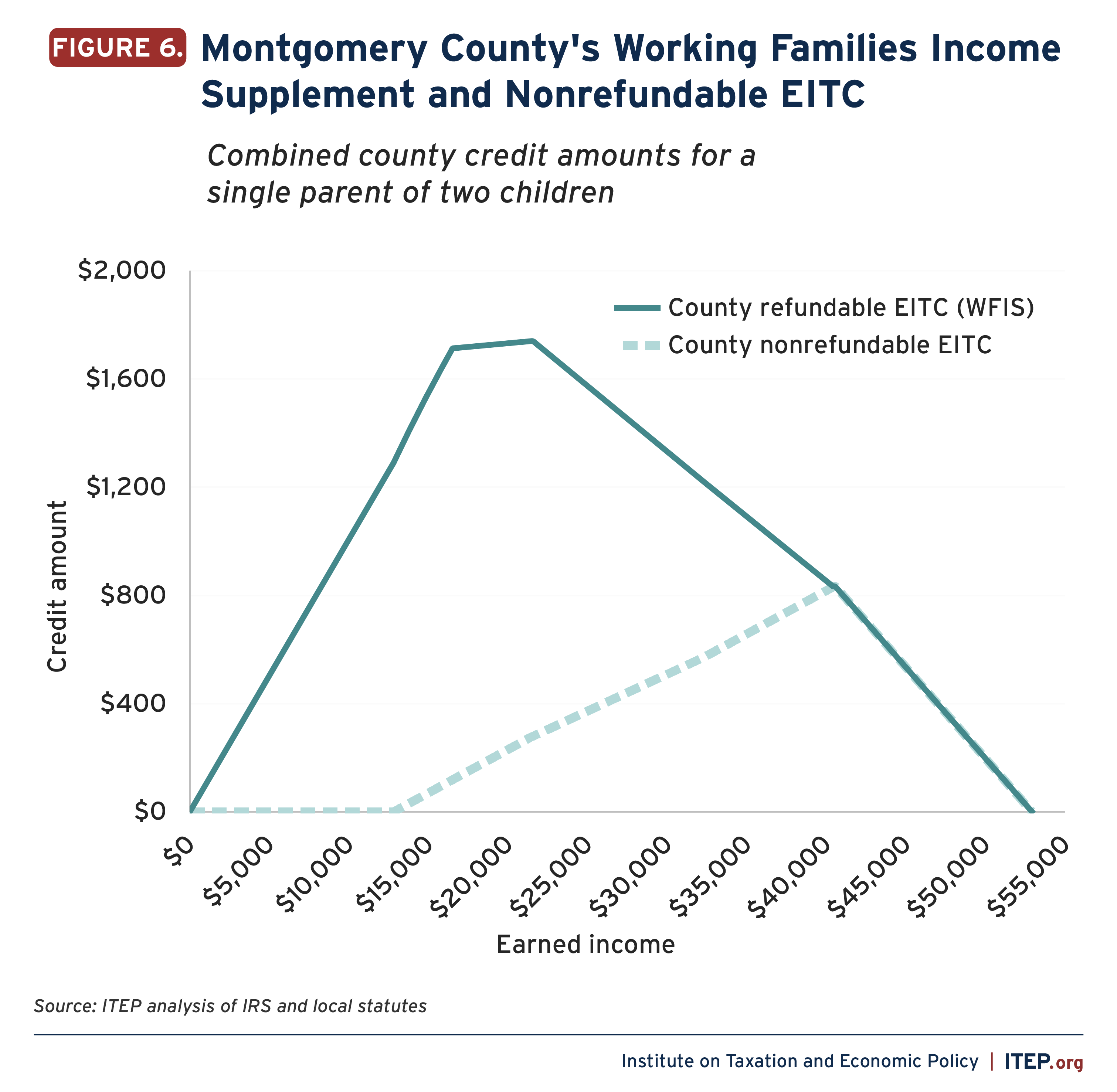

Montgomery County matches between 25 and 32 percent of the federal EITC for families with children and up to 67 percent of the federal credit for workers without children, making it overall the most robust refundable local EITC in the nation. A single worker can receive a boost of up to nearly $400 if she has no children at home, $1,100 if she has one child, $1,740 if she has two children, and nearly $2,000 if she has three or more children. These credit levels provide a strong foundation for workers and families of all sizes while helping to offset some of the additional cost families incur with each additional child.

The gains are targeted to low-income workers and their families, our estimates show. Households claiming the county EITC have an average income of $26,000, far less than the $145,000 average household income of the county.[3] Three in four households claiming the EITC have incomes that put them in the lowest 20 percent of Montgomery County income earners. These households, who have incomes under $38,000, receive 61 percent of the income boost provided by the county’s EITC. Over 95 percent of local EITC dollars flow to households in the bottom two-fifths of Montgomery County income earners.

Households claiming the Montgomery County credits see their income lifted by an average of just over 2 percent, equivalent to more than an extra week’s paycheck worth of income annually. The effect is greatest for those with lower earnings: households in the bottom 20 percent who claim the credits receive a larger boost relative to their incomes, an average increase of just over 3 percent, according to ITEP estimates.

Montgomery County’s EITC is provided on top of Maryland’s refundable state EITC. Maryland matches between 45 percent and 50 percent of the federal credit for families and 100 percent of the federal credit for workers without children. A family in Montgomery County who claims the state and county EITCs can receive a combined match of up to 82 percent of the federal credit, one of the most robust EITC matches in the country.[43] For a single parent with two children, this means a boost worth up to $4,700 on top of the federal EITC. For a worker with no children in the home, the Maryland and Montgomery County boost can be even larger than the federal EITC: a single worker with no children can receive state and local credits worth up to 167 percent of the federal EITC, equating to nearly $1,000 in added income on top of the federal credit.

The Montgomery County EITC provides a boost to U.S. citizens and to immigrant families who work and pay taxes with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers.[44] It is also available to younger workers and older workers.

The robust size, relatively high uptake, and effective administration of the WFIS have made the program a promising example of a local refundable EITC. Picking up on these strengths, advocates have proposed policies like the WFIS in other local jurisdictions, and the Montgomery County credit has served as inspiration to policymakers across the country from neighboring Prince George’s County to Denver.[45],[46]

Claiming the Montgomery County EITC

The Working Families Income Supplement and nonrefundable county EITC are claimed separately by residents, providing a combined boost similar to what a traditional refundable EITC would provide. The nonrefundable portion is claimed as residents file county income taxes each year. The WFIS is delivered automatically to Montgomery County residents who received a refund from the Maryland EITC, matching a set percentage of the state credit.

Many households who claim the refundable WFIS also claim the nonrefundable credit, and vice versa. For example, a single parent of two children who earns $25,000 is eligible to claim both credits, receiving approximately $1,200 from the WFIS and approximately $375 from the nonrefundable EITC. The nonrefundable credit phases in as household income rises, and the refundable portion phases out. The result is a combined local EITC that is worth up to one third of the federal EITC for families. For workers without children, the combined local EITC credit equals up to two thirds of the federal credit.

The nonrefundable credit reduces county income taxes by an amount equaling up to 32 percent of the federal EITC. Montgomery County’s income tax is a flat rate of 3.2 percent on state taxable income after deductions, exclusions, and adjustments.[47] The nonrefundable county credit reduces the impact of the tax for residents with low-to-moderate incomes. But it does not provide a refund for any amount of the credit that exceeds local income tax liability, limiting its power to boost the incomes of residents with the lowest earnings. All Maryland counties and Baltimore city have a local income tax, as required by state law, and all provide a local nonrefundable EITC.[4] But only Montgomery County offers an additional refundable EITC.[48]

The refundable WFIS is sent directly to Montgomery County residents who claim the refundable Maryland EITC. The WFIS matches 56 percent of households’ state EITC refund. The state refundable EITC, in turn, equals 45 percent of the federal credit for families with children and 100 percent for workers without children, minus any state income tax liability. For families, this means a county refund worth up to one quarter of the federal EITC. For workers without children, the county refund can equal up to 56 percent of the federal EITC.

Families receive the WFIS through a straightforward and simple process, allowing Montgomery County to deliver a boost effectively and efficiently to residents with no added administrative hassle. The Maryland Office of the Comptroller manages the credit on behalf of the county, periodically identifying eligible households who claim the state EITC and automatically sending them the amount they are eligible for from the WFIS. Beyond claiming the state EITC, no additional application is required to receive the WFIS. The comptroller’s office issues checks to eligible households beginning July 31 each year following the close of the tax season in April. The county reimburses the state for costs associated with administering the WFIS. These administrative expenses typically total less than one fifth of 1 percent of overall expenditures on the program.

The county integrates the WFIS into outreach efforts aimed at raising awareness and participation in the state and federal EITCs, using the county credit as an added incentive for residents to file income taxes each year. A 2022 press release encouraging residents to “get all your tax credits,” for example, notes “Montgomery County is among a few jurisdictions across the country — and the only in Maryland — with a local match to the state’s earned income credit,” adding that households may be eligible for thousands of dollars in combined refunds from the federal, state, and county programs.[49] The release also provides information to learn more about free tax preparation assistance services.

Background and History

Working Families Income Supplement

Montgomery County lawmakers enacted the nation’s first local refundable EITC in 1999, naming it the Working Families Income Supplement. For its first year the credit was made available retroactively for 1998, providing a county boost of up to one tenth of families’ federal EITC. The credit was structured as a match to the refundable Maryland EITC and administered by Maryland state government, a structure and approach that continues today, allowing the county to achieve a high rate of participation from the start.

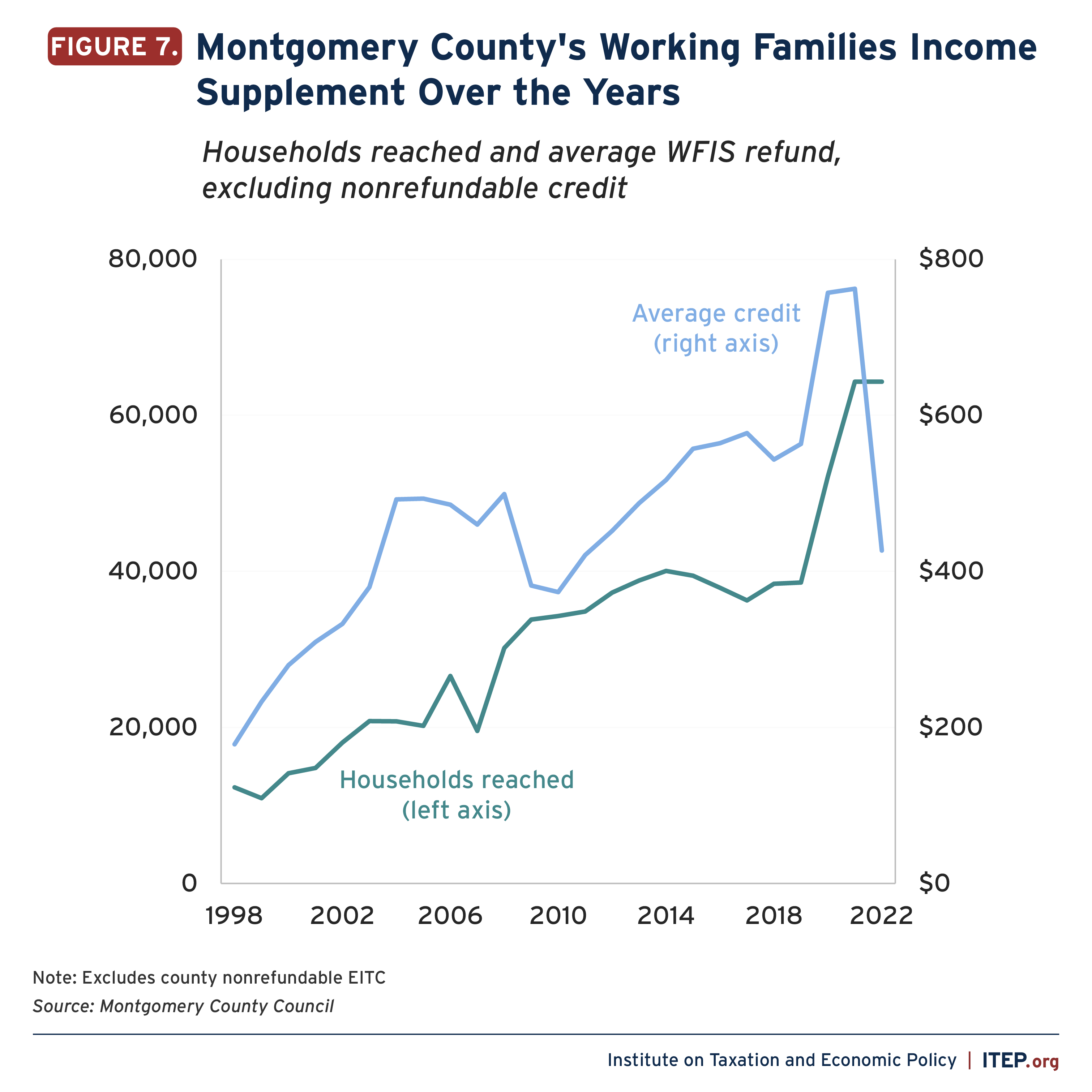

The WFIS has been expanded several times over its quarter-century lifespan. During its first decade in operation, the credit’s value as a percentage of the federal EITC increased from 10 percent to 25 percent, increasing the average credit from approximately $180 to $500 per household.[50],[51],[52] Eligibility for the WFIS also widened to include workers without children in 2008. These expansions were the result of Montgomery County following increases to the state credit that the WFIS is structured upon.54 County lawmakers reduced the size of the credit in 2009 and 2010 during the Great Recession but restored its value in following years.[54],[55],[56],[57]

“This credit will … target the greatest benefits to those with the greatest need, and offset or eliminate completely the local tax burden on working families struggling to make ends meet.”

– Montgomery County Executive Douglas Duncan explaining the Working Families Income Supplement in 1999

Maryland lawmakers substantially boosted the state EITC in 2020, raising the refundable portion to 45 percent of the federal credit.[58] Montgomery County matched the expansion, boosting the WFIS by an equal amount — for a combined state and local credit of up to 90 percent of families’ federal EITC — offering historic help to financially vulnerable residents during a period of unprecedented economic disruption.[59],[60] Montgomery County also followed the state in a series of moves expanding the reach and impact of the EITC for populations excluded or disadvantaged by the federal credit. Workers without children at home, eligible for only a small federal EITC, became eligible for a larger state and county match. Younger workers, older workers, and immigrant families, three groups of people left out of the federal credit, also became eligible for the Maryland and Montgomery County EITCs in 2020.[61],[62]

The 2020 expansions substantially increased the reach and impact of Montgomery County’s EITC. The number of households receiving the WFIS grew two-thirds from 2019 to 2022, and the total amount of support these residents received more than doubled.[63] Montgomery County allocated $50 million in federal recovery funds over two years to facilitate the increases.[64] For 2022 county lawmakers scaled back the credit value expansion while maintaining the broadened eligibility rules for immigrant families, younger workers, and older workers.[65] The result is the current structure: the WFIS matches 56 percent of residents’ state EITC refund, providing a refundable county boost worth up to one-quarter of the federal EITC for families and up to two-thirds of the federal EITC for workers without children and noncustodial parents.

County nonrefundable EITC

Montgomery County’s nonrefundable EITC stretches further back in history. Nonrefundable EITCs were indirectly introduced to Maryland’s counties and cities in 1987, the same year Maryland enacted a nonrefundable state EITC.[66] A 1999 overhaul of Maryland’s income tax structure formally enacted the local nonrefundable EITC, requiring every Maryland county and the city of Baltimore to provide a nonrefundable credit against local income tax.[67] These credits are claimed during the income tax filing process and administered by the state.

The same system remains in place today, allowing all eligible Maryland residents paying local income taxes to claim a local nonrefundable EITC. Nonrefundable local EITCs offset $64 million in local income tax liability for nearly 240,000 Maryland households in 2018, including 33,000 Montgomery County residents receiving $9.5 million in tax reductions.[68] These credits help reduce income taxes for households with low-to-moderate incomes, but provide no additional income boost for any amount exceeding local income taxes owed. Maryland law also permits localities to offer refundable EITCs, but unlike the nonrefundable credit, it is not required.[69]

Earned Income Credit | New York City

Overview and Impact

Low-income workers in New York City can claim the city’s refundable earned income tax credit to reduce their city income tax liabilities and boost their incomes. Introduced in 2004 and expanded substantially in 2022, the NYC Earned Income Credit (EIC) today matches between 10 and 30 percent of the amount a household receives from the federal EITC.[70] Workers with income under $5,000 receive the full 30 percent, and the match rate phases down as income rises. This unique sliding-scale approach builds on the structure of the federal EITC while targeting greater support to households with lower incomes.

The New York City credit reached 620,000 households in 2021.[71] The credit raises incomes of workers and families by an estimated $315 million annually, providing an average boost of about $510 per household.[72] A single worker earning low wages can receive up to nearly $1,700 from the credit if she has three or more children, $1,500 if she has two children, $1,000 if she has one child, and $150 if she does not have children in the home.

The boost from New York City’s EIC is targeted to low-income workers and their families, according to our estimates. Households claiming the city credit have an average income of just $29,000, far less than the $139,000 average household income of New York City at large. Half of households claiming the EIC have incomes that put them in the lowest 20 percent of New York City income earners. These households, who have incomes under $25,000, receive 44 percent of the income boost provided by the EIC. Nine in ten EIC dollars reach households in the bottom two-fifths of New York City income earners.

Households claiming the New York City credit see their income lifted by an average of approximately 1.5 percent. The effect is most significant for those with lower earnings: households in the bottom 20 percent receive a larger boost relative to their incomes, an average increase of nearly 3 percent, according to ITEP estimates.

In addition to improving the economic standing of lower-income families, the New York City EIC reduces disparities by race and ethnicity, our estimates show. The credit supports workers and families of all races and ethnicities. But it plays an especially important role for Hispanic and Black households, according to ITEP estimates. We find that approximately one in five Hispanic households who file income taxes in New York City claim the EIC, and approximately one in six Black households receive the credit. In comparison, about one in seven tax filers overall claim the EIC, including approximately one in 14 white households.[5] By delivering a boost to greater proportions of Hispanic and Black households, the EIC helps to counteract racial barriers to genuine opportunity and economic security in New York City, promoting a more inclusive economy for all.[73]

New York City households claim the local credit on top of New York’s state Earned Income Credit, which matches 30 percent of the federal credit. A New York City resident who claims the state and city EICs can receive a combined boost worth up to 60 percent of the federal credit, the fourth largest EITC match available in the country.[74] For a single parent with two children, this means state and local credits of up to nearly $3,500 on top of the federal EITC. A single worker with no children can receive state and local credits worth up to $330 on top of the federal credit. The New York City and state EICs are not available to immigrant families and others filing taxes using Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers.[75],[76] Both credits follow the federal EITC’s rules for eligibility based on age.[77]

Claiming the New York City EIC

New York City households claim the EIC during the annual tax filing process. The credit is incorporated into the steps residents follow to file city income tax returns, with additional forms detailing instructions on claiming.[78] The city income tax filing process is administered by New York state, allowing residents to claim the local and state credits at the same time. As a result, the city and state EICs achieve similar levels of participation among New York City residents.[79]

Starting in 2022, the match on the federal EITC that a household receives depends on the household’s adjusted gross income. Households with incomes below $5,000 receive a 30 percent match to the federal credit, and those with incomes above $42,500 receive a 10 percent match. Households with income in between receive a scaled percentage match between 10 and 30 percent. The credit is applied to reduce any city income taxes owed. If income tax liability is smaller than the amount of the credit, the remaining amount is delivered directly to the household as a cash refund.[6]

The NYC EIC is highlighted in local efforts aiming to expand awareness and increase participation in local, state, and federal EITCs and other refundable credits supporting lower-income households. For example, following expansion of the credit in 2022, city policymakers invested in a $1.5 million multimedia outreach campaign to raise awareness and encourage participation in the EIC and other credits.[80] New York City also leverages partnerships and other coordination strategies to facilitate access to these credits. In partnership with the IRS, the city works to identify residents who are likely eligible for the city, state, and federal EITCs but have not yet claimed them. The city and the agency initiate outreach to these households and follow up with pre-filled amended tax forms that can be filed to claim the credits.[81] The city has also used innovative approaches like establishing free tax preparation services at hospitals and outpatient clinics.[82]

Background and History

The New York City EIC was established in 2004 and has boosted the incomes of workers and families ever since. City lawmakers introduced the credit as a refundable 5 percent match on residents’ federal EITC.[83],[84] This 5 percent credit remained in place until a 2022 reform expanded the credit to its current structure.

In the time between the credit’s introduction and its 2022 expansion, several policy leaders and advocates developed proposals to strengthen the credit. Beginning in 2005, for example, the city council speaker proposed doubling the credit to 10 percent of the federal EITC.[85] In 2016, the city comptroller released an analysis advocating for tripling the city EITC to 15 percent of the federal credit, showing that such an expansion would lift an added 15,000 households out of poverty.[86] And in 2021, New York City Mayor Eric Adams, then serving as Brooklyn borough president, proposed increasing the credit to 60 percent of the federal EITC for those earning under $30,000 and 30 percent for those earning more.[87]

City lawmakers secured a substantial overhaul of the New York City EIC in 2022.[88] With the expansion providing between 10 and 30 percent on top of the federal EITC, the credit now delivers an estimated additional $250 million directly into the pockets of New York City households each year.[89] The expansion is expected to result in a nearly five-fold increase in the average credit claimed per household, raising it to approximately $500.[90] The expansion provides a boost to all workers and families participating in the New York City EIC, with the largest share going to the 20 percent of lowest-income residents, according to our estimates.

“[The NYC EIC] is extra money in [families’] pockets during a very difficult time. That’s money to help pay for food, bills, rent, all of the things that New Yorkers know and deserve to receive. The EITC is a lifeline for far too many. And by allowing this increase, we are extending that lifetime.”

– Mayor Eric Adams remarking on the expanded NYC EIC in 2022

In addition to the NYC EIC, New York City has also piloted a program expanding the EITC for workers without children in the home, including people who do not have children and those who are noncustodial parents. The New York City Paycheck Plus credit, operational from 2015 to 2017, provided an enhanced EITC up to $2,000 per year to a targeted group of participants. The trial was funded by the New York City Center for Economic Opportunity and the Robin Hood Foundation and managed by the research organization MDRC.[91] Providing the additional cash credit to these low-income workers helped reduce severe poverty and increase earnings from employment, an analysis found.[92] A similar program was piloted in Atlanta from 2016 to 2019.[93]

Working Families Credit | San Francisco, California

How It Works

The Working Families Credit (WFC) is an EITC supplement provided by the city and county of San Francisco. In place since 2004, the program offers a $250 per-household annual payment to families with children at home who claim the federal or California EITC.[7] In 2021 the program reached just over 3,400 families, delivering around $850,000 to low-income residents.

The WFC adds a $250 boost on top of families’ federal or state EITC. The credit’s value does not depend on family size. The program builds on the income targeting of the EITC, focusing support on low-earning households. But while the federal EITC phases in benefits by 35 to 45 cents for each dollar earned, the WFC provides $250 to all families with at least some earnings, no matter how low. This flat structure provides predictable support to working families with very low incomes.

San Francisco does not levy a personal income tax, unlike New York City and Montgomery County but like four-fifths of U.S. localities.[94] Rather than offsetting a local income tax, San Francisco’s WFC acts as a direct cash boost to low-income residents, helping to alleviate unbalanced effects from sales, property, and other taxes levied by the city.

The credit is available to citizens as well as immigrant families who file taxes using Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers. The latter are eligible for the Working Families Credit if they have claimed the California EITC. The state credit is structured similarly to the federal EITC but more narrowly targeted to low-income households.[95]

Claiming the Credit

Families claim the WFC by submitting a form to the San Francisco Human Services Agency, attaching a copy of a current federal or state tax return documenting that the filer has at least one child and qualifies for the federal EITC, or, if filing with an ITIN, the CalEITC.[96] The application is available in several languages. Families apply around tax time, and credits are delivered beginning in May of each year following the close of the tax filing period. In 2020, approximately two in three WFC applications came from families filing with paid tax preparers, approximately 10 percent came from volunteer tax preparation sites, and approximately 20 percent came from people applying for the credit independently.[97]

Families typically apply soon after completing the federal and state tax process, and some tax preparation services offer assistance. San Francisco employees conduct year-round outreach to communities, tax preparers, and public support program enrollees to raise awareness and encourage residents to apply. Personnel also help connect WFC recipients with additional public supports they may be eligible for but not yet enrolled in such as health coverage, nutrition assistance, discounted transit access, utility bill relief, and free tax preparation.[98],[99]

Background and History

San Francisco leaders started the WFC in 2004 as a pilot program offering a 10 percent match on top of San Francisco families’ federal EITC.[100],[101] The program was made permanent two years later.[102] It has undergone modifications in years since, with reforms both expanding and reducing the credit’s size and eligibility over time.

When the credit was enacted permanently, it was restructured as a flat $100 per-household credit.[103] The 2006 enactment also shifted administration of the program from the San Francisco Treasurer and Tax Collector’s Office to the Human Services Agency. San Francisco established partnerships with volunteer and paid tax preparation services to facilitate access, and this coordination continues today.[104]

Beginning in 2010 policymakers narrowed WFC eligibility to only first-time recipients. This reform, enacted in response to a reduction in funding available for the credit, magnified the program’s focus on providing a local incentive for residents to begin claiming the federal EITC.[105] Program participation narrowed as a result, decreasing from approximately 11,000 households in 2009 to just under 3,000 in 2010.

San Francisco policymakers raised the supplement to $250 per household beginning in 2011. Households could receive the $250 credit by providing the Human Services Agency with bank information for direct deposit, a move to incentivize use of formal banking services.[106] Those not providing direct deposit information received a $100 paper check with the opportunity to claim the remaining $150 by providing bank information later. This structure remains in place today, with approximately 99 percent of filers opting for direct deposit.[107]

The WFC was temporarily raised to $500 per household for 2018, with households claiming a paper check receiving $200. The following year policymakers removed the WFC’s once-in-a-lifetime limit, restoring eligibility to all San Francisco families claiming the federal EITC. With eligibility expanded, participation in the WFC grew to approximately 3,700 families, the highest number of households to claim the credit since 2009 but below the 37,000 households claiming the federal EITC in San Francisco.[108]

In 2021 San Francisco delivered an additional one-time rapid cash payment of $250 to all families who received the credit the previous year, providing added support to residents likely to be experiencing financial stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Announcing the 2021 supplement, local officials emphasized that the pre-existing administrative infrastructure of the WFC enabled the city to reach low-income families quickly and efficiently amid economic turbulence. “Our city is unique in offering a Working Families Credit so we can provide additional financial support on top of the state and federal tax credits,” said Trent Rhorer, Executive Director of the San Francisco Human Services Agency. “Extending this local stimulus to more families provides emergency relief for those struggling to make ends meet at a critical moment in the pandemic economic slowdown.”[109]

The WFC has earned renewed attention in recent years, including some proposals for enhancement and expansion. In 2022, the San Francisco Guaranteed Income Advisory Group, a working group established by city leaders to advise on direct cash policies, highlighted the WFC’s potential as a scalable and sustainable tool for delivering financial support to low-income residents and asked city policymakers to consider strengthening the program’s benefits, reach, and administration.[110]

“We already have enough evidence that providing cash directly to poor households can be transformative; now is the time to pursue policy reforms and more radical strategies that can both scale up and sustain this seemingly simple approach. … San Francisco can scale up cash transfers locally by using the existing Working Families Credit.”

– San Francisco Guaranteed Income Advisory Group

The working group advised policymakers to consider increasing the credit’s dollar amount from its current $250 level or transitioning to a fully refundable local child tax credit. The group also proposed the city partner with California’s tax agency to automatically identify and deliver WFC payments to San Francisco families receiving the CalEITC, an administrative approach similar to Montgomery County’s, which has achieved a high local EITC participation rate.

Local EITC Pilots and Proposals

Chicago

Chicago piloted a temporary local EITC with a select group of residents in 2014. Participating residents received a portion of their federal EITC in four installments throughout the year, rather than receiving the full amount at tax time.[111] The payments helped families better meet real-time needs, benefitting their financial and social well-being, subsequent studies found.[112],[113],[114]

In 2019, ITEP assessed the potential impact of a permanent Chicago EITC. Enacting a city EITC matching 10 percent of the federal credit would boost residents’ incomes by $83 million, with over half that going to households in the lowest 20 percent of the income scale, we found.[115] ITEP identified the potential to unlock even stronger benefits by analyzing additional proposals outlined by the Chicago Resilient Families Initiative Task Force, an advisory group convened by the mayor and city council.[116]

“EITCs can be particularly helpful in cities because their tax systems rely heavily on excise taxes, property taxes, and in most cases sales taxes. Because of this reliance, low- and moderate-income families in these states pay a higher share of their income in taxes than wealthier families.

Given the significant gaps between incomes and cost of living, it behooves Chicago to consider instituting an Earned Income Tax Credit alongside any new broad-based revenue generation initiatives in the coming years.”

– Chicago Resilient Families Initiative Task Force

Matching 25 percent of the federal EITC while providing a robust minimum credit of $800 and expanding eligibility to full-time family caregivers, for instance, would lift Chicagoans’ incomes by $224 million with seven-tenths of the gain flowing to the bottom 20 percent, we found. These results highlight the opportunity to enact local EITCs that build on the federal credit while improving it to better meet the needs of families most in need of support.

Denver

Denver offered residents a refundable local credit matching 20 percent of residents’ federal EITC in 2002 and 2003, an amount worth up to about $800 a year for a parent of two and $500 for families with one child. In the view of local leaders, the credit provided a means to deliver targeted income support into the hands of low-paid working families with as few administrative hurdles or strings attached as possible.[117],[118]

The city-county established the pilot program with $5 million in annual funding from its allocation of federal block grant dollars. Families could receive the credit if they had one or more children and claimed the federal EITC in the prior year. In the program’s first year, 15 percent of Denver’s federal EITC filers applied to receive the local credit.[119] The credit was extended into 2003 but was not renewed the following year amid competing priorities in Denver’s budget.[120],[121]

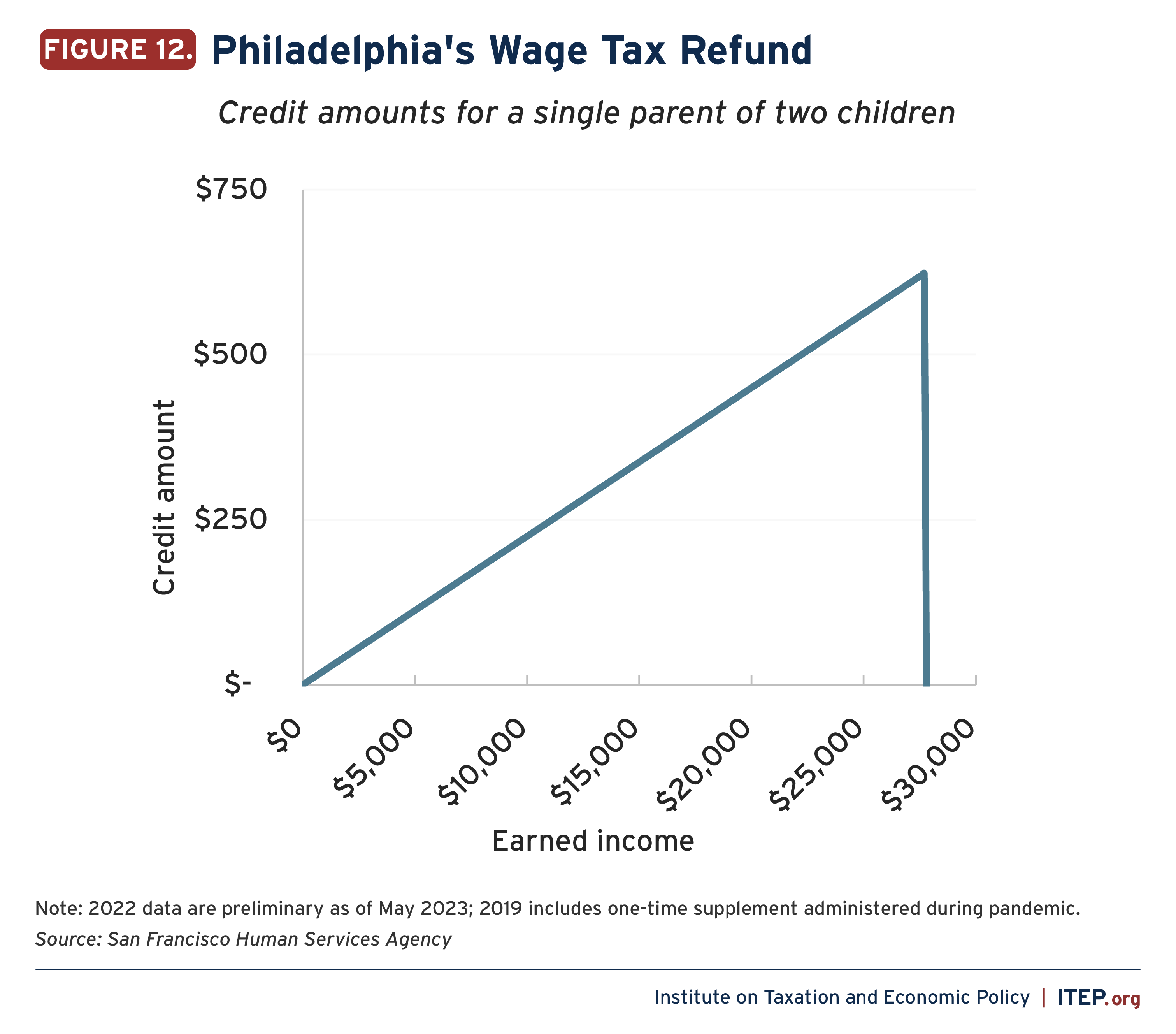

Wage Tax Refund | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Nonrefundable credit

While not formally an EITC, the income-based Wage Tax Refund in Philadelphia bears similarity to the program. The Wage Tax Refund is a nonrefundable credit that reduces Philadelphia’s city income tax by 60 percent for eligible low-income residents. Approximately 1,500 people claimed the Wage Tax Refund in 2021.[122] Around 60,000 are estimated to be eligible for the credit.[123]

Philadelphia income taxes are withheld from paychecks throughout the year at a 3.75 percent tax rate, starting with the first dollar earned. Low-income filers eligible for the Wage Tax Refund can apply to the city at tax time using a paper form or online portal to receive three-fifths of this amount refunded back, retroactively reducing the income tax rate to 1.5 percent.[124],[8]

To claim the Philadelphia credit, a tax filer must first claim a similar nonrefundable state income tax credit, Schedule SP. Schedule SP and the Wage Tax Refund target relief to low-income households with an income eligibility cutoff that rises according to the number of children claimed.[125] A person with no dependent children is eligible if her income is below $18,250; for a person with one child, the income limit is $27,750; for a person with two children, it is $37,250. In comparison, the phase-out points for the EITC are $17,640, $46,560, and $52,918, respectively.[126]

Philadelphia policymakers and advocates have sought to improve the Wage Tax Refund in recent years by increasing its size and enhancing outreach and participation.[127],[128]

Example | A parent of two children earning $25,000 has $938 in Philadelphia income tax withheld over the year by her employer. She applies for the Wage Tax Refund and receives three-fifths of this amount, $563, refunded back from the city. Her remaining city income tax liability is $375.

Footnotes

[1] Years noted in this report generally refer to tax years, rather than calendar years or fiscal years. Tax years correspond to the year income is earned, which is the year prior to when taxes on that income are filed and tax refunds are received. Policy changes described in this report were frequently made in one calendar year and applied retroactively to the prior tax year.

[2] The credit was enacted in 1999, with residents able to claim refunds based on tax year 1998.

[3] See methodology for more information on ITEP’s Tax Microsimulation Model and sources of income included in modeling analyses.

[4] Certain low-income tax filers in Maryland are eligible for a second local nonrefundable credit, the poverty level credit, if their local income tax is not fully offset by the EITC. To be eligible for the poverty level credit, a tax filer must have income below the federal poverty level. It offers a credit against local income tax equal to up to 0.16% of a filer’s income. In tax year 2018, 19,000 tax filers statewide claimed the local poverty level credit, receiving $120 on average.

[5] See methodology for more information on ITEP’s Tax Microsimulation Model and its approach to estimating effects by race and ethnicity.

[6] Certain New York City residents with low incomes are also eligible to claim the city’s refundable child and dependent care credit and nonrefundable household credit. The child and dependent care credit reached approximately 3,000 households in 2021, providing around $260 on average. The household credit reached approximately 320,000 households in 2019, providing $24 on average.

[7] The credit was enacted in 2005, with residents able to claim based on tax year 2004.

[8] Nonresidents earning income in Philadelphia have tax withheld at a 3.44 percent rate and can also file to claim the Income-Based Wage Tax Refund.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for their generous support of this project. We extend gratitude to the numerous policymakers, analysts, and advocates who shared their knowledge and expertise during the development of this report. A special thanks to Michael Dean, Christine D’Onfrio, Anne Hill, Jennifer March, Robin McKinney, Tonaeya Moore, Lonia Muckle, Pete Nabozny, Graham O’Neill, Kali Schumitz, and Peri Weisberg.

We also thank our ITEP colleagues, particularly Aidan Davis, Carl Davis, Amy Hanauer, Spandan Marasini, Alex Welch, and Jon Whiten for their contributions to this report.

Methodology

To analyze impacts across the income distribution of EITC policies in New York City and Montgomery County, we use the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model. To model policy impacts at the local level, ITEP assigns each observation in our Microsimulation model a probability weight of living within a specific locality. These probability weights are calculated through a match with the American Community Survey.

American Community Survey individual and household level data are broken down into tax units, and then a crosswalk between the 5-year sample and our microsimulation model is produced, using several characteristics present in both data sets. These include income, marital status, homeownership, age, and number and age of children. For the purposes of ITEP’s model, income for each tax unit includes wage and salary earnings, retirement income, child support, unemployment compensation, worker’s compensation, and other income from public supports and financial assistance.

The geographic boundaries of each locality are determined by aggregating Public Use Microdata Areas – the smallest geography available within the American Community Survey microdata – to best match each local tax jurisdiction. The resulting estimates are then checked against published data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Internal Revenue Service, and state revenue departments to ensure that they accurately reflect the income and demographic profile of the locality.

Constraints in available data prevent us from providing analysis of impacts across race and ethnicity from the local credits in Montgomery County and San Francisco, impacts across the income distribution in San Francisco, and impacts for certain races and ethnicities at this time.

For additional information about the ITEP Microsimulation Tax Model, visit itep.org/itep-tax-model.

Endnotes

[1] Economic Opportunity, Poverty & Well-Being, Boston University Initiative on Cities, 2022. https://www.bu.edu/ioc/2023/04/04/2022-menino-survey-economic-opportunity-poverty-well-being/

[2] Internal Revenue Service Statistics for Tax Returns with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-the-earned-income

[3] Aidan Davis and Neva Butkus, Boosting Incomes, Improving Equity: State Earned Income Tax Credits in 2023, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2023. https://itep.org/boosting-incomes-improving-equity-state-earned-income-tax-credits-in-2023/

[4] Hilary Hoynes, “The Earned Income Tax Credit,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, November 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002716219881621

[5] Brian Hill and Tami Gurley-Calvez, “Earned Income Tax Credits and Infant Health: A Local EITC Investigation,” National Tax Journal 72 (3) 617-646, September 2019. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/ntjjournl/v_3a72_3ay_3a2019_3ai_3a3_3ap_3a617-646.htm

[6] Jeannette Wicks-Lim and Peter S. Arno, Improving population health by reducing poverty: New York’s Earned Income Tax Credit, SSM Population Health, March 2017. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29349231/

[7] David Simon, Mark McInerney, and Sarah Goodell, The Earned Income Tax Credit, Poverty, and Health, Health Affairs, October 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.769687/

[8] Hilary Hoynes, Doug Miller, and David Simon, “Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy Vol. 7 No. 1, February 2015. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20120179

[9] Paola Scommegna, “Anti-Poverty Tax Credits Linked to Declines in Reports of Child Neglect, Youth Violence, and Juvenile Convictions,” Population Reference Bureau, December 2022. https://www.prb.org/resources/anti-poverty-tax-credits-linked-to-declines-in-reports-of-child-neglect-youth-violence-and-juvenile-convictions/

[10] Julie-Anne Cronin, Portia DeFilippes, and Robin Fisher, “Tax Expenditures by Race and Hispanic Ethnicity: An Application of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Race and Hispanic Ethnicity Imputation,” U.S. Treasury Department Office of Tax Analysis, January 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/WP-122.pdf

[11] Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity: 2017 Tax Law Took Step Backward,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-the-federal-tax-code-can-better-advance-racial-equity

[12] K. Steven Brown, “Racial Inequality in the Labor Market and Employment Opportunities,” WorkRise Network, September 2020. https://www.workrisenetwork.org/publications/racial-inequality-labor-market-and-employment-opportunities

[13] Bradley Hardy, Charles Hokayem, and James P. Ziliak, “Income Inequality, Race, and the EITC,” National Tax Journal, March 2022. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/717959

[14] Who Pays: A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, October 2018. https://itep.org/whopays

[15] Carl Davis, “How State Tax Systems Worsen the Economic Divide – in Charts,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 2019. https://itep.org/how-state-tax-systems-worsen-the-economic-divide-in-charts/

[16] Maggie R. Jones and James P. Ziliak, “The Antipoverty Impact of the EITC: New Estimates from Survey and Administrative Tax Records,” National Tax Journal Vol. 75, Number 3, April 2019. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/720614

[17] Internal Revenue Service Statistics for Tax Returns with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-the-earned-income

[18] Neva Butkus, “Refundable Credits a Winning Policy Choice Again in 2023,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 2023. https://itep.org/refundable-credits-winning-policy-choice-2023-child-tax-credit-eitc/

[19] Andrew Greenlee, Karen Kramer, Flavia Andrade, Dylan Bellisle, Renee Blanks, and Ruby Mendenhall, “Financial Instability in the Earned Income Tax Credit Program: Can Advanced Periodic Payments Ameliorate Systemic Stressors?” Urban Affairs Review Volume 57, Issue 6, November 2021. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1078087420921527?journalCode=uarb

[20] The City and County of Denver, Colorado, “First-Ever City-Sponsored Earned Income Tax Credit,” January 2002. https://web.archive.org/web/20020807000343/http://www.denvergov.org/newsarticle.asp?id=3647

[21] Robert Rehrmann, Matthew Bennett, Benjamin Blank, George Butler, Jr., Mya Dempsey, Mindy McConville, Maureen Merzlak, Heather Ruby, et al., “Evaluation of the Maryland Earned Income Tax Credit: Poverty in Maryland and the Earned Income Tax Credit,” Maryland Department of Legislative Services Office of Policy Analysis. September 2015. https://dls.maryland.gov/pubs/prod/TaxFiscalPlan/Evaluation-of-the-Maryland-Earned-Income-Tax-Credit.pdf

[22] City of Philadelphia Department of Revenue, Income-based Wage Tax Refund Petition Tax Year 2022 – Residents only. https://www.phila.gov/media/20230206101743/Residents-income-based-Wage-Tax-refund-2022.pdf

[23] Andrew Boardman and Galen Hendricks, “How Local Governments Raise Revenue—and What it Means for Tax Equity,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, March 2023. https://itep.org/how-local-governments-raise-revenue-effects-on-tax-equity/

[24] Internal Revenue Service, “About Publication 596, Earned Income Credit.” https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-596

[25] Internal Revenue Service, “Frequently Asked Questions / Childcare Credit, Other Credits / Child Tax Credit 4.” https://www.irs.gov/faqs/childcare-credit-other-credits/child-tax-credit/child-tax-credit-4

[26] Aidan Davis and Neva Butkus, Boosting Incomes, Improving Equity: State Earned Income Tax Credits in 2023, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2023. https://itep.org/boosting-incomes-improving-equity-state-earned-income-tax-credits-in-2023/

[27] Internal Revenue Code, § 32(c)(1)(A)(ii)(II). https://uscode.house.gov/browse/prelim@title26/subtitleA/chapter1/subchapterA/part4/subpartC&edition=prelim

[28] Aidan Davis, Expanding State EITCs: Age Enhancements and a Credit Increase for Workers without Children in the Home,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, February 2020. https://itep.org/expanding-state-eitcs-age-enhancements/

[29] Montgomery County, Maryland, “Council approves Working Families Income Supplement Bill to expand eligibility for the tax credit,” June 2021. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/MDMONTGOMERY/bulletins/2e3edb9

[30] Aidan Davis and Neva Butkus, Boosting Incomes, Improving Equity: State Earned Income Tax Credits in 2023, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2023. https://itep.org/boosting-incomes-improving-equity-state-earned-income-tax-credits-in-2023/

[31] Internal Revenue Service, “EITC Participation Rate by States Tax Years 2012 through 2019.” https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/participation-rate-by-state/eitc-participation-rate-by-states

[32] Essie McGuire and Tara Clemons Johnson, Montgomery County Government Operations and Fiscal Policy Committee Memorandum: Worksession – FY24 Operating Budget, Working Families Income. Supplement Non-Departmental Account, April 2023. https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/council/Resources/Files/agenda/cm/2023/20230427/20230427_GO1.pdf

[33] Los Angeles Office of the City Clerk, “Status Report – Improving Receipt of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in Los Angeles,” October 2010. https://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2009/09-2750_RPT_CLA_10-25-10.pdf

[34] Internal Revenue Service, “IRS takes additional steps to protect taxpayer data; plans to end faxing and third-party mailings of certain tax transcripts,” June 2019. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-takes-additional-steps-to-protect-taxpayer-data-plans-to-end-faxing-and-third-party-mailings-of-certain-tax-transcripts

[35] Internal Revenue Service, “Special Outreach Project with New York City’s Department of Finance,” March 2023. https://www.eitc.irs.gov/partner-toolkit/special-outreach-project-with-new-york-citys-department-of-finance/special-outreach

[36]Testimony of Sam Miller, Assistant Commissioner of the New York City Department of Finance On the Earned Income Tax Credit Mailing Project, Business Development Committee Los Angeles City Council, November 2009. https://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2009/09-2750_misc_11-17-09.pdf

[37] “Mayor Adams Launches Marketing Campaign Promoting Enhanced Earned Income Tax Benefits Available to Eligible New Yorkers This Tax Season,” March 2023. https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/146-23/mayor-adams-launches-marketing-campaign-promoting-enhanced-earned-income-tax-benefits-available-to#/0

[38] Montgomery County Government, Cashback Home. https://montgomerycountymd.gov/cashback/

[39] Allison Prang, “Reaching the unbanked: Lessons from a San Francisco experiment,” American Banker, June 2017. https://www.americanbanker.com/news/reaching-the-unbanked-lessons-learned-from-a-san-francisco-experiment

[40] Leigh Phillips and Anne Stuhldreher, “Building Better Bank Ons: Top 10 Lessons from Bank On San Francisco,” New America Foundation, February 2011. https://static.newamerica.org/attachments/3752-building-better-bank-ons/PhillipsStuhldreherBankOn2-11.71f3e6447a8d486c998a171835b5f11d.pdf

[41] David Neumark and Katherine Williams, “Do State Earned Income Tax Credits Increase Participation in the Federal EITC?,” Public Finance Review, September 2020. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1091142120945336

[42] ITEP estimate based on data from the Maryland Office of the Comptroller and the Montgomery County Council.

[43] Aidan Davis and Neva Butkus, “Boosting Incomes, Improving Equity: State Earned Income Tax Credits in 2023,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2023. https://itep.org/boosting-incomes-improving-equity-state-earned-income-tax-credits-in-2023/

[44] Meg Wiehe and Misha Hill, “State & Local Tax Contributions of Young Undocumented Immigrants,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2018. https://itep.org/state-local-tax-contributions-of-young-undocumented-immigrants/#.WQiJuYgrKUl

[45] Capital Area Food Bank, “Snapshot of 2023 Policy Agenda by Jurisdiction,” January 2021. https://www.capitalareafoodbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CAFB_PolicyAgenda2023_ByJurisdiction_Final.pdf

[46] Shepard Nevel, “The Local Path To Making Work Pay: Denver’s Earned Income Credit Experience,” The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, March 2002. https://web.archive.org/web/20060110181143/https://www.brookings.edu/dybdocroot/es/urban/innovations/welfessay1.htm

[47] Comptroller of Maryland, Maryland Income Tax Rates and Brackets. https://www.marylandtaxes.gov/individual/income/tax-info/tax-rates.php

[48] Earned income tax credit, Maryland Revised Statutes, Tax – General § 10-704. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Laws/StatuteText?article=gtg§ion=10-704&enactments=false

[49] Patrick Herron, “County Executive Elrich Encourages Residents to ‘Get All Your Tax Credits’.” The MoCo Show. January 2022. https://mocoshow.com/blog/county-executive-elrich-encourages-residents-to-get-all-your-tax-credits/

[50] Ibid.

[51] Robert Rehrmann, Matthew Bennett, Benjamin Blank, George Butler, Jr., Mya Dempsey, Mindy McConville, Maureen Merzlak, Heather Ruby, et al., “Evaluation of the Maryland Earned Income Tax Credit: Poverty in Maryland and the Earned Income Tax Credit,” Maryland Department of Legislative Services Office of Policy Analysis. September 2015. https://dls.maryland.gov/pubs/prod/TaxFiscalPlan/Evaluation-of-the-Maryland-Earned-Income-Tax-Credit.pdf

[52] Family Prosperity Act of 2023, Maryland SB 552/CF HB 547 (2023). https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/SB0552?ys=2023rs

[53] Tax Reform Act of 2007, Maryland SB 2 Chapter 3 (2007). https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2007s1/chapters_noln/Ch_3_sb0002E.pdf

[54] Working Families Income Supplement, Montgomery County Article XIV. https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/montgomerycounty/latest/montgomeryco_md/0-0-0-129726

[55] Concerning: Working Families Income Supplement – Amount, Laws of Montgomery County 2013 Law Ch. 31, Montgomery County Council. https://apps.montgomerycountymd.gov/ccllims/DownloadFilePage?FileName=859_1_2517_Bill_8-13_Signed_20140701.pdf

[56] Ibid.

[57] “Montgomery County Poised to Expand Its Exemplary EITC,” Citizens for Tax Justice, August 2013. https://ctj.org/montgomery-county-poised-to-expand-its-exemplary-eitc/

[58] Family Prosperity Act of 2023, Maryland SB 552/CF HB 547 (2023). https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/HB0547

[59] Essie McGuire and Tara Clemons Johnson, Montgomery County Government Operations and Fiscal Policy Committee Memorandum: Worksession – FY24 Operating Budget, Working Families Income Supplement Non-Departmental Account. April 2023. https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/council/Resources/Files/agenda/cm/2023/20230427/20230427_GO1.pdf

[60] Adam Pagnucco, “Hucker: MoCo Will Expand its EITC,” Montgomery Perspective, February 2021. https://montgomeryperspective.com/2021/02/16/hucker-moco-will-expand-its-eitc/

[61] Aidan Davis, “Boosting Incomes and Improving Tax Equity with State Earned Income Tax Credits in 2022,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 2022. https://itep.org/boosting-incomes-and-improving-tax-equity-with-state-earned-income-tax-credits-2022/

[62] Montgomery County, Maryland. (2021, June 15). Council approves Working Families Income Supplement Bill to expand eligibility for the tax credit [Press Release]. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/MDMONTGOMERY/bulletins/2e3edb9

[63] Gene Smith to Montgomery County Government Operations and Fiscal Policy (GO) Committee, Memorandum: FY23 Operating Budget: Certain Non-Departmental Accounts (NDA). April 2022. https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/council/Resources/Files/agenda/cm/2022/20220502/20220502_GO4-10.pdf

[64] Ibid.

[65] Montgomery County Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2024 Recommended Operating Budget in Brief, March 2023. https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/OMB/Resources/Files/omb/pdfs/fy24/psprec/FY24_BudgetinBrief.pdf

[66] Robert Rehrmann, Matthew Bennett, Benjamin Blank, George Butler, Jr., Mya Dempsey, Mindy McConville, Maureen Merzlak, Heather Ruby, et al., “Evaluation of the Maryland Earned Income Tax Credit: Poverty in Maryland and the Earned Income Tax Credit,” Maryland Department of Legislative Services Office of Policy Analysis. September 2015. https://dls.maryland.gov/pubs/prod/TaxFiscalPlan/Evaluation-of-the-Maryland-Earned-Income-Tax-Credit.pdf

[67] Maryland House Bill 1149 of the 1999 Regular Session. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/1999rs/bills/hb/hb1149e.PDF

[68] Comptroller of Maryland, Personal Income Tax Statistics of Income, Tax Year 2018. https://www.marylandtaxes.gov/reports/static-files/revenue/statisticsofincome/individual/2018_Personal_SOI.pdf

[69] Earned income tax credit, Maryland Revised Statutes, Tax – General § 10-704. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Laws/StatuteText?article=gtg§ion=10-704&enactments=false

[70] New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, Earned income credit (New York State), Accessed August 2023. https://www.tax.ny.gov/pit/credits/earned_income_credit.htm